Features

More on keeping the nation fed during July 1983 riots

The question of extending credit to traders to maintain stocks of rice, flour and sugar came up next. They did have serious problems due to the shortened banking hours. This had to be financed. We had already extended credit to companies and firms through the Chambers of Commerce and Industry, and this was working well. The overall climate in the country was still murky and far from settled. The ready availability of food was a critical factor in relieving people of a sense of anxiety and stress, and in restoring normalcy. But here we ran the risk of some of the stocks advanced on credit not being paid for.

I informed the Minister, as well as the Cabinet Secretary Mr. G.V.P. Samarasinghe who was also a close adviser of the President, that I was going to take the risk of authorizing advances on a studied basis. The free availability of the staple commodities was vital. It would also relieve the pressure on the Co-operatives which was nearly at breaking point. The Minister approved. The Cabinet Secretary told me. “We have already lost billions, another 100 million won’t matter.”

I for my part was determined not to lose anything. We organized a rapid screening system which identified those to whom credit would be extended. Two weeks credit was extended to them. Concurrently I formed a sub unit headed by an Assistant Accountant, whose responsibility was to chase after the debtors and ensure that they paid. There was no interest charged. Among the many items reviewed at my daily meetings this item was one. The system worked. We recovered everything that was due to us except for Rs. 25,000 from a party to whom we were compelled to give credit due to intense political pressure. This pressure did not come from the Minister. He always acted properly.

President Jayewardene’s order

We had got to a point, where with great difficulty and almost round the clock work by numerous officials, the situation was substantially under control, when one morning the President rang me. “Pieris,” he said, “My security people tell me that they cannot enforce the curfew properly because large numbers of your lorries are running all over the place. Please get this stopped.” I tried to explain to him the consequences of doing so. If the thousands of wholesale and retail points could not be stocked on a continuous basis, there would not be food available. Then he would be faced with an undreamed of security situation.

The President was as usual calm and affable, but stubborn. It was obvious that some security advisors who were totally ignorant of the implications of such a decision had literally brain-washed the President. “Pieris,” the President continued after listening to me. “No, get the lorries off the road during curfew hours, otherwise my people would have to shoot them!” The latter part was said more humorously than seriously. But it was clear that he was not prepared to give his mind to the serious implications involved. I had no choice, but to say that I will pass the message down.

This was both frightening and demoralizing. I tried to get at the Minister. He was not available. It was clear that the Minister had to be briefed about the consequences of this decision and persuaded to go and meet the President. But pending this, some action had to be taken at least to create the appearance that steps were being taken to implement the decision. I sent for Austin Fernando, the Commissioner of Cooperative Development. He was not working from his office at Duke Street, but from the Head Office of the Colombo North Multi-Purpose Co-operative Society in the Pettah.

When he came, I briefed him on what had happened. He was as surprised and frustrated as I was. Only we who worked 14 hours a day. covering every detail and solving every problem that came up could see the magnitude of the blunder that was ordered to be committed. We were convinced that if the smooth flow of the operation which included the port, food store complexes, the co-operatives and the private sector dealers, was interfered with that an adverse impact would result within 24 hours. If it went on for 48 hours, there would have been a complete breakdown in food supplies leading to riots and serious civil unrest.

Austin and I therefore decided to play for time. We issued some desultory verbal instructions here and there, just to be able to say that we were on the job, if someone checked back. In the meantime, a search was going on for the Minister. When we finally contacted him it was early afternoon. He saw the problem at once and was appalled at the decision. He undertook to meet the President in his home at Ward Place during early evening. Eventually, the decision was rescinded and sanity prevailed.

A few days after these problems arose, Bradman Weerakoon was appointed as the Commissioner General of Essential Services. His job was to deal with any bottlenecks and exercise an overall co-ordination. As far as food was concerned he had no problem. We only provided him with the daily statistics pertaining to our efforts. All of us functioned under draconian Emergency Regulations. I was sent a set under confidential cover. I was quite surprised to find that in the maintenance of essential services – and food was one of the most essential – the regulations gave me powers to requisition buildings, vehicles and even persons!

