Midweek Review

George Keyt, Trinity College, and Phoebus Apollo

By Uditha Devapriya

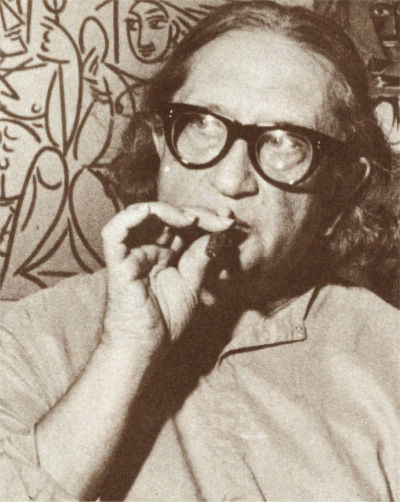

George Keyt, whose 30th death anniversary fell on 31 July, was easily Sri Lanka’s most distinctive, popular, and recognisable artist. In a career spanning 80 years he exhibited across Sri Lanka, India, Asia, and Europe. His fame eclipsed that of his colleagues in the 43 Group, barring perhaps Justin Däraniyagala, whose work remains more elusive. Indeed, the great John Berger, who thought highly of Däraniyagala, saw Keyt positively too.

Keyt’s work eludes easy categorisation and definition. To the last, he remained volatile and unpredictable, as much in his art as in his life. Perhaps it was that facet of his which his friend Martin Russell wanted to bring up when he began writing his obituary by mentioning his three marriages. Inspired by his personal life, his work continues to resonate within art circles and among critics and collectors. Among ordinary Sri Lankans, his paintings remain synonymous with modern art in this country. The one cannot be separated from the other. His evolution as an artist, then, remains linked to his evolution as a man.

Keyt’s intellectual formation began at Trinity College. Born to an Anglicised and Westernised Burgher middle-class, he remained a product of his time. Yet Trinity was by then undergoing a transformation under its principal, Reverend A. G. Fraser. Owing to Fraser, Keyt’s stint at Trinity coincided with a period of intense change. Caught in the midst of it all, he could not escape it. He was, of course, hardly studious: he frequently enraged his teachers for not being attentive enough in class. But Fraser would rescue him from punishment. Recognising his limitations and his talents, he would allow him to spend time at the library.

Briton Rivere, Phoebus Apollo

Yet while he owed his career and, in a sense, his later life to it, hardly nothing survives of Keyt’s career at Trinity College, of what he did and did not do there. The school Magazines, which date from the early 20th century, have pages and pages of articles and poems written by other distinguished past pupils, including Stanley Kirinde. By contrast, almost nothing of Keyt exists. This may be because, not being very studious, he did not bother participating in literary activities or societies. What is ironic about this is that he originally aspired to be a writer. It was later, at the behest of Lionel Wendt, that he changed course. And it was Fraser who, at Trinity, inculcated the love of reading in him.

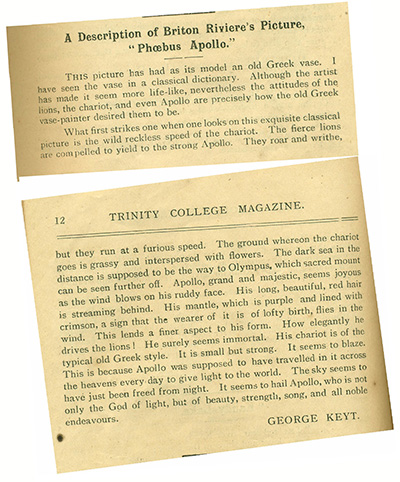

Given all this, the apparent absence of any writing by him is confounding. Yet there is one work of his which survives in these pages, an article from the 1917 edition of the College Magazine. Titled “A Description of Briton Riviere’s Picture, ‘Phoebus Apollo’”, it is a terse and succinct reflection on a late 19th century British painting depicting the eponymous Greek god charioteering among a pack of lions. Keyt delves into this painting and describes each aspect and element, how they contribute to the unity of the composition. At the time he would have been 15 or 16: a fact that makes the essay, compared with most other pieces in the Magazine, stand out as a well-rounded, highly intelligent critique.

A. G. Fraser

Keyt’s choice of subject probably had to do with what he was reading and absorbing in the College Library around this time. He could draw from an early age, and he immersed himself in religious stories, myths, poems. Fraser not only encouraged his love of reading, he also recommended what he should read. In 1916, a year before his essay on the Riviere work, Keyt exhibited his first painting at the Ceylon Society of Arts. The Society of Arts had been established to pander to colonial tastes. Led by the likes of A. C. G. S. Amarasekara and J. D. A. Perera, it championed academic art, or art modelled along the lines of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in France and the Royal Academy in England.

