Features

On education and schools

by Usvatte-aratchi

Two thoughtful short essays on schools and education appeared in The Island newspaper on January 20th and 21st. The first was written by Lokubandara Tillakaratne, and the second by Mahendran Thiruvarangan of the Department of Linguistics and English at the University of Jaffna. Both urged reforms in the systems in Sri Lanka. Thiruvarangan’s essay was more abstract and global in perspective. Tillekartane examined the structure of schools in Sri Lanka.

Thiruvarangan explicitly set out to examine the relationship between ‘school leavers and the job market’; he proceeded to observe this relationship from a global perspective; obiter dicta, he emphasized the value of ‘the humanities and social sciences’ in university education to enable, among other things, students to resist the hegemonies of global capitalism’. Neither of them had any numbers in their essays. Neither referred to the systematic empirical information on these subjects, which is widely available.

I will first deal with Tiruvaragan’s essay. He started with observations about ‘… the global south and its working classes (who) are pushed to experiencing extreme forms of vulnerability’. That assertion is worth examining in light of developments in the last 30 years or so, especially in this part of the world. We have seen a spectacular rise in living conditions of more than a billion in one short generation in China and India.

A generation before that, a large swath of people in Japan, Korea, Taiwan (China), and Malaysia emerged from poverty and are now among the affluent. Consequently, that part of Asia now contains the second (Japan), third (China) and fourth (India) leading economies in the world and contain about 45% of the world’s population. Indonesia may be hard by their heels. In Africa, Ivory Coast, Ethiopia, Rwanda and some others have done well during the last 30 years or so.

Those goals were all achieved by joining ‘the globalized labour force for the (mostly) private sector’. The lives of those who rose from poverty have been made less vulnerable as one can see in the changes in the consumption goods baskets of these people. They all have begun to consume more protein. Sri Lanka was a striking exception that failed to participate in that spate of rapid economic growth during the last 50 years and more. Our entrepreneurs failed to join the world supply chains in the burgeoning production of and trade in electronic goods. An infatuation with the imagined greatness of our past consumed government policies, forgetting that we live in the present and will live in the future; it is sheer vanity to search for lost time.

Thiruvarangan supports the claim for teaching and research in the humanities and the social sciences. This is a part of a larger debate spread among academics and others in most parts of the world. The relationship between universities and the economy and society was rapidly transformed in the latter half of the 19th century. From an institution that the church dominated, universities became partners in innovations in the economy and in the formation of economic and social policies. Germany led the way. In the words of the official historian of Cambridge University, it changed ‘… from a provincial seminary (in 1870) to … (a university) teaching disciplines almost past counting and of high international fame in many of them.’ There were five clusters of great inventions in the second half of the 19th century that transformed people’s lives, wherever, forever.

The first was electricity and the electric motor; the second, the internal combustion engine; the third., petroleum and natural gas and the production of plastics; (In early 20th century, Sir Wiiliam Hardy, who made important contributions in both chemistry and physics, advised young Joseph Needham that the future lay in ‘atoms and molecules, atoms and molecules, my boy’.); the fourth, in entertainment and communications and the last in running water, indoor plumbing and urban sanitation structures. These inventions which contributed to the marked continued rise in living standards worldwide (A few years ago, Prime Minister Modi announced to the General Assembly of the United Nations that his government had built 112 million toilets in his country) did not come from universities but were the output inspired skilled craftsmen.

During the period 1850 to 1900, teaching and research in natural and social sciences became common, in Germany, the US and the UK. In Cambridge, the Natural Sciences Tripos was established in 1851 and the Mechanical Tripos in 1894. The Economics Tripos examination was first held in 1905 with 10 students. Meanwhile, universities came into people’s lives more forcefully. Across the Atlantic, the Merrill Acts of 1862 and 1864 had started Land Grant Colleges in individual states. John Bascom, President of Wisconsin University, pledged, in1887, that (the university) would contribute to the work of social advancement by encouraging a more organic connection between its activities and community needs.

