Opinion

Living with Lenin and Risking HELL

The name was a conversation piece. He was known as ‘Lenin,’ but that was actually an afterthought. Born Hirohito Edward Jayasinghe to a radical communist—Jones Alexander Jayasinghe—and his Eurasian bride, Myra Nesta Crutchley, my father underwent a name substitution just two days before his first birthday in October 1937. His parents dropped “Hirohito Edward” and replaced it with ‘Lenin’ and ‘Lindbergh.’

What was Lenin like? How did he influence his family and friends? Did he follow the great Russian leader? For much of his life, he was sympathetic to the communist state. He embraced leftist trade union activism throughout his career in the postal department. He also became a defence counsel, a legal representative for public servants facing disciplinary action and built a considerable practice. In the true socialist spirit, his services were free—the only fee was the ‘batta,’ the official stipend, he collected as a public servant and a huge reservoir of goodwill.

My brother, Lakal, and I grew up in a home imbued with egalitarian values. The most impressionable time of our childhood was during Mrs Bandaranaike’s rationing regime when each household had ration books—one per person. Among other items, everyone was entitled to a quarter pound (100 grams) of sugar a month. Lenin was a true leftist and embraced the bitter austerity as a necessary hell for a better future.

Early in their marriage, my mother, Latha, feared that Lenin would use all his names in the order they were given—Hirohito Edward Lenin Lindbergh (HELL). Theirs was a love marriage made in heaven, but ‘HELL’ being part of it was not what my mother had bargained for—or so she told us.

My father became better known by his new first name, Lenin. On his first birthday, he was photographed wearing a beret adorned with the hammer and sickle, the symbol of the world communist movement. This was considered an act of defiance at a time when communists were not tolerated in British-ruled Ceylon. That was six years before the launch of the Communist Party of Ceylon in 1943. Jones Alexander Jayasinghe was reportedly arrested for defying the colonial authorities. How he escaped trouble is unclear, but family photos place Jones Alexander in the company of many figures at the forefront of Ceylon’s independence movement. Jones Alexander was a friend of the then-young Pieter Keuneman, who went on to become the Secretary of the Communist Party of Ceylon as well as trade union stalwart H. G. S. Ratnaweera.

Lenin was initially named ‘Hirohito,’ apparently because my grandfather admired the Japanese emperor. I have been unable to verify claims that he was among the first to use a Japanese-made Datsun model ‘DB,’ a 722 cc petrol-powered car that was infamous for its lack of reliability, unlike the Western-made vehicles dominating the British Empire at the time. The second name, Edward, honoured the UK’s King Edward VIII, who had ascended the throne in January 1936, ten months before my father was born. The two later names, Lenin and Lindbergh, were substituted a year later, though the reasons for this change remain unclear.

This was likely because Jones Alexander Jayasinghe had begun to rebel against colonial rule and opposed imperial Japan. The substituted names reflected his leanings towards Red Russia and the global human interest story of Charles Lindbergh after the murder of his baby. The name ‘Lindbergh’ referred to the American aviator who completed the first solo transatlantic flight in his aircraft, Spirit of St. Louis. The kidnapping and subsequent murder of Lindbergh’s 20-month-old son in 1932 had shocked the world and was widely known in Ceylon at the time of my father’s birth four years later.

My mother may also be the exception that proved the rule that marriage won’t make a man change. A promise to give up alcohol if she married him was kept, and Lenin never touched spirits—until I cajoled him into enjoying a glass of white wine. Giving up alcohol underscored my mother’s spirited determination to instil some discipline in him. A nasty motorcycle accident that saw him flying over the Dehiwala roundabout and narrowly escaping death shortly before his wedding may also have contributed to his temperance.

However, my father’s greatest failing was his inability to give up smoking. Unable to make him quit cigarettes, my mother, in a tit-for-tat move, threatened to cut off her long hair—something my father was ready to accept in exchange for continuing to smoke two to three packets of ‘Three Roses,’ the popular filter-less cigarettes, daily. After a life-changing heart bypass surgery in 1999, he finally gave up chain-smoking—at least in public.

