Opinion

Numbers behind different COVID-19 vaccines

By M. C. M. Iqbal

The vaccines against COVID-19, available today, are based on different strategies and come with different numbers to indicate their performance. Many of us wish to know if one vaccine is better than the other. Two concepts underlying the performance of the vaccines are efficacy and effectiveness. The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine has an efficacy of 95 percent, the Moderna Vaccine is 94.5 percent and the Russian made Sputnik vaccine is over 90 percent. Does this mean some vaccines are better than the other? The short answer is no. All the approved vaccines are equally good. So, let us look at what these numbers mean.

These numbers refer to statistical calculations to interpret the results of vaccination trials conducted by the manufacturers of vaccines, following a prescribed format. The method of calculation was developed over 100 years ago by two statisticians, who published their results in the Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine in 1915. They, Major Greenwood (Major is his first name and not a military title) and Udny Yule, were tasked with interpreting the results of immunization of British soldiers against typhoid and cholera, who were fighting in different regions of Europe and Asia favourable to the development of cholera epidemics. In a paper stretching over 82 pages, the authors developed the theoretical and mathematical background for calculating the efficacy of vaccines.

This article seeks to explain to the lay reader what these numbers imply and to bring out the differences between efficacy and effectiveness of a vaccine.

Efficacy and effectiveness

At first sight these two terms appear to be synonyms. However, in the world of vaccines and medicine, these two terms are not the same. Efficacy of a vaccine is how it performs under ideal and controlled conditions in a clinical trial (see below). During clinical trials, the outcome of vaccination is compared between a group of vaccinated people and another group given an inactive form of the vaccine (called a placebo). The effectiveness of a vaccine is how the vaccine performs in the real world – that is after the vaccine is approved by the regulatory agencies and you and I are vaccinated.

The efficacy of a vaccine is measured by the manufacturers under ideal conditions in a clinical trial where criteria are specified for selecting and excluding volunteers. These criteria are usually age groups, gender, ethnicity, geographical location and socio-economic standing. If the criteria are specific, then the effects of the vaccine or drug would not be applicable across the population. For example, if the COVID-19 vaccines are not tested on children below 18 years, then the approved vaccine cannot be used on children.

The effectiveness of a drug or vaccine is a measure of how well the drug or vaccine performs in real life, in a diverse population: Fitness geeks and couch potatoes, housewives and nurses, and farmers and office workers. Effectiveness is of relevance to the medical community and healthcare authorities who are treating the patients. Thus, studies on effectiveness would look at to what extent the vaccine is beneficial to the patient to prevent infection.

One may ask, why not simply look at the effectiveness of the vaccine? This is because if the participants in an initial trial of the vaccine are not carefully controlled, then it is difficult to interpret the outcome of the trial. We have many characteristics, which can potentially interfere with the outcome of a trial testing a vaccine. The person volunteering for the trial could be young or old, pregnant or not, a marathon runner or an average person and smoker or non-smoker. Thus, the volunteers selected for the trials are very similar within their groups with many criteria to exclude persons who could confuse the results (for example, an unhealthy person with other diseases would be excluded).

Efficacy of a vaccine asks the question ‘Does the vaccine work under ideal conditions?’ On the other hand, a study on the effectiveness of the same vaccine asks the question ‘Does vaccination work in the real world?’

Clinical trials

Under normal circumstances, vaccines take many years of research and testing to be approved. The COVID-19 pandemic was unprecedented, and pharmaceutical companies embarked on a race against time to produce safe and effective vaccines. The genome of this coronavirus, which was discovered by Chinese scientists, in January 2020, was a major contribution to the development of the vaccines. At the moment there are 94 vaccines being tested on humans in clinical trials, 32 of which have reached the final stage of Phase 3 testing.