In 1892 Richard T. Ely (who founded the American Economic Review) started the School of Economics, Political Science and History making the university more of a ‘service station’ for the society it served. Way off in the North Pacific, the Imperial University of Japan was opened in Tokyo in 1887. Over the years, it has been a major institution in Japan’s economic and social development. These links between the university and the economy and society grew far closer, a hundred years later when universities became incubation chambers for new industries and enterprises. Universities began teaching politics (not simply the Plato-Aristotle variety) and government and business administration. As I remarked in the J. E. Jayasuriya Lecture in 2004, Sarasvati had met Lakshmi in universities. (This year, Professor Panduka Karunanayake of the Faculty of Medicine, Colombo will deliver the lecture on February 14 at the SLFI auditorium.)

That long harangue was to bring home the point that universities, industry, and society have drawn closely together because mathematics, natural sciences, economics, and social studies in universities have become integral to the working and development of modern societies. That connection is weak in those societies where the structure of the economy still does not need the services usually provided by universities to industry and services in rich countries. Once the need for school teachers is satisfied (as in Sri Lanka), the demand for university graduates in the humanities will fall and the demand for graduates in science and technology rise, when industries develop. Hence the voluble demand from School Development Officers to be appointed as teachers, in a situation where the student: teacher ratio is as low (good) as 18. Recently, the Arab countries (Arabia, Dubai, Qatar, Kuwait and Bahrain), flush with funds from the sale of plentiful petroleum at monopoly prices, opened some universities, all for science, technology and management. In general, universities have followed changes in economies and societies.

In as much as church and religion were integral parts of the lives of people in medieval societies, science and technology are integral parts of people’s lives in modern societies. One switches off a light and goes to bed at night and gets up to switch on a fan, to begin the day. The modern equivalents of liberal arts are mathematics and science. As economies and societies have changed, the demand for education in the traditional liberal arts has declined. One cannot live in the past.

Tillakaratne dealt with the structure of the school system in the country and found there ‘a neo-caste’ system. This is wholly misleading. I will not deal with ‘International Schools’ because they are neither international nor schools. They are business enterprises that sell educational services to local people with adequate purchasing power. Children of a few foreigners, temporarily resident in this country, also attend them. The students and teachers are overwhelmingly local, though they prepare students for examinations overseas. However, local schools in many countries prepare students for the International Baccalaureate (IB). In any case, I know little about them.

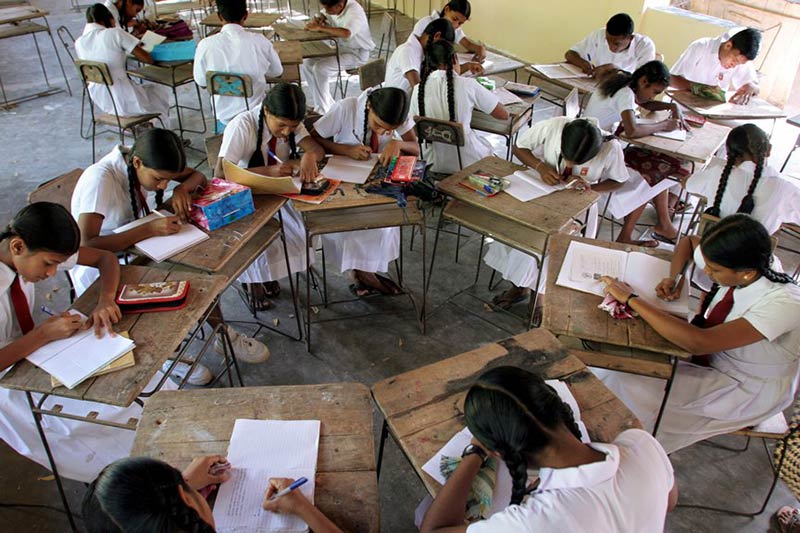

There are now 10,000 government schools in five categories depending upon the grades they teach and the subject areas they teach. The most numerous (7,200) are primary schools. 2,000 teach up to Grade 11 and the balance up to Grade 12 in the arts and/or science streams.

