Features

Mrs. B becomes PM and I the Secretary to the world’s first woman prime minster

Anura bothered about his mother seeing his school report before he did

(Excerpted from Rendering Unto Caesar, by Bradman Weerakoon, Secretary to the Prime Minister)

In 1960, as she rode to power, after a grueling campaign, as the world’s first-ever woman prime minister, Sirima Bandaranaike was making the global headlines and taking Ceylon too into the limelight, which was to last for decades. The world wondered as to how this phenomenon, of a woman being chosen to be prime minister, had occurred in Ceylon. Was it some peculiar provision of dynastic succession by which the wife succeeded to a vacancy caused by the death of a husband Could such a thing occur only in an Asian country? Was it, as uncharitable political opponents would say, a consequence of the enormous wave of sympathy that followed close on the tragic death of a popular leader? Was the phenomenon connected mystically with the primacy of motherhood’ (matar) so central a part of the culture of the Indian subcontinent?

There appeared to be some validity in each of these propositions. It took six years more before Indira Gandhi became India’s first woman prime minister. Then followed Golda Meir of Israel and thereafter several others. The breach had been opened and we had been the first to do it. I was going to have the privilege of being the secretary of the first woman prime minister of the world.

The election of a woman head of government was so unusual, that the newspapers were not sure what to call her. “There will be need for a new word. Presumably, we shall have to call her a Stateswoman,” London’s Evening News wrote stuffily on July 21, 1960. “This is the suffragette’s dream come true,” said another.

She was born Sirimavo Ratwatte on 17 April 1916, in Balangoda at the family home and married Solomon Dias Bandaranaike, then minister of local government and health in the State Council, in 1940. He was seventeen years older than her when they married. She claimed no particular political philosophy herself. Her purpose in coming into politics, as she often said, was to complete the visionary work which her husband had begun.

During the March 1960 election called by W Dahanayake, the SLFP was led by C P de Silva and she did not contest. In support of the party she said, “I am not seeking power but I have come forward to help the SLFP candidates so that the party can continue the policy of my late husband.”

The results of the March 1960 general elections were inconclusive. Under C P de Silva’s leadership the SLFP did tolerably well, winning 44 seats as against the UNP’s 50. What was however lacking in the SLFP campaign effort was the charismatic leadership and negotiating skills, which had brought about the coalition of anti-UNP forces, the Mahajana Eksath Peramuna or MEP under S W R D Bandaranaike.

Dudley Senanayake’s government of that time (March to July 1960) was the shortest in the history of Ceylon and he was forced to call another general election in July of the same year.

As the parties geared up for the polls, Sirimavo was prevailed upon to accept the presidentship of the party on 24 May 24, 1960. It was proclaimed on that occasion that in the event of the SLFP winning, Mrs Bandaranaike would be the prime minister.

For Sirimavo, the eight months that elapsed between the death of her husband and her assumption of the leadership of the Sri Lanka Freedom Party was a period of intense introspection. Where did her principal obligations lie? With her young family of two daughters, Sunethra and Chandrika and son Anura, now bereft of their father’s guidance? Or with his political party, which was now deprived of his leadership?

During the period of mourning she had publicly expressed her distaste for politics. She had seen her husband betrayed and killed. She was once reported to have said that she “would not take the prime ministership even if it was handed to me on a platter!”

But once she realized that without her, the SLFP would never form a stable government, her fighting qualities and determination took over. With the help of her cousin Felix R Dias Bandaranaike, a No-contest Pact with the LSSP and the CP was entered into in May 1960. This was “to permit the widest mobilization of forces to defeat the UNP” and it ensured for Sirimavo an epic victory. She emerged as the first woman prime minister in the world.

The primary motivation that drove her to accept what was, personally for her, an unattractive job, was her conviction that no other person as leader could fulfill the yet unachieved goals set by her late husband. This was manifested in her first message to the nation:

By their verdict the people have clearly affirmed their faith in the democratic socialist policies initiated by my late husband. It was far from my mind to achieve any personal glory for myself when I assumed the leadership of the party at the request of its leaders. I knew that if I did not take this step the forces of reaction would once again begin to oppress the masses for whose salvation my husband sacrificed his very life.

The speech set some important trends in political thinking. Foremost among them was the idea that the ‘forces of reaction’ had done Mr Bandaranaike to death and that Mr Bandaranaike had `sacrificed his life for the masses’. It was a powerful line, which persisted for a long time.