One of the most sought-after illustrators of his day, Briton Riviere (1840-1920) came from a family of academic artists. Like many of the painters and poets Keyt read up on at the time, Riviere was influenced by the Pre-Raphaelite Movement. While his work was much admired and was even featured in Punch, the leading British magazine of the day, he was derided for being “more engaged with the artistic quality of his work than the subject.” This comes out in his depiction of Phoebus Apollo. Keyt seems to have grasped if not discerned that aspect to his work rather well: “the attitudes of the lion, and even Apollo,” he notes, “are precisely how the old Greek vase-painter desired them to be.”

What is interesting about Keyt’s article is that it predicts his later critique of academic art, a genre the Pre-Raphael Movement opposed and sought to transcend. While Riviere’s family had thrown themselves into academic painting, Riviere also drew from a different tradition. Keyt would doubtless have been pulled to his painting in the same way he was pulled to the poetry of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. These artistes championed a return to a pristine past that had existed before the Industrial Age. They found a great champion of their cause in William Morris. Not surprisingly, as Keyt dug deeper, he discovered Morris as well.

These poets and painters idealised a world that lay beyond their reach. Their vision of that world influenced and inspired several intellectuals, notably Ananda Coomaraswamy, whose writings on Kandyan art are no different to William Morris’s championing of the Arts and Crafts Movement. Coomaraswamy’s writings, particularly in Mediaeval Sinhalese Art, left a deep impression on Keyt’s mind, pushing him to discover Buddhism through the Malwatte Vihare and later Hinduism through India. Riviere, in that sense, belonged to a tradition that resonated in Keyt’s mind. Yet among the many poems he read and the paintings he would have sampled at the Trinity College Library, it is this painting which appears to have pushed him to write about what he saw, barely a year before he left school.

- George Keyt (Courtesy Dhoonimal Gallery)

- Keyt’s article – Trinity College Magazine 1917, Volume I

Keyt’s fascination with gods and myths doubtless began at Trinity. Fraser’s interventions were pivotal in moulding him, nurturing him, encouraging him. Long after he left school he was allowed back into the Library. While not an active participant in school activities, he nevertheless opened his eyes to the changes that were unfolding in school. These included the Trinity College Chapel. A key highlight of the Chapel were the three great murals of David Paynter. Also influenced by the Pre-Raphael Movement, Paynter exercised a fascination with the human form: his murals in fact humanise the figure of Christ.

Keyt, on the other hand, preferred the larger-than-life, the otherworldly, the divine. It was this aspect to the Pre-Raphael Movement that got to him and made his later conversion to Buddhism and Hinduism easier. Indeed, it his admiration for Apollo which resonates in his essay: he hails him not just as the God of light, but also “of beauty, strength, song, and all noble endeavours.” Keyt is clearly in awe of the subject of the painting, his grandeur and his power, to which even the lions “are compelled to yield.” While he temporarily sought refuge in Buddhism, it was his discovery of Hinduism, with its vast pantheon of gods, that made him revisit and rediscover this love for the otherworldly.

Although it lay a world away from Riviere’s imagining of Apollo and the lions, the art of Kandy influenced Keyt as well. Trinity College lay at the centre of Kandy. Malwatte lay a few miles away, while the leading Raja Maha Viharayas of the region, prominently Degaldoruwa, stood farther away. The murals of these temples were different to the classical compositions of Riviere and Paynter. Yet they too were more preoccupied with idealised forms than actual representations. By no means realist or naturalist, they valorised gods, demons, and strange, majestic beasts, all revolving around the Buddha. Hailing from a middle-class family, young Keyt was fortunate in that his family allowed him to visit these places.

The 43 Group, of which Keyt remained a leading light, became purveyors of a tradition that had been lost to colonial middle-class tastes. In Tissa Liyanasuriya’s great documentary on the man, Keyt is described as revolutionary and reactionary: “revolutionary in his consistent struggle for artistic expression, reactionary in his deep homage to the creative vitality of the great and ancient Hindu and Buddhist tradition.” The seeds of this dualism were planted in Trinity, where he threw himself into the poetry and art of his time. He was not a student in the conventional sense, and he hardly bothered himself with studies. But as his essay shows, he did not waste his time at Trinity either. As the only written work of his to be published in a College magazine, the essay therefore underlies Keyt’s later evolution.