Lenin’s heart and kidney-related health issues later in life were blamed on cigarettes. Neither my brother nor I developed any interest in smoking or drinking.

With my father being a postmaster and my mother a mathematics teacher, we learned to be frugal and count our blessings. Given the country’s economic circumstances at the time, with import restrictions being the norm, there was little pressure to buy things and no one was spoilt for choice. Most Sri Lankans endured the same miseries. Replacing a headlamp on my father’s old English motorcycle, which he had bought second-hand before his marriage, required hours in a queue at the State Trading Corporation. Even then, it was only possible after collecting approvals from several local officials to prove that the Velocette MAC motorcycle had a fused headlamp.

Even in tough times, my parents instilled in us the importance of helping others and sharing—a practice they continued until their dying days. I also owe my driving skills to my father, who would place me on the petrol tank of the 350cc single-cylinder motorcycle and let me take the controls when I was just 10 years old. Two decades later, he repeated this with my son, Navin on a newer, faster Honda 250N. After an accident that resulted in both my parents fracturing their limbs, my father reluctantly gave up his beloved two-wheelers for the safety of four wheels, though he was never comfortable driving cars.

Looking back, I am amazed at how I used to sneak out the heavy motorcycle for joyrides, even when both my feet couldn’t reach the ground. But those were quieter times when there were few private vehicles on the road, and a 10-year-old on a motorcycle didn’t pose much risk to himself or others.

As the younger of two sons, I rebelled by pursuing a career path that did not align with my teacher mother’s expectations of academic excellence. “My youngest son is a reporter at the Daily News, but my other son is a graduate,” she would tell her friends and colleagues, underscoring both her disappointment and pride simultaneously. But as years passed and I became a foreign correspondent, she came to terms with her youngest son’s high-risk but low-paying career, taking comfort in an astrologer’s not entirely accurate prediction that I would be a “writer known overseas.” Even after her retirement, she continued to teach neighbourhood children as part of her social work until Lenin’s passing in January 2018. With her beloved partner gone, she steadily declined and passed away in her sleep three years later on November 15, 2021.

On 10 January 2025, we marked the seventh death anniversary of Lenin Lindbergh Jayasinghe – a steadfast egalitarian, dedicated public servant, and a man whose influence left an indelible mark on all who knew him.

Amal Jayasinghe

Opinion

Are we reading the sky wrong?

Rethinking climate prediction, disasters, and plantation economics in Sri Lanka

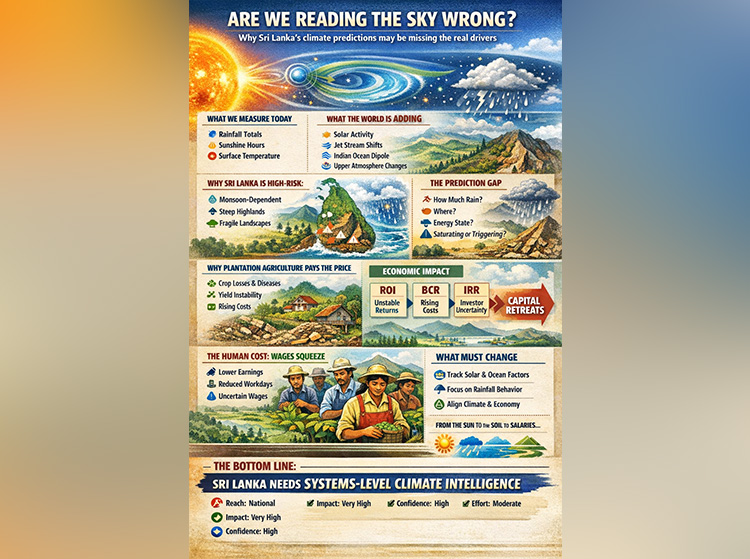

For decades, Sri Lanka has interpreted climate through a narrow lens. Rainfall totals, sunshine hours, and surface temperatures dominate forecasts, policy briefings, and disaster warnings. These indicators once served an agrarian island reasonably well. But in an era of intensifying extremes—flash floods, sudden landslides, prolonged dry spells within “normal” monsoons—the question can no longer be avoided: are we measuring the climate correctly, or merely measuring what is easiest to observe?