But there were many, including some of her close relatives, who doubted whether the untried widow of a great leader could so easily step into his shoes. How could an eminently respectable Sinhala Buddhist woman, whose life had centered around family and home, handle the manifold challenges of an emerging nation state? P E P Deraniyagala, a cousin of the late S W R D and best-man at the wedding in 1940, reflected this sentiment pithily when he said, “What does she know of politics? In Solla’s (Solomon’s) time Sirima presided over nothing fiercer than the kitchen fire. She’ll end by spoiling her personal reputation and ruining the family name.”‘ He, and others like him, were soon to find themselves in serious error.

The woman who was to be the world’s first prime minister was made of sterner stuff than her detractors envisaged. As she articulated on her role, she was to say:

I feel most strongly that home is a woman’s foremost place of work and influence, and looking after her children and husband are duties of the highest importance. But women also have their vital role in civic life, they owe a duty to their country, a duty which cannot and must not be shirked, and at least some of their time should be devoted to social welfare work.

Yet critics were still to refer to her lack of any outstanding attainments as she entered the highest office. She brought with her no university degree, parliamentary experience or administrative knowledge. But what she had were formidable enough – personal magnetism to draw the masses; ability to command the loyalty and respect of her ministerial colleagues; and the ability to convince the public that she was a woman of good moral character who would be honest in her public dealings.

Her background supported these basic claims for leadership. Sirimavo Bandaranaike hailed from an upper-class Kandyan family with a long feudal background. She had a grooming from childhood for working with people, for people, and social service came naturally to her. It was almost a case of noblesse oblige as in the training of the European nobility in feudal times. She was also the eldest in a family of five boys and two girls and had from early childhood assumed a position of leadership in the family.

Soon after leaving St Bridget’s Convent, a leading Catholic school for girls in Colombo, (although Sirimavo always was a devout Buddhist) she became an active member of the Lanka Mahila Samiti, perhaps the oldest and largest women’s social service association in the country. The Lanka Mahila Samiti was formed in 1931 – the year Sri Lankan women received the right to vote – through the initiative of Dr Mary Rutnam, a Canadian who was inspired by the women’s institutes of Canada. Sirimavo always acknowledged her debt to the Mahila Samiti for giving her the confidence to speak in public and move easily and knowledgeably rural folk.

Sirimavo settled easily into her work schedule as prime minister. She decided to shift into Temple Trees, leaving 65, Rosmead Place its painful memories to be looked after by a caretaker.

The picture (overleaf) is of her first day in office with me by her side. I was thirty years old. The office is the same as that used by the former prime minister – Ranil Wickremesinghe.

With three lively children in the house Temple Trees became, once again after a long period of hibernation, a place not only official work, files, quick movement and hustle and bustle but a place with the added delight of a background of children’s games, laughter, chatter and music. She rarely used her official room in the Fort Office in Senate Square where the prime minister’s main secretariat was located, being quite happy to operate from the guesthouse section of Temple Trees.

This part of the building constructed to accommodate state visitors, housed some modest office space and it was here that the prime minister, the private secretary and myself spent most of our official time. Dr Seevali Ratwatte, the prime minister’s younger brother came in as private secretary initially and he was succeeded in a few months by elder brother Mackie who himself was a medical practitioner.

Mr. Bandaranaike’s personal assistants Amerasinghe, and the ever-smiling Piyadasa were always on hand to help meet constituents from Attanagalla, Mr Bandaranaike’s electorate, and sundry droppers- in at Temple Trees. It was Amerasinghe who was there by Mr Bandaranaike’s side when he lay injured on the floor, and who had telephoned me to announce that, “Lokka has been shot.”

The main part of the prime minister’s office continued in the Fort and most public mail was received there. Dharmasiri Pieries, a young civil service cadet of great promise whom I had chosen, held the position of assistant secretary. He had a table on a side of my room and ably held the ‘fort’, while I spent most of my official time at Temple Trees. The mass of correspondence, which came in daily and did not need to be personally seen by the prime minister, was dealt with expertly and expeditiously by about 15 experienced Subject clerks who knew by long experience exactly what to do to keep business moving.