The writer wishes to thank the Trinity College Archives and the Curator of the Archives, Ms Thilini Dias Sumanasekera for granting access to the College Magazines.

This article is dedicated to Uthpala Wijesuriya, my assistant and associate, with whom I continue to peruse archives and explore historical sites across the country.

The writer is an international relations analyst, researcher, and columnist who can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com.

Midweek Review

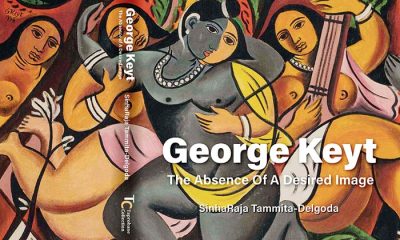

Aragalaya: GR blames CIA in Asanga Abeyagoonasekera’s explosive narrative

Did CIA chief William Burns visit Colombo in Feb 2023? Sri Lanka and the US refrained from formally confirming the visit. The Opposition sought confirmation of the then CIA Chief’s visit to Colombo in terms of the Right to Information Act but the Wickremesinghe-Rajapaksa government sidestepped the query. A former Republican congressman from Texas and Director of National Intelligence (2020–2021) John Ratcliffe succeeded Burns in late January 2025.

On the sheer weight of new evidence presented by Asanga Abeyagoonasekera’s ‘Winds of Change’, readers can get a clear picture of the forces that overthrew President Gotabaya Rajapaksa in 2022.

Even five years after the political upheaval, widely dubbed ‘Aragalaya,’ controversy surrounds the high-profile operation that forced wartime Defence Secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa to literally run for his dear life.

Gotabaya Rajapaksa, formerly of the Army but a novice to party politics, comfortably won the 2019 November presidential election against the backdrop of the Easter Sunday carnage that caused uncertainty and suspicions among communities. The economic crisis, also clandestinely engineered from abroad, firstly by crippling vital worker remittances from abroad, almost from the onset of Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s presidency, overwhelmed the government and created the environment conducive for external intervention. Could it have been avoided if the government, that enjoyed a near two-thirds majority in Parliament, sought the help of the International Monetary Fund (IMF)?

The costly and well-funded book project, undertaken at the time Abeyagoonasekera was working on a governance diagnostic report for the IMF, in the wake of the change of government in Sri Lanka, meticulously examined the former Lieutenant Colonel’s ouster, taking into consideration regional as well as global developments. Abeyagoonasekera dealt efficiently and furiously with rapidly changing situations and developments before the unprecedented 03 January, 2026, US raid on Venezuela.

Lt. Col. (retd) Gotabaya Rajapaksa, for some unexplainable reason and a considerable time after the events, has chosen to blame his ouster on the United States. We cannot blame him either, by the way we have seen how other regime changes had been engineered, in our region, by Washington, since and before Gotabaya’s ouster. The accusation is extraordinary as Gotabaya Rajapaksa in his memoirs ‘The conspiracy to oust me from presidency’ refrained from naming the primary conspirator, though he clearly alluded to an international conspiracy.

April 8, 2019 meeting

Launched in March 2024, in the run-up to the presidential election that brought Anura Kumara Dissanayake (AKD) to power, almost in a dream ride, if not for the intervening outside evil actors, ‘The conspiracy to oust me from presidency’ discussed the international conspiracy, but conveniently failed to name the primary conspirator. What made the former President speak so candidly with Abeyagoonasekera, the founding Director-General of the national security think tank, the Institute of National Security Studies Sri Lanka (INSS), under the Ministry of Defence, from 2016 to 2020?

Abeyagoonasekera also served as Executive Director at the Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute (LKI), under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2011–2015), during Mahinda Rajapaksa’s second term as the President. The author, both precisely and furiously, dealt with issues. Readers may find very interesting quotes and they do give a feeling of the author’s general hostility towards the US, India, as well as to the US-India marriage of convenience. Those who sense so may end up thinking ‘Change of Winds’ being supportive of the Chinese strategy. Among the highly sensitive quotes that underlined the Indian approach were attributed to Indian Defence Secretary Sanjay Mitra. The author quoted Mitra as having declared: “We need the MRCC centre [Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre], and you cannot give it to another nation.” As pointed out by the author, it was not a request but an order given to Sri Lanka on 8 April, 2019, meant to prevent Sri Lanka from even considering a competing proposal from China. Against that background, the author, who had been present at that meeting at which the Sri Lanka delegation was led by then Defence Secretary Hemasiri Fernando, questioned the failure on the part of the delegations to take up the Easter Sunday attacks. Terrorists struck two weeks later. Implications were telling.