Across the world, climate science has quietly moved beyond a purely local view of weather. Researchers increasingly recognise that Earth’s climate system is not sealed off from the rest of the universe. Solar activity, upper-atmospheric dynamics, ocean–atmosphere coupling, and geomagnetic disturbances all influence how energy moves through the climate system. These forces do not create rain or drought by themselves, but they shape how weather behaves—its timing, intensity, and spatial concentration.

Sri Lanka’s forecasting framework, however, remains largely grounded in twentieth-century assumptions. It asks how much rain will fall, where it will fall, and over how many days. What it rarely asks is whether the rainfall will arrive as steady saturation or violent cloudbursts; whether soils are already at failure thresholds; or whether larger atmospheric energy patterns are priming the region for extremes. As a result, disasters are repeatedly described as “unexpected,” even when the conditions that produced them were slowly assembling.

This blind spot matters because Sri Lanka is unusually sensitive to climate volatility. The island sits at a crossroads of monsoon systems, bordered by the Indian Ocean and shaped by steep central highlands resting on deeply weathered soils. Its landscapes—especially in plantation regions—have been altered over centuries, reducing natural buffers against hydrological shock. In such a setting, small shifts in atmospheric behaviour can trigger outsized consequences. A few hours of intense rain can undo what months of average rainfall statistics suggest is “normal.”

Nowhere are these consequences more visible than in commercial perennial plantation agriculture. Tea, rubber, coconut, and spice crops are not annual ventures; they are long-term biological investments. A tea bush destroyed by a landslide cannot be replaced in a season. A rubber stand weakened by prolonged waterlogging or drought stress may take years to recover, if it recovers at all. Climate shocks therefore ripple through plantation economics long after floodwaters recede or drought declarations end.

From an investment perspective, this volatility directly undermines key financial metrics. Return on Investment (ROI) becomes unstable as yields fluctuate and recovery costs rise. Benefit–Cost Ratios (BCR) deteriorate when expenditures on drainage, replanting, disease control, and labour increase faster than output. Most critically, Internal Rates of Return (IRR) decline as cash flows become irregular and back-loaded, discouraging long-term capital and raising the cost of financing. Plantation agriculture begins to look less like a stable productive sector and more like a high-risk gamble.

The economic consequences do not stop at balance sheets. Plantation systems are labour-intensive by nature, and when financial margins tighten, wage pressure is the first stress point. Living wage commitments become framed as “unaffordable,” workdays are lost during climate disruptions, and productivity-linked wage models collapse under erratic output. In effect, climate misprediction translates into wage instability, quietly eroding livelihoods without ever appearing in meteorological reports.

This is not an argument for abandoning traditional climate indicators. Rainfall and sunshine still matter. But they are no longer sufficient on their own. Climate today is a system, not a statistic. It is shaped by interactions between the Sun, the atmosphere, the oceans, the land, and the ways humans have modified all three. Ignoring these interactions does not make them disappear; it simply shifts their costs onto farmers, workers, investors, and the public purse.

Sri Lanka’s repeated cycle of surprise disasters, post-event compensation, and stalled reform suggests a deeper problem than bad luck. It points to an outdated model of climate intelligence. Until forecasting frameworks expand beyond local rainfall totals to incorporate broader atmospheric and oceanic drivers—and until those insights are translated into agricultural and economic planning—plantation regions will remain exposed, and wage debates will remain disconnected from their true root causes.

The future of Sri Lanka’s plantations, and the dignity of the workforce that sustains them, depends on a simple shift in perspective: from measuring weather, to understanding systems. Climate is no longer just what falls from the sky. It is what moves through the universe, settles into soils, shapes returns on investment, and ultimately determines whether growth is shared or fragile.

