Features

More on wrecks and treasure of the sea off Galle

by Somasiri Devendra

(Continued from last week)

Sixty years or so later I was in Galle, organizing an international group of maritime archaeologists who were training a clutch of our young archaeology undergraduates and, at the same time, compiling a data base of shipwrecks in Galle Bay. Among the group was Tom Vosmer, an Australian boat ethnographer, with whom I discussed the Amugoda Oruwa (referred to last week) and the large 100-year old model of a yathra dhoni at Kumarakanda Pirivena, Dodanduwa, that I had been privileged to photo record.

Tom was enthusiastic, for this was the last of a type of large outrigger-equipped sailing ships which could be traced back to the time of Borobudur. Days were spent in examining the model, and measuring, photographing and making detailed drawings of structural details. Built by the young son of a ship-owner, around 1890, it had been awarded a gold medal by the Governor. Tom considered that its accuracy, both in scale and detail, made it a fairly reliable source for documentation.

The drawings and measurements were tested against a computer model for acceptability, and were found to fit in well within the requirements of a vessel of her type. The net result of this was that a complete set of structural drawings was made, and her sailing characteristics determined. Today, gifted by the Ven. Dodanduve Dharmasena, the model is in the Colombo Museum.

Sunken ship’s bell

It was one but the last day of our expedition, and I had stayed behind without going to the diving base. I heard the vehicles returning and Patrick, the expedition’s Australian photographer, ambled up to me and said nonchalantly, “Somasiri, we found something interesting. Like to see it?”

The team was clustered around the van and there was this block of what looked like living coral on the ground. When I bent down to examine it, I suddenly realized that this was not coral but something infinitely richer and stranger. It was a ship’s bell, covered with teeming marine life consisting of bits of coral, colorful anemones, little scuttling crabs and barnacles, but no hint of metal. Only its shape gave the secret of its identity.

We had been diving on the site where a ship had been sunk centuries previously. It was just outside the breakwater. We had known that it was the site where a ship called the Hercules was sunk. It was marked on old charts as “Hercules Kirkopf’ (Kircopf meaning churchyard, graveyard). Mike Wilson (later Swami Sivakalki) and Rodney Jonklass had identified the site in 1956. They did a literary search as well as some diving, discovering quantities of cannon on the seabed.

An eyewitness had described the ship as a first-rate VOC East Indianian, which had been lifted up in a great swell and smashed against rocky Gibbet Island. But there was no further material evidence, and now before me was her bell.

Little by little we cleaned it. The marine creatures were removed, and the barnacles and corals chipped away. Finally, the metal emerged, and with that the letters cast on the bell; partly damaged on top and its clapper missing, it still showed the moulding on top and bottom and the words were clear: Amor vincit omnia anno 1625. “Love conquers all” was a strange motto for an armed merchantman and one that, like the Amugoda Oruwa, was conquered by the unforgiving sea.

More research was done on the Hercules site, where we had located 30 cannons and were to retrieve two sounding leads. Built in Sandam (present Zaandam) in 1655, she was one of two ships of the yacht class, the other being the Achilles. They were about 140 Dutch voet (feet) in length, carrying a crew of 220 each. The Dutch, with their bureaucratic zeal for recording facts, have left several documents on the sinking.

A fleet of four ships, the Thoolen, Angelier, Elburg and Hercules were ready to sail to Batavia and were awaiting fair weather to clear the treacherous entrance to the Bay. Conditions were ideal, with the winds blowing off shore, at six o’clock on the morning of May 22, 1661, and the commander of the city, Isbrand Godsken, had informed Admiral Rijckerslof van Goens. Van Goens had sent him to the Governor, Adriaan van der Meijde who, as it happened was fast asleep. So Godsken made the decision to send the pilot on board. Working quietly, the pilot soon had the Elburg and the Thoolen safely out of the Bay and he went on board the Hercules, while Godsken boarded the Angelier and was witness to the Hercules’ disaster.

While weighing anchor, a crosswind had struck and she had swung around. The anchor rope had caught between the hull and the rudder, making it impossible to control her. She was driven against the rocks and then broke up. She probably had her full complement of 220 on board. We can imagine how many of these lives were lost, and why the site came to be marked on charts as a graveyard. Although the whole cargo of 1,700 packets of fine cinnamon and a consignment of Canarese rice was, lost, the pilot was discharged after a board of inquiry.

