Opinion

Five Years on with garbage, myths and lies

Sri Lanka – Singapore Free Trade Agreement

By Gomi Senadhira

This month the highly controversial Sri Lanka – Singapore Free Trade Agreement (SLSFTA), which was signed in January 2018 and enforced in May 2018, completes five years in operation. Given the high level of concern among domestic stakeholders regarding the agreement. President Maithripala Sirisena appointed an independent committee of experts, in August 2018, to study the agreement and the committee handed over its report to the President in December 2018. The committee had identified a number of pitfalls in the agreement and President Maithripala Sirisena had directed that the agreement be amended as per the recommendations of the expert group. In May 2021, it was revealed that the National Negotiation Committee had reviewed the SLSFTA and identified 18 amendments to be made to the agreement. Hence, as the SLSFTA marks five years of implementation, it is appropriate for relevant government agencies to provide an overview of the significant trade and economic effects of the FTA during the period, and any efforts undertaken by the government to revise the articles in the agreement which are unfavourable to Sri Lanka. This is particularly important in trade policy because Sri Lanka is currently engaged in FTA negotiations with a number of other countries, including China, India, and Thailand. A careful analysis of the SLSFTA, at this stage, would help to avoid repeating similar mistakes in these negotiations as well. Furthermore, the way our trade negotiators and “experts” reacted to some of these public concerns on the agreement also reveals the limits of their expertise on trade agreements and negotiations, and their understanding of the commitments they had extended to Singapore! Some of their comments are so absurd that it appears that they do not even comprehend the very basics of trade negotiations!

One of the most controversial issues in the SLSFTA was the commitments undertaken by Sri Lanka to open up import and process waste/garbage from Singapore. I was the first to raise this issue in August 2018 (SL chosen as garbage dump by Singapore after China, etc. shut their doors, The Island 18th August 2018). Last year, in a study undertaken by Anushka Wijesinha, who was an advisor to the Ministry of Development Strategies and International Trade, and Janaka Wijayasiri state, “At times, the concern morphed into undue fears and propelled misleading views and myths…Another concern that arose quite surprisingly was that the SLFTA – and the tariff liberalisation offered – would permit harmful products such as garbage, clinical waste, nuclear waste, chemical waste etc. to be imported to Sri Lanka. The argument by those individuals and groups that raised this issue was that since waste products are included in the TLP, such items can be dumped into the country under the agreement… To be clear, the reduction or elimination of tariffs does not grant automatic entry of a product into a country – all applicable domestic regulations and mechanisms would still apply, including any applicable import licensing requirements, standards, and other regulatory approvals. The SLSFTA does not take away Sri Lanka’s rights under International Environmental Protection Treaties to which Sri Lanka is a signatory and therefore, relevant environmental laws and regulations would apply to such imported products with no exception for those imports from Singapore under the SLSFTA.” (Sri Lanka – Singapore FTA Four Years On: Policy Context, Key Issues, and Future Prospects – August 2022)

When I exposed the commitments undertaken in the agreement to allow waste, particularly plastic waste, imports from Singapore it was not done based simply on tariff liberalisation. It was done after analysing the global trade of plastic waste, the challenges Singapore was facing in exporting plastic waste, Sri Lanka’s import of plastic waste, and Sri Lanka’s commitments in the agreement under the TLP, rules of origin, and services.

The Global situation

The developed countries lawfully or unlawfully export garbage as “recyclable waste” overseas for recycling. That is because recycling is a labour-intensive and dirty industry. For example, a PET bottle would have to be washed, its cap, and the label taken off before it can be recycled. So, it is a labour- intensive process. Very often large quantities of toxic or hazardous wastes also are mixed with “clean” waste. Then it also becomes a hazardous industry. During the cleaning process toxic waste is released into local environs and workers get exposed to them. So, developed countries prefer to do this “recycling” in developing countries. To do their dirty work these global garbage traders particularly target developing countries with corrupt officials and shady businessmen where import licensing requirements, standards, and other regulatory approvals can be bent and corrupt officials would facilitate the clearing of even toxic garbage containers without any examination. In these countries, the bulk of the imported garbage ends up in the local garbage dumps.

