Features

Flood Relief Should Help Victims, Not Bureaucracies

Sri Lanka has the capacity to respond to disaster. Donors should let it.

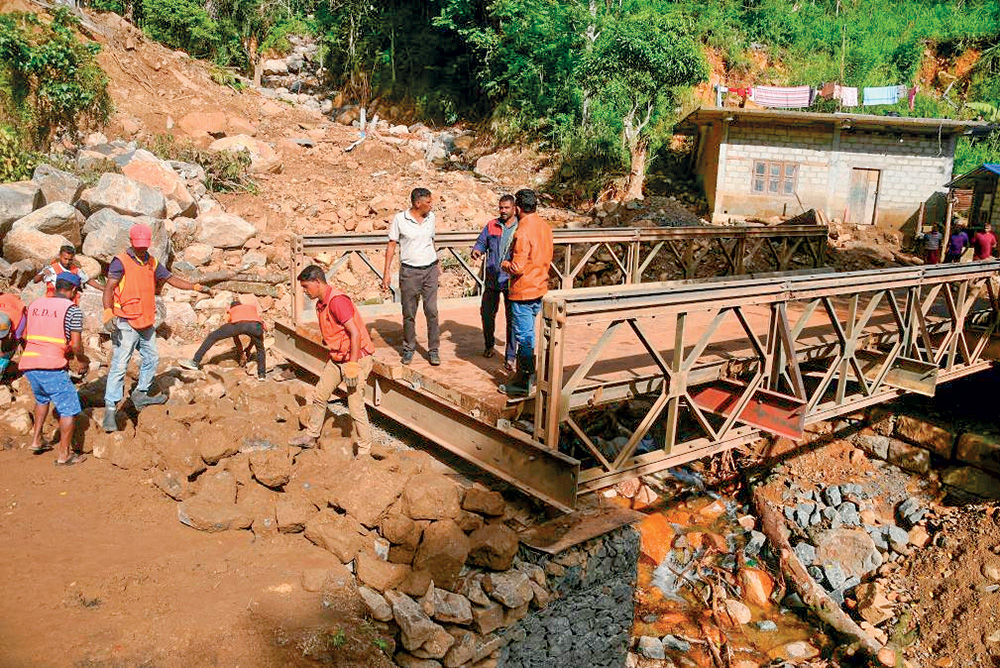

When floods swept through Sri Lanka in late November and early December, the need for swift assistance was undeniable. Lives were disrupted, livelihoods destroyed, and communities left exposed. In moments like these, speed matters. Judgment does too.

That is why the announcement on December 11 by Marc-André Franche, the United Nations resident coordinator in Sri Lanka, deserves closer attention. Mr. Franche said the U.N. was seeking to mobilize $35 million from donors, to be channeled through U.N. agencies for flood relief. About $9.5 million, he noted, had already been pledged, including by the European Union, Switzerland, Britain and the United States.

No one disputes that Sri Lanka needs help. The question is why the United Nations is setting up a parallel funding channel at all, when the Sri Lankan government has already activated its Disaster Management Fund, administered through national disaster authorities, and is actively seeking donor contributions for it.

U.N. appeals typically follow disasters when national institutions lack the capacity to deliver aid, when markets have collapsed, when donors distrust state systems, or when conflict makes neutrality essential. That logic held after the 2004 tsunami when large stretches of Sri Lanka’s coastline were under the control of the LTTE and again during the 2022 economic crisis when the government had reached an all-time low in terms of public distrust. It is much less obvious that any of those conditions apply today.

The United Nations, of course, has an argument of its own. Its agencies can move quickly in the first days of a crisis, drawing on pre-positioned stocks, standing contracts and surge staff. Many Western donors prefer routing funds through the U.N., pointing to fiduciary safeguards, standardized procurement rules and the political insulation that multilateral channels provide. In fragile or conflict-affected settings, neutrality can be indispensable.

In Sri Lanka’s current context, however, those arguments carry less weight. The government retains full territorial control. Markets are functioning. Public financial-management systems have undergone internationally validated reforms. Speed matters most in the first days of a disaster, precisely the window for which the U.N.’s global emergency fund, CERF, is designed. Beyond that initial phase, the rationale for diverting large sums into parallel bureaucratic systems weakens considerably. The prime minister announced this week that Sri Lanka has now moved into the next phase of recovery following the initial rescue and relief operations, making it all the more important that a parallel system not be entrenched. Coordination does not require financial control, and fiduciary risk alone cannot justify structural inefficiency where capable national systems already exist.