They were supervised by Francis Samarasinghe MBE, the office assistant, a man who had been inducted by D S Senanayake’s secretary, the meticulous and highly efficient N W Atukorale. He and C. Nadarajah, the chief clerk, ran a tight ship and could be virtually given a free hand. The confidential stenographer to the prime minister, Linus Jayewardene, whom I used almost exclusively since the prime minister did not dictate letters personally, was a character, and a priceless asset. He was one of the quickest and most accurate of stenographers, except on ‘race days’ when he would need to take-off, to place a bet or two with the bookies who operated on the sly, taking ‘all ons’ on the foreign horse races. Linus could always be trusted to have in his drawer a copy of the latest ‘Racing Form’. He was also a keen and appreciative connoisseur of female beauty and would often, and quite unprompted, keep me updated on the current best female form in town.

As a concession to her unfamiliarity with the parry and thrust of parliamentary debate, Sirimavo choose to sit in the Senate during her first five years as prime minister. The Senate, (the Soulbury Constitution provided for a bicameral legislature), consisted of 30 members. Fifteen were appointed by the governor-general on the recommendation of the prime minister and 15 elected by the lower House. One-third of the membership retired every second year so the government and Parliament alike had the opportunity to infuse new blood.

Like the House of Lords in the British Parliament, it had little power of its own and its principal objective was to subject legislation to a second opinion, the approval of both Houses being necessary to secure the passage of legislation. However, at most times it acted only as a rubber stamp, hardly ever amending or refusing its consent to bills sent up from the other House.

Proceedings in the Senate, whose president then was Sir Cyril de Zoysa, a member of the UNP and one time bus-transport magnate, were sedate and unemotional, the members being generally non-politicians, although favoured by the party which put them forward.

The SLFP got one of its senators to resign and Mrs Bandaranaike was duly appointed in his place by the governor-general. Although some cabinet minsters had earlier come from the Senate – the minister of justice invariably being a senator, the prime minister, the chief executive and the head of the government, had never ever before been from the Senate. This led to quite a lot of critical comment especially from the opposition in the Lower House, the House of Representatives. “Who was to reply to questions of policy if the prime minister was in the Senate?” was the constant refrain.

The leader of the House, C P de Silva, would explain the circumstances which had led to Mrs Bandaranaike not contesting the elections, but this was usually countered by the argument that she could as well have asked one of her own members of parliament to resign from the House and come into Parliament by contesting that seat at a by-election. I recall a minister, at an especially heated debate during which the issue was brought up, who was greeted with howls of protest by the LSSP, when he intemperately suggested that the House, considering the way some members behaved, was no place for a lady.

The fact that the prime minister – the fount of power and the harbinger of change – was not present in the House certainly affected the style and content of the administration. The Temple Trees office, where the prime minister held court each day, assumed an importance of its own. Persons who were close to the prime minister – either through being Mr Bandaranaike’s loyalists, or newer ones like Felix and J P Obeyesekera, became the intermediaries who carried the news of parliamentary proceedings and gossip to the prime minister. Inevitably Sirimavo lost that close touch with her parliamentary colleagues which she could have had if she had been a regular member of parliament. As a result, dissension and the formation of cliques could not be effectively countered in time, and various power groups and ‘young turks’ began to manifest themselves shortly thereafter.

The loneliness that the top position generates and which Sirimavo was soon to experience, was moderated to some extent by Felix Bandaranaike who at the age of 29 years and a newcomer to politics and Parliament, held the powerful post of minister of finance and parliamentary secretary to the minister of defence and external affairs. Both Felix and his wife Lakshmi, who was his private secretary, were relatives as well as good friends, and were so close that they were usually on a first-name basis with ‘Sirima’ as they called the prime minister, except in public and official occasions. They were both enormously loyal to Sirimavo, committed to the party and its causes, hard-working and brilliant strategists. They naturally aroused considerable jealousy, especially from the older party stalwarts, and even from close family members, and continued to face, throughout their association with Sirimavo a largely concealed, but nevertheless acute, hostility from many sides.

C P de Silva led the party in the House while Felix Dias represented Sirimavo in the many spirited battles in Parliament. This gave Sirimavo the space to deal, unhindered by the heat of parliamentary debate, with the-many domestic and foreign challenges then emerging. But it had its downside. It eventually led to the creation of wide spaces between her and the rank and file of the party membership and this unfortunate alienation encouraged the formation of cliques and dissenting groups.