To obtain approval for a vaccine, the vaccine manufacturers go through a prescribed process to ensure that the vaccine is safe. All the countries have a national drug approval agency, who should approve the use of a drug or vaccine in that country. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States is an important regulatory agency, which has stringent criteria to approve medicines and drugs. In Sri Lanka, it is the National Medicines Regulatory Authority. COVID-19 vaccines are also assessed and approved by the WHO.

Initially, the vaccine is tested on cells in the laboratory and then given to animals, usually mice or monkeys. After this, if the mice or monkeys are happy, human volunteers are recruited to conduct the clinical trials, which is done in three phases. In the first phase, the vaccine is tested on a small group of people to determine the safety, dosage and ability to stimulate our immune system. If this is confirmed, the vaccine then moves into the Phase 2 stage where the safety of the vaccine is tested on hundreds of people who are split into different groups. Once these trials are successful, the vaccine moves to the final Phase 3 trials. Here thousands of people are recruited as volunteers. For the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine there were over 40,000 volunteers, above the age of 16, from different countries. This trial is more comprehensive, with the volunteers belonging to different age groups, physical fitness, ethnicities and geographical locations. The volunteers are divided into two groups. One group gets the real vaccine while the other group gets a fake vaccine or placebo (the syringe has just water). The volunteers would not know if he/she is getting the vaccine or a placebo and neither do the nurses and doctors giving the vaccine. This is called a double-blind clinical trial. Thus, no one knows, except those conducting the trial, who was vaccinated with what.

After some time, the volunteers, who fell sick with the coronavirus, are PCR tested to confirm if they are COVID-19 positive. The scientists will be on the lookout for any side effects of the vaccine; if they find any cause for concern the trial can be stopped temporarily to conduct investigations and remedy the problem. If the scientists are not satisfied, the trial would be abandoned. Once the results are in, the calculations are done, and all the details are submitted to the regulating authorities. The regulators would ask the manufacturers more questions and once they are satisfied, approval is given to manufacture and market the vaccine. To accelerate the process, such as now during the COVID-19 crises, Phase 1 and 2 may be combined and run in parallel.

Calculating efficacy

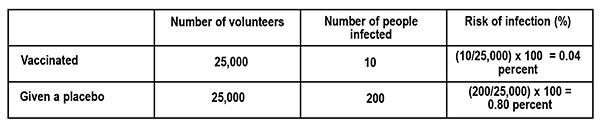

The calculations involved are quite simple once the data is collected. Let us assume that 50,000 volunteers were recruited for the vaccination trial. Half were given the vaccine and the other half a placebo. Let us assume that of the 25,000 who received the vaccine, 10 persons were infected, and of the other 25,000 who received the placebo, 200 were infected. Although the numbers of people infected are small, those in the placebo group are 20 times larger (see Table). The researchers are concerned with the relative risk between the groups. This is called the efficacy of the vaccine.

The risk of infection is calculated as follows.

What is the difference in the risk of infection between the vaccinated group and those who got the placebo? From the table this is, 0.80 percent – 0.04 percent = 0.76 percent.

Thus, the vaccine reduced the risk of infection by 0.76 percent, which looks quite small. This is what would happen if we are vaccinated. To understand this in terms of the risk of infection, if none were vaccinated, we look at the ratio of the Reduction in Infection (0.76 percent) to the Risk of infection (0.80 percent – those who got the fake vaccine). This is the Vaccine Efficacy (VE).

VE percent = Reduction in infection ÷ Risk of infection = 0.76 ÷ 0.80 = 95 percent

If this is still confusing, let us see what it means in a population of 100,000 persons who are vaccinated with a vaccine of 95 percent efficacy, and exposed to the virus. From the table above, the risk of infection for the vaccinated population is 0.04 percent, which translates to 40 persons (0.04 percent x 100,000). That is, we can expect that 40 persons would fall ill with an infection by the coronavirus and the rest of the vaccinated people may not develop an infection at all or develop an asymptomatic infection (you are infected but do not show symptoms) or get a mild disease.