The Hercules was but one of several VOC vessels recorded as being lost in Galle Bay, the others being Molen (1658), Dolfijn (1661), Vlissingen (1665-66), Landsman (1679), Gienwens (1776), Barbestijn (1735) and Avondster (1659). Each has a tale of human weakness to tell, but I shall only tell that of the last-named, on whose bones we are diving now.

The Avondster

The Avondster (Evening Star) was in the evening of her life. Originally an English ship, captured by the Dutch and modified, by 1659 she was no longer fit to undertake the arduous trip back to the Netherlands and was used on the inter-Asian trade routes radiating from Batavia. On June 23, 1659, she had taken on board cargo for Negapatnam in India, and was waiting, at her moorings off the Black Fort (Zwaart Bastion) to sail at dawn.

Somehow, the old ship slipped her moorings and started to drift. The boatswain’s mate and the steward went to rouse the skipper, who was asleep below (like the Governor in the case of the Hercules!). The latter came after a quarter of an hour to order that another anchor be dropped, but the ship struck bottom and broke her back. The skipper and mate were less lucky than the pilot of the Hercules, for they were arrested, tried, convicted and ordered to pay for the loss.

The Avondster rested on the seabed for centuries. Alternating monsoons shifted the sand layer above the rocky bottom every year in unwavering rhythm, sometimes covering, sometimes exposing her. Loose artifacts were washed away by the currents rolling over the seabed, to be picked up by local divers and sold in curio shops. Being so close to land, a blanket of silt gradually settled over it, burying and preserving her. Finally, there was no hint of a ship to be seen.

Under early British rule, Galle became less important since the treacherous rocks claimed many a ship, including the steel-hulled steam ships that supplanted the wooden ones. The decision to develop Colombo was taken and Galle became a backwater. In the 1960’s, there was a call to do something about this backwater. An ambitious marine drive was built, followed by a fisheries harbour. Yet Avondster slumbered under the waves.

The new constructions, though, brought about a subtle change in the current flow, forcing it to veer round the new obstacles in their path and seek new routes. Consequently, the Avondster’s shroud of silt gradually began to be eroded and bits of the wreck began to appear. That was when she was shown to us.

We had a dirty site to work on. Most of the time visibility was limited to a few feet or less. There was a sewer emptying into the Bay not far away, and obviously someone was slaughtering chicken and dumping the unwanted bits into the sewer. All around us were floating chicken feet and other unmentionable stuff. Before we had identified the ship, we had already named it “Chicken foot site”!

But it turned out to be one of our most important sites – and we have located 25 others in the Bay.

As archaeologists, our interest was the site itself and the ship, and not in isolated artifacts. But some of the latter bring the past vividly to life. Such items include remains of the ship’s galley (kitchen) built of brick and lead sheeting, coils and coils of the rope and cordage which were so essential on board sailing ships, pulley-blocks and other ship’s accessories, wine bottles of the period, contents of the medicine cupboard (one jar contains mercury, then used to combat syphilis), ivory combs, parts of a gun carriage, earthenware jars and fragments of ceramic wares.

A combination of materials from east and west, namely Chinese, Dutch and South-East Asian is also interesting. From the perspective of nautical archaeology, the details of her hull construction and planking are giving us new information. The work still goes on and this site will, some day, become one of Sri Lanka’s major attractions.

Hindu icon and other finds

Under the waters of Galle we found more than Dutch shipwrecks. Among other discoveries was a Hindu icon with, strangely, the Roman numerals “XIV” scratched upon it, possibly the catalogue number of a collection. From its location, which was a 19th century mooring, it may have been part of a collection of antiques that was being shipped out of the country by ship, but which had fallen overboard in loading from boat to ship.

Perhaps its owner was Sir Alexander Johnston, Chief Justice. We know that he admits to having shipped out an invaluable collection on board the East Indianian Lady Jane Dundas, which sank in 1809 before reaching England. Galle was the premier port then and it is likely that this is the only artifact of that collection that did not leave Sri Lankan waters. This ship, on March 14, 1809, in company with fellow East Indiamen Calcutta, Bengal and Jane, Duchess of Gordon detached from the rest of the ships in convoy at Mauritius and was never heard of again.

Near the same location, we found several pieces of, and one complete 820 kg Arab-Indian stone anchor, complete with wooden fittings. This type is common in many Arabian Sea locations but this so far is the farthest east one has been found. The wooden pieces helped us to date it to 1310-1640, making it the oldest artifact to have been found in Galle, on land or sea. The stone itself was identified as of Omanese origin.