More than half of all schools enroll less than 200 pupils; 15% less than 50 and another 16% have less than 100. Of all schools, 400 are national schools, teaching 380,000 students. The student/teacher ratio is 15 students in Provincial Schools and 19 students in National Schools. The low student/teacher ratio in provincial schools is accounted for by the large number of small schools there. Nor is there a shortage of Graduate Trained teachers in them. There is a shortage of English, mathematics, science and technology teachers. There is a s shortage of competent English teachers overall. In an analysis of student’s performance in the GCE (O/L) examination, a few years ago, NIE showed that the proportion of students who received pass marks, and above, was 17 percent of all who sat for that paper. The real disadvantage that children in small schools suffer is that they have narrowly limited options. Small schools in their vicinity are necessary for small children to attend. It is economically infeasible to provide in small schools the multiplicity of options available in large schools. It is a hard nut to crack. Back in the 1940s, the solution was to open boarding schools in rural centres (e.g. Wanduramba, Matugama, Ibbagamuwa, Poramadulla). With the rapid growth in the school population that proved an unlikely solution. Poor transport facilities in rural areas make a feasible solution many years away.

With that rough sketch of the structure of schools, it is grossly misleading to label it as a ‘neo-caste’. A caste system, as we know, stratifies society. People belong in castes by ascription; they are born to it and there is no escape up; they can fall. When a Brahmin woman marries a Shudra man, their children are Shudra. That stratification lasts from generation to generation. In contrast, our school system consists of five steps, success at which paves for entry into the next higher. Does the term neo-caste take away the essential feature of a caste system? Tillakaratne’s contention that among schools there are differences of endowments is perfectly valid. Royal College, Colombo, is endowed differently from Royal College, Polonnaruva, or the Central School in Narammala. This is true of schools in all societies: in China, governed by the Communist Party, and in the US, governed by competing parties. In China, children of workers who migrate to cities must go to rural schools where their hukou is valid. More prosperous city dwellers are entitled to attend city schools superior to rural ones. This is true in the US, as well. Children of more educated and more wealthy parents live in culturally richer homes and, and no matter what school they attend, they outperform those from culturally poorer homes. Black children, who are the most culturally deprived population, perform worse than any other ethnic group in the US. Among us, so do families in plantations. When the two disadvantages combine, as often, when children from poor homes who go to poorly endowed schools, they suffer a disabling double whammy.

One of the major contributions educational policies made to this society is the rapid advancement of women. There are more girls than boys in government schools. More women than men go to university. More men opt to study engineering and related disciplines. That is a common feature in most societies, except in Eastern Europe (e.g. Hungary). In the civil service, there are more women than men. Women have occupied the highest seats of power in the country. This year, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and the Prime Minister are women- the head of the judiciary and the leader of the governing party in Parliament and of the Cabinet (primus inter pares); and those positions, they occupy, not as close relatives or acolytes of powerful men. The displacement from government in 2024 of a cautery of urban plutocrats some of whose principal sharpened talent was plundering the public purse (degree PPP) was the handiwork of a generation that had been educated in rural government schools. They are expected to change much in our society.

But for the education system chastised by Tillakaratne as a ‘neo-caste system’ millions of young men and women who during the last 75 years and more became university professors and vice-chancellors, civil servants, doctors, lawyers, school teachers and principals, businessmen and other professionals who otherwise would have been stuck in a genuine caste system. The education system is the alchemy that dissolved the rigidities of a caste system, that Tillakaratne mentioned. The education system is not responsible for the economic stagnation in this society which has limited opportunities for a burgeoning educated population.

Our school system has no features in common with a caste system. There are differences between the quality of schools in rich urban areas and poor rural areas. However, this is a feature in almost all societies. Those differences arise from large inequalities and inequities in the wide society which affect both the quality of schools and the culture in households. It is when access to education and wealth are closed to certain groups that an education system takes on the nature of a caste system. The school system in this country during the last 75 years has been a wide ladder on which, millions climbed onto a platform that remained too narrow to accommodate them. Those crowded out jumped onto platforms overseas.