For the first time since independence, the prime minister was to be from the Senate. Her seat in the front row of the House of Representatives remained vacant throughout the period of that Parliament. The vacant seat was symbolic of the fact that the prime minister was in the ‘other place’, but that her virtual presence was in the Lower House. In fact what happened was that Felix took on the role of answering questions addressed to her in his capacity as parliamentary secretary to the ministry of defence and external affairs.

It further added to my duties. When the Senate sat, I sat in the Gallery, there being no Officials Box, assisting as necessary with notes to the prime minister from there. When the House of Representatives sat and important Bills were taken up, or at the adjournment debate at the end of the day, I would sit in the Officials Box in the House and monitor what was happening. It added to my work, and my moving around, but it was one way Sirimavo’s great interest in what was going on in Parliament could be assuaged.

The economy and the budget, at the beginning of the sixties, were the sites of the early problems Sirimavo had to face. The worsening of the terms of trade made rationing and import substitution inevitable. There was a shortage of foreign exchange and I recall that travelers abroad were restricted at one point, to a sum of three Sterling pounds and fifty pence as their travel allowance. Visits abroad for education and medical treatment were strictly limited. This raised great problems for Sirimavo when it became time for Sunethra – her elder daughter – to go to Oxford.

The father had always wanted the children to have their final education abroad. So Sunethra, who had been a bright student at St Bridget’s Convent and easily passed the qualifying tests, gained admission to Somerville College. Foreign exchange was a problem, and Sirimavo was not going to bend the rules for her children. Arrangements were made for a relative – Michael Dias, brother of Felix Bandaranaike, who was a lecturer at Cambridge – to help out. The documentation was all in order, the Exchange Control authorities were happy and the entire procedure was very open and straightforward.

However, the press was not going to leave this alone and the usual critical comments about the children of privileged families getting special facilities while the others had to go the `aswa vidyalaya”, etc – a portion of the university being then conducted at the former Grandstand of the race course on Reid Avenue – continued for some time. I remember Sunethra, who hated publicity, being much put out by all the fuss and bother.

Sirimavo always took a great interest in the children’s schooling. Anura who was then 12 or 13 years old and attending Royal College was a constant concern, as he still had not settled down to the grind of study and homework. He would often be playing cricket in the large back lawn or declaiming, very much in the manner of a speaker on a political platform, to his admiring team-mates. When the holidays commenced, after the term tests were over, time of extreme anxiety for Anura. I would see him hovering around the office area in anticipation of the arrival of his school report. He wanted to have a look before the document was seen by the prime minister. I had quite a problem deciding whether I should show it to him first or put it up to the mother.

Features

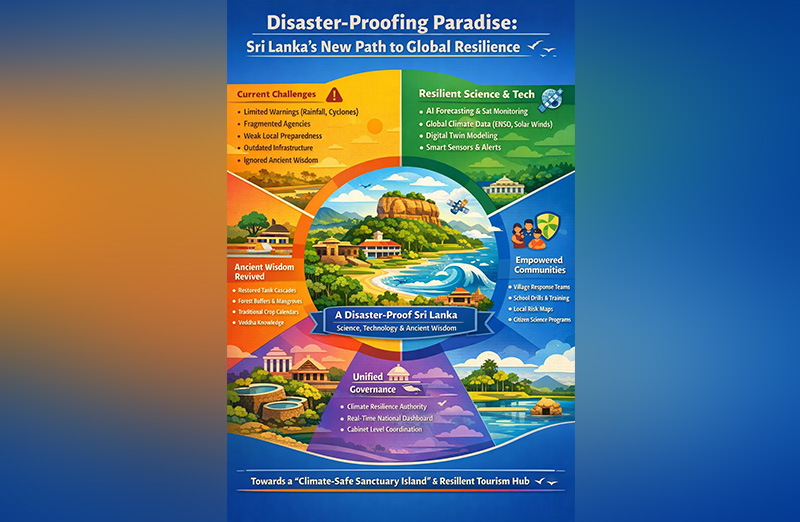

Disaster-proofing paradise: Sri Lanka’s new path to global resilience

iyadasa Advisor to the Ministry of Science & Technology and a Board of Directors of Sri Lanka Atomic Energy Regulatory Council A value chain management consultant to www.vivonta.lk

As climate shocks multiply worldwide from unseasonal droughts and flash floods to cyclones that now carry unpredictable fury Sri Lanka, long known for its lush biodiversity and heritage, stands at a crossroads. We can either remain locked in a reactive cycle of warnings and recovery, or boldly transform into the world’s first disaster-proof tropical nation — a secure haven for citizens and a trusted destination for global travelers.

