Features

More on leopards, two beautiful plains and camping in the wild

by Walter R. Gooneratne

(continued from last week)

As this would be our last day, we decided to trek to two fabulous places as described by Babun. There were two large plains called Waraketiya and Dananayake Eliya. They were about six miles from camp towards Muduntalawa. The track was again riddled with fresh pug marks of leopard, but no animals were seen. As it was still drizzling, they were probably taking cover in the jungle.

After about two hours of walking, we came to Waraketiya Eliya (eliya =plain). It was a large plain about 200 yards wide and bounded by two streams, Kumbukpitia Ara on the west and Suandandan Ara on the east. While walking through the swampy plain we surprised a herd of wild buffaloes wallowing in a mud hole. Fortunately, they bolted in panic on seeing us. Except for a few peafowl, no animals were seen in the plain. The two streams coalesced to form the Dharage Ara. We followed this stream for some distance and came upon Dananayake plain, which was much larger than Waraketiya Eliya.

An elephant was browsing on the branches of a tree. We watched it for a little while and then made a detour downwind. We then went on to explore the vast plain. In a water-hole, a large sounder of wild boar, accompanied by numerous sucklings was feeding on the yams of lotus, so dear to them. Wild boar flesh was what we wanted to take back home, and here was our chance. They ignored us and continued to feed, while Babun and Pervey were debating on which was the fattest. Having made his choice, Pervey fired on a big fat boar with his rifle. At the shot, the whole sounder took flight, including the targeted animal.

I thought he had missed it and was about to fire again, when he collapsed and died a short distance away. We now regretted our decision not to bring the jeep as we would now have to carry the heavy burden ourselves, The pig was cut into two and each half slung on a pole. Pervey and Babun took one half, and Mackie and I the other. As young doctors, our funds were limited; hence the sparing use of the jeep.

As we were returning, a short distance from Waraketiya, some monkeys were calling to our right. Babun said they were calling on account of a leopard, and wanted me to come with him. Glad to be relieved of my burden even for a short while, I dropped the carcass and followed him. A huge bear was ambling towards us. I fired at him with the rifle and unfortunately hit him in the middle of his spine.. His hind limbs were paralysed and he came crawling on his forelimbs, yelling blue murder. My rifle had two triggers. The rear one had to be squeezed first to activate the front or hair trigger. In my excitement I had squeezed the front trigger and the bullet ploughed harmlessly into the ground. My magazine was now empty. Fortunately, Pervey came running up and gave the wounded animal the coup-de-grace. It was a huge male bear.

As it would be impossible to carry both carcasses, to my immediate relief it was decided to go back to camp, refresh ourselves with a bath and lunch, and bring the jeep to take the prizes home. We hoped no marauding leopard would deprive us of our pork before we came back. When we arrived in camp, the cook was missing, and the food had not been cooked, We were worried if any mishap had befallen him. When we called him, he sheepishly answered from the top of a nearby tree. He himself did not know how he was able to shin up the tree, as he had much difficulty in coming down even with our help. He explained what had happened.

Shortly after we left, he had set about preparing our midday meal with his back to the track. Suddenly there was a blood curdling sound from behind. At first he had thought it was a devil bird, but on turning round he saw the devil himself in the form of a bear screaming obscenities (as described by him) and tearing away into the jungle in the opposite direction. The next thing he knew was that he found himself up the tree. What had happened was that the bear had come ambling down the track and accidentally trod on the embers of the previous night’s camp-fire.

After lunch we took the jeep and brought back the carcasses, which fortunately were untouched.

Our last evening was spent with Babun skinning the bear and Mackie taking a rest. Pervey and I walked to Thalakola Wewa, but saw nothing to interest us. The next day we bade farewell to our new-found friend, Babun and returned to Kandy about 10 that night. The first person to greet us the next morning was old Seetin Singho. He, like Shylock, had come for his pound of kara mus, which he received with much glee.

In those days, there was a visitor’s book kept at the park office at Yala, where those who entered its precincts wrote their comments. My entry in the visitor’s book about this trip was displayed about a couple of years ago in the museum at the Park office. Later it was replaced by the entries of a similar trip by the Hon. D.S.Senanayake and his party, which if I remember right, included the late Mr. Sam Elapata. On inquiry from the park officials, I was informed that they were unable to trace my entry.