That particular quote reveals the circumstances India and the US operated here. No wonder the incumbent government does not want to discuss the secret defence MoUs it has entered into with India and the US as they would clearly reveal the sellout of our interests.

The following line says a lot about the circumstances under which Gotabaya Rajapaksa was removed: “In Singapore, a senior journalist recounted how Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s resignation was scripted, under duress, at a hotel, facilitated by a foreign motorcade.”

In the first Chapter that incisively dealt with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the author was so lucky to secure an explosive quote from the ousted leader in an exclusive, hitherto unreported, interview in June 2024, a few months after the launch of Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s memoirs. The ex-President hadn’t minced his words when he alleged that the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) orchestrated his removal. He also claimed that he had been under US surveillance throughout his presidency.

The ousted leader has confidently cleared India’s Research and Analysis Wing (RAW) of complicity in the operation. What made him call Indian National Security Advisor (NSA) Ajit Doval ‘a good man,’ in response to Abeyagoonasekera’s pointed query. Abeyagoonasekera quoted Gotabaya Rajapaksa as having said: “… he would never do such things.” The ex-President must have some reason to call Doval a good friend, regardless of intense pressure exerted on him and the Mahinda Rajapaksa government by the Indians to do away with large scale Chinese-funded projects. (Doval in late October last year declared “poor governance” was the reason behind uprisings that led to change of governments in Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka over the period of past three-and-a-half years. The media quoted Doval as having said, during a function in New Delhi, that democracy and non-institutional methods of regime change in countries, such as Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Nepal, created their own set of problems. That was the first time a senior Indian government official made remarks on Nepal’s government change, followed by the Gen Z uprising in early September, 2025.)

Gotabaya Rajapaksa also cleared the Chinese of seeking to oust him. It would be pertinent to mention that China reacted sternly when at the onset of the Gotabaya presidency, the President suggested the need to re-negotiate the Hambantota Port deal.

During the treacherous ‘Yahapalana’ administration (2015 to 2019) Gotabaya Rajapaksa told me how Doval had pressed him to halt not only the Colombo Port City project but to take back Hambantota Port as well. By then, the Chinese had twisted the arms of the Yahapalana leaders Mairthpala Sirisena and Ranil Wickremesinghe and secured the Hambantota Port on a 99-year lease in a one-sided USD 1.2 bn deal. The Colombo Port City project, that had been halted by the Yahapalana government, too, was resumed possibly under Chinese threat or for some money incentive.

Once Wijeyadasa Rajapakshe, PC, declared, at a hastily arranged media briefing at Sri Lanka Foundation (SLF), that Sri Lanka would be relentlessly targeted as long as the Chinese held the Hambantota Port. The writer was present at that media briefing.

Wijeyadasa Rajapakshe said so in the aftermath of the 2019 Easter Sunday carnage, while disclosing his abortive bid to convince the Yahapalana government to abrogate the Hambantota Port deal. Did the parliamentarian know something we were not aware of? The author’s assessment, regarding the Easter Sunday attacks, based on interviews with Chinese officials and scholars, is frightening and an acknowledgement of a possible Western role in Sri Lanka’s destabilisation plot.

The ousted leader, in his lengthy interview with Abeyagoonasekera, made some attention-grabbing comments on the then US Ambassador here, Julie Chung. The ex-President questioned a particular aspect of Chung’s conduct during the protest campaign but his decision not to reveal it all in his memoirs is a mystery. Perhaps, one of the most thought-provoking queries raised by Abeyagoonasekera is the rationale in Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s claim that he didn’t want to suppress the protest campaign by using force against the backdrop of his own declaration that the CIA orchestrated the project.

Author’s foray into parliamentary politics

Gotabaya

For those genuinely interested in post-Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga developments, pertaining to international relations and geopolitics, may peruse ‘Winds of Change’ as the third of a trilogy. ‘Sri Lanka at Crossroads’ (2019) dealt with the Mahinda Rajapaksa period and ‘Conundrum of an Island’ (2021) discussed the treacherous Sirisena–Wickremesinghe alliance. The third in the series examined the end of the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna’s (SLPP) President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s rule and the rise of Anura Kumara Dissanayake (AKD) whom the author described as a Marxist, though this writer is of the view the JVP and NPP leader AKD is not so. AKD has clearly aligned his administration with US-India while trying to sustain existing relationship with China.

