Features

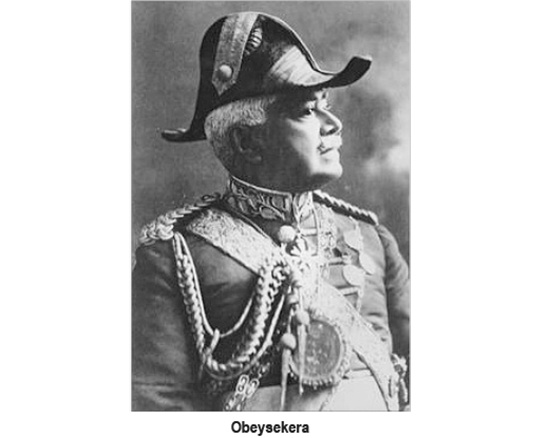

Meeting the Maha Mudaliayar as a young ASP

(Excerpted from Senior DIG Edward Gunawardena’s memoirs)

It was indeed a privilege to meet and come to know Sir James Peter Obeysekera, a doyen of the Low Country aristocracy. Although the Obeysekera family was spread far and wide in the Western Province, Batadola Walawwa situated in the Gampaha District was its seat. This was the majestic residence of Sir James. With Lady Hilda Obeysekera having passed away earlier, he lived alone at Batadola. His son, J.P. Obeysekera Jnr., who was the Member of Parliament for Attanagalla and his wife, Siva, visited him frequently and attended to all his needs.

I had heard of him. After I met JPO Jnr. at the Fountain Cafe I remembered my father (the assistant manager there) telling me that he was the son of a former Maha Mudaliyar. With Batadola in the police district of Gampaha I was anxious to meet and strike a conversation with this senior colonial official when I was posted there. I was wondering how I could make an appointment and call on him. It was my good fortune that I mentioned this to Inspector Alex Abeysekera when I visited the Nittambuwa police station one day.

Alex was quick to say that Sir James was a man I should meet. He believed that few in the younger generation would have even have heard of him, leave alone meeting him. Alex had called on him several times and Sir James had begun to look forward to his visits. Small wonder because Alex, although he had started his police career as a constable, was an erudite gentleman who spoke excellent English.

Alex lost no time in informing Sir James of his intention to visit him with the ASP of Gampaha. He telephoned me to say that Sir James would be pleased to see us in the afternoon of the Saturday to follow. Dressed in uniform I drove to the Nittambuwa police station in my car. Alex was also in uniform. He suggested that we go to Batadola in the Police Jeep.

With a laugh Alex told me that Sir James was a man who had long associated with the uniformed elite as an ADC to the Governor. In any event, in the sixties men in uniform were much respected and trusted.

Alex took the wheel and I was seated in front. The Police driver and a constable got into the rear. With the time approaching five we reached the driveway to the Batadola Walawwa. The narrow avenue of Na (ironwood) trees resembled a dark tunnel. It was cool, silent and dark. The sky could not be seen. I felt that I was in a different country. I suggested to Alex to stop for a few minutes and enjoy the ‘silence of the afternoon’!

A minute after we started off again we saw the light at the end of the tunnel of Na trees. What a fascinating sight it was! The setting sun shone on the white walled, imposing, castle-like Batadola remains a sight firmly etched in my memory. From the darkness of the avenue of Na trees Batadola certainly resembled an edifice out of this world.

Recognizing the police jeep a middle aged man, presumably a watcher, opened the main gate. Alex cautiously drove the vehicle to the portico. Before we could even get off the jeep Sir James appeared at the main entrance. Behind him stood a man dressed in a white sarong and white tunic coat buttoned to the neck. “Come in gentlemen, please make yourselves comfortable”. So saying he bade us sit down. His voice sounded squeaky.

The furniture in the sitting room consisted of settees and chairs of ebony and calamander with crimson velvet cushions. On all the chairs were heaps of books, magazines and newspapers. Alex and I had to clear the chairs of these books and magazines to sit down. Before Alex could introduce me the old man turned to Alex and good humouredly said, “So Abeysekera this young man is your boss”. With this I got up, introduced myself and shook hands with him. He was gracious enough to get up from his seat.