Leopard at Kumana

For quite sometime I had been contemplating visiting Kumana as I had heard so much about its famed bird sanctuary, enormous herds of deer and other attractions. My usual companions, Pervey Lawrence and Mackie Ratwatte were not free to join me when the opportunity came quite unexpectedly when my friend, the late Dr. Ivor Obeysekera suggested that we make a trip to Kumana. Of course I jumped at it.

The party consisted of Ivor, his wife, my wife Nirmalene and myself. At 3.30 am on April 12, 1956 we left Kandy in an old Willys jeep and a trailer that Ivor had borrowed from a friend. We had obtained permits from the Department of Wildlife (as it was then called) to shoot peafowl, jungle fowl, deer and leopard. Ivor had not used a gun before and did not own one. I had with me my usual armoury of weapons, namely a 7.9 mm Mauser, a Webley, Scott double-barrel shot gun and .22 calibre Hornet.

Bellowing crocodiles

In those days there was very little traffic, specially at that hour, and the roads were well maintained. After a pleasant drive we arrived in Batticaloa about 8 am for breakfast at my brother’s home. After a sumptuous meal we left for Pottuvil and Kumana on the coastal road. The next stop was just past Komari in the shade of a huge mara tree for a packeted lunch provided by my brother. About ten yards from where we were, was a culvert, and suddenly there came a loud booming sound from its direction. We were at a loss to realize what it could be. I had not heard anything like this before. I picked up my rifle and walked cautiously to investigate. I was stunned by what I saw. There, lying in the shallow water was a medium-sized crocodile bellowing away. As it was half submerged, bubbles of air billowed out of the sides of its mouth. I beckoned to the others to come up, but as soon as they peeped over, the creature saw us and crept into the culvert.

This is the first time I had heard this sound. I heard this call once more when going down the Mahaweli in the company of Mr. Thilo Hoffman and a few others. At one point we found a nest of baby crocodiles, probably a day or two old. One of our party picked up a few of them in his folded shirt. Their squealing alerted the mother who came charging through the water from nearby. He dropped the hatchlings and bolted for dear life. The mother then came up to the nest and sent out her bellowing call warning all and sundry to keep away from her family. We did not waste much time on the way and traveled through Pottuvil and Panama. At Halawa we saw an elephant feeding some distance from the road and left him undisturbed.

Old warriors

We arrived at Okanda without further incident and met the ranger, Peter Jayawardene for the first time. This was the beginning of a lifelong friendship with a most colourful character. The legendry Garuwa was to be our guide and tracker. He had as his assistant Wasthuwa, an equally experienced jungle man. As it was getting late, Garuwa decided that we camp for the night at Itikala Kalapuwa. At that time of the evening, the surface of the kalapuwa or lagoon glistened like a sheet of molten silver. Putting up camp was a simple affair. A rope was tied between two trees and a tarpaulin slung over it and the four corners tethered to convenient trees. Four camp beds completed the five-star comfort.

All the day’s fatigue and grime were washed away in the cool water of the nearby kema or rock water-hole. After a stiff sundowner, we were treated to a delicious dinner of rice, pol sambol, which is a mixture of mainly chilli powder and coconut scrapings, homemade ambulthial, which is a traditional fish curry and dhal or lentil curry prepared by the wives, ably assisted by Wasthuwa.

Bait for the leopard

As Garuwa was keen that we shoot an animal as bait for leopard, as well as for the pot, we left camp at about 6 am. He suggested that we walk, since the jeep would disturb the animals. The wives insisted on accompanying us. We walked till about 7.30 and the sun was getting uncomfortably hot, but we had not seen any worthwhile animal except a lone elephant in the distance. I suggested that we go back to camp, have breakfast and go for a drive by jeep. However, Garuwa said that there was a good water-hole fairly close by and it may be worth checking.

A good 10 minutes’ walk brought us to a circular muddy pond about 40 yards in diameter. Peeping through the foliage, we saw a large sambhur stag wallowing in the mud. It died immediately it was shot, and as we had to bring the jeep and trailer to take back the carcass, I volunteered to walk back with Wasthuwa and bring these.

When we came back, Garuwa suggested that we go back to the village and pick up a young lad who could cook, thus relieving the ladies from that chore. This turned out to be a real blessing. He was a young man of about 20 years, and not only was he an excellent cook but also a very willing and efficient worker. We nicknamed him Kadisara, meaning quick-acting.