This debate is not confined to humanitarian aid. Earlier this year, Sri Lanka’s foreign minister rejected calls for expanded investigations by the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, arguing that externally driven accountability mechanisms risk undermining domestic processes and deepening political polarization. The government has maintained that questions of accountability and reconciliation should be addressed through Sri Lanka’s own legal and institutional frameworks. Whether one agrees or disagrees, the position reflects a consistent assertion by the state: parallel international mechanisms are not a substitute for functioning national systems. That logic applies as much to disaster response as it does to human rights oversight.

The government also maintains, credibly, that it has the administrative capacity, market access and logistical reach to manage emergency relief. After years of painful reform following the economic crisis, transparency in public finance has become a point of national pride. That assessment is not based on government assertion alone. In the wake of Sri Lanka’s economic crisis, both the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank have publicly acknowledged improvements in the country’s public financial management, transparency and fiscal oversight.

As part of the IMF-supported reform program, Sri Lanka has strengthened budget reporting, procurement controls and audit functions, while the World Bank has expanded technical assistance aimed at modernizing treasury systems, improving cash management and increasing the transparency of public expenditure. These reforms are incomplete and fragile, but they represent a material shift from the post-tsunami and post-economic crises period and are precisely the kinds of national systems donors say they want to support rather than bypass.

Moreover, there is no shortage of food or basic goods. What cannot be sourced locally can be procured quickly from neighboring countries. Logistically, too, U.N. agencies rely heavily on government departments, local NGOs and the private sector to deliver assistance. They no longer maintain the extensive field operations they once did during the civil war and the tsunami, which further weakens the argument that international organizations are best placed to manage large-scale delivery.

At its core, this debate is not really about the United Nations at all. It is about how donors and international organizations can best help countries like Sri Lanka recover from crises such as Ditwah. Notably, it is almost exclusively Western donors, as announced by the United Nations, that have chosen to channel assistance through this parallel mechanism, alongside a contribution announced by Japan a few days later. By contrast, countries from the Global South and other non-Western states — including India, China, Pakistan, Nepal, the Maldives, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Russia and Myanmar — have provided support largely through state-led mechanisms. The contrast is striking. It raises legitimate questions about why donor approaches diverge so sharply, and whether such differences risk blurring the lines between humanitarian assistance and broader geopolitical considerations, including perceptions of neutrality.

So why route scarce donor dollars through the U.N. and other large international organizations?

One explanation lies in the U.N.’s own financial distress. Its global budget is under unprecedented strain, weakened by chronic nonpayment from major contributors. In that environment, disasters also become opportunities to mobilize resources for the U.N. system itself, some of which eventually reach victims after passing through multiple institutional layers. Those layers come at a cost.

Donors, too, face incentives that discourage questioning the status quo. Aid ministries operate within rigid annual budget cycles and are under pressure to commit and disburse funds within a given fiscal year. Channeling money through large multilateral agencies offers a convenient solution: funds move quickly off national balance sheets, fiduciary responsibility is formally transferred, and donor governments can report internationally that they are supporting recognized humanitarian institutions. This dynamic helps explain why donor behavior often clusters around multilateral channels, particularly among Western governments operating within similar fiscal and political constraints, even when alternative models may offer greater value for money.

A major sector-wide analysis by Humanitarian Outcomes, linked to ALNAP, found that humanitarian financing dominated by large multilateral agencies is often slow and administratively heavy, particularly in the early days of a crisis. High transaction costs, including reporting requirements, compliance procedures and repeated donor processes, reduce the share of funds that reach people when they need them most.

Officially, U.N. agencies recover between seven and 13 percent of funds as “programme support costs,” money retained at headquarters for back-office functions. These funds never reach country offices. Beyond this, agencies charge the full cost of what they define as direct project expenses to donor-funded budgets. These include international and national staff salaries, consultants, vehicles, security, office rent, information technology, monitoring and evaluation, and donor-specific reporting.

Independent research by Development Initiatives and repeated observations by the U.N. Board of Auditors show that once these administrative and management costs are included, non-beneficiary expenditures can consume more than 40 percent of project budgets. In practical terms, a dollar routed through multilateral humanitarian channels may deliver less than fifty cents of tangible assistance on the ground.

(By contrast, providing direct cash assistance to victims of natural disasters typically costs less than five percent in administrative overhead and has been shown globally to be among the most effective and dignified forms of aid when local markets are functioning.)

Sri Lanka has seen this before.

