Features

Getting a break into tea tasting, a short stint at Mobil and then back to tea

Learning the ropes amd acquiring new tastes in London

Excerpted from the autobiography of Merril J. Fernando

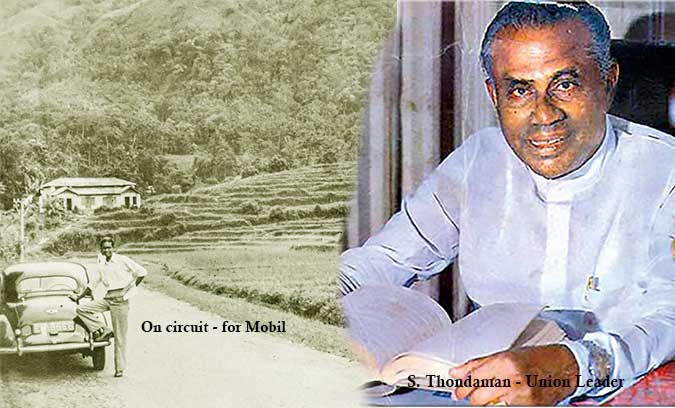

In my youth I was very fortunate in having been able to spend the occasional holiday on tea estates of affluent friends. Those interludes were my first introduction to tea but, at that time, it never occurred to me that later in life my fortunes would be so greatly influenced by plantations and their product. I spent time on estates in the Pundaluoya and Kotmale Districts, belonging to K. R. Mathavan and his brothers, Karuppiah and Arumugam, as well as their uncle, S. Thondaman, later President of the very powerful Ceylon Workers’ Congress and Cabinet Minister of two governments.

Notwithstanding their wealth and influence, they were very nice and simple people. Those visits gave me an early exposure to the cultivation and manufacture of tea. I also became familiar with the role of the plantation workers and their lives. Their dedication and commitment to work, despite the difficult conditions they worked under, left a lasting impression on me. What I observed then, especially the unrelentingly-demanding lives of the plantation workers and their very basic living conditions, influenced the many initiatives I was able to launch for their welfare, when I acquired the resources to do so later on in life.

My ambition at that stage of my life was to enter Law College and become a lawyer, to defend innocent people charged for crimes which they did not commit. But fate decided otherwise and diverted me from this idealistic vision.

A unique opportunity

Soon after I passed my Senior School Certificate examination, whilst I was preparing to enter Law College, I learned that the Tea Controller was proposing to recruit a few local young men for training in tea tasting, under the Government Tea Taster, O. P. Rust, then Managing Director of Darley Butler & Co. Ltd. Britishers, who dominated the tea business then, were of the firm view that locals did not have the palate to make good tea tasters, as they ate too much spicy food!

My interest was aroused, as this opportunity arose soon after one of my plantation holidays and, hence, I decided to apply. The decision to train locals in tea tasting was a reluctant response by the British tea firms then operating in Colombo to numerous requests made to them, over several years, by the Government of Ceylon. At that time the Tea Commissioner was P. Saravanamuttu, who had also exerted much pressure on these companies to open their closely-guarded field to locals.

In the mid-1940s the Tea Commissioner’s Department had trained a few Ceylonese – Lionel Cooray, Errol de Fonseka, Austin Perera, and Mahinda Wijesekera – as tea tasters but with the end of World War II and the return of Britishers to pre-war civilian occupations in the country, the doors were once again firmly closed to locals. There are also reliable reports that this pioneer group of Ceylonese tea tasters had been subjected to open resentment by some of their European colleagues.

In contrast to their jealous protection of tea tasting as a private British preserve, the almost-entirely British-controlled plantation management firms had started recruiting Ceylonese youth to the plantations at least a decade earlier. Of course, there was a great element of compulsion behind that move as well, as with the onset of World War II, a large number of British planters had left the plantations to join the overseas British forces.