After breakfast, the carcass was divided in two. The head and the upper part of the thorax, which were to be the leopard bait, were tied to the jeep and dragged to the site where it was to be secured. A prowling leopard had a better chance of spotting the drag mark and finding the kill. The site for the bait was at a point about 20 yards down the track leading to the Kumana tank, on the edge of the forest. This area was open country, but about 30 yards further down, the road ended in high forest.

It was earlier decided to move camp to the regular site on the banks of Kumbukkan Oya, but as it was too sunny, we decided to postpone the operation for the cool of the evening. As it was now about 11 am, Garuwa suggested that we catch some crabs to add variety to our lunch. He cut a stake about three feet long and sharpened it to a point at one end. He then took us to Itikala Kalapuwa. Having alighted from the vehicle, he asked me to come with him to the water of the lagoon, which was only about a foot deep near the edge. Peering into the water, he showed me a crab and spiked it with the stake. Seven crabs were thus captured.

Having come back to the camp, we had a bath in the kema and rounded off with a glass of ice-cold beer. In no time Kadisara prepared a delicious lunch with venison and crab curry. As there was no murunga in the jungle, he picked up some leaves from the kara plant, if I remember right, to flavour the crab curry. A well earned siesta was taken before the evening’s chores.

Camp was soon dismantled, the jeep and trailer were loaded and we were on our way to the new camp site, which we reached at about 5 pm. What a beautiful spot it was. There was a wide expanse of river before us with its banks lined with lofty kumbuk trees, which spread their canopy over us like a giant umbrella.

(Excerpted from Jungle Journeys in Sri Lanka Experiences and encounters Edited by CG Uragoda)

Features

Pharmaceuticals, deaths, and work ethics

Yet again, deaths caused by questionable quality pharmaceuticals are in the news. As someone who had worked in this industry for decades, it is painful to see the way Sri Lankans must face this tragedy repeatedly when standard methods for avoiding them are readily available. An article appeared in this paper (Island 2025/12/31) explaining in detail the technicalities involved in safeguarding the nation’s pharmaceutical supply. However, having dealt with both Western and non-Western players of pharmaceutical supply chains, I see a challenge that is beyond the technicalities: the human aspect.

There are global and regional bodies that approve pharmaceutical drugs for human use. The Food and Drug Administration (USA), European Medicines Agency (Europe), Medicine and Health Products Regulatory Agency (United Kingdom), and the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (Japan) are the major ones. In addition, most countries have their own regulatory bodies, and the functions of all such bodies are harmonized by the International Council for Harmonization (ICH) and World Health Organization (WHO). We Sri Lankan can take solace in knowing that FDA, the premier drug approval body, came into being in 1906 because of tragedies similar to our own. Following the Elixir Sulfanilamide tragedy that resulted in over one hundred deaths in 1938 and the well-known Phthalidomide disaster in 1962, the role and authority of FDA has increased to ensure the safety and efficacy of the US drug supply.

Getting approval for a new proprietary pharmaceutical is an expensive and time-consuming affair: it can take many billions of dollars and ten to fifteen years to discover the drug and complete all the necessary testing to prove safety and efficacy (Island 2025/01/6). The proprietary drugs are protected by patents up to twenty years, after which anyone with the technical knowhow and capabilities can manufacture the drug, call generics, and seek approval for marketing in countries of their choice. This is when the troubles begin.

Not having to spend billions on discovery and testing, generics manufactures can provide drugs at considerable cost savings. Not only low-income countries, but even industrial countries use generics for obvious reasons, but they have rigorous quality control measures to ensure efficacy and safety. On the other hand, low-income countries and countries with corrupt regulatory systems that do not have reasonable quality control methods in place become victims of generic drug manufacturers marketing substandard drugs. According to a report, 13% of the drugs sold in low-income countries are substandard and they incur $200 billion in economic losses every year (jamanetworkopen.2018). Sri Lankans have more reasons to be worried as we have a history of colluding with scrupulous drug manufactures and looting public funds with impunity; recall the immunoglobulin saga two years ago.

The manufacturing process, storage and handling, and the required testing are established at the time of approval; and they cannot be changed without the regulatory agency’s approval. Now a days, most of the methods are automated. The instruments are maintained, operated, and reagents are handled according to standard operating procedures. The analysts are trained and all operations are conducted in well maintained laboratories under current Good Manufacturing Procedures (cGMP). If something goes wrong, there is a standard procedure to manage it. There is no need for guess work; everything is done following standard protocols. There is traceability; if something went wrong, it is possible to identify where, when, and why it happened.