I did not show them to anyone else, securely locked them up in my drawer and never looked at them again. It has always been my view that practically anything you want can be achieved without using power, just by a process of rational discussion and understanding. During those difficult days too, events fortified this belief of mine. I did not requisition anything.

Standards in the public service

Before I leave this subject there are a few miscellaneous matters of interest which I wish to record. Mr. Pulendiran the Food Commissioner and his wife had suffered serious loss of property and psychological trauma when their house and car were burnt down by mobs. Their house was fairly close to the Dehiwela canal bank, and the mob had originated from the shanty dwellers living there. Fortunately his house had been insured. But now they had no place to stay. They were temporarily accommodated in quarters at the Prima Bakery in Rajagiriya.

Two days after these events, he turned up for work. Even their clothes were burnt with the house. I told him to settle down and rest for a few days. But he wouldn’t hear of it. He was a public servant and the head of an important department, and he wished to discharge his responsibilities. All of us were happy to have him back. Many helped them with clothes and other requisites. The dedication of Mr. Pulendiran reflected the public service at its best.

I saw at close quarters how scores of my own officers worked during this period. There was no question of pushing or prodding. They worked punishingly long hours, very often without adequate or proper food. Many of them did not have time to eat, as was the case with me, on many a day. Sympathetic office aides kept us supplied with many cups of tea. Here again they decided when to serve the tea. There was no time for us to think about such matters. They kept a brotherly eye on us, and every time they thought we were flagging, in came the hot cups of tea which were a great restorer.

It had been my good fortune to witness this sense of public duty in many public servants. Another such was the case of my own cousin, Mr. M.B. Senanayake, who was the Senior Deputy Food Commissioner in the 1960’s. He was at the time living in a house very close to the sea at Kollupitiya. One violently stormy night a huge wave engulfed the house and they barely escaped with their lives. The garage outside was demolished by the wave and his car was in the sea with a photograph of it in the newspapers. The furniture, clothes and much else were soaked by the sea water.

Yet, with all this disruption, chaos and personal loss, he was in office at 10 a.m. to meet an Australian delegation, whilst his personal effects were being put out to dry on both sides of the public road. I remember reading Neville Jayaweera’s writing about his experience as Government Agent, Vavuniya during the time of the JVP insurgency of 1971. Many public servants had faced enormous dangers and personal loss, but kept on working and doing their duty. Some died at their posts. Criticism of the public service must be balanced by the great and lasting contributions made by it. Unfortunately, no one had done any sustained work in this area.

A conversation with a lady public servant

At the beginning of the week following, the terrible events of “Black Friday,” a senior Tamil lady public servant telephoned me and said she wished to see me to obtain some advice. I gave her an immediate appointment. When she met me she said that some of her close relations who were in London, wanted her to leave and come over immediately. She was not married. She was defiant. She felt that if she left it would be like running away. She was no coward and she did not wish to appear to be one.

“Damn it Sir,” she said. “This is my country. Why should I run away from my country?” I admired her spirit and her courage. But she was being pestered so much by her relations, she needed advice as to what to do. At that moment she was not capable of clear thought. I said that she was casting a heavy responsibility on me. Having thought about the matter, I told her that all of us had been shaken by the events of the previous Friday in particular. I had no idea whatsoever, as to what really was happening, who was behind it and what further course it would take.

Under these circumstances, my view was that personal safety came first. Therefore, I advised her to go abroad for a short period, and come back once things settled down. She thanked me and said that she would follow my advice. Thereafter she took leave of me, got up and walked towards the door. Suddenly, she turned back and walking up to me said “Sir, why can’t we send all our bloody politicians on compulsory leave for 10 years?” She was exceedingly generous. This was a time when a considerable section of intelligent and educated people belonging to all communities wished to visit far harsher punishments on our politicians of all colours, hues, groups and persuasions.

