Features

NMSJ Proposals for a New Constitution – Part I

By Dr Jayampathy WickramaratnE

President’ Counsel

The government has stated that it will unveil its proposals for a new Constitution in the form of a legal text early next year. A committee, headed by Romesh De Silva PC, has been working on a new Constitution for more than a year. It is not known whether the committee report would also be published. Whether the draft is based solely on the report or whether the Government’s proposals have also been included is to be seen.

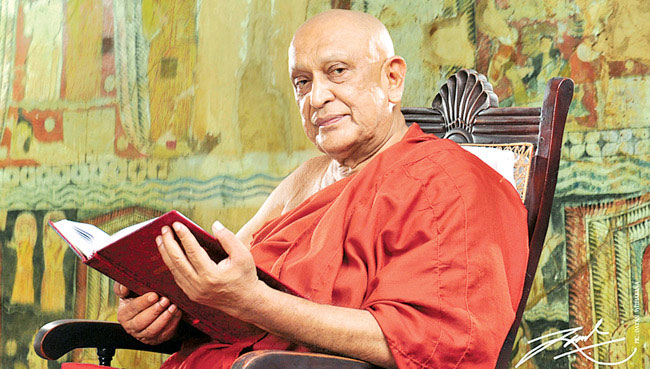

In the meantime, the National Movement for Social Justice (NMSJ) has unveiled its proposals on constitutional reform. The NMSJ, which the late Ven. Maduluwawe Sobitha Thera founded, has made a significant contribution to the debate on constitutional reform during its decade-long existence. Ven. Sobitha Thero was at the forefront of the campaign for the abolition of the executive presidency from the time it was installed in 1978 until he passed away in November 2015. He played an important role in the regime change of 2015 and, by his leadership, contributed to the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution. The late Thera was deeply disappointed that the Nineteenth Amendment was not up to his expectations.

The NMSJ’s proposals on selected aspects relating to democratic governance are a culmination of almost a year’s work. Several discussions open to all were held in cyberspace on various aspects of the Constitution. Experts were invited to present their proposals for reform, followed by long Q&A sessions. Draft proposals were circulated among NMSJ members, and a consensus was achieved. The NMSJ is now chaired by Karu Jayasuriya, former Speaker of Parliament. The writer has been associated with the NMSJ from almost its inception.

Constitutional Principles, Nature of the State, Sovereignty and Safeguards Against Secession

The description of the Sri Lankan state as ‘unitary’ in 1972 and its subsequent entrenchment in 1978 have impeded efforts at meaningful power-sharing. In constitutional theory, a unitary state is one in which the central government is supreme, and administrative divisions exercise only powers that the central government delegates. In short, there is only one ultimate source of state power. However, for many Sri Lankans, ‘unitary’ means ‘oneness’ or ‘one country’. The Sinhala word for ‘unitary’ is ‘ekeeya’, and ‘eka’ is ‘one’. Thus, changing the ‘ekeeya’ nature of the state is seen by some as ‘dividing’ the country.

Proponents of devolution argue that describing the Sri Lankan State as ‘unitary’ in the English version of the Constitution is undesirable for the reason that there exists a certain ‘unitary mindset’ in Sri Lanka according to which any issue that arises between the Centre and a Province is decided in favour of the Centre. They argue that while ‘unitary’ means in the classic sense that powers devolved may be withdrawn by the Centre by constitutional change, there have been instances of the legislature, executive and even the judiciary undermining devolution. They are agreeable to the use of the phrase ‘aekiya raajyaya’.

The Steering Committee of the Constitutional Assembly of the last Parliament considered the above mentioned claims and suggested a way out. The Committee stated: “The President whilst speaking on the Resolution to set up the Constitutional Assembly, stated that whilst people in the south were fearful of the word ‘federal’, people in the north were fearful of the word ‘unitary.’ A constitution is not a document that people should fear. The classical definition of the English term ‘unitary state’ has undergone change. In the United Kingdom, it is now possible for Northern Ireland and Scotland to move away from the union. Therefore, the English term ‘Unitary State’ will not be appropriate for Sri Lanka. The Sinhala term ‘aekiya raajyaya’ best describes an undivided and indivisible country.”

‘Orumiththa nadu’, the Tamil phrase for ‘aekiya raajyaya’ proposed by the Steering Committee, evoked controversy. The EPDP argued that ‘orumiththa nadu’ means, in essence, a ‘united state’ and suggested that the phrase used in the Tamil version of the 1978 Constitution ‘ottaiyadchi’ be used. The TNA claimed that ‘ottaiyadchi’ means ‘one government’ and not ‘one State’.