Many of them did not return and, in the interim, most of the management vacancies on estates had to be filled by Ceylonese youth. That apart, with the release of the colonies from the British Empire being an early possibility, following the granting of independence to India, Ceylon was no longer as attractive as it used to be, to young Britishers looking for a life of both adventure and well-paid comfort in a British dominion. As a result of the high exodus and low influx of expatriates over the two decades post-Independence, most of the key positions in the plantation sector and allied interests came to be occupied by local executives.

The British masters of the industry would have also soon realised that the latter were capable of delivering results as efficiently, and at a much lower cost, than their British predecessors.

The Tea Controller, A. O. (“Gusty”) Weerasinghe, was an old boy of St. Peter’s College. Fr. D. J. Nicholas Perera, my former teacher and benefactor, had been the Rector of St. Peter’s for some years and I asked him whether he knew Mr. Weerasinghe and, if so, would he help.

The good Reverend, at that time Director of the St. Aloysius Seminary, almost immediately provided the necessary introduction, along with a very complimentary letter of recommendation. Thus, in the latter part of 1950, I commenced my training as a tea taster, along with a few other local trainees – Channa Gunasekera, Oscar Dalpathado, Patrick Pereira, and S. Shanmugarajah, as the second group of `natives’ to break into this exclusive preserve.

Thereafter, the numbers of Ceylonese entering the tea tasting profession steadily increased, due mainly to the gradual retirement of expatriates occupying senior positions in the tea broking and tea exporting companies, as well as in the estate agency houses.

Of my co-trainees, Channa enjoyed a long and successful career as a tea-taster and buyer, I believe almost entirely with Brooke Bond till retirement, whilst “Sam” Shanmugarajah, after a spell with Rowley Davies, and thereafter Carsons, also moved across to Brookes. Apart from being a respected tea man, Channa was also a famous cricketer, representing the then ‘All Ceylon’ team on many occasions.

Entrepreneurship – an early lesson

Whilst I was undergoing training, I realized the need to support myself and at this juncture, my connections with the Mathavan family came in handy. With the little knowledge of tea I was gaining as a trainee tea taster, I started a small tea business by supplying bulk tea to retail shops and restaurants in and around Negombo, with tea bought from Medetenne and Meddeloya Estates, Kotmale, owned by the Thondaman/Mathavan family group.

I also bought from private auctions. I sold at an average of about Rs. 2 per pound and made a profit of around 20 cents per pound, selecting my tea carefully, ensuring that what I delivered to my customers was of consistent quality. Consequently, many of the retailers I approached had no hesitation in leaving their previous suppliers and switching to me. That was my very first and, without doubt, most valuable practical lesson in marketing — that the customer is prepared to pay a decent price for genuine quality, provided that the supplier ensures consistency of the product. The proceeds enabled me to pay the installments on a brand new Morris Minor, my first car.

Mr. Rust was a great teacher, extremely patient and tolerant. After my initial training, I was very fortunate in continuing my indoctrination in tea at Heath & Co, which was the largest exporter of tea at that time. It dominated exports to Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, South Africa, and Iraq. Two dynamic Partners, A. G. (Sandy) Mathewson, an Englishman, and Stan J. Campbell, an Australian. owned the company then.

Whilst I was under training at Heath, I was also interviewed by Hamilton H. Gourlay, then Senior Partner of George Steuart & Co., the leading estate agency house in the country, for a position in its tea department. Sandy Mathewson very kindly provided me with a recommendation. However, another candidate, J. F. A. Peries, was selected. He was the first local recruit as an executive to GS & Co and, subsequently, became its first local Board member and first Sri Lankan Chairman.

At the time of his recruitment, GS & Co was a private partnership, with all members being expatriates. Peries’s recruitment too would have been a reluctant concession by the British rulers of commerce in Ceylon, to the need for gradual Ceylonisation of management, commencing at the bottom rung.