Complexities of human behaviour

The country gradually settled down and a sense of normalcy was restored. Amidst the gloom, there were shinning beacons of light. Many Sinhalese took great risks in sheltering Tamil families in their own homes. Most of the neighbourhoods did their best to protect both life and property. Down our own lane the Sinhalese, in alliance with others in adjoining lanes saw to it that not a single stone was thrown at a house. So, when our Tamil neighbours returned from their stay in a refugee camp, they had only sweeping and dusting to do.

The Sinhalese driver of the Chief Accountant Food Department Mr. Khatamuttu, risked his life in getting him and his family out of their house in Ratmalana under extremely trying and even dangerous circumstances. Such acts were numerous and widespread. Most of the acts of violence were orchestrated by squads of goons from outside. The neighbourhoods held. and the sense of community never disappeared. Human nature however is very strange. There are some people who cannot triumph over their prejudices whatever the circumstances.

A senior public servant who was helping out at the refugee camp established at Mahanama College told me that one day there was a near riot when the lunch packets were being distributed, because some who had claimed to be “high caste” Tamils vehemently objected to some deemed to be “low caste” being served first. They had also objected to some of those “low caste” being accommodated upstairs in one of the school buildings whilst some of those of “high caste” were being accommodated downstairs. He was a Sinhalese. There was a caste system operating amongst the Sinhalese, which had become much watered down over the years. This was his first exposure to the rigidities of the caste system as practiced by some Tamils.

(Excerpted from In Pursuit of Governance, autobiography of MDD Pieris) ✍️

Features

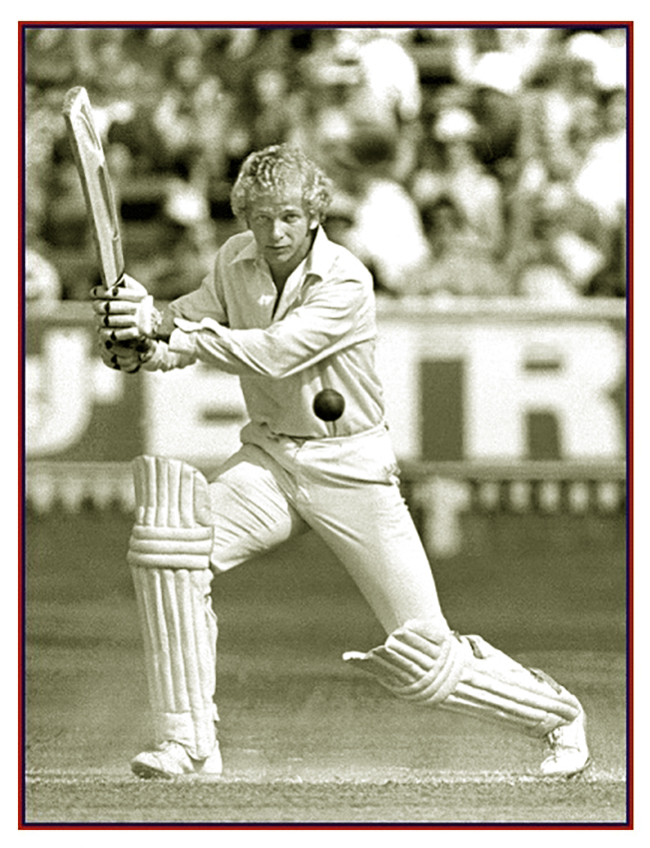

When Batting Was Poetry: Remembering David Gower

For many Sri Lankans growing up in the late nineteen fifties and early sixties, our cricketing heroes were Englishmen. I am not entirely sure why that was. Perhaps it was a colonial hangover, or perhaps it reflected the way cricket was taught locally, with an emphasis on technical correctness, a high left elbow, and the bat close to the pad. English cricket, with its traditions and orthodoxy, became the benchmark.

I, on the other hand, could not see beyond Sir Garfield Sobers and the West Indian team. Sir Garfield remains my all-time hero, although only by a whisker ahead of Muttiah Muralitharan. For me, Caribbean flair and attacking cricket were infinitely superior to the Englishmen’s conservatism and defensive approach.