After the 2004 tsunami, the U.N. system raised an unprecedented $120–140 million for Sri Lanka across agencies including UNICEF, the World Food Program, UNDP, UNHCR, WHO and FAO. Yet independent evaluations found that a year later, less than half of these funds had been disbursed — and “disbursed” often meant transferred to another intermediary rather than translated into houses, boats or livelihoods.

A senior U.N. official remarked at the time that “we have built many houses in our financial systems, but not a single one on the ground.”

In one telling episode, staff were encouraged to boost “delivery” figures by purchasing vehicles deemed necessary for field operations. Each U.N.-specification Land Cruiser cost roughly $40,000. At the government’s post-tsunami grant rate in 2005, that sum could have rebuilt more than 16 fully destroyed houses, housing roughly 80 people.

And it is not just a legacy of the tsunami years.

Recent experience offers a cautionary example. In June 2022, the United Nations launched a Humanitarian Needs and Priorities Plan for Sri Lanka, appealing for $149.7 million to assist 3.4 million vulnerable people across sectors including food, health and protection. The U.N.’s own Financial Tracking Service records that $182.4 million in humanitarian assistance flowed to Sri Lanka that year. Yet there is not a single publicly available document that consolidates how this money was actually spent, let alone one that distinguishes administrative and program costs from aid delivered on the ground.

The U.N.’s Sri Lanka Annual Results Reports for 2022 and 2023 avoid financial reporting altogether, focusing instead on broad, self-reported “results” that are difficult to verify. As of December 2025, the Annual Results Report for 2024 has still not been made public, an omission that would be unacceptable in most other institutional settings.

To be fair, the distrust that followed the tsunami and resurfaced during the 2022 economic crisis did not emerge in a vacuum. Weak governance, corruption scandals and the politicization of aid eroded donor confidence and justified heightened scrutiny at the time. But the lesson should not be that parallel systems are a permanent substitute for national ones. It should be that rebuilding trust requires transparency, independent oversight and accountability anchored in domestic institutions, not bypassing them indefinitely.

Sri Lanka’s experience is not unique. Evaluations from Indonesia after the Sulawesi earthquake, the Philippines after Typhoon Haiyan and India following the Kerala floods point to a similar conclusion: where capable state systems exist, parallel humanitarian financing often delays the transition from response to recovery rather than accelerating it.

The international humanitarian system, including U.N. agencies, also suffers from predictable incentive problems. Success is measured by money raised and money spent, not by recovery speed, resilience built or local capacity strengthened. Under annual appropriations and performance metrics focused on throughput, institutions optimize for what they are measured on. The result is a system that excels at mobilization and spending but struggles with efficiency and long-term impact.

There is one partial exception. The U.N. Central Emergency Response Fund, or CERF, is designed to provide rapid liquidity in the earliest days of a crisis. In early December, Sri Lanka received $4.5 million from CERF. Even here, transparency matters. Much of this funding replenishes pre-positioned stocks already drawn down, reimbursing existing expenditures rather than creating net new capacity. Public visibility into how those stocks are valued and how CERF disbursements align with national recovery plans remains limited.

None of this is an argument for excluding the U.N. altogether. Its technical expertise in water and sanitation, logistics, disease surveillance, and the protection of women and children can be invaluable. But that expertise is most effective when embedded within government systems, supporting ministries and local administrations, and focused on building durable national capacity rather than running parallel delivery structures.

Sri Lanka has learned hard lessons from past experiments. After the tsunami, $10 million in donor funds administered through UNDP were used to establish a Donor Assistance Database intended to track aid flows. It never delivered on its promise. Housed in an ad hoc agency that no longer exists, it disappeared along with the institution and the money.

A more constructive model is within reach. Donors could capitalize the Disaster Management Fund directly, subject to independent audits, real-time public dashboards and agreed performance benchmarks. The U.N. could provide embedded technical advisers and act as a third-party monitor, stepping in operationally only if clearly defined capacity thresholds fail.

Such a model would also clarify institutional roles. The Ministry of Finance would retain responsibility for budget execution, procurement and financial reporting. The Central Bank could support real-time monitoring of fund flows, liquidity management and payment systems, ensuring both speed and traceability. Parliamentary oversight, exercised through existing committees, would provide an additional layer of accountability, reviewing expenditures, audit findings and performance against agreed benchmarks. Together, these institutions offer a framework for transparency and control that donors routinely demand, without outsourcing financial authority to parallel external structures.

This is not to suggest that the government can or should act alone. Effective disaster response depends on a wide ecosystem that includes local NGOs, community-based organizations, the Sri Lankan private sector and international partners. Each brings capabilities the state does not always possess, from last-mile delivery and social trust to logistics, technology and specialized expertise. But direct intervention by international actors should be grounded in a clear, justifiable and verifiable comparative advantage, and accompanied by accountability mechanisms that are transparent, measurable and aligned with national systems. Absent that test, parallel intervention risks weakening, rather than strengthening, the very capacities disasters expose.