Setting up a modern analytical laboratory is expensive, but it may not cost as much as a new harbor, airport, or even a few kilometers of new highway. It is safe to assume that some private sector organizations may already have a couple of them running. Affordability may not be a problem. But it is sad to say that in our part of the world, there is a culture of bungling up the best designed system. This is a major concern that Western pharmaceutical companies and regulatory agencies have in incorporating supply chains or services from our part of the world.

There are two factors that foster this lack of work ethics: corruption and lack of accountability. Admirably, the private sector has overcome this hurdle for the most part, but in the public sector, from top to bottom, lack of accountability and corruption have become a pestering cancer debilitating the economy and progress. Enough has been said about corruption, and fortunately, the present government is making an effort to curb it. We must give them some time as only the government has changed, not the people.

On the other hand, lack of accountability is a totally alien concept for our society. In many countries, politicians are held accountable at elections. We give them short breaks, to be re-elected at the next election, often with super majorities, no matter how disastrous their actions were. When it comes to government servants, we have absolutely no way to hold them accountable. There is absolutely no mechanism in place; it appears that we never thought about it.

Lack of accountability refers to the failure to hold individuals responsible for their actions. This absence of accountability fosters a culture of impunity, where corrupt practices can thrive without fear of repercussions. In Sri Lanka, a government job means a lifetime employment. There is no performance evaluation system; promotions and pay increases are built in and automatically implemented irrespective of the employee’s performance or productivity. The worst one can expect for lapses in performance is a transfer, where one can continue as usual. There is no remediation. To make things worse, often the hiring is done for political reasons rather than on merit. Such employees have free rein and have no regard for job responsibilities. Their managers or supervisors cannot take actions as they have their political masters to protect them.

The consequences of lack of accountability in any area at any level are profound. There is no need to go into detail; it is not hard to see that all our ills are the results of the culture of lack of accountability, and the resulting poor work ethics. Not only in the pharmaceuticals arena, but this also impacts all aspects of products and services available. If anyone has any doubts, they should listen to COPE committee meetings. Without a mechanism to hold politicians, government employees, and bureaucrats accountable for their actions or lack of it, Sri Lanka will continue to be a developing country forever, as has happened over the last seventy years. As a society, we must take collective actions to demand transparency, hold all those in public service accountable, and ensure that nation’s resources are used for the benefit of all citizens. The role of ethical and responsible journalism in this respect should not be underestimated.

by Geewananda Gunawardana, Ph.D. ✍️

Features

Tips for great sleep

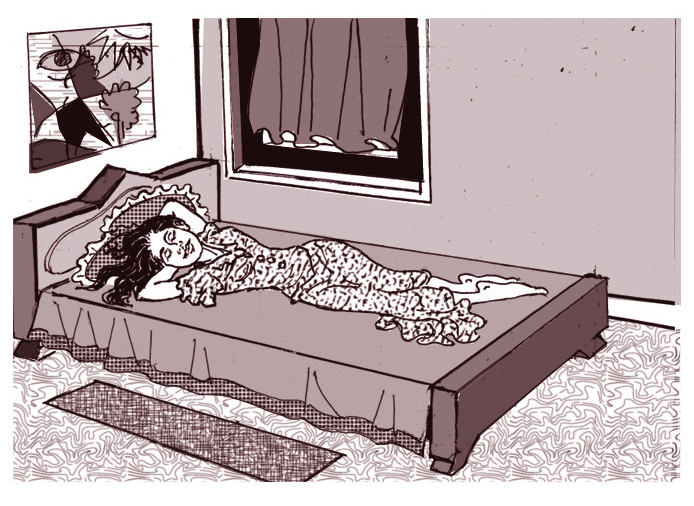

Although children can sleep well, most adults have trouble getting a good night’s sleep. They go to bed each night, but find it difficult to sleep. While in bed they toss and turn until daybreak. Such people cannot be expected to do any work properly. Upon waking they get ready to go for work, but they feel exhausted. While travelling to workplaces they doze off on buses and trains. In fact sleep deprivation leads to depression. Then they seek medical help to get over the problem.