Features

From disaster relief to system change

The impact of Cyclone Ditwah was asymmetric. The rains and floods affected the central hills more severely than other parts of the country. The rebuilding process is now proceeding likewise in an asymmetric manner in which the Malaiyaha Tamil community is being disadvantaged. Disasters may be triggered by nature, but their effects are shaped by politics, history and long-standing exclusions. The Malaiyaha Tamils who live and work on plantations entered this crisis already disadvantaged. Cyclone Ditwah has exposed the central problem that has been with this community for generations.

A fundamental principle of justice and fair play is to recognise that those who are situated differently need to be treated differently. Equal treatment may yield inequitable outcomes to those who are unequal. This is not a radical idea. It is a core principle of good governance, reflected in constitutional guarantees of equality and in international standards on non-discrimination and social justice. The government itself made this point very powerfully when it provided a subsidy of Rs 200 a day to plantation workers out of the government budget to do justice to workers who had been unable to get the increase they demanded from plantation companies for nearly ten years. The same logic applies with even greater force in the aftermath of Cyclone Ditwah.

A discussion last week hosted by the Centre for Policy Alternatives on relief and rebuilding after Cyclone Ditwah brought into sharp focus the major deprivation continually suffered by the Malaiyaha Tamils who are plantation workers. As descendants of indentured labourers brought from India by British colonial rulers over two centuries ago, plantation workers have been tied to plantations under dreadful conditions. Independence changed flags and constitutions, but it did not fundamentally change this relationship. The housing of plantation workers has not been significantly upgraded by either the government or plantation companies. Many families live in line rooms that were not designed for permanent habitation, let alone to withstand extreme weather events.

Unimplementable Promise

In the aftermath of the cyclone disaster, the government pledged to provide every family with relief measures, starting with Rs 25,000 to clean their houses and going up to Rs 5 million to rebuild them. Unfortunately, a large number of the affected Malaiyaha Tamil people have not received even the initial Rs 25,000. Malaiyaha Tamil plantation workers do not own the land on which they live or the houses they occupy. As a result, they are not eligible to receive the relief offered by the government to which other victims of the cyclone disaster are entitled. This is where a historical injustice turns into a present-day policy failure. What is presented as non-partisan governance can end up reproducing discrimination.

The problem extends beyond housing. Equal rules applied to unequal conditions yield unequal outcomes. Plantation workers cannot register their small businesses because the land on which they conduct their businesses is owned by plantation companies. As their businesses are not registered, they are not eligible for government compensation for loss of business. In addition, government communication largely takes place in the Sinhala language. Many families have no clear idea of the processes to be followed, the documents required or the timelines involved. Information asymmetry deepens powerlessness. It is in this context that Malaiyaha Tamil politicians express their feeling that what is happening is racism. The fact is that a community that contributes enormously to the national economy remains excluded from the benefits of citizenship.

What makes this exclusion particularly unjust is that it is entirely unnecessary. There is anything between 200,000-240,000 hectares available to plantation companies. If each Malaiyaha Tamil family is given ten perches, this would amount to approximately one and a half million perches for an estimated one hundred and fifty thousand families. This works out to about four thousand hectares only, or roughly two percent of available plantation land. By way of contrast, Sinhala villages that need to be relocated are promised twenty perches per family. So far, the Malaiyaha Tamils have been promised nothing.

Adequate Land

At the CPA discussion, it was pointed out that there is adequate land on plantations that can be allocated to the Malaiyaha Tamil community. In the recent past, plantation land has been allocated for different economic purposes, including tourism, renewable energy and other commercial ventures. Official assessments presented to Parliament have acknowledged that substantial areas of plantation land remain underutilised or unproductive, particularly in the tea sector where ageing bushes, labour shortages and declining profitability have constrained effective land use. The argument that there is no land is therefore unconvincing. The real issue is not availability but political will and policy clarity.

Granting land rights to plantation communities needs also to be done in a systematic manner, with proper planning and consultation, and with care taken to ensure that the economic viability of the plantation economy is not undermined. There is also a need to explain to the larger Sri Lankan community the special circumstances under which the Malaiyaha Tamils became one of the country’s poorest communities. But these are matters of design, not excuses for inaction. The plantation sector has already adapted to major changes in ownership, labour patterns and land use. A carefully structured programme of land allocation for housing would strengthen rather than weaken long term stability.