If the goal is genuine national ownership, stronger domestic institutions and cost-effective, sustainable results that reach those most affected, then the current model for delivering and accounting for aid deserves closer scrutiny. Rethinking that model is not optional; it is essential. The choice is not between national systems and international expertise. It is between financing delivery and financing bureaucracy.

The U.N. works in Sri Lanka at the government’s invitation. The country pays assessed contributions, provides prime land in Colombo rent-free, and covers utilities and services. That gives Sri Lankans not just the right, but the obligation, to ask hard questions.

If the U.N. secretary-general has pledged “all possible assistance,” as reported, the most constructive step now would be a simple one: support the Disaster Management Fund rather than compete with it.

As José Ramos-Horta, the Nobel Peace Prize–winning president of Timor-Leste, once observed of the vast U.N. administration that governed his country after independence, billions were spent “on Timor-Leste, but not in Timor-Leste.”

Sri Lanka, having learned once at great cost, should not have to learn that lesson again.

by a special correspondent

Features

Pakistan-Sri Lanka ‘eye diplomacy’

Reminiscences:

I was appointed Managing Director of the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation (CPC) and Chairman of the Trincomalee Petroleum Terminals Ltd (TPTL – Indian Oil Company/ Petroleum Corporation of Sri Lanka joint venture), in February 2023, by President Ranil Wickremesinghe. I served as TPTL Chairman voluntarily. TPTL controls the world-renowned oil tank farm in Trincomalee, abandoned after World War II. Several programmes were launched to repair tanks and buildings there. I enjoyed travelling to Trincomalee, staying at Navy House and monitoring the progress of the projects. Trincomalee is a beautiful place where I spent most of my time during my naval career.

My main task as MD, CPC, was to ensure an uninterrupted supply of petroleum products to the public.

With the great initiative of the then CPC Chairman, young and energetic Uvis Mohammed, and equally capable CPC staff, we were able to do our job diligently, and all problems related to petroleum products were overcome. My team and I were able to ensure that enough stocks were always available for any contingency.

The CPC made huge profits when we imported crude oil and processed it at our only refinery in Sapugaskanda, which could produce more than 50,000 barrels of refined fuel in one stream working day! (One barrel is equal to 210 litres). This huge facility encompassing about 65 acres has more than 1,200 employees and 65 storage tanks.

A huge loss the CPC was incurring due to wrong calculation of “out turn loss” when importing crude oil by ships and pumping it through Single Point Mooring Buoy (SPMB) at sea and transferring it through underwater fuel transfer lines to service tanks was detected and corrected immediately. That helped increase the CPC’s profits.

By August 2023, the CPC made a net profit of 74,000 million rupees (74 billion rupees)! The President was happy, the government was happy, the CPC Management was happy and the hard-working CPC staff were happy. I became a Managing Director of a very happy and successful State-Owned Enterprise (SOE). That was my first experience in working outside military/Foreign service.

I will be failing in my duty if I do not mention Sagala Rathnayake, then Chief of Staff to the President, for recommending me for the post of MD, CPC.

The only grievance they had was that we were not able to pay their 2023 Sinhala/Tamil New Year bonus due to a government circular. After working at CPC for six months and steering it out of trouble, I was ready to move out of CPC.

I was offered a new job as the Sri Lanka High Commissioner to Pakistan. I was delighted and my wife and son were happy. Our association with Pakistan, especially with the Pakistan Military, is very long. My son started schooling in Karachi in 1995, when I was doing the Naval War Course there. My wife Yamuna has many good friends in Pakistan. I am the first Military officer to graduate from the Karachi University in 1996 (BSc Honours in War Studies) and have a long association with the Pakistan Navy and their Special Forces. I was awarded the Nishan-e-Imtiaz (Military) medal—the highest National award by the Pakistan Presidentm in 2019m when I was Chief of Defence Staff. I am the only Sri Lankan to have been awarded this prestigious medal so far. I knew my son and myself would be able to play a quiet game of golf every morning at the picturesque Margalla Golf Club, owned by the Pakistan Navy, at the foot of Margalla hills, at Islamabad. The golf club is just a walking distance from the High Commissioner’s residence.