At the same anchorage were other types of anchor, including one of the so-called Mediterranean types, but unfortunately one cannot date stone and so we have no idea of its age. Recently, fishermen at Godawaya, another ancient port south of Galle, found another of that type pointing again to the possibility of Roman ships voyaging round the island on their way to the Coromandel coast of India. Large hoards of Roman coins and trade goods along the Ruhuna coast support this.

Again there is a Sung dynasty ceramic bowl, almost identical with the one found in Yapahuwa, with only a small chip missing and found by itself. Zheng-He (Chengho) touched at Galle and set up his now famous tri-lingual inscription in 1410 or so. Could it have been from one of his ships, or may be it fell off any one of the ships that called at Galle on their east-west trading voyages. Truly, many are the surprises the seas can spring on us.

(To be continued)

(Excerpted from Jungle Journeys in Sri Lanka edited by CG Uragoda)

Features

Thousands celebrate a chief who will only rule for eight years

Thousands of people have been gathering in southern Ethiopia for one of the country’s biggest cultural events.

The week-long Gada ceremony, which ended on Sunday, sees the official transfer of power from one customary ruler to his successor – something that happens every eight years.

The tradition of regularly appointing a new Abbaa Gadaa has been practised by the Borana community for centuries – and sees them gather at the rural site of Arda Jila Badhasa, near the Ethiopian town of Arero.

It is a time to celebrate their special form of democracy as well as their cultural heritage, with each age group taking the opportunity to wear their different traditional outfits.

These are paraded the day before the official handover during a procession when married women march with wooden batons, called “siinqee”.

[BBC]

The batons have symbolic values of protection for women, who use them during conflict.

If a siinqee stick is placed on the ground by a married woman between two quarrelling parties, it means the conflict must stop immediately out of respect.

During the procession, younger women lead at the front, distinguished from the married women by the different colour of their clothing.

[BBC]

In this pastoralist society women are excluded from holding the top power of Abbaa Gadaa, sitting on the council of elders or being initiated into the system as a child.

But their important role can be seen during the festival as they build all the accommodation for those staying for the week – and prepare all the food.

And the unique Gada system of governance, which was added to the UN’s cultural heritage list in 2016, allows for them to attend regular community meetings and to voice their opinions to the Abbaa Gadaa.

Gada membership is only open to boys whose fathers are already members – young initiates have their heads shaven at the crown to make their rank clear.

The smaller the circle, the older he is.

As the global cultural body UNESCO reports, oral historians teach young initiates about “history, laws, rituals, time reckoning, cosmology, myths, rules of conduct, and the function of the Gada system”.

Training for boys begins as young as eight years old. Later, they will be assessed for their potential as future leaders.

As they grow up, tests include walking long distances barefoot, slaughtering cattle efficiently and showing kindness to fellow initiates.

Headpieces made from cowrie shells are traditionally worn by young trainees. The only other people allowed to wear them are elderly women.

Both groups are revered by Borana community members.

Men aged between 28 and 32 are identified by the ostrich feathers they wear, which are known in the Afaan Oromo language as “baalli”.

Their attendance at the Gada ceremony is an opportunity to learn, prepare and bond as it is already known who the Abbaa Gadaa from this age group will be taking power in 2033.

The main event at the recent Gada ceremony was the handover of power, from the outgoing 48-year-old Abbaa Gadaa to his younger successor.

Well-wishers crossed the border from Kenya and others travelled from as far as Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa, to witness the spectacle. The governor of Kenya’s Marsabit county was among the honoured guests.

Thirty-seven-year-old Guyo Boru Guyo, seen here holding a spear, was chosen to lead because he impressed the council of elders during his teenage years.

[BBC]

He becomes the 72nd Abbaa Gadaa and will now oversee the Borana community across borders – in southern Ethiopia and north-western Kenya.

As their top diplomat, he will also be responsible for solving feuds that rear their heads for pastoralists. These often involve cattle raiding and disputes over access to water in this drought-prone region.

During his eight years at the helm, his successor will finish his training to take on the job in continuation of this generations-old tradition.