Dressed in a long sleeved white shirt and cotton khaki longs and wearing gold rimmed glasses he looked wiry and fit. Although in his late seventies with wooden clogs as footwear he looked quite tall. After we settled down in our seats he was curious to know my family background, my educational achievements, the school that I attended, what my brothers were doing etc. He appeared to be very pleased when I told him that I had already met his son, the MP. But he laughed and said, “that fellow is not cut out for politics. He likes to drive racing cars and pilot aeroplanes!”

I then saw the man who was dressed in white bringing a tray with two cups and saucers and a small glass tumbler which had a liquid the colour of wine. He left this tumbler on a stool near his master and brought the tray round. He then said, “I don’t know whether police people will like this drink. You know Abeysekera this is what I sip throughout the day. It is plain cold tea without sugar. It is good for your health.” I responded by saying that I too like it, but with a little lime juice and chilled.

With the time approaching 6.30 p.m. it suddenly occurred to me that Alex had mentioned about the old man’s fondness to keep on talking. His advice to me on the way was to keep mum as much as possible and to allow him to do the talking. But to get him talking I had to ask a question or two. I then told him how fascinated I was seeing the Batadola Walawwa for the first time and asked him, “Sir, how old is this lovely structure?”

His immediate response was to say that it was the oldest Walawwa in Siyane Korale. I also remember him saying that an ancestor of his, a chieftain from the south who also had Dutch blood, had been able to obtain about five hundred acres from an early British Governor to plant coconut and cinnamon. This ancestor had first built a modest house by a stream lined with bata (small bamboo). According to what he related the present structure dates back to the mid-nineteenth century. However, Sir James himself truthfully admitted that he found it difficult to recall the details of the origins of Batadola Walawwa.

At 7 p.m. sharp the man in white brought a meat mincer and mounted it on a small table near which Sir James was seated. Alex kicked my leg as if to say it is time to go. Moments later this man brought a plate with a fork and spoon. A small dish of food was also brought. I knew it was food by the colour of the green beans and carrots. I got up from my seat to indicate that the time had come to leave. “No, no, please stay, let’s talk a little more,” he said.

“How is it, Sir, that Horagolla is better known than Batadola?” “Better known? What nonsense. True, the riff-raff have heard of only Horagolla. And that too only after Banda became prime minister”; he sounded slightly agitated, but appeared to be enjoying the banter. Proud of the superiority of Batadola, Sir James began to rattle off the ancestry of the Bandaranaikes and how they had become rich.

According to him the Bandaranaikes had been ‘Poosaris’ of the Nawagamuwa Devala who had got contracts from the British Government to supply labour and metal for the construction of the Colombo — Kandy Rd.

While we were talking the man in white started putting the contents of the dish in small doses to the meat mincer and turning out little lumps of minced food to be eaten by his master. Nevertheless, he appeared to be keen to keep talking about the Bandaranaikes even whilst eating his dinner. However keen he was to go on with the conversation, I thanked him for the wonderful reception we received and got up to leave. He virtually pleaded that we should drop in often. Despite eating his dinner at the time, he walked up to the door to see us off.

A few weeks later I visited the Wathupitiwala Hospital in connection with a serious motor accident that had occurred on the Kandy — Colombo Rd at Pasyala. As I drove in, from a distance I spotted Sir James standing near the entrance. He was dressed in a lounge suit of khaki cotton drill and wearing a brown felt hat. His footwear was light brown canvas deck-shoes. He also carried a black umbrella. In every respect he resembled a typical English country gentleman.

I saluted and shook hands with him. He remembered our meeting at Batadola. Before getting into his car he thanked us again for our visit and said he’d like to meet us again. As was his practice he had visited the hospital semi-officially to inspect the buildings and premises. This hospital had been built in memory of his late wife, Lady Obeysekera.

It wasn’t long before we met Sir. James again. Alex and I had to visit a scene of murder close to the Batadola Estate and we took the opportunity to drop in at the Walawwa. Sir James greeted us warmly. “I knew that you were coming to this area. I expected you to drop in. Perhaps we can continue the discussion from where we left off.”

He appeared to be keen to tell us more about the Bandaranaikes. The jovial mood he was in was obvious. “Today you will not get plain tea”. So saying he ordered the butler to bring us iced coca cola.