When I took over as Sri Lanka High Commissioner at Islamabad on 06 December 2023, I realised that a number of former Service Commanders had held that position earlier. The first Ceylonese High Commissioner to Pakistan, with a military background, was the first Army Commander General Anton Muthukumaru. He was concurrently Ambassador to Iran. Then distinguished Service Commanders, like General H W G Wijayakoon, General Gerry Silva, General Srilal Weerasooriya, Air Chief Marshal Jayalath Weerakkody, served as High Commissioners to Islamabad. I took over from Vice Admiral Mohan Wijewickrama (former Chief of Staff of Navy and Governor Eastern Province).

A photograph of Dr. Silva (second from right) in Brigadier

(Dr) Waquar Muzaffar’s album

One of the first visitors I received was Kawaja Hamza, a prominent Defence Correspondent in Islamabad. His request had nothing to do with Defence matters. He wanted to bring his 84-year-old father to see me; his father had his eyesight restored with corneas donated by a Sri Lankan in 1972! His eyesight is still good, but he did not know the Sri Lankan donor who gave him this most precious gift. He wanted to pay gratitude to the new Sri Lankan High Commissioner and to tell him that as a devoted Muslim, he prayed for the unknown donor every day! That reminded me of what my guru in Foreign Service, the late Foreign Minister Lakshman Kadirgamar told me when I was First Secretary/ Defence Advisor, Sri Lanka High Commission in New Delhi. That is “best diplomacy is people-to-people contacts.” This incident prompted me to research more into “Pakistan-Sri Lanka Eye Diplomacy” and what I learnt was fascinating!

Do you know the Sri Lanka Eye Donation Society has donated more than 26,000 corneas to Pakistan, since 1964 to date! That means more than 26,000 Pakistani people see the world with SRI LANKAN EYES! The Sri Lankan Eye Donation Society has provided 100,000 eye corneas to foreign countries FREE! To be exact 101,483 eye corneas during the last 65 years! More than one fourth of these donations was to one single country- Pakistan. Recent donations (in November 2024) were made to the Pakistan Military at Armed Forces Institute of Ophthalmology (AFIO), Rawalpindi, to restore the sight of Pakistan Army personnel who suffered eye injuries due to Improvised Explosive Devices (IED) blasts. This donation was done on the 75th Anniversary of the Sri Lanka Army.

Deshabandu Dr. F. G. Hudson Silva, a distinguished old boy of Nalanda College, Colombo, started collecting eye corneas as a medical student in 1958. His first set of corneas were collected from a deceased person and were stored at his home refrigerator at Wijerama Mawatha, Colombo 7. With his wife Iranganie De Silva (nee Kularatne), he started the Sri Lanka Eye Donation Society in 1961. They persuaded Buddhists to donate their eyes upon death. This drive was hugely successful.

Their son (now in the US) was a contemporary of mine at Royal College. I pledged to donate (of course with my parents’ permission) my eyes upon my death when I was a student at Royal college in 1972 on a Poson Full Moon Poya Day. Thousands have done so.

On Vesak Full Moon Poya Day in 1964, the first eye corneas were carried in a thermos flask filled with Ice, to Singapore, by Dr Hudson Silva and his wife and a successful eye transplant surgery was performed. From that day, our eye corneas were sent to 62 different countries.

Pakistan Lions Clubs, which supported this noble gesture, built a beautiful Eye Hospital for humble people at Gulberg, Lahore, where eye surgeries are performed, and named it Dr Hudson Silva Lions Eye Hospital.

The good work has continued even after the demise of Dr Hudson Silva in 1999.

So many people have donated their eyes upon their death, including President J. R. Jayewardene, whose eye corneas were used to restore the eyesight of one Japanese and one Sri Lankan. Dr Hudson Silva became a great hero in Pakistan and he was treated with dignity and respect whenever he visited Pakistan. My friend, Brigadier (Dr) Waquar Muzaffar, the Commandant of AFIO, was able to dig into his old photographs and send me a precious photo taken in 1980, 46 years ago (when he was a medical student), with Dr Hudson Silva.

We will remember Dr and Mrs Hudson Silva with gratitude.