[BBC]

Features

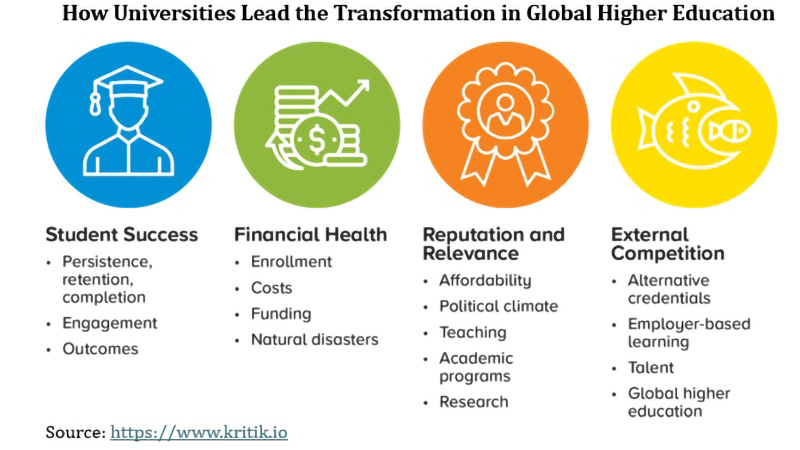

How universities lead transformation in global higher education

To establish a high-quality educational institution, it is essential to create a sustainable and flexible foundation that meets contemporary educational needs while adapting to future demands. The following outline a robust model for a successful and reputable educational institution. (See Image 1 and Graphs 1 and 2)

To establish a high-quality educational institution, it is essential to create a sustainable and flexible foundation that meets contemporary educational needs while adapting to future demands. The following outline a robust model for a successful and reputable educational institution. (See Image 1 and Graphs 1 and 2)

Faculty Excellence and Research Integration: Recruit faculty members with advanced qualifications, industry experience, and a strong commitment to student development. Integrate research as a cornerstone of teaching to encourage innovation, critical inquiry, and evidence-based learning. Establish dedicated research groups and facilities, fostering a vibrant research culture, led by senior academics, and providing hands-on research experience for students.

Infrastructure and Learning Environment: Develop modern, accessible campuses that accommodate diverse learning needs and provide a conducive environment for academic and extracurricular activities. Invest in state-of-the-art facilities, including libraries, laboratories, collaborative workspaces, and recreational areas to support well-rounded student development. Utilize technology-enhanced classrooms and virtual learning platforms to create dynamic and interactive learning experiences.

Global Partnerships and Multicultural Environment: Promote partnerships with reputable international universities and organizations to provide global exposure and collaborative opportunities. Encourage student and faculty exchange programmes, joint research, and international internships, broadening perspectives and building cross-cultural competencies. Cultivate a multicultural campus environment that embraces diversity and prepares students to thrive in a globalized workforce.

Industry Engagement and Graduate Employability: Collaborate closely with industry partners to ensure that programmes meet professional standards and graduates possess relevant, in-demand skills. Embed practical experiences, such as internships and work placements, within the academic curriculum, to enhance employability. Establish a dedicated career services team to support job placement, career counselling, and networking opportunities, maintaining high graduate employment rates.

Student-Centric Support Systems and Life Skills: Offer comprehensive student support services, including academic advising, mental health resources, and career development programmes. Provide opportunities for students to develop essential life skills such as teamwork, leadership, communication, and resilience. Promote a balanced academic and social life by fostering clubs, sports, and recreational activities that contribute to personal growth and community engagement.

Commitment to Sustainability and Social Responsibility: Integrate sustainability into campus operations and curricula, preparing students to lead in a sustainable future. Encourage social responsibility through community engagement, service-learning projects, and ethical research initiatives. Implement eco-friendly practices across campus, from energy-efficient buildings to waste reduction, promoting environmental awareness.

Governance, Independence, and Financial Sustainability: Establish transparent, ethical governance structures that promote accountability, inclusivity, and long-term planning. Strive for financial independence by building a sustainable revenue model that balances tuition, grants, partnerships, and philanthropic contributions. Prioritize flexibility in governance to adapt quickly to external changes while safeguarding institutional autonomy.

By emphasizing quality, inclusivity, innovation, and adaptability, an educational institution can cultivate a culture of academic excellence and social responsibility, producing well-rounded graduates who are equipped to succeed and contribute meaningfully to society. This framework provides a strategic approach to building an institution that thrives academically, socially, and economically.