The Presidential declaration to transition within one year from a limited, rainfall-and-cyclone-dependent warning system to a full-spectrum, science-enabled resilience model is not only historic — it’s urgent. This policy shift marks the beginning of a new era: one where nature, technology, ancient wisdom, and community preparedness work in harmony to protect every Sri Lankan village and every visiting tourist.

The Current System’s Fatal Gaps

Today, Sri Lanka’s disaster management system is dangerously underpowered for the accelerating climate era. Our primary reliance is on monsoon rainfall tracking and cyclone alerts — helpful, but inadequate in the face of multi-hazard threats such as flash floods, landslides, droughts, lightning storms, and urban inundation.

Institutions are fragmented; responsibilities crisscross between agencies, often with unclear mandates and slow decision cycles. Community-level preparedness is minimal — nearly half of households lack basic knowledge on what to do when a disaster strikes. Infrastructure in key regions is outdated, with urban drains, tank sluices, and bunds built for rainfall patterns of the 1960s, not today’s intense cloudbursts or sea-level rise.

Critically, Sri Lanka is not yet integrated with global planetary systems — solar winds, El Niño cycles, Indian Ocean Dipole shifts — despite clear evidence that these invisible climate forces shape our rainfall, storm intensity, and drought rhythms. Worse, we have lost touch with our ancestral systems of environmental management — from tank cascades to forest sanctuaries — that sustained this island for over two millennia.

This system, in short, is outdated, siloed, and reactive. And it must change.

A New Vision for Disaster-Proof Sri Lanka

Under the new policy shift, Sri Lanka will adopt a complete resilience architecture that transforms climate disaster prevention into a national development strategy. This system rests on five interlinked pillars:

Science and Predictive Intelligence

We will move beyond surface-level forecasting. A new national climate intelligence platform will integrate:

AI-driven pattern recognition of rainfall and flood events

Global data from solar activity, ocean oscillations (ENSO, MJO, IOD)

High-resolution digital twins of floodplains and cities

Real-time satellite feeds on cyclone trajectory and ocean heat

The adverse impacts of global warming—such as sea-level rise, the proliferation of pests and diseases affecting human health and food production, and the change of functionality of chlorophyll—must be systematically captured, rigorously analysed, and addressed through proactive, advance decision-making.

This fusion of local and global data will allow days to weeks of anticipatory action, rather than hours of late alerts.

Advanced Technology and Early Warning Infrastructure

Cell-broadcast alerts in all three national languages, expanded weather radar, flood-sensing drones, and tsunami-resilient siren networks will be deployed. Community-level sensors in key river basins and tanks will monitor and report in real-time. Infrastructure projects will now embed climate-risk metrics — from cyclone-proof buildings to sea-level-ready roads.

Governance Overhaul

A new centralised authority — Sri Lanka Climate & Earth Systems Resilience Authority — will consolidate environmental, meteorological, Geological, hydrological, and disaster functions. It will report directly to the Cabinet with a real-time national dashboard. District Disaster Units will be upgraded with GN-level digital coordination. Climate literacy will be declared a national priority.

People Power and Community Preparedness

We will train 25,000 village-level disaster wardens and first responders. Schools will run annual drills for floods, cyclones, tsunamis and landslides. Every community will map its local hazard zones and co-create its own resilience plan. A national climate citizenship programme will reward youth and civil organisations contributing to early warning systems, reforestation (riverbank, slopy land and catchment areas) , or tech solutions.

Reviving Ancient Ecological Wisdom

Sri Lanka’s ancestors engineered tank cascades that regulated floods, stored water, and cooled microclimates. Forest belts protected valleys; sacred groves were biodiversity reservoirs. This policy revives those systems:

Restoring 10,000 hectares of tank ecosystems

Conserving coastal mangroves and reintroducing stone spillways

Integrating traditional seasonal calendars with AI forecasts

Recognising Vedda knowledge of climate shifts as part of national risk strategy

Our past and future must align, or both will be lost.