Some people take sleeping pills without consulting a doctor. Sleeping pills might work for a few days, but you will find it difficult to drag yourself out of bed. What is more, you will feel drowsy right throughout the day. If you take sleeping pills regularly, you will get addicted to them.

A recent survey has revealed that millions of Asians suffer from insomnia – defined as an inability to fall asleep or to sleep through the night. When you do not get enough sleep for a long time, you might need medical treatment. According to a survey by National University Hospital in Singapore, 15 percent of people in the country suffer from insomnia. This is bad news coming from a highly developed country in Asia. It is estimated that one third of Asians have trouble sleeping. As such it has become a serious problem even for Sri Lankans.

Insomnia

Those who fail to take proper treatment for insomnia run the risk of sleep deprivation. A Japanese study reveals that those who sleep five hours or less are likely to suffer a heart attack. A healthy adult needs at least seven hours of sleep every day. When you do not get the required number of hours for sleep, your arteries may be inflamed. Sleep deprived people run the risk of contracting diabetes and weight gain. An American survey reveals that children who do not get deep sleep may be unnaturally small. This is because insomnia suppresses growth hormones.

It is not the length of sleep that matters. The phases of sleep are more important than the number of hours you sleep. Scientists have found that we go through several cycles of 90 minutes per night. Every cycle consists of three phases: light sleep, slumber sleep and dream sleep. When you are in deep sleep your body recuperates. When you dream your mind relaxes. Light sleep is a kind of transition between the two.

Although adults should get a minimum seven hours of sleep, the numbers may vary from person to person. In other words, some people need more than seven hours of sleep while others may need less. After the first phase of light sleep you enter the deep sleep phase which may last a few minutes. The time you spend in deep sleep may decrease according to the proportion of light sleep and dream sleep.

Napoleon Bonaparte

It is strange but true that some people manage with little sleep. They skip the light sleep and recuperate in deep sleep and dream sleep. For instance, Napoleon Bonaparte used to sleep only for four hours a night. On the other hand, we sleep at different times of the day. Some people – known as ‘Larks’ – go to bed as early as 8 p.m. There are ‘night owls’ who go to bed after midnight. Those who go to bed late and get up early are a common sight. Some of them nod off in the afternoon. This shows that we have different sleep rhythms. Dr Edgardo Juan L. Tolentino of the Philippine Department of Health says, “Sleep is as individual as our thumb prints and patterns can vary over time. Go to bed only when you are tired and not because it’s time to go to bed.”

If you are suffering from sleep deprivation, do not take any medication without consulting a doctor. Although sleeping pills can offer temporary relief, you might end up as an addict. Therefore take sleeping pills only on a doctor’s prescription. He will decide the dosage and the duration of the treatment. What is more, do not increase the dose yourself and also do not take them with alcohol.

You need to exercise your body in order to keep it in good form. However, avoid strenuous exercises late in the evening because they would stimulate the body and increase the blood circulation. This does not apply to sexual activity which will pave the way for sound sleep. If you are unable to enjoy sleep, have a good look at your bedroom. The bedroom and the bed should be comfortable. You will also fall asleep easily in a quiet bedroom. Avoid bright lights in the bedroom. Use curtains or blinds to darken the bedroom. Use a quality mattress with proper back support.

Methods

Before consulting a doctor, you may try out some of the methods given below:

* Always try to eat nutritious food. Some doctors advise patients to take a glass of red wine before going to bed. However, too much alcohol will ruin your sleep. Avoid smoking before going to bed because nicotine impairs the quality of sleep.

* Give up the habit of drinking a cup of coffee before bedtime because caffeine will keep you awake. You should also avoid eating a heavy meal before going to bed. A big meal will activate the digestive system and it will not allow the body to wind down.

* Always go to bed with a relaxed mind. This is because stress hormones in the body can hinder sleep. Those who lead stressful lives often have trouble sleeping. Such people should create an oasis between the waking day’s events and going to bed. The best remedy is to go to bed with a novel. Half way through the story you will fall asleep.

* Make it a point to go to bed at a particular time every day. When you do so, your body will get attuned to it. Similarly, try to get up at the same time every day, including holidays. If you do so, such practices will ensure your biological rhythm.

* Avoid taking a long nap in the afternoon. However, a power nap lasting 20 to 30 minutes will revitalise your body for the rest of the day.