Starting off the conversation he expressed the opinion that the Obeysekeras were more refined people as a clan. Most of them were Oxford or Cambridge educated. He referred to his cousins, Forester and Donald. Alex butted in having been a boxer to say that he knew Donald’s sons, Danton and Alex. He also was keen to impress on us that the Bandaranaikes particularly the late Solomon and R.F. Dias reveled in crude ribald jokes. He was in an unstoppable mood. When I interjected to say that S.W.R.D was a distinguished Oxford alumnus, “Yes the first and perhaps the last,” was his response.

Perhaps he felt that I knew more about the Bandaranaikes. He may have even thought that I was an admirer of the Bs, by the questions he began to ask me. “Have you been to Tintagel?” he asked me. I told him that I called on the Prime Minister officially at his Colombo residence. “What do you know of the ‘Maligawa’ in Cinnamon Gardens?” “I have not seen or heard of a Maligawa other than in Kandy,” was my reply.

He laughed loudly. Alex who was a silent listener provided the answer. “It is adjoining the Cinnamon Gardens police station Sir, the palatial residence of the Obeysekeras in Colombo.” Sir James was pleased. He got another starting point to educate me more about the Obeysekeras.

Continuing he told me that the Cinnamon Gardens police station is on a land donated to the Police Dept. by the Obeysekera family. Unlike Tintagel which was owned by an Englishman the Maligawa had been built at about the same time that the Batadola Walawwa had been built. He recalled the WW II years when as a young man he had been an additional ADC to the Governor.

When I showed interest he began to speak freely. According to him the Maligawa, where he lived during the war years was only second to Queen’s House. He described two luxury suites that were reserved for visiting dignitaries and other special guests. Even Queen’s House did not have such accommodation, he said.

Unlike Queen’s House the location of the Maligawa had special advantages. He had been fond of riding and the Governor’s stables had been located across the road in the race course. Geoffrey Layton and Louis Mountbatten, whenever they wanted to ride, had been his guests at the Maligawa. What has stuck in my memory is the peculiarity that Layton had, a preference to ride a piebald named Tojo, the name of the Japanese war lord! What was unsaid was that the Bandaranaikes never hosted such important people at ‘Tintagel or Horagolla.

He also told some interesting stories about, Geoffrey Layton and Mountbatten. Saying both were playboys, he laughed. With the arrival of his son JPO. Jnr. apparently for a private and personal meeting with his father, Alex and I decided to take leave of Sir James.

I met him once more before I left Gampaha district on transfer; and this happened to be the last time. The occasion was a handicrafts exhibition at Nittambuwa. Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike was the chief guest at this exhibition and I had to accompany her as the ASP Gampaha. Most of the Members of Parliament of the area were present. I distinctly remember the tall and big made Wijayabahu Wijesinghe, Laksman Jayakody and M.P. de Z Siriwardena.

The MP for Attanagalle, J.P. Obeysekera Jr. was a notable absentee. But his father, Sir James, stood amongst the distinguished invitees. What struck me was his dress, the attire I had seen him in before; the khaki lounge suit, khaki canvas shoes and the brown felt hat.

When the Prime Minister started going round viewing the exhibits, the MPs too followed. They kept a reasonable distance from her but Sir James kept up with her talking to her all the time, even joking and laughing. The Prime Minister too appeared to enjoy his company.

One episode in which Sir James figured remains firmly etched in my memory. A large stall exhibiting terracotta statuettes drew the special attention of the Prime Minister. Prominent among these exhibits were several nude figurines. With a mischievous smile Sir James turned to the Prime Minister and to be heard by all close by commented, “Sirima, I never knew Attanagalla women had such lovely breasts!” Everybody nearby laughed. Without showing any embarrassment the Prime Minister smiled graciously.

Sir James Obeysekera was not a public figure when I met him. He was living in quiet retirement having faded away from the public gaze. From what I could gather in the limited moments I spent with him he longed for company and conversation. Having been a central figure among the social elite during the era of the Queen’s House Ball, the social evenings at the Maligawa and the Governor’s Cup the blue riband of local horse racing, loneliness had overtaken him.