In his memoir, ‘A Personal Odyssey,’ Peries writes that Brian Van Houten of the ‘Times of Ceylon’ had also been interviewed at the same time, for the same position.

“Tony,” as he was better known, modestly attributes his selection to better connections. He became my friend later on and, after some initial opposition, was helpful in my securing membership in the Ceylon Tea Propaganda Board, an episode I will recount later on this writing.

A change of direction

Mr. Mathewson took me under his direct care in the tasting room. After a year’s training, he asked me if I would like to go to London and be trained at J. L. Lyons, the then UK tea giant. I immediately agreed and he set about making the necessary travel arrangements. My application for a trainee’s position in London was also supported by a recommendation, in the form of a personal letter from John Black, then Director, Somerville and Co., addressed to Rae Culverhouse, Director of Ridgways, UK, a tea firm in business since 1836.

Whilst all this was going on, there was another unexpected development in my life. My uncle Victor Salgado, who operated a successful car sales business in Kurana, Negombo, took me to see his friend Sam Selviah, who was then a Senior Executive at Standard Vacuum Oil Company (Mobil). I had no idea that I was being taken for an employment interview, until I met Messrs. Selviah and Sam Strassberger, also of the same company!

On conclusion of the meeting, or interview, I was offered a job as Retail Merchandising Assistant, reporting to C. A. Kelso, an American marketing specialist, who would train me over the next three months. The terms were quite attractive, a salary of Rs. 250 per month, coupled with a living allowance, as well as a mileage allowance for using my own car for travel, amounting to Rs. 1,500 per month, approximately.

The offer was too tempting to turn down and, at 22 years of age, displaying what I later realized to be a distressing lack of responsibility in suddenly abandoning my trainee tea taster programme, I immediately accepted.

I knew that my decision to suddenly leave Heath and Co would be a great disappointment to Mr. Mathewson, who had extended such goodwill to me. Therefore I did not discuss the matter with him, beforehand. The other factor which influenced my decision to accept the Mobil offer was that, despite the training we were being given as tea tasters, it was still a field that the British tea company owners considered a private preserve. Regardless of the training, access to the trade was not assured. Ceylon had achieved Independence a couple of years earlier but, still, our colonial masters owned and wrote the rule book.

From the very beginning I enjoyed my work as a Merchandising Assistant at Mobil Oil, which required me to fix my own programme to travel throughout the country, visiting gas stations. After one year in the role, I was offered the important position of Regional Inspector, actually a different title for a Regional Sales Representative, covering a vast area, from Colombo across to the North Central Province. This role carried the authority for establishing, in competition with Shell and Caltex oil companies, new fuel distribution stations, for which there was a rapidly-growing demand.

I was very successful from the beginning as I had very good contacts, both friends and relatives. In some cases, I was able to persuade potential customers to break away from existing contracts with the other two competitors. However, I soon realized that this business was open to and driven by bribery. Potential investors in Mobil petrol stations and service stations had to offer bribes to company inspectors. I was offered money to approve these investments, when I should, in fact, be incentivizing them instead.

I refused to accept such gratifications and picked investors entirely on merit. When new filling stations were eventually opened, the owners would again offer me money which I never accepted, pointing out that they were doing me a favour and that I should be grateful to them for the business. My conscience did not permit me to accept gifts or other rewards from clients, for doing the job for which I was being paid a regular salary by my employer.

Re-entering the tea trade – A. F. Jones

Within a short time after commencing my assignment with Mobil, I began to have differences of opinion with my colleagues. The impression had been created that I was not a team player. A primary reason for this friction was my firm refusal to accept any type of unregulated financial benefit in connection with my professional business transactions with clients. Unfortunately, the practice seemed to be entrenched in the system.