That said, England has produced many outstanding cricketers, with David Gower and Ian Botham being my favourites. Players such as Colin Cowdrey, Tom Graveney, Mike Denness, Tony Lewis, Mike Brealey, Alan Knott, Derek Underwood, Tony Greig, and David Gower were great ambassadors for England, particularly when touring the South Asian subcontinent, which posed certain challenges for touring sides until about three decades ago. Their calm and dignified conduct when touring is a contrast to the behaviour of the current lot.

I am no longer an avid cricket viewer, largely because my blood pressure tends to rise when I watch our Sri Lankan players. Therefore, I was pleasantly surprised recently when I was flipping through the TV channels to hear David Gower’s familiar voice commentating. It brought back fond memories of watching him bat during my time in the UK. I used to look forward to the summer for two reasons. To feel the sun on my back and watch David Gower bat!

A debut that announced a star

One of my most vivid cricketing memories is watching, in 1978, a young English batsman pull the very first ball he faced in Test cricket to the boundary. Most debutants play cautiously, trying to avoid the dreaded zero, but Gower nonchalantly swivelled and pulled a short ball from Pakistan’s Liaquat Ali for four. It was immediately apparent that a special talent had arrived.

To place that moment in perspective, Marvan Atapattu—an excellent Sri Lankan batsman—took three Tests and four innings to score his first run, yet later compiled 16 Test centuries.

Gower went on to score 56 in his first innings and captivated spectators with his full repertoire of strokes, particularly his exquisite cover drive. It is often said that a left-hander’s cover drive is one of the most pleasurable sights in cricket, and watching Sobers, Gower, or Brian Lara execute the cover drive made the entrance ticket worthwhile.

A young talent in a time of change

Gower made his Test debut at just 21, rare for an English player of that era. World cricket was in turmoil due to the Kerry Packer revolution, and England had lost senior players such as Tony Greig, Alan Knott, and Derek Underwood. Selectors were searching for young talent, and Gower’s inclusion injected fresh impetus.

Gower scored his first Test century in only his fourth match, just a month after his debut, against New Zealand, and a few months later scored his maiden Ashes century at Perth.

He finished with 18 Test centuries from 117 matches. His finest test innings, in my view, was the magnificent 154 not out at Kingston in 1981 against Holding, Marshall, Croft, and Garner. Batting for nearly eight hours and facing 403 balls, he set aside flair for determination to save the Test.

He and Ian Botham also benefited from playing their initial years under Mike Brealey, an average batsman but an outstanding leader. Rodney Hogg, the Australian fast bowler, famously said Brealey had a ‘degree in people’, and both young stars flourished under his guidance.

Captaincy and criticism and overall record

Few English batsmen delighted and frustrated spectators and analysts as much as Gower. The languid cover drive, so elegant and so pleasurable to the spectators, also resulted in a fair number of dismissals that, at times, gave the impression of carelessness to both spectators and journalists.

Despite his approach, which at times appeared casual, he was appointed as captain of the English team in 1983 and served for three years before being removed in 1986. He was again appointed captain in 1989 for the Ashes series. He led England in 1985 to a famous Ashes series win as well as a series win in India in1984-85.

In the eyes of some, the captaincy might not have been the best suited to his style of play. However, he scored 732 runs whilst captaining the team during the 1985 Ashes series, proving that he was able handle the pressure.

Under Gower, England lost two consecutive series to the great West Indian teams 5-0, which led to the coining of the phrase “Blackwashed”! He was somewhat unlucky that he captained the English team when the West Indies were at the peak, possessing a fearsome array of fast bowlers.

David Gower scored 3,269 test runs against Australia in 42 test matches. He scored nine centuries and 12 fifties, averaging nearly 45 runs per inning. His record against Australia as an English batsman is only second to Sir Jack Hobbs. Scoring runs against Australia has been a yardstick in determining how good a batsman is. Therefore, his record against Australia can easily rebut the critics who said that he was too casual. He scored 8,231 runs in 117 test matches and 3,170 runs in 114 One Day Internationals.