The NMSJ has proposed that the phrase ‘aekiya raajyaya’ be used in both the Sinhala and English versions and the correct term in Tamil be found and used in the Tamil version.

According to the NMSJ’s proposals, Sri Lanka would be an aekiya rajyaya, consisting of the institutions of the Centre and of the Provinces, which shall exercise power as laid down in the Constitution. An aekiya rajyaya is defined as a State which is undivided and indivisible and in which the power to amend the Constitution or to repeal and replace the Constitution shall remain with the national legislature and the People of Sri Lanka as provided in the Constitution. Sovereignty is in the People and is inalienable and includes the powers of government, fundamental rights and the franchise. The legislative, executive, and judicial power of the People shall be exercised as provided for by the Constitution.

Some fear that a Provincial Council might use its powers to move towards secession. To assuage such fears, the NMSJ has proposed that the Centre should have the power to intervene if there is a danger to the territorial integrity and sovereignty of the country. Accordingly, where a situation has arisen in which a provincial administration is promoting armed rebellion or insurrection or engaging in an intentional violation of the Constitution which constitutes a clear and present danger to the territorial integrity and sovereignty of the Republic, the Centre may by Proclamation assume all or any of the functions of the administration of the Province and, where necessary, dissolve the Provincial Council. To ensure that such power is not abused, it is proposed that the Centre give reasons for the exercise of the power, that Parliament should approve any such intervention and that an intervention should be subject to judicial review.

Legislature

The NMSJ has proposed a bicameral legislature composed of a Parliament and a Second Chamber suitably named. The term of Parliament shall be five years.

Parliament shall be dissolved by the President if Parliament passes a motion of no-confidence in the government or the Budget is defeated in or the Statement of Government Policy is defeated and a new government formed does not win a vote of confidence within 14 days. Parliament shall also be dissolved if a motion in the name of the Prime Minister to that effect, tabled with the agreement of the Leader of the Opposition and the leader of the third-largest party in Parliament, is passed. The President shall not dissolve Parliament other than in the above mentioned circumstances.

At present, a Member of Parliament who loses membership of the party or group on whose list s/he was elected consequently loses her/his seat in Parliament. But such Member may challenge the expulsion in the Supreme Court. In practice, however, such Members obtain injunctions from the District Court preventing any disciplinary proceedings and thereby frustrate the purpose of the anti-defection provision. This was sought to be remedied by the Nineteenth Amendment. Still, the proposed provision had to be withdrawn at the committee stage in Parliament due to the Opposition not being in favour. The NMSJ proposal is for the Supreme Court to have exclusive jurisdiction to hear and determine any matter relating to disciplinary action taken or proposed to be taken by any recognised political party or independent group against a Member of Parliament. No other court shall have the power to grant a writ, injunction, an enjoining order or any other relief, preventing, restraining or prohibiting any such action or proposed action.

The NMSJ points out that a second chamber of the legislature has been used in many countries as an instrument of power-sharing. Almost every country with devolution has such a chamber. A second chamber comprising representatives from the provinces would engender in the provinces a strong feeling that they too have a distinct role to play in the national legislature. It would function as a mechanism to rectify possible imbalances of representation in the lower house and also act as an in-built mechanism against hasty legislation and legislation that may have an adverse effect on the provinces.

The Second Chamber shall consist of 55 Members, each Provincial Council (PC) nominating five members based on a Single Transferable Vote, the method used under the Independence Constitution to elect Senators. As to who shall be members, two options have been given. Option 1: Members shall be persons of eminence and integrity who have distinguished themselves in public or professional life. Option 2: Members nominated will be PC members, including Provincial Ministers.

The Second Chamber shall not have the power to veto ordinary legislation. All Bills placed on the Order Paper of Parliament shall be referred to the Second Chamber to obtain its views, if any, before the Second Reading. A Bill seeking to make national policy or standards on a subject or matter in the Provincial Council List shall, however, be passed by the Second Chamber as well. The Second Chamber shall also exercise such oversight and other functions as may be prescribed by the Constitution or law. No Constitutional Amendment shall be enacted into law unless passed by both Parliament and the Second Chamber, with special (2/3) majorities.

(Next: The Executive and devolution)