* If everything fails, seek medical help to get over your problem.

(karunaratners@gmail.com)

By R.S. Karunatne

Features

Environmental awareness and environmental literacy

Two absolutes in harmonising with nature as awareness sparks interest – Literacy drives change

Hazards teach lessons to humanity.

Before commencing any movement to eliminate or mitigate the impact of any hazard there are two absolutes, we need to pay attention to. The first requirement is for the society to gain awareness of the factors that cause the particular hazard, the frequency of its occurrence, and the consequences that would follow if timely action is not taken. Out of the three major categories of hazards that have been identified as affecting the country, namely, (i) climatic hazards (floods, landslides, droughts), (ii) geophysical hazards (earthquakes, tsunamis), and (iii) endemic hazards (dengue, malaria), the most critical category that frequently affect almost all sectors is climatic hazards. The first two categories are natural hazards that occur independently of human intervention. In most instances their occurrence and behaviour are indeterminable. Endemic hazards are a combination of both climatic hazards and human negligence.

ENVIRONMENTAL AWARENESS

‘In Ceylon it never rains but pours’ – Cyclone Ditwah and Our Experiences

Climatic hazards, as experienced in Sri Lanka are dependent on nature, timing and volume of rainfall received during a year. The patterns of rainfall received indicate that, in most instances, rainfalls follow a rhythmic pattern, and therefore, their advent and ferocity as well as duration could in most instances be forecast with near accuracy. Based on analyses of long-term mean monthly rainfall data, Dr. George Thambyahpillay (Citation, University of Ceylon Review vol. XVI No. 3 & 4 Jul.-Oct 1958, pp 93-106 1958) produced a research paper wherein he exposed a certain Rainfall Rhythm in Ceylon. He opens his paper with the statement ‘In Ceylon it never rains but it pours’, which clearly shows both the velocity and the quantum of rain that falls in the island. ‘It is an idiom which expresses that ‘when one bad thing happens, a lot of other bad things also happen, making the situation even worse’. How true it is, when we reminisce short and long term impacts of the recent Ditwah cyclone.

Proving the truism of the above phrase we have experienced that many climatic hazards have been associated with the two major seasonal rainy phases, namely, the Southwest and Northeast monsoons, that befall in the two rainy seasons, May to September and December to February respectively. This pattern coincides with the classification of rainy seasons as per the Sri Lanka Met Department; 1) First inter-monsoon season – March-April, 2) Southwest monsoon – May- September, 3) Second Inter-monsoon season – October-November, and 4) Northeast monsoon – December-February.

The table appearing below will clearly show the frequency with which climatic hazards have affected the country. (See Table 1: Notable cyclones that have impacted Sri Lanka from 1964-2025 (60 years)

A marked change in the rainfall rhythm experienced in the last 30 years

An analysis of the table of cyclones since 1978 exposes the following important trends:

(i) The frequency of occurrence of cyclones has increased since 1998,

(ii) Many cyclones have affected the northern and eastern parts of the country.

(iii) Ditwah cyclone diverged from this pattern as its trajectory traversed inland, affecting the entire island. (similar to cyclones Roanu and Nada of 2016).

(iv) A larger number of cyclones occur during the second inter-monsoon season during which Inter-Monsoonal Revolving Storms frequently occur, mainly in the northeastern seas, bordering the Bay of Bengal. Data suggests the Bay of Bengal has a higher number of deadlier cyclones than the Arabian Sea.

(v) Even Ditwah had been a severe cyclonic outcome that had its origin in the Bay of Bengal.

(vi) There were several cyclones in the years 2016 (Roanu and Nada), 2020 (Nivar and Burevi), 2022 (Asani and Mandous) and 2025 (Montha and Ditwah). In 2025, exactly a month before Ditwah, (November 27, 2025) cyclone Montha affected the country’s eastern and northern parts (October 27) – a double whammy.

(vii) Climatologists interpret that Sri Lanka being an island in the Indian Ocean, the country is vulnerable to cyclones due to its position near the confluence of the Arabian Sea, the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean.

(viii) The island registers increased cyclonic activity, especially in the period between October and December.