Out of one million Malaiyaha Tamils, it is estimated that only 100,000 to 150,000 of them currently work on plantations. This alone should challenge outdated assumptions that land rights for plantation communities would undermine the plantation economy. What has not changed is the legal and social framework that keeps workers landless and dependent. The destruction of housing is now so great that plantation companies are unlikely to rebuild. They claim to be losing money. In the past, they have largely sought to extract value from estates rather than invest in long term community development. This leaves the government with a clear responsibility. Disaster recovery cannot be outsourced to entities that disclaim responsibility when it becomes inconvenient in dealing with citizens of the country with the vote.

The NPP government was elected on a promise of system change. The principle of equal treatment demands that Malaiyaha Tamil plantation workers be vested with ownership of land for housing. Justice demands that this be done soon. In a context where many government programmes provide land to landless citizens across the country, providing land ownership to Malaiyaha Tamil families is good governance. Land ownership would allow plantation workers to register homes, businesses and cooperatives and would enable them to access credit, insurance and compensation which are rights of citizens guaranteed by the constitution. Most importantly, it would give them a stake that is not dependent on the goodwill of companies or the discretion of officials. The question now is whether the government will use this moment to rebuild houses and also a common citizenship that does not rupture again.

by Jehan Perera

Features

Securing public trust in public office: A Christian perspective

(This is an adapted version of the Bishop Cyril Abeynaike Memorial Lecture delivered on 14 June 2025 at the invitation of the Cathedral Institute for Education and Formation, Colombo, Sri Lanka.)

In 1977, addressing the Colombo Diocesan Council, Bishop Abeynaike made the following observation:

‘The World in which we live today is a sick and hungry world. Torture, terrorism, persecution seem to be accepted as part of our situation…We do not have to be very perceptive in Sri Lanka to see that the foundations of our national life are showing signs of disintegration…While some are concerned about these things, many more are mere observers…A kind of despair seeps into us like a dark mist. Who am I to carry any influence, anyway? (The Colombo Diocesan Council Address by the Rt Revd C L Abeynaike at the Diocesan Council 1977, ‘What the World Expects’ Ceylon Churchman (January/February 1978) 11.)

Nearly five decades later, it feels like not much has changed, in the world or in how we perceive our helplessness in relation to our public life. Many of us saw the crisis of 2022 in Sri Lanka as a crisis of political representation. We felt that our elected representatives were not only failing to act in our interests but were, quite boldly, abusing their office to serve their own interests. While that was certainly one reason for that crisis, it was not the only one. Along with each elected representative who may have abused their power, there were also a number of other public officials who either enabled it or failed to prevent that abuse of power. For whatever reasons, such public officials – whether in public administration, procurement or law and order – acted in ways which led to our loss of trust in public office. When we look further, we can also see that systems of education, religious institutions and cultural practices nurtured and enabled public officials to act in ways that caused this loss of public trust. We often doubt whether this system can be salvaged. However, speaking in 1977, Bishop Abeynaike reminds us that these are challenges that we ought to face collectively, and I quote again:

‘But the longest journey begins with the first step. In politics, as in religion, faith without works is dead. We are caught up with unifying faces that create proximity and with divisive faces that disrupt community. We have to discover how to build community in proximity.’ (The Colombo Diocesan Council Address by the Rt Revd C L Abeynaike at the Diocesan Council 1977, ‘What the World Expects’ Ceylon Churchman (January/February 1978) 11-12)

In my view, that task of building ‘community in proximity’ includes reviving and strengthening our public discourse about public office that focuses on securing public trust. This is why I proposed to provide a Christian perspective on Securing Public Trust in Public Office for this year’s Abeynaike memorial lecture. In the next 50 minutes, I will suggest to you that public officials ought to nurture and cultivate five attributes: truthfulness, rationality, conviction, critical introspection and compassion. To illustrate the scope of these five attributes, I have chosen four examples. Let me present them to you now and as I present the five attributes, I will selectively refer back to these examples.