Among Asanga Abeyagoonasekera’s other books were ‘Towards a Better World Order’ (2015) and ‘Teardrop Diplomacy: China’s Sri Lanka Foray’ (2023, Bloomsbury).

Had Abeyagoonasekera succeeded in his bid to launch a political career in 2015, the trilogy on Sri Lanka may not have materialised. Abeyagoonasekera contested the Gampaha district at the August 2015 parliamentary election on the UNP ticket but failed to garner sufficient preferences to secure a place in Parliament. That dealt a devastating setback to Abeyagoonasekera’s political ambitions, but the Wickremesinghe-Sirisena administration created the Institute of National Security Studies Sri Lanka (INSS), under the Ministry of Defence, for him. Abeyagoonasekera received the appointment as the founding Director-General of the national security think tank, from 2016 to 2020.

Several persons dealt with ‘Aragalaya’ (the late Prof. Nalin de Silva used to call it (Paragalaya) before Abeyagoonasekera though none of them examined the regional and global contexts so deeply, taking into consideration the relevant developments. Having read Wimal Weerawansa’s (Nine: The hidden story), Sena Thoradeniya’s (Galle Face Protest; Systems Change or Anarchy?). Mahinda Siriwardena’s (Sri Lanka’s Economic Revival – Reflection on the Journey from Crisis to Recovery) and Prof. Sunanda Maddumabandara’s (Aragalaye Balaya), the writer is of the opinion Abeyagoonasekera dealt with the period in question as an incisive insider.

Abeyagoonasekera, as a person who left the country, under duress, in 2021, painted a frightening picture of a country with a small and vulnerable economy trapped in major global rivalries. The former government servant attributed his self–imposed exile to two issues.

The first was the 2019 Easter Sunday carnage. Why did the Wickremesinghe-Sirisena government ignore the warning issued by Abeyagoonasekera, in his capacity as DG INSS, in respect of the Easter Sunday bombing campaign? There is absolutely no ambiguity at all in his claim. Abeyagoonasekera insists that he alerted the government four months before the National Thowheed Jamath (NTJ) bombers struck. The bottom line is that Abeyagoonasekera had issued the warning several weeks before India did but those at the helm of that inept administration chose to turn a blind eye.

The second was the impending economic crisis that engulfed the country in 2022. Abeyagoonasekera is deeply bitter about his arrest on 21 July, 2024, at the Bandaranaike International Airport (BIA) over an alleged IRD –related offence as reported at that time, especially because he was returning home to visit his sick mother.

Asanga’s father Ossie, a member of Parliament and controversial figure, was killed in an LTTE suicide attack at Thotalanga in late Oct. 1994. The Chairman and leader of Sri Lanka Mahajana Pakshaya had been on stage with then UNP presidential election candidate Gamini Dissanayake when the woman suicide cadre blasted herself. The assassination was meant to ensure Kumaratunga’s victory. The LTTE probably felt that it could manipulate Kumaratunga than the experienced Dissanayake who may have had reached some sort of consensus with New Delhi on how to deal with the LTTE.

Let me reproduce a question posed to Asanga Abeyagoonasekera and his response in ‘Winds of Change’ as some may believe that the author is holding something back. “Didn’t they listen?” a US intelligence officer had asked me incredulously after the bombings. Years later, during my role as a technical advisor for the International Monetary Fund (IMF) amid Sri Lanka’s collapse, the question resurfaced: “How did you foresee the collapse of a powerful regime with a majority in parliament?” My answer remained the same—patterns. Rigorously gathered data and relentless analysis reveal the arcs of history before they unfold.

Perhaps, readers may find what former cashiered Flying Officer Keerthi Ratnayake had to say about ‘Aragalaya’ and related developments (https://island.lk/ex-slaf-officer-sheds-light-on-developments-leading-to-aragalaya/)

Bombshell claim

Essentially, Abeyagoonasekera, on the basis of his exclusive and lengthy interview with former President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, confirmed what Wimal Weerawansa and Sena Thoradeniya alleged that the US spearheaded the operation.