China was the world’s largest importer of garbage and imported almost 60% of the world’s plastic waste. However, there was a growing public outcry, over many years, against the import of “foreign garbage.” in general and import of plastic waste in particular. This intensified after the release of the documentary film “Plastic China” in 2016 depicting the lives of two families who make their living recycling plastic waste imported from developed countries. In 2017 China decided to ban imports of 24 types of rubbish and notified the WTO accordingly. “We found that large amounts of dirty wastes or even hazardous wastes are mixed in the solid waste that can be used as raw materials. This seriously polluted China’s environment. To protect China’s environmental interests and people’s health, we urgently adjust the imported solid wastes list, and forbid the import of solid wastes that are highly polluted. Protection of human health or safety; Protection of animal or plant life or health; Protection of the environment,” stated China’s WTO notification.

Normally, in international trade when the import of a product is banned in one country, it will be redirected to other countries. After the Chinese ban. Increased volumes of plastic waste started to move into other traditional importers of waste for reprocessing (Thailand, Vietnam, and other countries in the region) and these countries too started to restrict the imports of waste products. So, where will the world’s waste exports end up, if not in China or South East Asia? By late 2016, the Chinese plastic waste processing industry was looking for places in South Asia and Africa to relocate this billion-dollar industry.

Situation in Singapore

Situation in Singapore

Singapore is one of the world’s largest, per capita, plastic waste generators. From 2012 to 2017 the total volume of plastic waste generated in Singapore averaged around 800 thousand tons per year. In 2013 Singapore exported over 90,000 tons of plastic waste. Out of it over 57,000 Tons went to China. After China’s ban on the import of plastic waste, Singapore’s exports fell to around 30, 000 tons by 2021. In Singapore, plastic waste is either exported or incinerated. Ash from incineration is shipped to a man-made island and that landfill is also fast filling up. Furthermore, the incineration of plastic waste even under controlled conditions leads to environmental degradation. Singapore is very keen on maintaining its air quality and incineration is not a preferred option. But recycling in Singapore is expensive. So, recycling companies in Singapore used to undertake that in Malaysia, China, or other countries in the region. After the Chinese ban exports to China have stopped totally and other importers also were contemplating import restrictions. Hence, it was no secret, when the SLSFTA was negotiated Singapore was exploring new overseas locations to establish recycling operations, or dumping grounds. In 2021 Singapore generated 982 thousand tons of plastic waste and only around six percent of the plastic waste generated was recycled. (See Table I)

The situation in Sri Lanka

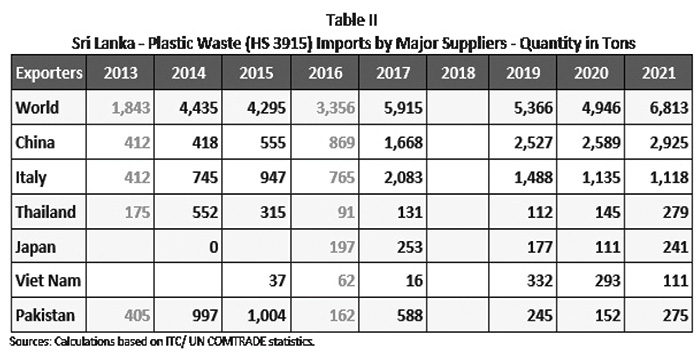

When the SLSFTA was under negotiation Sri Lanka had already commenced importing plastic waste. The surge in imports between 2013 and 2017 shown in the Table II, clearly indicated the presence of a small but growing plastic waste “recycling” industry in Sri Lanka. My comments in 2018 was partly based on this analysis. (See Table II)

When the SLSFTA was under negotiation Sri Lanka had already commenced importing plastic waste. The surge in imports between 2013 and 2017 shown in the Table II, clearly indicated the presence of a small but growing plastic waste “recycling” industry in Sri Lanka. My comments in 2018 was partly based on this analysis. (See Table II)

Though trade flows indicated a possible presence of global waste “recycling” mafia in Sri Lanka, I didn’t know, at that stage, garbage “recycling” or “resource recovery industries” had already commenced thriving operations within the BOI, under the Commercial Hub Regulation Act.