Critique of the Traditional Sri Lankan University System

Outdated Curriculum and Lack of Industry Relevance: Many traditional universities in Sri Lanka operate with rigid curricula that are slow to adapt to rapidly changing industry needs, leaving graduates underprepared for the global workforce. Syllabi are often centered around theoretical knowledge with limited focus on practical, hands-on experience, problem-solving, and critical thinking skills.

Outdated Curriculum and Lack of Industry Relevance: Many traditional universities in Sri Lanka operate with rigid curricula that are slow to adapt to rapidly changing industry needs, leaving graduates underprepared for the global workforce. Syllabi are often centered around theoretical knowledge with limited focus on practical, hands-on experience, problem-solving, and critical thinking skills.

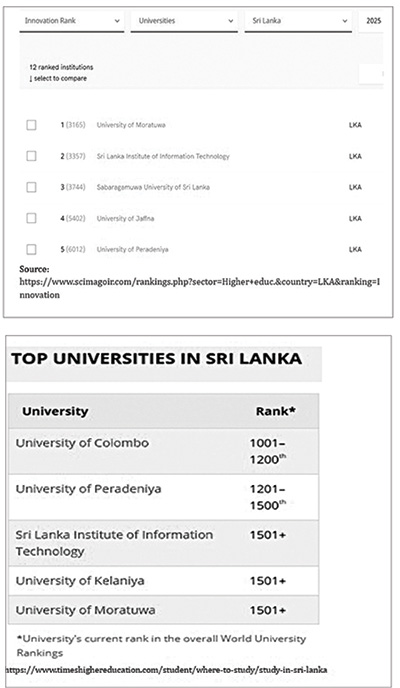

Insufficient Research and Innovation Focus: The Sri Lankan university system places minimal emphasis on research, innovation, and practical application, which hinders the development of a strong research culture. Limited funding, resources, and incentives for faculty and students to pursue cutting-edge research reduce international visibility and publications, key factors in global rankings.

Lack of International Partnerships and Exposure: Traditional universities have minimal collaboration with foreign institutions, limiting opportunities for student exchange programmes, collaborative research, and global internships. This lack of exposure restricts students’ cultural awareness, adaptability, and networking skills, which are essential in today’s globalized economy.

Bureaucratic Governance and Inflexibility: Highly centralized and bureaucratic governance structures result in slow decision-making, stifling innovation and responsiveness to changing educational demands. Universities face significant limitations in introducing new programmes, hiring qualified faculty, and allocating resources, which affects their competitive edge and ability to adapt.

Underfunded Infrastructure and Resources: The lack of adequate funding for state-of-the-art infrastructure, technological resources, and modern learning spaces reduces the quality of education and student experience. Insufficient investment in libraries, laboratories, and virtual learning tools limits access to essential resources needed to build research capabilities and attract international students.

Limited Emphasis on Student-Centric Support Services: Support services such as career counselling, academic advising, and mental health resources are insufficiently developed in many institutions, impacting students’ overall well-being and employability. Universities often lack the means to prepare students for the workforce beyond academics, which results in graduates with high academic knowledge but limited job-ready skills.

Recommended Transformations for World-Class Standards

Curriculum Revamp with a Focus on Industry Relevance: Shift towards an interdisciplinary, outcome-based curriculum that aligns with industry requirements and promotes experiential learning. Establish partnerships with industries to incorporate internships, co-ops, and project-based learning, providing students with practical skills. Incorporate modules on critical thinking, problem-solving, and digital literacy, which are essential for employability and adaptability.

Enhancing Research Capacity and Innovation Ecosystem: Allocate dedicated funding for research and establish incentives for faculty and students to publish in high-impact journals. Develop specialized research centres and labs focusing on areas critical to national and global challenges, such as technology, sustainable development, and public health. Foster innovation hubs, incubators, and accelerators, within universities, to support entrepreneurship and collaboration with the private sector, driving societal impact and ranking potential.

International Partnerships and Global Exposure: Form alliances with reputable international universities to offer dual degrees, joint research programmes, and student and faculty exchange opportunities. Encourage academic collaborations that enable students to work on global projects, thereby enhancing cultural competence and preparing them for international careers. Create virtual exchange programmes and international seminars to engage students in global conversations without extensive travel requirements.

Autonomous and Responsive Governance: Decentralize governance to allow universities to make independent decisions on programmes, faculty hiring, and funding allocation, fostering flexibility and responsiveness. Implement performance-based accountability systems for university administrators, rewarding institutions that achieve excellence in teaching, research, and innovation. Empower universities to secure alternate funding sources through grants, industry partnerships, and philanthropic contributions, ensuring financial stability and academic independence.