A Global Destination for Resilient Tourism

Climate-conscious travelers increasingly seek safe, secure, and sustainable destinations. Under this policy, Sri Lanka will position itself as the world’s first “climate-safe sanctuary island” — a place where:

Resorts are cyclone- and tsunami-resilient

Tourists receive live hazard updates via mobile apps

World Heritage Sites are protected by environmental buffers

Visitors can witness tank restoration, ancient climate engineering, and modern AI in action

Sri Lanka will invite scientists, startups, and resilience investors to join our innovation ecosystem — building eco-tourism that’s disaster-proof by design.

Resilience as a National Identity

This shift is not just about floods or cyclones. It is about redefining our identity. To be Sri Lankan must mean to live in harmony with nature and to be ready for its changes. Our ancestors did it. The science now supports it. The time has come.

Let us turn Sri Lanka into the world’s first climate-resilient heritage island — where ancient wisdom meets cutting-edge science, and every citizen stands protected under one shield: a disaster-proof nation.

Features

The minstrel monk and Rafiki the old mandrill in The Lion King – I

Why is national identity so important for a people? AI provides us with an answer worth understanding critically (Caveat: Even AI wisdom should be subjected to the Buddha’s advice to the young Kalamas):

‘A strong sense of identity is crucial for a people as it fosters belonging, builds self-worth, guides behaviour, and provides resilience, allowing individuals to feel connected, make meaningful choices aligned with their values, and maintain mental well-being even amidst societal changes or challenges, acting as a foundation for individual and collective strength. It defines “who we are” culturally and personally, driving shared narratives, pride, political action, and healthier relationships by grounding people in common values, traditions, and a sense of purpose.’

Ethnic Sinhalese who form about 75% of the Sri Lankan population have such a unique identity secured by the binding medium of their Buddhist faith. It is significant that 93% of them still remain Buddhist (according to 2024 statistics/wikipedia), professing Theravada Buddhism, after four and a half centuries of coercive Christianising European occupation that ended in 1948. The Sinhalese are a unique ancient island people with a 2500 year long recorded history, their own language and country, and their deeply evolved Buddhist cultural identity.

Buddhism can be defined, rather paradoxically, as a non-religious religion, an eminently practical ethical-philosophy based on mind cultivation, wisdom and universal compassion. It is an ethico-spiritual value system that prioritises human reason and unaided (i.e., unassisted by any divine or supernatural intervention) escape from suffering through self-realisation. Sri Lanka’s benignly dominant Buddhist socio-cultural background naturally allows unrestricted freedom of religion, belief or non-belief for all its citizens, and makes the country a safe spiritual haven for them. The island’s Buddha Sasana (Dispensation of the Buddha) is the inalienable civilisational treasure that our ancestors of two and a half millennia have bequeathed to us. It is this enduring basis of our identity as a nation which bestows on us the personal and societal benefits of inestimable value mentioned in the AI summary given at the beginning of this essay.

It was this inherent national identity that the Sri Lankan contestant at the 72nd Miss World 2025 pageant held in Hyderabad, India, in May last year, Anudi Gunasekera, proudly showcased before the world, during her initial self-introduction. She started off with a verse from the Dhammapada (a Pali Buddhist text), which she explained as meaning “Refrain from all evil and cultivate good”. She declared, “And I believe that’s my purpose in life”. Anudi also mentioned that Sri Lanka had gone through a lot “from conflicts to natural disasters, pandemics, economic crises….”, adding, “and yet, my people remain hopeful, strong, and resilient….”.

“Ayubowan! I am Anudi Gunasekera from Sri Lanka. It is with immense pride that I represent my Motherland, a nation of resilience, timeless beauty, and a proud history, Sri Lanka.

“I come from Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka’s first capital, and UNESCO World Heritage site, with its history and its legacy of sacred monuments and stupas…….”.

The “inspiring words” that Anudi quoted are from the Dhammapada (Verse 183), which runs, in English translation: “To avoid all evil/To cultivate good/and to cleanse one’s mind -/this is the teaching of the Buddhas”. That verse is so significant because it defines the basic ‘teaching of the Buddhas’ (i.e., Buddha Sasana; this is how Walpole Rahula Thera defines Buddha Sasana in his celebrated introduction to Buddhism ‘What the Buddha Taught’ first published in1959).