I consider myself fortunate to have met this great gentleman. Undoubtedly, Sir James, the Maha Mudaliyar had been the leading aristocratic figure in the low country. But when I met him he was a simple, erudite, witty gentleman. I regret I could not attend his funeral in 1968 as I was out of The country as a Fulbright student in Michigan.

Features

Recruiting academics to state universities – beset by archaic selection processes?

Time has, by and large, stood still in the business of academic staff recruitment to state universities. Qualifications have proliferated and evolved to be more interdisciplinary, but our selection processes and evaluation criteria are unchanged since at least the late 1990s. But before I delve into the problems, I will describe the existing processes and schemes of recruitment. The discussion is limited to UGC-governed state universities (and does not include recruitment to medical and engineering sectors) though the problems may be relevant to other higher education institutions (HEIs).

How recruitment happens currently in SL state universities

Academic ranks in Sri Lankan state universities can be divided into three tiers (subdivisions are not discussed).

* Lecturer (Probationary)

– recruited with a four-year undergraduate degree. A tiny step higher is the Lecturer (Unconfirmed), recruited with a postgraduate degree but no teaching experience.

* A Senior Lecturer can be recruited with certain postgraduate qualifications and some number of years of teaching and research.

* Above this is the professor (of four types), which can be left out of this discussion since only one of those (Chair Professor) is by application.

State universities cannot hire permanent academic staff as and when they wish. Prior to advertising a vacancy, approval to recruit is obtained through a mind-numbing and time-consuming process (months!) ending at the Department of Management Services. The call for applications must list all ranks up to Senior Lecturer. All eligible candidates for Probationary to Senior Lecturer are interviewed, e.g., if a Department wants someone with a doctoral degree, they must still advertise for and interview candidates for all ranks, not only candidates with a doctoral degree. In the evaluation criteria, the first degree is more important than the doctoral degree (more on this strange phenomenon later). All of this is only possible when universities are not under a ‘hiring freeze’, which governments declare regularly and generally lasts several years.

Problem type 1

– Archaic processes and evaluation criteria

Twenty-five years ago, as a probationary lecturer with a first degree, I was a typical hire. We would be recruited, work some years and obtain postgraduate degrees (ideally using the privilege of paid study leave to attend a reputed university in the first world). State universities are primarily undergraduate teaching spaces, and when doctoral degrees were scarce, hiring probationary lecturers may have been a practical solution. The path to a higher degree was through the academic job. Now, due to availability of candidates with postgraduate qualifications and the problems of retaining academics who find foreign postgraduate opportunities, preference for candidates applying with a postgraduate qualification is growing. The evaluation scheme, however, prioritises the first degree over the candidate’s postgraduate education. Were I to apply to a Faculty of Education, despite a PhD on language teaching and research in education, I may not even be interviewed since my undergraduate degree is not in education. The ‘first degree first’ phenomenon shows that universities essentially ignore the intellectual development of a person beyond their early twenties. It also ignores the breadth of disciplines and their overlap with other fields.

This can be helped (not solved) by a simple fix, which can also reduce brain drain: give precedence to the doctoral degree in the required field, regardless of the candidate’s first degree, effected by a UGC circular. The suggestion is not fool-proof. It is a first step, and offered with the understanding that any selection process, however well the evaluation criteria are articulated, will be beset by multiple issues, including that of bias. Like other Sri Lankan institutions, universities, too, have tribal tendencies, surfacing in the form of a preference for one’s own alumni. Nevertheless, there are other problems that are, arguably, more pressing as I discuss next. In relation to the evaluation criteria, a problem is the narrow interpretation of any regulation, e.g., deciding the degree’s suitability based on the title rather than considering courses in the transcript. Despite rhetoric promoting internationalising and inter-disciplinarity, decision-making administrative and academic bodies have very literal expectations of candidates’ qualifications, e.g., a candidate with knowledge of digital literacy should show this through the title of the degree!

Problem type 2 – The mess of badly regulated higher education

A direct consequence of the contemporary expansion of higher education is a large number of applicants with myriad qualifications. The diversity of degree programmes cited makes the responsibility of selecting a suitable candidate for the job a challenging but very important one. After all, the job is for life – it is very difficult to fire a permanent employer in the state sector.

Widely varying undergraduate degree programmes.