A gentleman of the game free of controversies

Unlike the other great English cricketer at the time, Ian Botham, David was not involved in any controversies during his illustrious career. The only incident that generated negative press was a low-level flight he undertook in a vintage Tiger Moth biplane in Queensland during the 1990-91 Ashes tour of Australia. The team management and the English press, as usual, made a mountain out of a molehill. David retired from international cricket in 1992.

In 1984, during the tour of India, due to the uncertain security situation after the assassination of the then Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, the English team travelled to Sri Lanka for a couple of matches. I was fortunate enough to get David to sign his book “With Time to Spare”. This was soon after he returned to the pavilion after being dismissed. There was no refusal or rudeness when I requested his signature.

He was polite and obliged despite still being in pads. Although I did not know David Gower, his willingness that day to oblige a spectator exemplified the man’s true character. A gentleman who played the game as it should be, and a great ambassador of England and world cricket. He was inducted into the ICC Cricket Hall of Fame in 2009 and appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in 1992 for his services to sport.

By Sanjeewa Jayaweera

Features

Sri Lanka Through Loving Eyes:A Call to Fix What Truly Matters

Love of country, pride, and the responsibility to be honest

I am a Sri Lankan who has lived in Australia for the past 38 years. Australia has been very good to my family and me, yet Sri Lanka has never stopped being home. That connection endures, which is why we return every second year—sometimes even annually—not out of nostalgia, but out of love and pride in our country.

My recent visit reaffirmed much of what makes Sri Lanka exceptional: its people, culture, landscapes, and hospitality remain truly world-class. Yet loving one’s country also demands honesty, particularly when shortcomings risk undermining our future as a serious global tourism destination.

When Sacred and Iconic Sites Fall Short

One of the most confronting experiences occurred during our visit to Sri Pada (Adam’s Peak). This sacred site, revered across multiple faiths, attracts pilgrims and tourists from around the world. Sadly, the severe lack of basic amenities—especially clean, accessible toilets—was deeply disappointing. At moments of real need, facilities were either unavailable or unhygienic.

This is not a luxury issue. It is a matter of dignity.

For a site of such immense religious and cultural significance, the absence of adequate sanitation is unacceptable. If Sri Lanka is to meet its ambitious tourism targets, essential infrastructure, such as public toilets, must be prioritized immediately at Sri Pada and at all major tourist and pilgrimage sites.

Infrastructure strain is also evident in Ella, particularly around the iconic Nine Arches Bridge. While the attraction itself is breathtaking, access to the site is poorly suited to the sheer volume of visitors. We were required to walk up a steep, uneven slope to reach the railway lines—manageable for some, but certainly not ideal or safe for elderly visitors, families, or those with mobility challenges. With tourist numbers continuing to surge, access paths, safety measures, and crowd management urgently needs to be upgraded.

Missed opportunities and first impressions

Our visit to Yala National Park, particularly Block 5, was another missed opportunity. While the natural environment remains extraordinary, the overall experience did not meet expectations. Notably, our guide—experienced and deeply knowledgeable—offered several practical suggestions for improving visitor experience and conservation outcomes. Unfortunately, he also noted that such feedback often “falls on deaf ears.” Ignoring insights from those on the ground is a loss Sri Lanka can ill afford.

First impressions also matter, and this is where Bandaranaike International Airport still falls short. While recent renovations have improved the physical space, customs and immigration processes lack coherence during peak hours. Poorly formed queues, inconsistent enforcement, and inefficient passenger flow create unnecessary delays and frustration—often the very first experience visitors have of Sri Lanka.

Excellence exists—and the fundamentals must follow

That said, there is much to celebrate.

Our stays at several hotels, especially The Kingsbury, were outstanding. The service, hospitality, and quality of food were exceptional—on par with the best anywhere in the world. These experiences demonstrate that Sri Lanka already possesses the talent and capability to deliver excellence when systems and leadership align.

This contrast is precisely why the existing gaps are so frustrating: they are solvable.

Sri Lankans living overseas will always defend our country against unfair criticism and negative global narratives. But defending Sri Lanka does not mean remaining silent when basic standards are not met. True patriotism lies in constructive honesty.