But Prof. Maddumabandara, a confidant of first post-Aragalaya President Ranil Wickremesinghe has bared the direct Indian involvement in the regime change operation. In spite of Gotabaya Rajapaksa confidently clearing Indian NSA Doval of complicity in his ouster, Prof. Maddumabandara is on record as having said that the then Indian High Commissioner here Gopal Baglay put pressure on Speaker Mahinda Yapa Abeywardena to take over the government for an interim period. (https://island.lk/dovals-questionable-regional-stock-taking/)

Obviously, the US and India worked together on the Sri Lanka regime change operation. That is the undeniable truth. India wanted to thwart Wickremesinghe receiving the presidency by bringing in Speaker Abeywardena. That move went awry in spite of some sections of both Buddhist and Catholic clergy throwing their weight behind New Delhi.

The 2022 violent regime change operation cannot be discussed without taking into consideration the US-led project that also involved the UNP, JVP and TNA to engineer retired General Sarath Fonseka’s victory at the 2010 presidential election and their backing for turncoat Maithripala Sirisena at the 2015 presidential election.

The section, titled ‘Echoes of Crisis from Sri Lanka to Bangladesh: South Asia’s Struggle in a Polycrisis’, is riveting and underscores the complexity of the situation and fragility of governments. Executive power and undisputable majorities in Parliament seems irrelevant as external powers intervene thereby making the electoral system redundant.

Having meticulously compared the overthrowing of Gotabaya Rajapaksa and Bangladesh’s Premier Sheikh Hasina, the author condemned them for their alleged failures and brutality. Abeyagoonasekera stated: “When the military sides with the protesters, as it did in Sri Lanka and now in Bangladesh, it reveals the rulers’ vulnerabilities.” The author unmercifully chided the former President for seeking refuge in the West while alleging direct CIA role in his ouster. But that may have spared his life. Had he sought a lifeline from the Chinese so late the situation could have taken a turn for worse.

The comment that had been attributed to Gotabaya Rajapaksa seemed to belittle Ranil Wickremesinghe who accepted the challenge of becoming the Premier in May 2022 and then chosen by the ruling SLPP to complete the remainder of Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s five-year term. Ranil was definitely seen as an opportunistic vulture who backed ‘Aragalaya’ without any qualms till he saw an opening for himself out of the chaos.

On Wickremesinghe’s path

Abeyagoonasekera discussed the joint US-Indian strategy pertaining to Sri Lanka. Whatever the National People’s Power (NPP) and its President say, the current dispensation is continuing Wickremesinghe’s policy as pointed out by the author. In fact, this government appears to be ready even to go beyond Wickremesinghe’s understanding with New Delhi. The Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on defence and the selling of the controlling interests of the Colombo Dockyard Limited (CDL) to India, mid last year, must have surprised even those who always pushed for enhanced relations at all levels.

The economic collapse that resulted in political upheaval has given New Delhi the perfect opportunity to consolidate its position here. Uncomplimentary comments on current Indian High Commissioner Santosh Jha in ‘Winds of Change’ have to be discussed, paying attention to Sri Lanka’s growing dependence and alleged clandestine activities of India’s Research and Analysis Wing (RAW). Abeyagoonasekera seemed to have no qualms in referring to RAW’s hand in 2019 Easter Sunday carnage.

Overall ‘Winds of Change’ encourages, inspires and confirms suspicions about US and Indian intelligence services and underscores the responsibility of those in power to be extra cautious. But, in the case of smaller and weaker economies, such as Sri Lanka still struggling to overcome the economic crisis, there seems to be no solution. Not only India and the US, the Chinese, too, pursue their agenda here unimpeded. Utilisation of political parties, represented in Parliament, selected individuals, and media, in the Chinese efforts, are obvious. Once parliamentarian Wijeyadasa Rajapakshe raised the Chinese interventions in Sri Lanka. He questioned the Parliament receiving about 240 personal laptops for all parliamentarians and top officials. The then UNPer told the writer his decision not to accept the laptop paid for by China. Perhaps, he is the only Sri Lankan politician to have written a strongly worded letter to Chinese leader Xi warning against high profile Chinese strategy.

Winds of Change

is available at

Vijitha Yapa and Sarasavi

By Shamindra Ferdinando

Midweek Review

Beginning of another ‘White Supremacist’ World Order?

Donald Trump’s complete lack of intelligence, empathy and common sense have become more apparent during the current term of his presidency. Ordinarily, a country’s wish to self-destruct as the United States seemingly does at present, and as the violence against US citizens and immigrants alike at the hands of federal authorities have shown in Minnesota, can be callously considered the business of that country. If the Trumpian imbecility was unfolding in Sri Lanka, anywhere else in South Asia or some other country of the purported Third World, the so-called World Order, led by the United States, would be preaching to us the values of democracy and human rights. But what happens when the actions of a powerful country, such as the United States, engulfs in the ensuing flames the rest of us? Trump and his madness then necessarily become our business, too, because combined with the military and economic power of the United States and its government’s proven lack of empathy for its own people, and the rest of the world, is quite literally a matter of global survival. Besides, one of the ‘positive’ outcomes of the Trumpian madness, as a friend observed recently, is that “he has single-handedly exposed and destroyed the fiction of ‘Western Civilisation’, including the pretenses of Europe.”