(This example of calculating Vaccine Efficacy is adapted from an article by Dashiell Young-Saver in the New York Times of December 13, 2020, where the above calculation is explained in detail for students.)

What does efficacy mean?

The efficacy of a vaccine refers to two aspects. The first is how many of us are protected by the vaccine if we are exposed to the virus; this is given by the percentage. The vaccine also refers to different disease conditions it is capable of preventing. This could be causing an infection, mild disease, severe disease, hospitalisation, or death. This information can be found if one looks carefully at the statements issued by the vaccine manufacturer and regulatory agencies. For example, the statement by Pfizer-BioNTech states: Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine, BNT162b2, was 91.3 percent effective against COVID-19 (symptomatic cases of COVID-19), measured seven days through up to six months after the second dose. The vaccine was 100 percent effective against severe disease as defined by the US centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and 95.3 percent effective against severe disease as defined by the US FDA.

The efficacy of a vaccine (VE) is the relative reduction of being infected, if we are vaccinated, compared to the placebo or unvaccinated group. If the vaccine is perfect, then the risk of being infected is totally eliminated, so that VE = 1 or it is 100 percent. On the other hand, if there is no difference in the number of people infected between the two groups, the vaccine has no efficacy, or it is zero. Even with a perfect vaccine, our capacity to acquire an infection is determined by our age, health and immunity status.

In short, efficacy is a statistical measurement based on clinical trials of the vaccine’s ability to prevent infection. The volunteers taking part in the trials are not a perfect sample or representative of the real world (for example, children and sick people do not take part). Is there a lower limit for the efficacy of a vaccine to be accepted? Under the present circumstances, the FDA said it would consider granting emergency approval if the vaccines showed even 50 percent efficacy; the vaccines that have received approval now show an efficacy of over 90 percent.

Effectiveness

The effectiveness of the vaccine tells us how well the vaccine is performing among the population, in the real world, to prevent infection. The effectiveness of the vaccine depends on the impact it makes on society. After vaccination our immune system is primed to combat the coronavirus, reducing the multiplication of the virus in our body. This will gradually slow down the spread of the virus as more and more people are vaccinated. In other words, it is important that most if not all the people are vaccinated to have a large impact on the spread of the virus in society. Good examples are the smallpox vaccine, which completely eliminated the smallpox virus, and the polio vaccine, which has almost wiped out the polio virus except for a few small pockets in Pakistan, Afghanistan and Africa. Thus, the effectiveness of a vaccine looks at the medical and societal importance of the outcome.

Here is the above in a nutshell. The percentage numbers given with a vaccine refers to its efficacy – its ability to prevent an infection developing into a serious condition, determined under controlled clinical trials. Vaccines do not prevent infection – they prevent the infection from developing into a severe disease. Once we are vaccinated, our immune system is activated. If we are infected by the coronavirus, the virus has a small window of time to multiply, before it is eliminated by our immune system. This means we can release virus particles from our body, but much less than if we were not vaccinated. The message is we should get vaccinated with the first available vaccine and still wear our masks when going outside, even if we are vaccinated. The chances of ending up in a hospital is low and the chances of ending up in the ICU is very low. There is always a chance.

‘Tis impossible to be sure of anything but Death and Taxes (Christopher Bullock, 1716).

(M.C.M. Iqbal is Associate Research professor, Plant and Environmental Science, National Institute of Fundamental Studies, Hanthane Road, Kandy, and can be reached at iqbal.mo@nifs.ac.lk)

References

Zimmer, C. New York Times Nov. 20, 2020. Two companies say their vaccines are 95 percent effective. What does that mean?

Haelle,T. Association of Health Care Journalists. October 22, 2020. Know the nuances of vaccine efficacy when covering Covid-19 trials. https://healthjournalism.org/blog/2020/10/know-the-nuances-of-vaccine-efficacy-when-covering-covid-19-vaccine-trials/

Greenwood, M., & Yule, G. U. (1915). The Statistics of Anti-typhoid and Anti-cholera Inoculations, and the Interpretation of such Statistics in general. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, 8 (Sect Epidemiol State Med), 113–194.