Eventually, because of the open displays of dislike and disapproval from other company men, which made my life unpleasant, I decided to leave Mobil and look around for an opening elsewhere, preferably in tea. Despite my somewhat precipitate departure from the earlier tea tasting training programme, Sandy Mathewson of Heath & Co again provided me with a good reference. Eventually I was called for an interview by A. F. Jones & Co. Ltd, and recruited as a Junior Tea Assistant on August 19, 1954. I was confirmed in that position on April 29, 1955, at a salary of Rs. 750 per month. A condition of my appointment was that I go for further training to London, at my own expense.

A. F. Jones was a small family business owned by A. F. Jones, the father, and the two sons, Dennis and Alan. There were two other Englishmen — a brilliant tea expert in Terrence Alan and a competent Finance Manager in Geoff Law. After a few months of coaching in Colombo I left for London to work with Joseph Travers Ltd., 119, Cannon Street, London EC4, a short distance from Mincing Lane, which was the Tea Centre of the World then.

London – maiden overseas visit

My first visit to London, which was also my first overseas trip, was in the winter of 1954, traveling in the ‘SS Himalaya,’ on its maiden voyage from Australia to London. I paid 92 pounds for a single berth, tourist class cabin. It was a very pleasant journey, during which I made friends with several Australian girls, fellow passengers, two of whom I corresponded with for several years. The Himalaya touched at the port of Aden, where, in a bazaar on the waterfront, I purchased two nice sweaters for 10 shillings each, delighted at what seemed to be a great bargain.

The next stop was Port Said and then on to Tilbury, England. We docked at 1 p.m. but it seemed to be dark enough for the time to be 1 a.m. My friends on the ship pointed out to this bemused first timer that it was winter in England! My good school friend Moritz Fernando, then an accountant in a British firm, accompanied by Ronnie Peiris, a Ceylonese living in London, met me at the Tilbury docks and brought me to London. I was mortally scared of navigating the escalators at tube stations, contraptions which I had not seen before. Moritz had to hold my hand initially, until I got over my fear.

I rented a basement flat at 7, Kensington Place at 2.10 pounds per week. My landlady was the widowed Ms. L. M. Butler, whose husband had been an Army officer, killed in action in World War II. She was a very devout Christian who made certain that I accompanied her to Holy Mass every Sunday and on the first Friday of the month, at St. Teresa’s Carmelite Church, a short distance away.

There was an adjoining flat to mine and the two had a common bathroom and toilet. On the second day after my arrival in London, I enjoyed a nice warm bath and sat in front of the gas fire in my living room reading the newspapers. I soon heard a knock at the door and an irate lady, Ms. Faskin, who shared Mrs. Butler’s flat, appeared in the doorway and accused me of having used her bathwater. That day, I learned that I had to wash the bathtub and fill it myself. I did not make that mistake again.

I also discovered that the two sweaters I purchased in Aden had only the front but no back! Therefore, I was compelled to buy two sweaters in London at 10 pounds each. It was an early lesson that cheap things come at a price! I also bought myself a black suit for seven pounds, a duffle coat for five pounds and a few white shirts with detachable collars, which enabled washing off the black soot from the smog. When I finally left London I sold my black suit for five pounds and the coat for three pounds.

I used to travel by underground train from Notting Hill Gate to Bank Station for work, paying nine pence each way. Russell Shaw, Chairman of Joseph Travers & Sons Limited, and all its staff welcomed me and cared for me right through my stay in London. With the first snowfall in London, I rushed outside to see snow and staff members helped me to make snowballs. My thoughts went back to my school days, when I read about the ‘snowman’. I experienced a childish delight in my first encounter with snow!

At Joseph Travers & Sons Ltd., I was paid the princely sum of four pounds per week and staff members were provided lunch daily, for a weekly payment of two pounds. Several senior staff members invited me to their homes for frequent Sunday lunches and the traveling involved enabled me to visit many of the suburbs of London.

The Manager of the Tea Department was J. S. Boyce, a very kind gentleman who showed genuine concern about my personal welfare. I worked directly under J. R. Keyt, who spent much time teaching me about both the UK trade as well as their overseas export trade operations. My colleague was D. V. Baldock. Every day, during the tea break we had a cup of coffee together, at nine pence a cup.