Bravo Zulu to Sri Lanka Eye Donation Society!

by Admiral Ravindra C Wijegunaratne

by Admiral Ravindra C Wijegunaratne

WV, RWP and Bar, RSP, VSV, USP, NI (M) (Pakistan), ndc, psn, Bsc

(Hons) (War Studies) (Karachi) MPhil (Madras)

Former Navy Commander and Former Chief of Defense Staff

Former Chairman, Trincomalee Petroleum Terminals Ltd

Former Managing Director Ceylon Petroleum Corporation

Former High Commissioner to Pakistan

Features

Lasting solutions require consensus

Problems and solutions in plural societies like Sri Lanka’s which have deep rooted ethnic, religious and linguistic cleavages require a consciously inclusive approach. A major challenge for any government in Sri Lanka is to correctly identify the problems faced by different groups with strong identities and find solutions to them. The durability of democratic systems in divided societies depends less on electoral victories than on institutionalised inclusion, consultation, and negotiated compromise. When problems are defined only through the lens of a single political formation, even one that enjoys a large electoral mandate, such as obtained by the NPP government, the policy prescriptions derived from that diagnosis will likely overlook the experiences of communities that may remain outside the ruling party. The result could end up being resistance to those policies, uneven implementation and eventual political backlash.

A recent survey done by the National Peace Council (NPC), in Jaffna, in the North, at a focus group discussion for young people on citizen perception in the electoral process, revealed interesting developments. The results of the NPC micro survey support the findings of the national survey by Verite Research that found that government approval rating stood at 65 percent in early February 2026. A majority of the respondents in Jaffna affirm that they feel safer and more fairly treated than in the past. There is a clear improving trend to be seen in some areas, but not in all. This survey of predominantly young and educated respondents shows 78 percent saying livelihood has improved and an equal percentage feeling safe in daily life. 75 percent express satisfaction with the new government and 64 percent believe the state treats their language and culture fairly. These are not insignificant gains in a region that bore the brunt of three decades of war.

Yet the same survey reveals deep reservations that temper this optimism. Only 25 percent are satisfied with the handling of past issues. An equal percentage see no change in land and military related concerns. Most strikingly, almost 90 percent are worried about land being taken without consent for religious purposes. A significant number are uncertain whether the future will be better. These negative sentiments cannot be brushed aside as marginal. They point to unresolved structural questions relating to land rights, demilitarisation, accountability and the locus of political power. If these issues are not addressed sooner rather than later, the current stability may prove fragile. This suggests the need to build consensus with other parties to ensure long-term stability and legitimacy, and the need for partnership to address national issues.

NPP Absence

National or local level problems solving is unlikely to be successful in the longer term if it only proceeds from the thinking of one group of people even if they are the most enlightened. Problem solving requires the engagement of those from different ethno-religious, caste and political backgrounds to get a diversity of ideas and possible solutions. It does not mean getting corrupted or having to give up the good for the worse. It means testing ideas in the public sphere. Legitimacy flows not merely from winning elections but from the quality of public reasoning that precedes decision-making. The experience of successful post-conflict societies shows that long term peace and development are built through dialogue platforms where civil society organisations, political actors, business communities, and local representatives jointly define problems before negotiating policy responses.

As a civil society organisation, the National Peace Council engages in a variety of public activities that focus on awareness and relationship building across communities. Participants in those activities include community leaders, religious clergy, local level government officials and grassroots political party representatives. However, along with other civil society organisations, NPC has been finding it difficult to get the participation of members of the NPP at those events. The excuse given for the absence of ruling party members is that they are too busy as they are involved in a plenitude of activities. The question is whether the ruling party members have too much on their plate or whether it is due to a reluctance to work with others.

The general belief is that those from the ruling party need to get special permission from the party hierarchy for activities organised by groups not under their control. The reluctance of the ruling party to permit its members to join the activities of other organisations may be the concern that they will get ideas that are different from those held by the party leadership. The concern may be that these different ideas will either corrupt the ruling party members or cause dissent within the ranks of the ruling party. But lasting reform in a plural society requires precisely this exposure. If 90 percent of surveyed youth in Jaffna are worried about land issues, then engaging them, rather than shielding party representatives from uncomfortable conversations, is essential for accurate problem identification.

North Star

The Leader of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP), Prof Tissa Vitarana, who passed away last week, gave the example for national level problem solving. As a government minister he took on the challenge the protracted ethnic conflict that led to three decades of war. He set his mind on the solution and engaged with all but never veered from his conviction about what the solution would be. This was the North Star to him, said his son to me at his funeral, the direction to which the Compass (Malimawa) pointed at all times. Prof Vitarana held the view that in a diverse and plural society there was a need to devolve power and share power in a structured way between the majority community and minority communities. His example illustrates that engagement does not require ideological capitulation. It requires clarity of purpose combined with openness to dialogue.