If Sri Lanka is serious about welcoming the world, it must urgently address fundamentals: sanitation at sacred sites, safe access to major attractions, well-managed national parks, and efficient airport processes. These are not optional extras—they are the foundation of sustainable tourism.

This is not written in criticism, but in love. Sri Lanka deserves better, and so do the millions of visitors who come each year, eager to experience the beauty, spirituality, and warmth that our country offers so effortlessly.

The writer can be reached at Jerome.adparagraphams@gmail.com

By Jerome Adams

Features

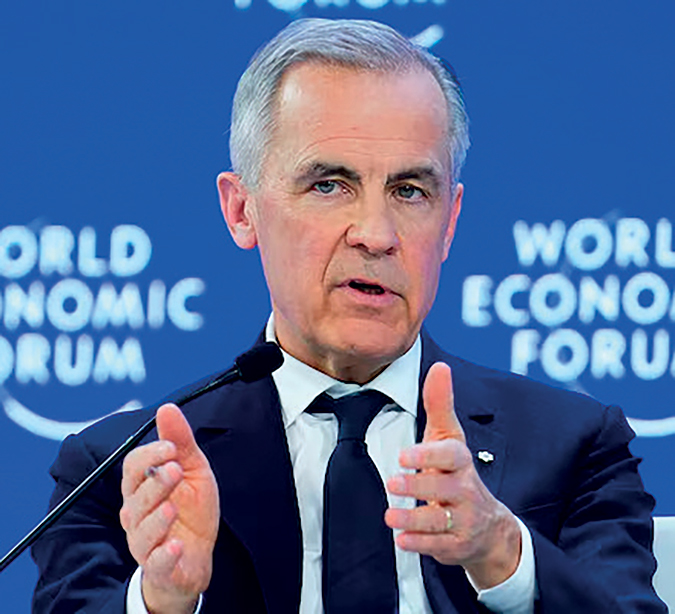

Seething Global Discontents and Sri Lanka’s Tea Cup Storms

Global temperatures in January have been polar opposite – plus 50 Celsius down under in Australia, and minus 45 Celsius up here in North America (I live in Canada). Between extremes of many kinds, not just thermal, the world order stands ruptured. That was the succinct message in what was perhaps the most widely circulated and listened to speeches of this century, delivered by Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney at Davos, in January. But all is not lost. Who seems to be getting lost in the mayhem of his own making is Donald Trump himself, the President of the United States and the world’s disruptor in chief.

After a year of issuing executive orders of all kinds, President Trump is being forced to retreat in Minneapolis, Minnesota, by the public reaction to the knee-jerk shooting and killing of two protesters in three weeks by federal immigration control and border patrol agents. The latter have been sent by the Administration to implement Trump’s orders for the arbitrary apprehension of anyone looking like an immigrant to be followed by equally arbitrary deportation.

The Proper Way

Many Americans are not opposed to deporting illegal and criminal immigrants, but all Americans like their government to do things the proper way. It is not the proper way in the US to send federal border and immigration agents to swarm urban neighbourhood streets and arrest neighbours among neighbours, children among other school children, and the employed among other employees – merely because they look different, they speak with an accent, or they are not carrying their papers on their person.

Americans generally swear by the Second Amendment and its questionably interpretive right allowing them to carry guns. But they have no tolerance when they see government forces turn their guns on fellow citizens. Trump and his administration cronies went too far and now the chickens are coming home to roost. Barely a month has passed in 2026, but Trump’s second term has already run into multiple storms.

There’s more to come between now and midterm elections in November. In the highly entrenched American system of checks and balances it is virtually impossible to throw a government out of office – lock, stock and barrel. Trump will complete his term, but more likely as a lame duck than an ordering executive. At the same time, the wounds that he has created will linger long even after he is gone.