Food and Drug Administration, US Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.fda.gov/media/139638/download

Opinion

A harsh reflection of Sri Lanka’s early-warning gap

Cyclone Ditwah:

Cyclone Ditwah, which swept across Sri Lanka at the end of November, caused massive damage to the country, the extent of which need not be mentioned here, as all are aware of it by now. Heated arguments went on among many parties with regard to how this destruction could have been mitigated and who should take responsibility. Although there may have been shortcomings in several aspects of how we responded to Ditwah, this article highlights a critical area that urgently requires attention if we are to protect ourselves from similar hazards in the future.

As is common in many situations, it has once again showcased a concerning weakness in the country’s disaster-management cycle, the gap between issuing early warnings and the expected public response. The Meteorological Department, the Irrigation Department, the National Building Research Organization, and other authorities issued continuous warnings to evacuate well in advance of imminent threats of flooding, landslides, and water hazards. However, the level of preparedness and community reaction fell short, leading to far greater personal property damage, including loss of a few hundred lives.

Sri Lanka is not unfamiliar with natural disasters. One of the most devastating disasters in our history could be considered the 2004 Tsunami event, which resulted in over 35,000 deaths and over $1 billion in property damage in the coastal belt. After the event, the concepts of disaster management were introduced to the country, which we have been adhering to since then. Again in 2016, the country faced massive river flooding, especially in western and southern regions, and until recently experienced repeated floods and landslides due to rains caused by atmospheric disturbances, though less in scale. Each of these events paved the way for relevant authorities to discuss and take appropriate measures on institutional readiness, infrastructure resilience, and public awareness. Yet, Cyclone Ditwah has demonstrated that despite improvements in forecasting and communication, well supported by technological advancements, the translation of warnings into action remains critically weak.

The success of early-warning systems depends on how quickly and effectively the public and relevant institutions respond. In the case of Ditwah, the Department of Meteorology issued warnings several days beforehand, supported by regional cyclone forecasting of neighbouring countries. Other organisations previously mentioned circulated advisories with regard to expected flood risk and possible landslide threats on television, radio, and social media, with continuous updates. All the flood warnings were more than accurate, as low-lying areas were affected by floods with anticipated heights and times. Landslide risks, too, were well-informed for many areas on a larger spatial scale, presumably due to the practical difficulties of identifying such areas on a minor scale, given that micro-topography in hill country is susceptible to localised failures. Hence, the technical side of the early-warning system worked as it should have. However, it is pathetic that the response from the public did not align with the risk communicated in most areas.

In many affected areas, people may have underestimated the severity of the hazard based on their past experiences. In a country where weather hazards are common, some may have treated the warnings as routine messages they hear day by day. As all the warnings do not end up in severe outcomes, some may have disregarded them as futile. In the meantime, there can be yet another segment of the population that did not have adequate knowledge and guidance on what specific actions to take after receiving a warning. This could especially happen if the responsible authorities lack necessary preparedness plans. Whatever the case may be, lapses in response to early warnings magnified the cyclone’s impact.

Enforcing preventive actions by authorities has certain limitations. In some areas, even the police struggled to move people from vulnerable areas owing to community resistance. This could be partly due to a lack of temporary accommodation prepared in advance. In some cases, communities were reluctant to relocate due to concerns over safety, privacy, and the status quo. However, it should be noted that people living in low-lying areas of the Kelani River and Attanagalu Oya had ample time to evacuate with their valuable belongings.

Hazard warnings are technical outputs of various models. For them to be effective, the public must understand them, trust them, and take appropriate action as instructed. This requires continuous community engagement, education, and preparedness training. Sri Lanka must therefore take more actions on community-level disaster preparedness programs. A culture of preparedness is the need of the day, and schools, religious institutions, and community-based organisations can play an important role in making it a reality. Risk communication must be further simplified so that people can easily understand what they should do at different alert levels.