The ethnic and religious peace that prevails today owes much to the efforts of people like Prof Vitarana and other like-minded persons and groups which, for many years, engaged as underdogs with those who were more powerful. The commitment to equality of citizenship, non-racism, non-extremism and non-discrimination, upheld by the present government, comes from this foundation. But the NPC survey suggests that symbolic recognition and improved daily safety are not enough. Respondents prioritise personal safety, truth regarding missing persons, return of land, language use and reduction of military involvement. They are also asking for jobs after graduation, local economic opportunity, protection of property rights, and tangible improvements that allow them to remain in Jaffna rather than migrate.

If solutions are to be lasting they cannot be unilaterally imposed by one party on the others. Lasting solutions cannot be unilateral solutions. They must emerge from a shared diagnosis of the country’s deepest problems and from a willingness to address the negative sentiments that persist beneath the surface of cautious optimism. Only then can progress be secured against reversal and anchored in the consent of the wider polity. Engaging with the opposition can help mitigate the hyper-confrontational and divisive political culture of the past. This means that the ruling party needs to consider not only how to protect its existing members by cloistering them from those who think differently but also expand its vision and membership by convincing others to join them in problem solving at multiple levels. This requires engagement and not avoidance or withdrawal.

by Jehan Perera

Features

Unpacking public responses to educational reforms

As the debate on educational reforms rages, I find it useful to pay as much attention to the reactions they have excited as we do to the content of the reforms. Such reactions are a reflection of how education is understood in our society, and this understanding – along with the priorities it gives rise to – must necessarily be taken into account in education policy, including and especially reform. My aim in this piece, however, is to couple this public engagement with critical reflection on the historical-structural realities that structure our possibilities in the global market, and briefly discuss the role of academics in this endeavour.

As the debate on educational reforms rages, I find it useful to pay as much attention to the reactions they have excited as we do to the content of the reforms. Such reactions are a reflection of how education is understood in our society, and this understanding – along with the priorities it gives rise to – must necessarily be taken into account in education policy, including and especially reform. My aim in this piece, however, is to couple this public engagement with critical reflection on the historical-structural realities that structure our possibilities in the global market, and briefly discuss the role of academics in this endeavour.

Two broad reactions

The reactions to the proposed reforms can be broadly categorised into ‘pro’ and ‘anti’. I will discuss the latter first. Most of the backlash against the reforms seems to be directed at the issue of a gay dating site, accidentally being linked to the Grade 6 English module. While the importance of rigour cannot be overstated in such a process, the sheer volume of the energies concentrated on this is also indicative of how hopelessly homophobic our society is, especially its educators, including those in trade unions. These dispositions are a crucial part of the reason why educational reforms are needed in the first place. If only there was a fraction of the interest in ‘keeping up with the rest of the world’ in terms of IT, skills, and so on, in this area as well!

Then there is the opposition mounted by teachers’ trade unions and others about the process of the reforms not being very democratic, which I (and many others in higher education, as evidenced by a recent statement, available at https://island.lk/general-educational-reforms-to-what-purpose-a-statement-by-state-university-teachers/ ) fully agree with. But I earnestly hope the conversation is not usurped by those wanting to promote heteronormativity, further entrenching bigotry only education itself can save us from. With this important qualification, I, too, believe the government should open up the reform process to the public, rather than just ‘informing’ them of it.

It is unclear both as to why the process had to be behind closed doors, as well as why the government seems to be in a hurry to push the reforms through. Considering other recent developments, like the continued extension of emergency rule, tabling of the Protection of the State from Terrorism Act (PSTA), and proposing a new Authority for the protection of the Central Highlands (as is famously known, Authorities directly come under the Executive, and, therefore, further strengthen the Presidency; a reasonable question would be as to why the existing apparatus cannot be strengthened for this purpose), this appears especially suspect.

Further, according to the Secretary to the MOE Nalaka Kaluwewa: “The full framework for the [education] reforms was already in place [when the Dissanayake government took office]” (https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2025/08/12/wxua-a12.html, citing The Morning, July 29). Given the ideological inclinations of the former Wickremesinghe government and the IMF negotiations taking place at the time, the continuation of education reforms, initiated in such a context with very little modification, leaves little doubt as to their intent: to facilitate the churning out of cheap labour for the global market (with very little cushioning from external shocks and reproducing global inequalities), while raising enough revenue in the process to service debt.

This process privileges STEM subjects, which are “considered to contribute to higher levels of ‘employability’ among their graduates … With their emphasis on transferable skills and demonstrable competency levels, STEM subjects provide tools that are well suited for the abstraction of labour required by capitalism, particularly at the global level where comparability across a wide array of labour markets matters more than ever before” (my own previous piece in this column on 29 October 2024). Humanities and Social Sciences (HSS) subjects are deprioritised as a result. However, the wisdom of an education policy that is solely focused on responding to the global market has been questioned in this column and elsewhere, both because the global market has no reason to prioritise our needs as well as because such an orientation comes at the cost of a strategy for improving the conditions within Sri Lanka, in all sectors. This is why we need a more emancipatory vision for education geared towards building a fairer society domestically where the fruits of prosperity are enjoyed by all.