The Way Forward

Sustaining plantation agriculture under today’s climate volatility demands an urgent policy reset. The government must mandate real-world investment appraisals—NPV, IRR, and BCR—through crop research institutes, replacing outdated historical assumptions with current climate, cost, and risk realities. Satellite-based, farm-specific real-time weather stations should be rapidly deployed across plantation regions and integrated with a central server at the Department of Meteorology, enabling precision forecasting, early warnings, and estate-level decision support. Globally proven-to-fail monocropping systems must be phased out through a time-bound transition, replacing them with diversified, mixed-root systems that combine deep-rooted and shallow-rooted species, improving soil structure, water buffering, slope stability, and resilience against prolonged droughts and extreme rainfall.

In parallel, a national plantation insurance framework, linked to green and climate-finance institutions and regulated by the Insurance Regulatory Commission, is essential to protect small and medium perennial growers from systemic climate risk. A Virtual Plantation Bank must be operationalized without delay to finance climate-resilient plantation designs, agroforestry transitions, and productivity gains aligned with national yield targets. The state should set minimum yield and profit benchmarks per hectare, formally recognize 10–50 acre growers as Proprietary Planters, and enable scale through long-term (up to 99-year) leases where state lands are sub-leased to proven operators. Finally, achieving a 4% GDP contribution from plantations requires making modern HRM practices mandatory across the sector, replacing outdated labour systems with people-centric, productivity-linked models that attract, retain, and fairly reward a skilled workforce—because sustainable competitive advantage begins with the right people.

by Dammike Kobbekaduwe

(www.vivonta.lk & www.planters.lk ✍️

Opinion

Disasters do not destroy nations; the refusal to change does

Sri Lanka has endured both kinds of catastrophe that a nation can face, those caused by nature and those created by human hands. A thirty-year civil war tore apart the social fabric, deepening mistrust between communities and leaving lasting psychological wounds, particularly among those who lived through displacement, loss, and fear. The 2004 tsunami, by contrast, arrived without warning, erasing entire coastal communities within minutes and reminding us of our vulnerability to forces beyond human control.

These two disasters posed the same question in different forms: did we learn, and did we change? After the war ended, did we invest seriously in repairing relationships between Sinhalese and Tamil communities, or did we equate peace with silence and infrastructure alone? Were collective efforts made to heal trauma and restore dignity, or were psychological wounds left to be carried privately, generation after generation? After the tsunami, did we fundamentally rethink how and where we build, how we plan settlements, and how we prepare for future risks, or did we rebuild quickly, gratefully, and then forget?

Years later, as Sri Lanka confronts economic collapse and climate-driven disasters, the uncomfortable truth emerges. we survived these catastrophes, but we did not allow them to transform us. Survival became the goal; change was postponed.

History offers rare moments when societies stand at a crossroads, able either to restore what was lost or to reimagine what could be built on stronger foundations. One such moment occurred in Lisbon in 1755. On 1 November 1755, Lisbon-one of the most prosperous cities in the world, was almost completely erased. A massive earthquake, estimated between magnitude 8.5 and 9.0, was followed by a tsunami and raging fires. Churches collapsed during Mass, tens of thousands died, and the royal court was left stunned. Clergy quickly declared the catastrophe a punishment from God, urging repentance rather than reconstruction.

One man refused to accept paralysis as destiny. Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, later known as the Marquês de Pombal, responded with cold clarity. His famous instruction, “Bury the dead and feed the living,” was not heartless; it was revolutionary. While others searched for divine meaning, Pombal focused on human responsibility. Relief efforts were organised immediately, disease was prevented, and plans for rebuilding began almost at once.