The need to re-determine the paddy cultivation seasons Yala and Maha vis-a-vis changing rainfall patterns

Sri Lanka had been faithfully following the rainfall patterns year in year out, in determining the Maha and Yala paddy cultivation seasons. The Maha season falls during the North-east monsoon from September to March in the following year. The Yala season is effective during the period from May to August. However, the current changes in the country’s rainfall pattern, would demand seriously reconsidering these seasons numerous cyclones had landed in the past few years, causing much damage to paddy as well as other cultivations. Cyclones Montha and Ditwah followed one after the other.

The need to be aware of the land we live in Our minds constantly give us a punch-list of things to fixate on. But we wouldn’t have ever thought about whether the environments we live in or do our businesses are hazardous, and therefore, that item should be etched in our punch-list. Ditwah has brought us immense sorrow and hardships. This unexpected onslaught has, therefore, driven home the truth that we need to be ever vigilant on the nature of the physical location we live in and carry on our activities. Japanese need not be told as to how they should act or react in an earthquake or a tsunami. Apart from cellphone-indications almost simultaneously their minds would revolve around magnitude of the earthquake and seismic intensity, tsunami, fires, electricity and power, public transportation, and what to do if you are inside a building or if you are outdoors.

Against this backdrop it is really shocking to know of the experiences of both regional administrators and officials of the NBRO (National Building Research Organisation) in their attempts to persuade people to shift to safer locations, when deluges of cyclone Ditwah were expected to cause floods and earth slips/ landslides

Our most common and frequently occurring natural hazards

Apart from the Tsunami (December 26, 2004), that caused havoc in the Northeastern and Southern coastal belts in the country, our two most natural hazards that take a heavy toll on people’s lives and wellbeing, and cause immense damage to buildings, plantations, and critical infrastructure have been periodic floods and landslides. It has been reported that Ditwah has caused ‘an estimated $ 4.1 billion in direct physical damage to buildings, agriculture and critical infrastructure, which include roads, bridges, railway lines and communication links. It is further reported that total damage is equivalent to 4% of the country’s GDP.’

Floods and rain-induced landslides demand high alert and awareness

As the island is not placed within the ‘Ring of Fire’ where high seismic activity including earthquakes and volcanic activity is frequent, Sri Lanka’s notable hazards that occur almost perennially are floods and landslides; these calamities being consequent upon heavy rains falling during both the monsoonal periods, as well as the intermonsoonal periods where tropical revolving storms occur. When taking note of the new-normal rhythm of the country’s rainfall, those living in the already identified flood-basins would need to be ever vigilant, and conscious of emergency evacuation arrangements. Considering the numbers affected and distress caused by floods and disruptions to commercial activities, in the Western province, some have opined that priority would have been given to flood-prevention schemes in the Kelani river basin, over the Mahaweli multi-development programme.

Geomorphic processes carry on regardless, in reshaping the country’s geomorphological landscape

Geomorphic processes are natural mechanisms that eternally shape the earth’s surface. Although endogenic processes originating in the earth’s interior are beyond human control, exogenic processes occur continuously on or near the earth’s surface. These processes are driven by external forces, which mainly include:

(i) Weathering: rock-disintegration through physical, chemical and biological processes, resulting in soil and sediment formation.

(ii) Erosion: Dislocation/ removal and movement of weathered materials by water and wind (as ice doesn’t play a significant role in the Tropics).

(iii) Transportation: The shifting of weathered material to different locations often by rivers, wind, heavy rains,

(iv) Deposition: Transported material being settled forming new landforms, lowering of hills, and flattening of undulated land or depositing in the seabed.

What we witnessed during heavy rains caused by cyclone Ditwah is the above process, what geomorphologists refer to as ‘denudation’. This process is liable to accelerate during spells of heavy rain, causing landslides, landfalls, earth and rock slips/ rockslides and landslides along fault lines.

Hence, denudation is quite a natural phenomenon, the only deviation being that it gets quickened during heavy rains when gravitational and other stresses within a slope exceed the shear strength of the material that forms slopes.

It is, therefore, a must that both people and relevant authorities should be conscious of the consequences, as Ditwah was not the first cyclone that hit the country. Cyclone Roanu in May 2016 caused havoc by way of landslides, Aranayake being an area severely affected.

Conscious data-studies and analyses and preparedness; Two initials to minimise potential dangers

Sri Lanka has been repeatedly experiencing heavy rain–related disasters as the table of cyclones clearly shows (numbering 22 cyclones within the last 60 years). Further, Sri Lanka possesses comprehensive hazard profiles developed to identify and mitigate risks associated with these natural hazards.