The second broad reaction to the reforms is to earnestly embrace them. The reasons behind this need to be taken seriously, although it echoes the mantra of the global market. According to one parent participating in a protest against the halting of the reform process: “The world is moving forward with new inventions and technology, but here in Sri Lanka, our children are still burdened with outdated methods. Opposition politicians send their children to international schools or abroad, while ours depend on free education. Stopping these reforms is the lowest act I’ve seen as a mother” (https://www.newsfirst.lk/2026/01/17/pro-educational-reforms-protests-spread-across-sri-lanka). While it is worth mentioning that it is not only the opposition, nor in fact only politicians, who send their children to international schools and abroad, the point holds. Updating the curriculum to reflect the changing needs of a society will invariably strengthen the case for free education. However, as mentioned before, if not combined with a vision for harnessing education’s emancipatory potential for the country, such a move would simply translate into one of integrating Sri Lanka to the world market to produce cheap labour for the colonial and neocolonial masters.

According to another parent in a similar protest: “Our children were excited about lighter schoolbags and a better future. Now they are left in despair” (https://www.newsfirst.lk/2026/01/17/pro-educational-reforms-protests-spread-across-sri-lanka). Again, a valid concern, but one that seems to be completely buying into the rhetoric of the government. As many pieces in this column have already shown, even though the structure of assessments will shift from exam-heavy to more interim forms of assessment (which is very welcome), the number of modules/subjects will actually increase, pushing a greater, not lesser, workload on students.

A file photo of a satyagraha against education reforms

What kind of education?

The ‘pro’ reactions outlined above stem from valid concerns, and, therefore, need to be taken seriously. Relatedly, we have to keep in mind that opening the process up to public engagement will not necessarily result in some of the outcomes, those particularly in the HSS academic community, would like to see, such as increasing the HSS component in the syllabus, changing weightages assigned to such subjects, reintroducing them to the basket of mandatory subjects, etc., because of the increasing traction of STEM subjects as a surer way to lock in a good future income.

Academics do have a role to play here, though: 1) actively engage with various groups of people to understand their rationales behind supporting or opposing the reforms; 2) reflect on how such preferences are constituted, and what they in turn contribute towards constituting (including the global and local patterns of accumulation and structures of oppression they perpetuate); 3) bring these reflections back into further conversations, enabling a mutually conditioning exchange; 4) collectively work out a plan for reforming education based on the above, preferably in an arrangement that directly informs policy. A reform process informed by such a dialectical exchange, and a system of education based on the results of these reflections, will have greater substantive value while also responding to the changing times.

Two important prerequisites for this kind of endeavour to succeed are that first, academics participate, irrespective of whether they publicly endorsed this government or not, and second, that the government responds with humility and accountability, without denial and shifting the blame on to individuals. While we cannot help the second, we can start with the first.

Conclusion

For a government that came into power riding the wave of ‘system change’, it is perhaps more important than for any other government that these reforms are done for the right reasons, not to mention following the right methods (of consultation and deliberation). For instance, developing soft skills or incorporating vocational education to the curriculum could be done either in a way that reproduces Sri Lanka’s marginality in the global economic order (which is ‘system preservation’), or lays the groundwork to develop a workforce first and foremost for the country, limited as this approach may be. An inextricable concern is what is denoted by ‘the country’ here: a few affluent groups, a majority ethno-religious category, or everyone living here? How we define ‘the country’ will centrally influence how education policy (among others) will be formulated, just as much as the quality of education influences how we – students, teachers, parents, policymakers, bureaucrats, ‘experts’ – think about such categories. That is precisely why more thought should go to education policymaking than perhaps any other sector.

(Hasini Lecamwasam is attached to the Department of Political Science, University of Peradeniya).

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.

-

Life style4 days ago

Life style4 days agoMarriot new GM Suranga

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoMinistry of Brands to launch Sri Lanka’s first off-price retail destination

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoMonks’ march, in America and Sri Lanka

-

Opinion7 days ago

Opinion7 days agoWill computers ever be intelligent?

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoThe Rise of Takaichi

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoWetlands of Sri Lanka:

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoThailand to recruit 10,000 Lankans under new labour pact

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoMassive Sangha confab to address alleged injustices against monks