Pombal did not seek to restore medieval Lisbon. He saw its narrow streets and crumbling buildings as symbols of an outdated order. Under his leadership, Lisbon was rebuilt with wide avenues, rational urban planning, and some of the world’s earliest earthquake-resistant architecture. Moreover, his vision extended far beyond stone and mortar. He reformed trade, reduced dependence on colonial wealth, encouraged local industries, modernised education, and challenged the long-standing dominance of aristocracy and the Church. Lisbon became a living expression of Enlightenment values, reason, science, and progress.

Back in Sri Lanka, this failure is no longer a matter of opinion. it is documented evidence. An initial assessment by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) following Cyclone Ditwah revealed that more than half of those affected by flooding were already living in households facing multiple vulnerabilities before the cyclone struck, including unstable incomes, high debt, and limited capacity to cope with disasters (UNDP, 2025). The disaster did not create poverty; it magnified it. Physical damage was only the visible layer. Beneath it lay deep social and economic fragility, ensuring that for many communities, recovery would be slow, uneven, and uncertain.

The world today offers Sri Lanka another lesson Lisbon understood centuries ago: risk is systemic, and resilience cannot be improvised, it must be planned. Modern climate science shows that weather systems are deeply interconnected; rising ocean temperatures, changing wind patterns, and global emissions influence extreme weather far beyond their points of origin. Floods, landslides, and cyclones affecting Sri Lanka are no longer isolated events, but part of a broader climatic shift. Rebuilding without adapting construction methods, land-use planning, and infrastructure to these realities is not resilience, it is denial. In this context, resilience also depends on Sri Lanka’s willingness to learn from other countries, adopt proven technologies, and collaborate across borders, recognising that effective solutions to global risks cannot be developed in isolation.

A deeper problem is how we respond to disasters: we often explain destruction without seriously asking why it happened or how it could have been prevented. Time and again, devastation is framed through religion, fate, karma, or divine will. While faith can bring comfort in moments of loss, it cannot replace responsibility, foresight, or reform. After major disasters, public attention often focuses on stories of isolated religious statues or buildings that remain undamaged, interpreted as signs of protection or blessing, while far less attention is paid to understanding environmental exposure, construction quality, and settlement planning, the factors that determine survival. Similarly, when a single house survives a landslide, it is often described as a miracle rather than an opportunity to study soil conditions, building practices, and land-use decisions. While such interpretations may provide emotional reassurance, they risk obscuring the scientific understanding needed to reduce future loss.

The lesson from Lisbon is clear: rebuilding a nation requires the courage to question tradition, the discipline to act rationally, and leadership willing to choose long-term progress over short-term comfort. Until Sri Lanka learns to rebuild not only roads and buildings, but relationships, institutions, and ways of thinking, we will remain a country trapped in recovery, never truly reborn.

by Darshika Thejani Bulathwatta

Psychologist and Researcher

Opinion

A wise Christmas

Important events in the Christian calendar are to be regurlarly reviewed if they are to impact on the lives of people and communities. This is certainly true of Christmas.

Community integrity

Years ago a modest rural community did exactly this, urging a pre-Christmas probe of the events around Jesus’ birth. From the outset, the wisemen aroused curiosity. Who were these visitors? Were they Jews? No. were they Christians? Of course not. As they probed the text, the representative character of those around the baby, became starkly clear. Apart from family, the local shepherds and the stabled animals, the only others present that first Christmas, were sages from distant religious cultures.

With time, the celebration of Christmas saw a sharp reversal. The church claimed exclusive ownership of an inclusive gift and deftly excluded ‘outsiders’ from full participation.

But the Biblical version of the ‘wise outsiders’ remained. It affirmed that the birth of Jesus inspired the wise to initiate a meeting space for diverse religious cultures, notwithstanding the long and ardous journey such initiatives entail. Far from exclusion, Jesus’ birth narratives, announced the real presence of the ‘outsider’ when the ‘Word became Flesh’.

The wise recognise the gift of life as an invitation to integrate sincere explanations of life; true religion. Religion gone bad, stalls these values and distorts history.

There is more to the visit of these sages.