Equally on the external front, it may not be possible to immediately reverse the disruptions caused by Trump after his term is over, but other countries and leaders are beginning to get tired of him and are looking for alternatives bypassing Trump, and by the same token bypassing the US. His attempt to do a Venezuela over Greenland has been spectacularly pushed back by a belatedly awakening Europe and America’s other western allies such as Australia, Canada and New Zealand. The wags have been quick to remind us that he is mostly a TACO (Trump always chickens out) Trump.

Grandiose Scheme or Failure

His grandiose scheme to establish a global Board of Peace with himself as lifetime Chair is all but becoming a starter. No country or leader of significant consequence has accepted the invitation. The motley collection of acceptors includes five East European countries, three Central Asian countries, eight Middle Eastern countries, two from South America, and four from Asia – Cambodia, Vietnam, Indonesia and Pakistan. The latter’s rush to join the club will foreclose any chance of India joining the Board. Countries are allowed a term of three years, but if you cough up $1 billion, could be member for life. Trump has declared himself to be lifetime chair of the Board, but he is not likely to contribute a dime. He might claim expenses, though. The Board of Peace was meant to be set up for the restoration of Gaza, but Trump has turned it into a retirement project for himself.

There is also the ridiculous absurdity of Trump continuing as chair even after his term ends and there is a different president in Washington. How will that arrangement work? If the next president turns out to be a Democrat, Trump may deny the US a seat on the board, cash or no cash. That may prove to be good for the UN and its long overdue restructuring. Although Trump’s Board has raised alarms about the threat it poses to the UN, the UN may end up being the inadvertent beneficiary of Trump’s mercurial madness.

The world is also beginning to push back on Trump’s tariffs. Rather, Trump’s tariffs are spurring other countries to forge new trade alliances and strike new trade deals. On Tuesday, India and EU struck the ‘mother of all’ trade deals between them, leaving America the poorer for it. Almost the next day , British Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer and Chinese leader Xi Jinping announced in Beijing that they had struck a string of deals on travel, trade and investments. “Not a Big Bang Free Trade Deal” yet, but that seems to be the goal. The Canadian Prime Minister has been globe-trotting to strike trade deals and create investment opportunities. He struck a good reciprocal deal with China, is looking to India, and has turned to South Korea and a consortium from Germany and Norway to submit bids for a massive submarine supply contract supplemented by investments in manufacturing and mineral industries. The informal first-right-of-refusal privilege that US had in Canada for defense contracts is now gone, thanks to Trump.

The disruptions that Trump has created in the world order may not be permanent or wholly irreversible, as Prime Minister Carney warned at Davos. But even the short term effects of Trump’s disruptions will be significant to all of US trading partners, especially smaller countries like Sri Lanka. Regardless of what they think of Trump, leaders of governments have a responsibility to protect their citizens from the negative effects of Trump’s tariffs. That will be in addition to everything else that governments have to do even if they do not have Trump’s disruptions to deal with.

Bland or Boisterous

Against the backdrop of Trump-induced global convulsions, politics in Sri Lanka is in a very stable mode. This is not to diminish the difficulties and challenges that the vast majority of Sri Lankans are facing – in meeting their daily needs, educating their children, finding employment for the youth, accessing timely health care and securing affordable care for the elderly. The challenges are especially severe for those devastated by cyclone Ditwah.

Politically, however, the government is not being tested by the opposition. And the once boisterous JVP/NPP has suddenly become ‘bland’ in government. “Bland works,” is a Canadian political quote coined by Bill Davis a nationally prominent premier of the Province of Ontario. Davis was responding to reporters looking for dramatic politics instead of boring blandness. He was Premier of Ontario for 14 years (1971-1985) and won four consecutive elections before retiring.

No one knows for how long the NPP government will be in power in Sri Lanka or how many more elections it is going to win, but there is no question that the government is singularly focused on winning the next parliamentary election, or both the presidential and parliamentary elections – depending on what happens to the system of directly electing the executive president.

The government is trying to grow comfortable in being on cruise control to see through the next parliamentary election. Its critics on the other hand, are picking on anything that happens on any day to blame or lampoon the government. The government for all its tight control of its members and messaging is not being able to put out quickly the fires that have been erupting. There are the now recurrent matters of the two AGs (non-appointment of the Auditor General and alleged attacks on the Attorney General) and the two ERs (Educational Reform and Electricity Reform), the timing of the PC elections, and the status of constitutional changes to end the system of directly electing the president.