Twenty-five year old Anudi Gunasekera is an alumna of the University of Kelaniya, where she earned a bachelor’s degree in International Studies. She is planning to do a Master’s in the same field. Her ambition is to join the foreign service in Sri Lanka. Gen Z’er Anudi is already actively engaged in social service. The Saheli Foundation is her own initiative launched to address period poverty (i.e., lack of access to proper sanitation facilities, hygiene and health education, etc.) especially among women and post-puberty girls of low-income classes in rural and urban Sri Lanka.

Young Anudi is primarily inspired by her patriotic devotion to ‘my Motherland, a nation of resilience, timeless beauty, and a proud history, Sri Lanka’. In post-independence Sri Lanka, thousands of young men and women of her age have constantly dedicated themselves, oftentimes making the supreme sacrifice, motivated by a sense of national identity, by the thought ‘This is our beloved Motherland, these are our beloved people’.

The rescue and recovery of Sri Lanka from the evil aftermath of a decade of subversive ‘Aragalaya’ mayhem is waiting to be achieved, in every sphere of national engagement, including, for example, economics, communications, culture and politics, by the enlightened Anudi Gunasekeras and their male counterparts of the Gen Z, but not by the demented old stragglers lingering in the political arena listening to the unnerving rattle of “Time’s winged chariot hurrying near”, nor by the baila blaring monks at propaganda rallies.

Politically active monks (Buddhist bhikkhus) are only a handful out of the Maha Sangha (the general body of Buddhist bhikkhus) in Sri Lanka, who numbered just over 42,000 in 2024. The vast majority of monks spend their time quietly attending to their monastic duties. Buddhism upholds social and emotional virtues such as universal compassion, empathy, tolerance and forgiveness that protect a society from the evils of tribalism, religious bigotry and death-dealing religious piety.

Not all monks who express or promote political opinions should be censured. I choose to condemn only those few monks who abuse the yellow robe as a shield in their narrow partisan politics. I cannot bring myself to disapprove of the many socially active monks, who are articulating the genuine problems that the Buddha Sasana is facing today. The two bhikkhus who are the most despised monks in the commercial media these days are Galaboda-aththe Gnanasara and Ampitiye Sumanaratana Theras. They have a problem with their mood swings. They have long been whistleblowers trying to raise awareness respectively, about spreading religious fundamentalism, especially, violent Islamic Jihadism, in the country and about the vandalising of the Buddhist archaeological heritage sites of the north and east provinces. The two middle-aged monks (Gnanasara and Sumanaratana) belong to this respectable category. Though they are relentlessly attacked in the social media or hardly given any positive coverage of the service they are doing, they do nothing more than try to persuade the rulers to take appropriate action to resolve those problems while not trespassing on the rights of people of other faiths.

These monks have to rely on lay political leaders to do the needful, without themselves taking part in sectarian politics in the manner of ordinary members of the secular society. Their generally demonised social image is due, in my opinion, to three main reasons among others: 1) spreading misinformation and disinformation about them by those who do not like what they are saying and doing, 2) their own lack of verbal restraint, and 3) their being virtually abandoned to the wolves by the temporal and spiritual authorities.

(To be continued)

By Rohana R. Wasala ✍️

Features

US’ drastic aid cut to UN poses moral challenge to world

‘Adapt, shrink or die’ – thus runs the warning issued by the Trump administration to UN humanitarian agencies with brute insensitivity in the wake of its recent decision to drastically reduce to $2bn its humanitarian aid to the UN system. This is a substantial climb down from the $17bn the US usually provided to the UN for its humanitarian operations.

‘Adapt, shrink or die’ – thus runs the warning issued by the Trump administration to UN humanitarian agencies with brute insensitivity in the wake of its recent decision to drastically reduce to $2bn its humanitarian aid to the UN system. This is a substantial climb down from the $17bn the US usually provided to the UN for its humanitarian operations.

Considering that the US has hitherto been the UN’s biggest aid provider, it need hardly be said that the US decision would pose a daunting challenge to the UN’s humanitarian operations around the world. This would indeed mean that, among other things, people living in poverty and stifling material hardships, in particularly the Southern hemisphere, could dramatically increase. Coming on top of the US decision to bring to an end USAID operations, the poor of the world could be said to have been left to their devices as a consequence of these morally insensitive policy rethinks of the Trump administration.

Earlier, the UN had warned that it would be compelled to reduce its aid programs in the face of ‘the deepest funding cuts ever.’ In fact the UN is on record as requesting the world for $23bn for its 2026 aid operations.