Donald Trump’s complete lack of intelligence, empathy and common sense have become more apparent during the current term of his presidency. Ordinarily, a country’s wish to self-destruct as the United States seemingly does at present, and as the violence against US citizens and immigrants alike at the hands of federal authorities have shown in Minnesota, can be callously considered the business of that country. If the Trumpian imbecility was unfolding in Sri Lanka, anywhere else in South Asia or some other country of the purported Third World, the so-called World Order, led by the United States, would be preaching to us the values of democracy and human rights. But what happens when the actions of a powerful country, such as the United States, engulfs in the ensuing flames the rest of us? Trump and his madness then necessarily become our business, too, because combined with the military and economic power of the United States and its government’s proven lack of empathy for its own people, and the rest of the world, is quite literally a matter of global survival. Besides, one of the ‘positive’ outcomes of the Trumpian madness, as a friend observed recently, is that “he has single-handedly exposed and destroyed the fiction of ‘Western Civilisation’, including the pretenses of Europe.”

It is in this context that the speech delivered by the Canadian Prime Minister, Mark Carney, at the World Economic Forum, in Davos, on 20 January, 2026, deserves attention. It was an elegant speech, a slap in the face of Trump and his policies, the articulation of the need for global directional change, all in one. But, pertinently, it was also a speech that did not clearly accept responsibility for the current world (dis)order which Carney says needs to change. The reality of that need, however, was overly reemphasised by Trump himself during his meandering, arrogant and incohesive speech delivered a day later, spanning over one hour.

My interest is in what Carney did not specifically say in his speech: who would constitute the new world order, who would be its leaders and why should we believe it would be any different from the present one?

Speaking in French, Carney observed that he was talking about “a rupture in the world order, the end of a pleasant fiction and the beginning of a harsh reality, where geopolitics, where the large, main power, geopolitics, is submitted to no limits, no constraints.” He was, of course, responding to the vulgar script for global domination put in place by the Trumpian United States, given Trump’s declared interest in seeing Canada as part of the United States, his avarice for Greenland, not to mention his already concluded grab for Venezuelan oil. But within this scenario, bound by ‘no limits’ and ‘no constraints’ he was also talking of Russia and China albeit in a coded language.

He reiterated, “that the other countries, especially intermediate powers like Canada, are not powerless. They have the capacity to build a new order that encompasses our values, such as respect for human rights, sustainable development, solidarity, sovereignty and territorial integrity of the various states. The power of the less power starts with honesty.”

Who could disagree with Carney? His words are a refreshing whiff of fresh air in the intellectual wasteland that is the Trumpian Oval Office and the current world order it prevails over. But where has been the ‘honesty’ of the less powerful in the specific situation where he equates Canada itself within this spectrum? He tells us that “the rules-based order is fading, that the strong can do what they can, and the weak must suffer what they must.”

That is stating the obvious. We have known this for decades by experience. Long before Canada’s relative silence with regard to Trump’s and US’ facilitation of the assault on Palestine and the massacre of its people, and the US President’s economic grab in Venezuela and the kidnapping of that country’s President and his wife, Canada’s own chorus in the world order that Carney now critiques has been embellished by silence or – even worse – by chords written by the global dominance orchestra of the United States.

He says the fading of the rules-based order has occurred because of the “strong tendency for countries to go along, to get along, to accommodate, to avoid trouble, to hope that compliance will buy safety.” Canada fits this description better than most other nations I can think of. But would Canada, along with other nations among the silent majority within the ‘intermediate powers’ take the responsibility for the mess in the world precisely that silence has directly led to creating? Who will pay for the pain many nations have endured in the prevailing world order? Will Canada lead the way in the new world order in doing this?

Carney further articulates that “for decades, countries like Canada prospered under what we called the rules-based international order. We joined its institutions, we praised its principles, we benefited from its predictability. And because of that, we could pursue values-based foreign policies under its protection.”