Once I developed a bad toothache whilst at work. Mr. Boyce took me to Guys Hospital, which was also a well-known teaching hospital with an attached medical college. The dentist on duty at the time of my admission decided that an extraction was necessary and struggled, without success, with my aching tooth for over an hour. Then another dentist, a lady, was called in, who admitted that the previous doctor was actually a student, and obviously inexperienced. However, she too had a hard time with the extraction, grumbling that Asians had very strong gums. Dental care and procedures then, even in England, were much less advanced than today and I was quite ill for three days after the surgery. Mr. Boyce, very considerately, called every day to check on my progress.

A new society

On Saturday evenings many of us expatriates used to meet at specially-organized social events, which were attended by a large number of East European and Asian students. There were cocktails, dinner, and dancing which would go on till midnight. Some of the men present would confidently introduce themselves to the girls, but, initially, I was reluctant to do so for fear of being snubbed. However, once I shed my timidity I was able to find attractive dancing partners though the girls used to be quite selective, often refusing some of my friends’ requests. We would then introduce our partners to those who had been turned down.

Another regular meeting place for Ceylonese in London was the Ceylon Students’ Centre in Paddington. We went there regularly to enjoy what would have then been the cheapest meal in London, at 50 pence per head, which fetched us a tasty rice and curry. Quite naturally, the place used to be highly patronized, especially on weekends, when it was not unusual for the food to run out. There were also recreational activities, such as billiards, with the table being booked most of the time, and table tennis, at which I used to generally beat all comers.

I made many friends in London. Two people in particular, Siva and Pat Subramanium, who will feature later in this story, became very dear to me and my family.

Acquiring new tastes

The spell in London, my first overseas visit, inspired several significant changes in my vision and general outlook. On the one hand, it exposed me to the harsh realities of the international tea export trade. I learned lessons that I would never forget and, in many ways, which also helped me chart my business course over the next few decades. On the other, its long duration and the absence of severe work pressure gave me time for reflection, enabled me to absorb many new impressions and acquire new tastes, and also inculcated in me a life-long passion for travel and fresh cultural experiences.

Whilst never losing sight of both work and professional diligence as non-negotiable virtues, I also decided that life would be unfulfilled unless work was combined with fun, pleasure, and new experiences. I spent time and money on enjoying classical music, saving up to attend concerts at Albert Hall and Royal Festival Hall, as well as the opera and ballet at Covent Garden. I also enjoyed some amazing theatre in the West End. Those new cultural experiences fashioned my tastes, widening my horizons and enriching my world view. My subsequent travels all over the world, in the pursuit of my business, enabled me to indulge my tastes for such entertainment in many different countries.

While in London I purchased several classical music, opera, and ballet records and films from Harrods. The first day I bought some records, the sales assistant, Ms. Greenway, offered to hold my purchases until my departure, which was very convenient to me. She also helped me to select the best composers, quickly realizing that, despite my interest in classical music, my knowledge was poor.

When I returned to Ceylon after a five-month training, I brought with me Pds. 325. Mrs. Butler tried to persuade me to buy her terraced house for Pnds. 750, offering to arrange a mortgage. Rather shortsightedly, I did not even consider it. That apartment was worth four million pounds in the year 2019.

The purpose of my mission to London was to learn the art of branding and marketing of tea, the most vital segments of the tea industry, then almost totally dominated by Britain-based companies.

Even British companies operating in Ceylon were of the firm view that these vital aspects were beyond their competencies and reach and best left to the geniuses in London and other centres in the West.

Though my knowledge of plantations and the tea industry in general was limited, it was still of enormous value in understanding international marketing strategies and framing our tea farmers’ contribution in the context of the international tea trade, as demonstrated in London. What I saw and experienced during my training in London offered me a completely contrary view to my previous beliefs in the integrity of the British business style.