Empire- When Jesus was born, Palestine was forcefully occcupied by the Roman empire. Then as now, empire did not take kindly to other persons or forces that promised dignity and well being. So, when rumours of a coming Kingdom of truth, justice and peace, associated with the new born baby reached the local empire agent, a self appointed king; he had to deliver. Information on the wherabouts of the baby would be diplomatically gleaned from the visiting sages.

But the sages did not only read the stars. They also read the signs of the times. Unlike the local religious authorities who cultivated dubious relations with a brutal regime hated by the people, the wise outsiders by-pass the waiting king.

The boycott of empire; refusal to co-operate with those who take what it wills, eliminate those it dislikes and dare those bullied to retaliate, is characteristic of the wise.

Gifts of the earth

A largely unanswered question has to do with the gifts offered by the wise. What happened to these gifts of the earth? Silent records allow context and reason to speak.

News of impending threats to the most vulnerable in the family received the urgent attention of his anxious parent-carers. Then as it is now, chances of survival under oppressive regimes, lay beyond borders. As if by anticipation, resources for the journey for asylum in neighbouring Egypt, had been provided by the wise. The parent-carers quietly out smart empire and save the saviour to be.

Wise carers consider the gifts of the earth as resources for life; its protection and nourishment. But, when plundered and hoarded, resources for all, become ‘wealth’ for a few; a condition that attempts to own the seas and the stars.

Wise choices

A wise christmas requires that the sages be brought into the centre of the discourse. This is how it was meant to be. These visitors did not turn up by chance. They were sent by the wisdom of the ages to highlight wise choices.

At the centre, the sages facilitate a preview of the prophetic wisdom of the man the baby becomes.The choice to appropriate this prophetic wisdom has ever since summed up Christmas for those unable to remain neutral when neighbour and nature are violated.

Wise carers

The wisdom of the sages also throws light on the life of our nation, hard pressed by the dual crises of debt repayment and post cyclonic reconstruction. In such unrelenting circumstances, those in civil governance take on an additional role as national carers.

The most humane priority of the national carer is to ensure the protection and dignity of the most vulnerable among us, immersed in crisis before the crises. Better opportunities, monitored and sustained through conversations are to gradually enhance the humanity of these equal citizens.

Nations in economic crises are nevertheless compelled to turn to global organisations like the IMF for direction and reconstruction. Since most who have been there, seldom stand on their own feet, wise national carers may not approach the negotiating table, uncritically. The suspicion, that such organisations eventually ‘grow’ ailing nations into feeder forces for empire economics, is not unfounded.

The recent cyclone gave us a nasty taste of these realities. Repeatedly declared a natural disaster, this is not the whole truth. Empire economics which indiscriminately vandalise our earth, had already set the stage for the ravage of our land and the loss of loved ones and possessions. As always, those affected first and most, were the least among us.

Unless we learn to manouvre our dealings for recovery wisely; mindful of our responsibilities by those relegated to the margins as well as the relentles violence and greed of empire, we are likely to end up drafted collaborators of the relentless havoc against neighbour and nature.

If on the other hand the recent and previous disasters are properly assessed by competent persons, reconstruction will be seen as yet another opportunity for stabilising content and integrated life styles for all Lankans, in some harmony with what is left of our dangerously threatened eco-system. We might then even stand up to empire and its wily agents, present everywhere. Who knows?

With peace and blessings to all!

Bishop Duleep de Chickera

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoMembers of Lankan Community in Washington D.C. donates to ‘Rebuilding Sri Lanka’ Flood Relief Fund

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoBritish MP calls on Foreign Secretary to expand sanction package against ‘Sri Lankan war criminals’

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoBrowns Investments sells luxury Maldivian resort for USD 57.5 mn.

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoAir quality deteriorating in Sri Lanka

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoCardinal urges govt. not to weaken key socio-cultural institutions

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoHatton Plantations and WNPS PLANT Launch 24 km Riparian Forest Corridor

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoAnother Christmas, Another Disaster, Another Recovery Mountain to Climb

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoGeneral education reforms: What about language and ethnicity?