Example 01 : In 2002, in Kandy, a group of persons threw acid at Audit Superintendent Lalith Ambanwela. The reason for this attack was Ambanwela’s disclosure of a fraud of Rs 17.5 million in purchasing computers for the Central Province Dept. of Education in 2002 (Daily Mirror 25 May 2021). This acid attack caused Ambanwela grave and life-threatening harm. Unusual for cases of this nature, the accused were tried and convicted by the Kandy High Court. Referring to this judgement, Ambanwela said, and I quote, ‘This is a good judgment given on behalf of the future of the country. This is not my personal victory. It is a victory gained by government servants on behalf of good governance’(Judgement promoting good governance, TISL, 25 October, 2012). In 2004, the Sri Lanka chapter of Transparency International awarded Mr Ambanwela the National Integrity Award.

Example 02 : In 2014, South Africa’s Public Protector, Thuli Madonsela, published a report titled ‘Secure in Comfort’ (Report No 25 of 23/24, March 19, 2014). This was a report that concluded that the then President of South Africa had, among other things, enriched himself and his family by excessive spending to improve his private family home – purportedly to improve security. The President rejected the report and refused to comply with the decision that the misused public funds should be paid back. Over the next two years this battle for accountability continued. As Thuli Madonsela ended her term in October 2016, she finalised and fought to release another report, titled ‘State of Capture’ (Report No: 6 of 206/17). This report documented entrenched corruption involving a leading business family and President Zuma in which the public protector recommended a judicial inquiry commission. By early 2018, President Zuma resigned under threat of facing a no-confidence motion in Parliament, primarily over these two matters.

Example 03 : William Wilberforce was a British politician who lived in 18th century England. He was a member of the British Parliament, a leading figure in the Anit-Slavery movement of that time and, relevant for this lecture, a Christian. His first unsuccessful attempt at proposing the adoption of a law to prohibit the slave trade was in 1789. Since then, he failed 11 times in trying to bring about this law and eventually, 15 years later, he succeeded on the 12th occasion, in 1807. He then went on to push for the abolition of slavery itself but retired from politics in 1825. In 1833, 44 years since he began his anti-slavery work in Parliament and three days before his death, slavery was abolished in the United Kingdom (Slavery Abolition Act 1833).

Example 04 : In April 2022, Sri Lanka declared its first ever default from sovereign debt repayment. This default was a result of a worsening balance of trade over decades and due to a series of political and expert decisions that led Sri Lanka into a debt. As we all know, this was a time when the people mobilised peacefully, reacting to the systematic institutional failures and demanding a ‘system change’, particularly, but not limited to, a change in a system of governance headed by an Executive President. Much has been said about the events of 2022, but for the purposes of today’s talk, I would like to recall the several failures on the part of public officials, including of our elected representatives, that led us to this crisis point. People died, while waiting in queue, to pay and obtain fuel or gas. Such was the extent of that tragedy. Today, much of the cost of the mismanagement, negligence, abuse of power and recovery are borne by you and me, including for example the losses incurred by SriLankan Airlines.

Before I use these examples to present the five attributes of public office, permit me to explain what I mean by public office, the idea of securing public trust and describe what I understand to be a Christian perspective on both.

Public Office

We often associate elected representatives, or public servants, with the term public office. But I will use this term in a broader sense today. For the purposes of today’s talk, I include within the idea any office that requires the person holding that office to exercise power or authority under public law. This description would cover members of Parliament, the President, members of the Judiciary, the police and public servants. In the Sri Lankan context, it would also include university academics and members of what we commonly describe as independent commissions such as the Human Rights Commission and the Election Commission.

When we consider all these personnel at this general level, we must bear in mind that different limitations and protections apply to different types of public officials. For instance, the role of judges is unique and comes with extensive limitations and protections in contrast with the role of an elected representative. Members of the judiciary are diligently required to avoid not only actual conflicts of interests but also perceived conflicts of interest and, therefore, are often very selective in their public engagements unlike legislators. University academics enjoy academic freedom, a freedom not available to public servants. Doctors in the public health system enjoy professional discretion while members of the police are subject to a unique form of order and discipline. Broadly speaking, different types of public officials play a unique and essential role in sustaining our collective life which is why public trust on public officials assumes great significance.