Investment in Infrastructure and Digital Transformation: Prioritize investment in modern campus facilities, advanced laboratories, and digital learning environments to provide students with a high-quality academic experience. Expand access to online learning resources, digital libraries, and virtual classrooms, offering students a more adaptable, blended learning model. Create dedicated spaces for collaborative learning and interdisciplinary activities, fostering a culture of innovation and teamwork.

Robust Student-Centric Support Systems: Establish comprehensive support services, including career development, mental health resources, and academic advising, to help students navigate both academic and personal challenges. Introduce career-oriented training programmes focusing on employability skills, including communication, networking, and leadership, to prepare students for the workforce. Develop alumni networks and mentorship programmes, connecting students with successful graduates for career guidance and networking opportunities.

Emphasis on Sustainability and Social Responsibility: Embed sustainability principles in campus operations, curricula, and research activities to align with global priorities and contribute to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Initiate community engagement programmes that encourage students to apply their knowledge in real-world settings, fostering social responsibility and regional development. Encourage environmental initiatives, like waste reduction, energy efficiency, and green campus policies, reflecting a commitment to global best practices.

By adopting these strategies, traditional Sri Lankan universities can transform into competitive, globally recognized institutions. This shift would enable them to improve international rankings, increase graduate employability, attract a diverse student body, and contribute meaningfully to both the local and global knowledge economies.

The traditional university system in Sri Lanka, while rich in history and academic legacy, faces significant challenges in meeting the demands of the modern, globally connected world. The system requires critical reforms to enhance its alignment with international standards, improve rankings, and produce graduates ready for today’s dynamic job market. This essay discusses the shortcomings of the existing system and provides actionable recommendations to enable Sri Lankan universities to transform into globally competitive, high-ranking institutions.

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT University, Malabe. He is also the author of the “Doing Social Research and Publishing Results”, a Springer publication (Singapore), and “Samaja Gaveshakaya (in Sinhala). The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the institution he works for. He can be contacted at saliya.a@slit.lk and www.researcher.com)

Features

Govt. needs to explain its slow pace

by Jehan Perera

It was three years ago that the Aragalaya people’s movement in Sri Lanka hit the international headlines. The world watched a celebration of democracy on the streets of Colombo as tens of thousands of people of all ages and communities gathered to demand a change of government. The Aragalaya showed that people have the power, and agency, to make governments at the time of elections and also break governments on the streets through non-violent mass protest. This is a very powerful message that other countries in the region, particularly Bangladesh and Pakistan in the South Asian region, have taken to heart from the example of Sri Lanka’s Aragalaya. It calls for adopting ‘systems thinking’ in which there is understanding of the interconnectedness of complex issues and working across different sectors and levels that address root causes rather than just the symptoms.

Democracy means that power is with the people and they do not surrender it to the government to become inert and let the government do as it wants, especially if it is harming the national interest. This also calls for collaboration across sectors, including political parties, businesses, NGOs and community groups, to create a collective effort towards change as it did during the Aragalaya. The government that the Aragalaya protest movement overthrew through street power was one that had been elected by a massive 2/3 majority that was unprecedented in the country under the proportional electoral system. It also had more than three years of its term remaining. But when it became clear that it was jeopardizing the national interest rather than furthering it, and inflicted calamitous economic collapse, the people’s power became unstoppable.

A similar situation arose in Bangladesh, a year ago, when the government of Sheikh Hasina decided to have a quota that favoured her ruling party’s supporters in the provision of scarce government jobs to the people. In the midst of economic hardship, this became a provocation to the people of Bangladesh. They saw the corruption and sense of entitlement in those who were ruling the country, just as the Sri Lankan people had seen in their own country two years earlier. This policy sparked massive student-led protests, with young people taking to the streets to demand equitable opportunities and an end to nepotistic practices. They followed the Sri Lankan example that they had seen on the television and social media to overthrow a government that had won the last election but was not delivering the results it had promised.