There are also criticisms of high profile resignations due to government interference and questionable interdictions. Two recent resignations have drawn public attention and criticism, viz., the resignation of former Air Chief Marshal Harsha Abeywickrama from his position as the Chairman of Airport & Aviation Services, and the earlier resignation of Attorney-at-Law Ramani Jayasundara from her position as Chair of the National Women’s Commission. Both have been attributed to political interferences. In addition, the interdiction of the Deputy Secretary General of Parliament has also raised eyebrows and criticisms. The interdiction in parliament could not have come at a worse time for the government – just before the passing away of Nihal Seniviratne, who had served Sri Lanka’s parliament for 33 years and the last 13 of them as its distinguished Secretary General.

In a more political sense, echoes of the old JVP boisterousness periodically emanate in the statements of the JVP veteran and current Cabinet Minister K.D. Lal Kantha. Newspaper columnists love to pounce on his provocative pronouncements and make all manner of prognostications. Mr. Lal Kantha’s latest reported musing was that: “It is true our government is in power, but we still don’t have state power. We will bring about a revolution soon and seize state power as well.”

This was after he had reportedly taken exception to filmmaker Asoka Handagama’s one liner: “governing isn’t as easy as it looks when you are in the opposition,” and allegedly threatened to answer such jibes no matter who stood in the way and what they were wearing “black robes, national suits or the saffron.” Ironically, it was the ‘saffron part’ that allegedly led to the resignation of Harsha Abeywickrama from the Airport & Aviation Services. And President AKD himself has come under fire for his Thaipongal Day statement in Jaffna about Sinhala Buddhist pilgrims travelling all the way from the south to observe sil at the Tiisa Vihare in Thayiddy, Jaffna.

The Vihare has been the subject of controversy as it was allegedly built under military auspices on the property of local people who evacuated during the war. Being a master of the spoken word, the President could have pleaded with the pilgrims to show some sensitivity and empathy to the displaced Tamil people rather than blaming them (pilgrims) of ‘hatred.’ The real villains are those who sequestered property and constructed the building, and the government should direct its ire on them and not the pilgrims.

In the scheme of global things, Sri Lanka’s political skirmishes are still teacup storms. Yet it is never nice to spill your tea in public. Public embarrassments can be politically hurtful. As for Minister Lal Kantha’s distinction between governmental mandate and state power – this is a false dichotomy in a fundamentally practical sense. He may or may not be aware of it, but this distinction quite pre-occupied the ideologues of the 1970-75 United Front government. Their answer of appointing Permanent Secretaries from outside the civil service was hardly an answer, and in some instances the cure turned out to be worse than the disease.

As well, what used to be a leftist pre-occupation is now a right wing insistence especially in America with Trump’s identification of the so called ‘deep state’ as the enemy of the people. I don’t think the NPP government wants to go there. Rather, it should show creative originality in making the state, whether deep or shallow, to be of service to the people. There is a general recognition that the government has been doing just that in providing redress to the people impacted by the cyclone. A sign of that recognition is the number of people contributing to the disaster relief fund and in substantial amounts. The government should not betray this trust but build on it for the benefit of all. And better do it blandly than boisterously.

by Rajan Philips

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoComBank, UnionPay launch SplendorPlus Card for travelers to China

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoClimate risks, poverty, and recovery financing in focus at CEPA policy panel

-

Opinion3 days ago

Opinion3 days agoSri Lanka, the Stars,and statesmen

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoHayleys Mobility ushering in a new era of premium sustainable mobility

-

Opinion7 days ago

Opinion7 days agoLuck knocks at your door every day

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoAdvice Lab unveils new 13,000+ sqft office, marking major expansion in financial services BPO to Australia

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoArpico NextGen Mattress gains recognition for innovation

-

Editorial2 days ago

Editorial2 days agoGovt. provoking TUs