Public Trust

Public trust is a concept that I have worked with for about 15 years in relation to public law in Sri Lanka. (The basic idea here is that anyone who exercises public power ought to exercise that power only for the benefit of the People. The ‘Public Trust Doctrine’ is a public law concept that seeks to enforce this idea in the law. In several jurisdictions in the world, the Public Trust Doctrine has been invoked by judges to recognise rights of the natural environment or rights to the natural environment and a corresponding duty on the state to respect such rights. In Sri Lanka, however, the public trust doctrine has been developed much more broadly by judges to review the exercise of executive discretion and to decide whether such discretion has been exercised for the benefit of the people or not. Examples of executive discretion would include the discretion that lies with the Executive President to grant a pardon to a convict, the discretion that lies with the Governor and Monetary Board of Sri Lanka to determine Sri Lanka’s monetary policy and the discretion that lies with the Cabinet of Ministers to manage state assets. Over the last three decades, Sri Lanka’s Supreme Court has developed the public trust doctrine to recognise that the exercise of public power must be reasonable, that it cannot be arbitrary and that it must only be for the benefit of the people. I draw from this idea of the public trust doctrine to ask a more ethical question as to what can be done to secure public trust, by public officials.

A Christian Perspective

How do we identify a Christian perspective on securing public trust? There are at least two approaches: one is the evangelical approach where we draw from the life of Jesus, and the second is the broader Anglican approach which combines the first, with the teachings of the Church as well. Of course, Christ did not exercise public power nor did he hold public office. But through his ministry and the Bible more generally, we learn about the Kingdom of God – its purpose and its value commitments. The calling for Christians is to internalise and practice the values of the Kingdom of God in all we do, including in our public lives and to offer that perspective to the rest of the world. For this talk, therefore, I derive my Christian perspective from the Bible, the teachings of the Church and through that from our collective understanding of the Kingdom of God. It is important to bear in mind that much of what we draw from our faith may resonate with the other faiths that are practiced in Sri Lankan society or may be explained in secular terms too.

I now turn to the main task I have set up for myself today – which is to try to interpret what a Christian perspective may have to offer in securing public trust in public office. I present my ideas through five attributes: 1) truthfulness, 2) rationality, 3) conviction 4) critical introspection and 5) compassion. I chose these attributes drawing on my study of the deficit of public trust in our public officials here in Sri Lanka but also from my own experiences.

· Truthfulness

Of the five attributes that I present to you today, truthfulness might be the one that is most familiar to us. Truthfulness is a common demand placed on us by most religions and can have an internal and an external dimension.

What do the scriptures have to offer us in this regard? Consider the example of Jesus in relation to the adulterous woman in the Gospel of John 8: 1-9. In that account, Jesus had significant power to influence how the religious establishment and the broader public would react to her and indeed, determine how she should be punished for being adulterous. In that moment, rather than exercise a harsh power of judgement, Jesus intentionally chose to take the path of truthfulness. The truthfulness that he exercised there had an internal or personal dimension as well as an external and structural dimension to it. At the internal or personal level, through his act, he demanded that those who sought to punish this woman, be truthful about their own conduct. But in doing so, he truthfully drew attention to the religious and cultural structures of that society which sought to selectively penalise and condemn women. The woman did not get a free pass either. Jesus asked her too, to be truthful and leave her life of sin.

A helpful contemporary challenge that we can apply these principles to would be the responsibilities of public officials to be truthful about practices such as corruption, ragging or sexual harassment internal to our public institutions. What does it mean, for a public official, to be truthful in the face of these deeply problematic and entrenched injustices within our public institutions and in the way in which these public institutions offer their services to society? In the context of holding public office, being truthful about these issues is often inconvenient, uncomfortable and has too many implications for the status quo. Being truthful often requires too much work. It causes persons who hold public office to become unpopular, disliked, be made of targets for retaliation and in some instances to even have to risk losing their jobs. It is useful to recall here that speaking the truth about himself, that is his claim to be the Messiah, led Jesus ultimately to his crucifixion.