At present, Sri Lankan undergraduates bring qualifications (at times more than one) from multiple types of higher education institutions: a degree from a UGC-affiliated state university, a state university external to the UGC, a state institution that is not a university, a foreign university, or a private HEI aka ‘private university’. It could be a degree received by attending on-site, in Sri Lanka or abroad. It could be from a private HEI’s affiliated foreign university or an external degree from a state university or an online only degree from a private HEI that is ‘UGC-approved’ or ‘Ministry of Education approved’, i.e., never studied in a university setting. Needless to say, the diversity (and their differences in quality) are dizzying. Unfortunately, under the evaluation scheme all degrees ‘recognised’ by the UGC are assigned the same marks. The same goes for the candidates’ merits or distinctions, first classes, etc., regardless of how difficult or easy the degree programme may be and even when capabilities, exposure, input, etc are obviously different.

Similar issues are faced when we consider postgraduate qualifications, though to a lesser degree. In my discipline(s), at least, a postgraduate degree obtained on-site from a first-world university is preferable to one from a local university (which usually have weekend or evening classes similar to part-time study) or online from a foreign university. Elitist this may be, but even the best local postgraduate degrees cannot provide the experience and intellectual growth gained by being in a university that gives you access to six million books and teaching and supervision by internationally-recognised scholars. Unfortunately, in the evaluation schemes for recruitment, the worst postgraduate qualification you know of will receive the same marks as one from NUS, Harvard or Leiden.

The problem is clear but what about a solution?

Recruitment to state universities needs to change to meet contemporary needs. We need evaluation criteria that allows us to get rid of the dross as well as a more sophisticated institutional understanding of using them. Recruitment is key if we want our institutions (and our country) to progress. I reiterate here the recommendations proposed in ‘Considerations for Higher Education Reform’ circulated previously by Kuppi Collective:

* Change bond regulations to be more just, in order to retain better qualified academics.

* Update the schemes of recruitment to reflect present-day realities of inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary training in order to recruit suitably qualified candidates.

* Ensure recruitment processes are made transparent by university administrations.

Kaushalya Perera is a senior lecturer at the University of Colombo.

(Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.)

Features

Talento … oozing with talent

This week, too, the spotlight is on an outfit that has gained popularity, mainly through social media.

This week, too, the spotlight is on an outfit that has gained popularity, mainly through social media.

Last week we had MISTER Band in our scene, and on 10th February, Yellow Beatz – both social media favourites.

Talento is a seven-piece band that plays all types of music, from the ‘60s to the modern tracks of today.

The band has reached many heights, since its inception in 2012, and has gained recognition as a leading wedding and dance band in the scene here.

The members that makeup the outfit have a solid musical background, which comes through years of hard work and dedication

Their portfolio of music contains a mix of both western and eastern songs and are carefully selected, they say, to match the requirements of the intended audience, occasion, or event.

Although the baila is a specialty, which is inherent to this group, that originates from Moratuwa, their repertoire is made up of a vast collection of love, classic, oldies and modern-day hits.

The musicians, who make up Talento, are:

Prabuddha Geetharuchi:

(Vocalist/ Frontman). He is an avid music enthusiast and was mentored by a lot of famous musicians, and trainers, since he was a child. Growing up with them influenced him to take on western songs, as well as other music styles. A Peterite, he is the main man behind the band Talento and is a versatile singer/entertainer who never fails to get the crowd going.

Geilee Fonseka (Vocals):

A dynamic and charismatic vocalist whose vibrant stage presence, and powerful voice, bring a fresh spark to every performance. Young, energetic, and musically refined, she is an artiste who effortlessly blends passion with precision – captivating audiences from the very first note. Blessed with an immense vocal range, Geilee is a truly versatile singer, confidently delivering Western and Eastern music across multiple languages and genres.

Chandana Perera (Drummer):

His expertise and exceptional skills have earned him recognition as one of the finest acoustic drummers in Sri Lanka. With over 40 tours under his belt, Chandana has demonstrated his dedication and passion for music, embodying the essential role of a drummer as the heartbeat of any band.