A report of the Department of Civil Engineering, University of Moratuwa, says “Rain induced landslides occur in 13 major districts in the central highland and south western parts of the country which occupies about 20-30% of the total land area, and affects 30-38% of total population (6-7.6 Million). The increase of the number of landslides and the affected areas over the years could be attributed to adverse changes in the land use pattern, non-engineered constructions, neglect of maintenance and changes in the climate pattern causing high intensity rainfalls.”

ENVIRONMENTAL LITERACY

Environmental awareness being simply knowing facts will be of no use unless such knowledge is coupled with environmental literacy. Promoting environmental literacy is crucial for meeting environmental challenges and fostering sustainable development. In this context literacy involves understanding ecological principles and environmental issues, as well as the skills and techniques needed to make informed decisions for a sustainable future. This aspect is the most essential component in any result-oriented system to mitigate periodic climate-related hazards.

Environmental literacy rests upon several crucial pillars

The more important pillars among others being:

· Data-based comprehensive knowledge of problems and potential solutions

· Skills to analyse relevant data and information critically, and communicate effectively the revelations to relevant agencies promptly and accurately.

· Identification and Proper interconnectedness among relevant agencies

· Disposition – The attitudes, values and motivation that drive responsible environmental behaviour and engagement.

· Action – The required legal framework and the capacity to effectively translate knowledge, skills and disposition into solid action that benefits the environment.

· Constant sharing of knowledge with relevant international bodies on the latest methods adopted to harmonise human and physical environments.

· Education programmes – integrating environmental education into formal curricula and equipping students with a comprehensive understanding of ecosystems and resource management. Re-structuring the geography syllabus, giving adequate emphasis to environmental issues and changing patterns of weather and overall climate, would seem a priority act.

· Experiential learning – Organising and engaging in field studies and community projects to gain practical insights into environmental conservation.

· Establishing area-wise warning systems, similar to Tsunami warning systems.

· Interdisciplinary Approaches to encourage students to relate ecological knowledge with such disciplines as geology, geography, economics and sociology.

· Establishing Global Collaboration – Leveraging technology and digital platforms to expand access to environmental education and enhance awareness on global environmental issues.

· Educating the farming community especially on the changes occurring in weather and climate.

· Circumventing high and short duration rainfall extremes by modifying cultivation patterns, and introducing high yielding short-duration yielding varieties, including paddy.

· Soil management that reduces soil erosion

· Eradicating misconceptions that environmental literacy is only for scientists (geologists), environmental professionals and relevant state agencies.

A few noteworthy facts about the ongoing climatic changes

1. The year 2025 was marked by one of the hottest years on record, with global

temperatures surpassing 1.5ºC.

2. Russia has been warming at more than twice the global average since 1976, with 2024 marking the hottest year ever recorded.

3. Snowfalls in the Sahara – a rare phenomenon, with notable occurrences recorded in recent years.

4. Monsoon rains in the Indian Subcontinent causing significant flooding and landslides

5. Warming of the Bay of Bengal, intensifying weather activity.

6. The Himalayan region, which includes India, Nepal, Pakistan, and parts of China, experiencing temperatures climbing up to 2ºC above normal, along with widespread above-average rainfall.

7. Sri Lanka experienced rainfall exceeding 300 m.m. in a single day, an unprecedented occurrence in the island’s history. Gammaduwa, in Matale, received 540 m.m. of rainfall on a day, when Ditwah rainfall was at its peak.

The writer could be contacted at kalyanaratnekai@gmail.com

by K. A. I. KALYANARATNE ✍️

Former Management Consultant /

Senior Manager, Publications

Postgraduate Institute of Management,

University of Sri Jayewardenepura,

Vice President, Hela Hawula

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoHealth Minister sends letter of demand for one billion rupees in damages

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoIt’s all over for Maxi Rozairo

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoLeading the Nation’s Connectivity Recovery Amid Unprecedented Challenges

-

News12 hours ago

News12 hours agoPrivate airline crew member nabbed with contraband gold

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoRemembering Douglas Devananda on New Year’s Day 2026

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoDr. Bellana: “I was removed as NHSL Deputy Director for exposing Rs. 900 mn fraud”

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoDons on warpath over alleged undue interference in university governance

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoRebuilding Sri Lanka Through Inclusive Governance