Speaking truth to power is equally difficult and often can attract serious risks. In his brief public life of three years, Jesus did not hold back from speaking truth to power. One of my personal favourites is his description of the Pharisees as graves painted in white (Matthew 23:27). For public officers, speaking truth to power may entail calling out the abuse of power, refusing to engage in or endorse illegal actions and being willing to take action against wrongdoing.

Recall here my first example of the acid attack against Lalith Ambanwela. He nearly paid for his truthfulness with his life, is reported to have lost sight in one eye and his face was permanently disfigured. Why then, should public officials be truthful and in what ways would it help to secure public trust? From a Christian perspective, there are two ways to justify the attribute of truthfulness. First, it is an attribute that we practice for its intrinsic value. As Christians, we believe that the God of the Bible is true and practices truthfulness and requires the same of those who follow him. Followers of Christ are required to be lovers and seekers of the truth. The second reason is consequentialist. The Christian perspective requires that we are truthful because the absence of truth is a lie, an injustice and God abhors the lie as well as injustice. (To be continued)

By Dinesha Samararatne

Professor, Dept of Public & International Law, Faculty of Law, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka and independent member, Constitutional Council of Sri Lanka (January 2023 to January 2026)

Features

Making waves … in the Seychelles

The group Mirage, led by drummer and vocalist Donald Pieries, just returned from a little over a month-long engagement in the Seychelles, and reports indicate that it was a happening scene at the Lo Brizan pub/restaurant, Niva Labriz Resort.

The group Mirage, led by drummer and vocalist Donald Pieries, just returned from a little over a month-long engagement in the Seychelles, and reports indicate that it was a happening scene at the Lo Brizan pub/restaurant, Niva Labriz Resort.

The band even adjusted their repertoire to include local and African songs, and New Year’s Eve turned out to be a memorable event for the guests who turned up to usher in 2026.

The scene became active, around 8.00 pm, and the lead up to the dawning of the New Year was nostalgic as the crowd was on the floor, enjoying the music of Mirage.

As the New Year approached, the countdown began and then it was ‘Auld Lang Syne,’with everyone participating in the singing.

Enjoying the 31st night scene … on the dance floor

Mirage did six nights a week at the Lo Brizan and it was their fourth trip to the Seychelles, and they go back again this year – in April, August, and for the festive season in December.

Guests patronising this outlet, include French, German and Russian tourists, and locals, as well, and the group’s repertoire is made up of songs that include Russian, French and German, and the language spoken in the Seychelles, Creole, with female vocalist Danu being quite adaptive, singing in all four languages.

Many attribute the band’s success to Donald Pieries, including their recent engagement in the Seychelles.

Interestingly, Donald’s been with Mirage through various lineup changes, and he’s currently fronting an extremely talented lineup, made up of Sudham (bass/vocals), Gayan (lead guitar/vocals), Danu (female vocalist) and Toosha (keyboards).

Donald is also quite the family man – his 50th wedding anniversary was recently celebrated in style in the Seychelles.

In Colombo, Mirage will be obliging music lovers every Friday at the Irish Pub.

In fact, they went into action at the Food Harbour, Port City, Colombo, on the 23rd and 24th of this month.

Mirage: Extremely popular with the crowd at the Lo Brizan pub/restaurant, Niva Labriz Resort

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoComBank, UnionPay launch SplendorPlus Card for travelers to China

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoComBank advances ForwardTogether agenda with event on sustainable business transformation

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoRemembering Cedric, who helped neutralise LTTE terrorism

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoCORALL Conservation Trust Fund – a historic first for SL

-

Opinion2 days ago

Opinion2 days agoConference “Microfinance and Credit Regulatory Authority Bill: Neither Here, Nor There”

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoA puppet show?

-

Opinion1 day ago

Opinion1 day agoLuck knocks at your door every day

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoThe middle-class money trap: Why looking rich keeps Sri Lankans poor