If this UN appeal happens to go unheeded, the possibilities are that the UN would not be in a position to uphold the status it has hitherto held as the world’s foremost humanitarian aid provider. It would not be incorrect to state that a substantial part of the rationale for the UN’s existence could come in for questioning if its humanitarian identity is thus eroded.

Inherent in these developments is a challenge for those sections of the international community that wish to stand up and be counted as humanists and the ‘Conscience of the World.’ A responsibility is cast on them to not only keep the UN system going but to also ensure its increased efficiency as a humanitarian aid provider to particularly the poorest of the poor.

It is unfortunate that the US is increasingly opting for a position of international isolation. Such a policy position was adopted by it in the decades leading to World War Two and the consequences for the world as a result of this policy posture were most disquieting. For instance, it opened the door to the flourishing of dictatorial regimes in the West, such as that led by Adolph Hitler in Germany, which nearly paved the way for the subjugation of a good part of Europe by the Nazis.

If the US had not intervened militarily in the war on the side of the Allies, the West would have faced the distressing prospect of coming under the sway of the Nazis and as a result earned indefinite political and military repression. By entering World War Two the US helped to ward off these bleak outcomes and indeed helped the major democracies of Western Europe to hold their own and thrive against fascism and dictatorial rule.

Republican administrations in the US in particular have not proved the greatest defenders of democratic rule the world over, but by helping to keep the international power balance in favour of democracy and fundamental human rights they could keep under a tight leash fascism and linked anti-democratic forces even in contemporary times. Russia’s invasion and continued occupation of parts of Ukraine reminds us starkly that the democracy versus fascism battle is far from over.

Right now, the US needs to remain on the side of the rest of the West very firmly, lest fascism enjoys another unfettered lease of life through the absence of countervailing and substantial military and political power.

However, by reducing its financial support for the UN and backing away from sustaining its humanitarian programs the world over the US could be laying the ground work for an aggravation of poverty in the South in particular and its accompaniments, such as, political repression, runaway social discontent and anarchy.

What should not go unnoticed by the US is the fact that peace and social stability in the South and the flourishing of the same conditions in the global North are symbiotically linked, although not so apparent at first blush. For instance, if illegal migration from the South to the US is a major problem for the US today, it is because poor countries are not receiving development assistance from the UN system to the required degree. Such deprivation on the part of the South leads to aggravating social discontent in the latter and consequences such as illegal migratory movements from South to North.

Accordingly, it will be in the North’s best interests to ensure that the South is not deprived of sustained development assistance since the latter is an essential condition for social contentment and stable governance, which factors in turn would guard against the emergence of phenomena such as illegal migration.

Meanwhile, democratic sections of the rest of the world in particular need to consider it a matter of conscience to ensure the sustenance and flourishing of the UN system. To be sure, the UN system is considerably flawed but at present it could be called the most equitable and fair among international development organizations and the most far-flung one. Without it world poverty would have proved unmanageable along with the ills that come along with it.

Dehumanizing poverty is an indictment on humanity. It stands to reason that the world community should rally round the UN and ensure its survival lest the abomination which is poverty flourishes. In this undertaking the world needs to stand united. Ambiguities on this score could be self-defeating for the world community.

For example, all groupings of countries that could demonstrate economic muscle need to figure prominently in this initiative. One such grouping is BRICS. Inasmuch as the US and the West should shrug aside Realpolitik considerations in this enterprise, the same goes for organizations such as BRICS.

The arrival at the above international consensus would be greatly facilitated by stepped up dialogue among states on the continued importance of the UN system. Fresh efforts to speed-up UN reform would prove major catalysts in bringing about these positive changes as well. Also requiring to be shunned is the blind pursuit of narrow national interests.

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoGurusinha’s Boxing Day hundred celebrated in Melbourne

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoLeading the Nation’s Connectivity Recovery Amid Unprecedented Challenges

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoIt’s all over for Maxi Rozairo

-

Sports7 days ago

Sports7 days agoTime to close the Dickwella chapter

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoEnvironmentalists warn Sri Lanka’s ecological safeguards are failing

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoDr. Bellana: “I was removed as NHSL Deputy Director for exposing Rs. 900 mn fraud”

-

Opinion3 days ago

Opinion3 days agoRemembering Douglas Devananda on New Year’s Day 2026

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoDons on warpath over alleged undue interference in university governance