Harsha Soysa:

(Bassist/Vocalist). He a chorister of the western choir of St. Sebastian’s College, Moratuwa, who began his musical education under famous voice trainers, as well as bass guitar trainers in Sri Lanka. He has also performed at events overseas. He acts as the second singer of the band

Udara Jayakody:

(Keyboardist). He is also a qualified pianist, adding technical flavour to Talento’s music. His singing and harmonising skills are an extra asset to the band. From his childhood he has been a part of a number of orchestras as a pianist. He has also previously performed with several famous western bands.

Aruna Madushanka:

(Saxophonist). His proficiciency in playing various instruments, including the saxophone, soprano saxophone, and western flute, showcases his versatility as a musician, and his musical repertoire is further enhanced by his remarkable singing ability.

Prashan Pramuditha:

(Lead guitar). He has the ability to play different styles, both oriental and western music, and he also creates unique tones and patterns with the guitar..

Features

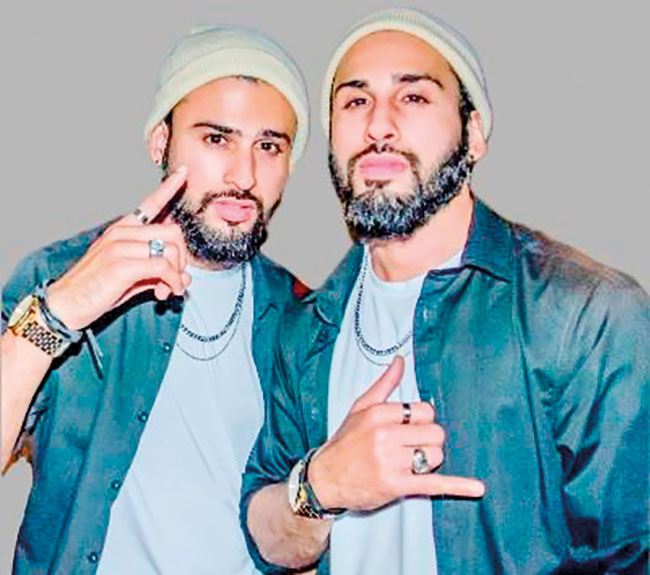

Special milestone for JJ Twins

The JJ Twins, the Sri Lankan musical duo, performing in the Maldives, and known for blending R&B, Hip Hop, and Sri Lankan rhythms, thereby creating a unique sound, have come out with a brand-new single ‘Me Mawathe.’

In fact, it’s a very special milestone for the twin brothers, Julian and Jason Prins, as ‘Me Mawathe’ is their first ever Sinhala song!

‘Me Mawathe’ showcases a fresh new sound, while staying true to the signature harmony and emotion that their fans love.

This heartfelt track captures the beauty of love, journey, and connection, brought to life through powerful vocals and captivating melodies.

It marks an exciting new chapter for the JJ Twins as they expand their musical journey and connect with audiences in a whole new way.

Their recent album, ‘CONCLUDED,’ explores themes of love, heartbreak, and healing, and include hits like ‘Can’t Get You Off My Mind’ and ‘You Left Me Here to Die’ which showcase their emotional intensity.

Readers could stay connected and follow JJ Twins on social media for exclusive updates, behind-the-scenes moments, and upcoming releases:

Instagram: http://instagram.com/jjtwinsofficial

TikTok: http://tiktok.com/@jjtwinsmusic

Facebook: http://facebook.com/jjtwinssingers

YouTube: http://youtube.com/jjtwins

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoJamming and re-setting the world: What is the role of Donald Trump?

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoAn innocent bystander or a passive onlooker?

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoBrilliant Navy officer no more

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoRatmalana Airport: The Truth, The Whole Truth, And Nothing But The Truth

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoDialog partners with Xiaomi to introduce Redmi Note 15 5G Series in Sri Lanka

-

Features7 days ago

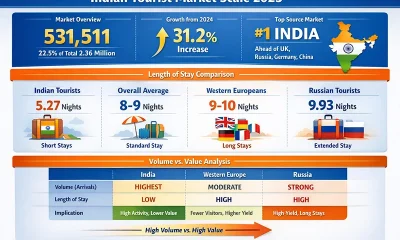

Features7 days agoBuilding on Sand: The Indian market trap

-

Opinion7 days ago

Opinion7 days agoFuture must be won

-

Opinion2 days ago

Opinion2 days agoSri Lanka – world’s worst facilities for cricket fans