But this is not true, is it? Countries like Canada prospered not merely because of the stability of rules of the world order, but because they opted for silence when they should not have. The rupture and the chaos in the world order Carney now critiques and is insanely led by Trump today is not merely the latter’s creation. It has been co-authored for decades by countries such as Canada, France, the United Kingdom to mention just a few who also regularly chant the twin-mantras of human rights and democracy. Trump is merely the latest and the most vocal proponent of the nastiness of that World Order.

It is not that Carney is unaware of this unpleasant reality. He accepts that “the story of the international rules-based order was partially false, that the strongest would exempt themselves when convenient, that trade rules were enforced asymmetrically. And we knew that international law applied with varying rigour depending on the identity of the accused or the victim.”

While Canada seems to be coming to terms with this reality only now, countries like Sri Lanka and others in similarly disempowered positions in this world order have experienced this for decades, because, as I have outlined earlier, Canada et al have been complicit sustainers of the now demonised and demonic world order.

It is not that I disagree with the basic description Carney has painted of the status of the world. But from personal experience and from the perspective of a citizen from a powerless country, I simply do not trust those who preach ‘the gospel of the good’ not as a matter of principle, but only when the going gets tough for them.

At this rather late stage, Carney says, Canada is “amongst the first to hear the wake-up call, leading us to fundamentally shift our strategic posture.” Unfortunately, we, the people of countries who had to dance to the tunes of the world order led by the First World, have heard it for years, with no one listening to us when our discomforts were articulated. Now, Carney wants ‘middle powers’ or ‘intermediate powers’ within which he also locates Canada, “to live the truth?” For him, the truth means “naming reality” as it exists; “acting consistently” towards all in the world; “applying the same standards to allies and rivals” and “building what we claim to believe in, rather than waiting for the old order to be restored.” This appears to be the operational mantra for the new world order he is envisioning in which he sees Canada as a legitimate leader merely due to its late wakeup call.

He goes on to give a list of things Canada has done locally and globally and concludes by saying, “we have a recognition of what’s happening and a determination to act accordingly. We understand that this rupture calls for more than adaptation. It calls for honesty about the world as it is.” He goes on to say Canada also has “the capacity to stop pretending, to name reality, to build our strength at home and to act together.” He notes this is “Canada’s path. We choose it openly and confidently, and it is a path wide open to any country willing to take it with us.” Quite simply, this a leadership pitch for a new world order with Canada at its helm.

Without being overly cynical, this sounds very familiar, not too dissimilar to what USAID and Voice of America preached to the world; not too dissimilar to what the propaganda arms of the Soviet Union and the Chinese Communist Party used to preach in our own languages when we were growing up. It is difficult to buy this argument and accept Canadian and middle country leadership for the new world order when they have been consistently part of the problem of the old one and its excuses for institutionalised double standards practiced by international organisations such as the likes of the United Nations, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and other hegemonic entities that have catered to the whims of that world order.

As far as Canada is concerned, it is evident that it has suddenly woken up only due to an existential threat at home projected from across its southern border and Trump’s threats against the Danish territory of Greenland. When Gaza was battered, and Venezuela was raped, there was no audible clarion call. Therefore, there is no real desire for democracy or human rights in its true form, but a convenient and strategic interest in creating a new ‘white supremacist’ world order in the same persona as before, but this time led by a new white warrior instead. The rest of us would be mere followers, nodding our heads as expected as was the case before.

As the 20th century American standup comedian Lenny Bruce once said, “never trust a preacher with more than two suits.” Mr. Carney, Canada along with the so-called middle powers and the lapsed colonialists have way more than two suits, and we have seen them all.

Midweek Review

The MAD Spectre

Lo and behold the dangerous doings,

Of our most rational of animals,

Said to be the pride of the natural order,

Who stands on its head Perennial Wisdom,

Preached by the likes of Plato and Confucius,

Now vexing the earth and international waters,

With nuke-armed subs and other lethal weapons,

But giving fresh life to the Balance of Terror,

And the spectre of Mutually Assured Destruction.

By Lynn Ockersz

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoHayleys Mobility ushering in a new era of premium sustainable mobility

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoSLIM-Kantar People’s Awards 2026 to recognise Sri Lanka’s most trusted brands and personalities

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoAdvice Lab unveils new 13,000+ sqft office, marking major expansion in financial services BPO to Australia

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoArpico NextGen Mattress gains recognition for innovation

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoAltair issues over 100+ title deeds post ownership change

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoGovt. provoking TUs

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoSri Lanka opens first country pavilion at London exhibition

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoAll set for Global Synergy Awards 2026 at Waters Edge