CONSTITUTIONAL PROCESS

Despite similarities, there are also major differences between Bangladesh and Sri Lankan uprisings. In Sri Lanka, the protest movement achieved its task with only a minimal loss of life. In Bangladesh, the people mobilized against the government which had become like a dictatorship and which used a high level of violence in trying to suppress the protests. In Sri Lanka, the transition process was the constitutionally mandated one and also took place non-violently. When President Gotabaya Rajapaksa resigned, Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe succeeded him as the acting President, pending a vote in Parliament which he won. President Wickremesinghe selected his Cabinet of Ministers and governed until his presidential term ended. A new President Anura Kumara Dissanayake was elected at the presidential elections which were the most peaceful elections in the country’s history.

In Bangladesh, the fleeing abroad of Prime Minister Hasina was not followed by Parliament electing a new Prime Minister. Instead, the President of Bangladesh Mohammed Shahabuddin appointed an interim government, headed by NGO leader Muhammad Yunus. The question in Bangladesh is how long will this interim government continue to govern the country without elections. The mainstream political parties, including that of the deposed Prime Minister, are calling for early elections. However, the leaders of the protest movement that overthrew the government on the streets and who experienced a high level of violence do not wish elections to be held at this time. They call for a transitional justice process in which the truth of what happened is ascertained and those who used violence against the people are held accountable.

By way of contrast, in Sri Lanka, which went through a legal and constitutional process to achieve its change of government there is little or no demand for transitional justice processes against those who held office at the time of the Aragalaya protests. Even those against whom there are allegations of human rights violations and corruptions are permitted to freely contest the elections. But they were thoroughly defeated and the people elected a new NPP government with a 2/3 majority in Parliament, many of whom are new to politics and have no association with those who governed the country in the past. This is both a strength and a weakness. It is a strength in that the members of the new government are idealistic and sincere in their efforts to improve the life of the people. But their present non-consultative and self-reliant approach can lead to erroneous decisions, such as to centrally appoint a majority of council members, who are of Sinhalese ethnicity, to the Eastern University which has a majority of Tamil faculty and students.

UNRESOLVED PROBLEMS

The problem for the new government is that they inherited a country with massive unresolved problems, including the unresolved ethnic conflict which requires both sensitivity and consultations to resolve. The most pressing problem, by any measure, is the economic problem in which 25 percent of the population have fallen below the poverty line, which is double the percentage that existed three years ago. Despite the appearance of high-end consumer spending, the gap between the rich and poor has increased significantly. The day-to-day life of most people is how to survive economically. The former government put the main burden of repaying the foreign debts and balancing the budget on the poorer sections of the population while sparing those at the upper end, who are expected to be engines of the economy. The new government has to change this inequity but it has little leeway to do so, because the government’s treasury has been emptied by the misdeeds of the past.

Despite having a 2/3 majority in Parliament, the government is hamstrung by its lack of economic resources and the recalcitrance of the prevailing system that continues to be steeped in the ways of the past. President Dissanayake has been forthright about this when he addressed Parliament during the budget debate. He said, “the country has been transformed into a shadow criminal state. While we see a functioning police force, military, political authority and judiciary on the surface, beneath this structure exists an armed underworld with ties to law enforcement, security forces and legal professionals. This shadow state must be dismantled. There are two approaches to dealing with this issue: either aligning with the criminal underworld or decisively eliminating it. Unlike previous administrations, which coexisted with organized crime, the NPP-led government is determined to eradicate it entirely.”

Sri Lanka’s new government has committed to holding local government elections within two months unlike Bangladesh’s protest leaders, who demand that transitional justice and accountability for past crimes take precedence over elections. This decision aligns with constitutional mandates and upholds a Supreme Court ruling that the previous government had ignored. However, holding elections so soon after a major political shift poses risks. The new government has yet to deliver on key promises—bringing economic relief to struggling families and prosecuting those responsible for corruption. It needs to also address burning ethnic and religious grievances, such as the building of Buddhist religious sites where there are no members of that community living there. If voters lose patience, political instability could return. The people need to be farsighted when they make their decision to vote. As citizens they need to recognise that systemic change takes time.

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoPrivate tuition, etc., for O/L students suspended until the end of exam

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoShyam Selvadurai and his exploration of Yasodhara’s story

-

Editorial7 days ago

Editorial7 days agoCooking oil frauds

-

Editorial4 days ago

Editorial4 days agoRanil roasted in London

-

Latest News4 days ago

Latest News4 days agoS. Thomas’ beat Royal by five wickets in the 146th Battle of the Blues

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoTeachers’ union calls for action against late-night WhatsApp homework

-

Sports7 days ago

Sports7 days agoRoyal favourites at the 146th Battle of the Blues

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoHeroes and villains