Cyclone Ditwah has left, giving us a strong message. Even an accurate weather forecast and associated hazard warnings cannot save lives or property unless the public responds appropriately. As it is beyond doubt that climate change intensifies the frequency and severity of extreme weather events, people in Sri Lanka have to consider preparedness as a routine part of life and respond to warnings promptly to mitigate damage from future disasters.

(The writer is a chartered Civil Engineer)

by Eng. Thushara Dissanayake

Opinion

Feeling sad and blue?

Here is what you can do!

Comedy and the ability to have a good laugh are what keep us sane. The good news to announce is that there are many British and American comedy shows posted up and available on the internet.

They will bring a few hours of welcome relief from our present doldrums.

Firstly, and in a class of its own, are the many Benny Hill shows. Benny is a British comedian who comes from a circus family, and was brought up in an atmosphere of circus clowning. Each show is carefully polished and rehearsed to get the comedy across and understood successfully. These clips have the most beautiful stage props and settings with suitable, amusing costumes. This is really good comedy for the mature, older viewer.

Benny Hill has produced shows that are “Master-Class” in quality adult entertainment. All his shows are good.

Then comes the “Not the Nine o’clock news” with Rowan Atkinson and his comedy team producing good entertainment suitable for all.

And then comes the “Two Ronnies” – Ronnie Barker and Ronnie Corbett, with their dry sense of humour and wit. Search and you will find other uplifting shows such as Dave Allen, with his monologues and humour.

All these shows have been broadcast in Britain over the last 50 years and are well worth viewing on the Internet.

Similarly, in The USA of America. There are some really great entertainment shows. And never forget Fats Waller in the film “Stormy Weather,” where he was the pianist in the unforgettable, epic, comedy song “Ain’t Misbehavin”. And then there is “Bewitched” with young and glamorous Samantha Stevens and her mother, Endora who can perform magic. It is amazing entertainment! This show, although from the 1970s was a milestone in US light entertainment, along with many more.

And do not overlook Charlie Chaplin and Laurel and Hardy, and all the Disney films. Donald Duck gives us a great wealth of simple comedy.

The US offers you a mountain of comedy and good humour on Youtube. All these shows await you, just by accessing the Internet! The internet channel, ‘You tube’ itself, comes from America! The Americans reach out to you with good, happy things right into your own living room!

Those few people with the ability to understand English have the key to a great- great storehouse of uplifting humour and entertainment. They are rich indeed!

Priyantha Hettige

Opinion

There is much to learn

After the recent disaster, a great deal of information has been circulating on WhatsApp and YouTube regarding our reservoirs, highways, etc.

In many of these discussions, people have analysed what went wrong and how the damage could have been prevented. My question is this: why do all these knowledgeable voices emerge only after disaster strikes? One simple reason may be that our self-proclaimed, all-knowing governing messiahs refuse to listen to anyone outside their circles. It is never too late to learn, but has any government decision-maker read or listened to these suggestions?

When the whole world is offering help to overcome this tragedy, has the government even considered seeking modern forecasting equipment and the essential resources currently not available to our armed forces, police, and disaster-management centres?

B Perera

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoCabinet approves establishment of two 50 MW wind power stations in Mullikulum, Mannar region

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoGota ordered to give court evidence of life threats

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoCliff and Hank recreate golden era of ‘The Young Ones’

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoSri Lanka and Global Climate Emergency: Lessons of Cyclone Ditwah

-

Latest News7 days ago

Latest News7 days agoSri Lanka squad named for ACC Men’s U19 Asia Cup

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoExperience vs. Inexperience

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoWFP scales up its emergency response in Sri Lanka

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoSpecial programme to clear debris in Biyagama