That was revealed only after the media exposure in 2019, of a huge waste dump inside the BOI. At that time, a representative from the “resource recovery industry” operated in the Katunayake FTZ, brazenly claimed at a press conference that this was the world’s “fastest-growing and most admired industry”. However, the investigation revealed that this clandestine waste dump inside the BOI contained toxic waste. Then came the discovery of over 200 stinking garbage containers in the Colombo port! Again, with toxic waste! These were discovered only because dirty fluids started to ooze out these smelly containers. It was reported that the environmental and customs officials even refused to open these containers as it was unsafe to do so. It was also reported that the garbage consignments moved from the port to the BOI were not physically checked by the Customs and other regulatory agencies, and these agencies did not conduct any entry processing or check on documents, due to BOI regulations! Though the Finance Minister promised the Parliament, in July 2019, that he would conduct a comprehensive investigation into the matter and would take legal action against the culprits nothing much had happened even after four years. It is also noteworthy that these garbage containers were discovered only after the collapse of Meethotamulla Garbage Dump in 2017. If Meethotamulla had not imploded, at least some of the waste may have ended up there.

Sri Lanka – Singapore FTA

The SLSFTA was negotiated at a time when the global crisis in the garbage trade was at its peak. So, how did Sri Lankan negotiators react to the crisis? Did they see it as a threat or an opportunity? Trade negotiators are expected to analyse trade statistics before making any commitment on any tariff line. Didn’t they know that Sri Lanka was already importing plastic waste? The representatives from the BOI were involved in the negotiations. Didn’t they know Sri Lanka had established these “resource recovery industries” within the BOI? How Singaporean negotiators approached this issue. Did they request any commitments from Sri Lanka in the area of import and processing of waste? Did we provide these commitments without any requests? And finally, didn’t they even know that Sri Lanka made these commitments?

The SLSFTA was negotiated at a time when the global crisis in the garbage trade was at its peak. So, how did Sri Lankan negotiators react to the crisis? Did they see it as a threat or an opportunity? Trade negotiators are expected to analyse trade statistics before making any commitment on any tariff line. Didn’t they know that Sri Lanka was already importing plastic waste? The representatives from the BOI were involved in the negotiations. Didn’t they know Sri Lanka had established these “resource recovery industries” within the BOI? How Singaporean negotiators approached this issue. Did they request any commitments from Sri Lanka in the area of import and processing of waste? Did we provide these commitments without any requests? And finally, didn’t they even know that Sri Lanka made these commitments?

When I warned that plastic and asbestos waste will be imported for processing and recycling, the Ministry of Development Strategies and International Trade responded by stating “… in order for products manufactured in Singapore using non-originating raw materials (imported raw materials) to become eligible for Customs duty concessions under SLSFTA, origin criteria listed below should be complied with: I. Sufficient working or processing + comply with value addition of 35% of FOB or II. Sufficient working or processing + comply with CTH (change of tariff no at 4- digit level between the finished product and imported inputs) or… Sufficient working or processing + comply with Product Specific Rules”),” (“Garbage in, Garbage out’- Malik’s response,” The Island, October 9, 2018).

Unfortunately, our trade negotiators and advisers are not even aware that under the SLSFTA Rules of Origin, waste and scrap for recycling qualify as wholly obtained products, like plants … grown and harvested, or live animals born, raised and slaughtered in Singapore. The relevant sections are Article 4 k, l, and m, which state” … (k) used articles collected there fit only for the recovery of raw materials; (l) wastes and scrap resulting from manufacturing operations conducted there; (m) waste and scrap derived from used goods collected in the exporting Party, provided that those goods are fit only for the recovery of raw materials.“ Under these sub- articles plastic waste, asbestos waste and similar products, can be imported for the recovery of raw materials by the “resource recovery industry” which had a highly lucrative operation in the BOI zones when the agreement was signed.

The agreement clearly categorises waste collected in Singapore as a wholly obtained product under Article 4, the Ministry of DS& IT claimed waste cannot be imported under Article 5. Didn’t our International Trade Ministry and other trade “experts” understand waste collected in Singapore is covered under Article 4 and hence the limitations in Article 5 do not apply? Or was it a deliberate attempt to hoodwink the public?

Then there are a few specific rules of origin that would facilitate the dumping of dangerous products in Sri Lanka. For example, crocidolite asbestos (HS 6812) also known as blue asbestos, is considered the most hazardous type of asbestos. Sri Lanka prohibited the use of crocidolite asbestos in 1987. Singapore banned the use of all types of Asbestos in 1989. However, a significant amount of the material remains in the buildings and elsewhere in Singapore and there are strict laws governing the demolishing and removal of these materials. Shockingly this item is not only included in Sri Lanka’s TLP but our negotiators have spent time and money on formulating very simple specific rules of origin to facilitate its imports. If a product containing Crocidolite, simply changes its tariff subheading then it qualifies as a product of Singaporean origin.

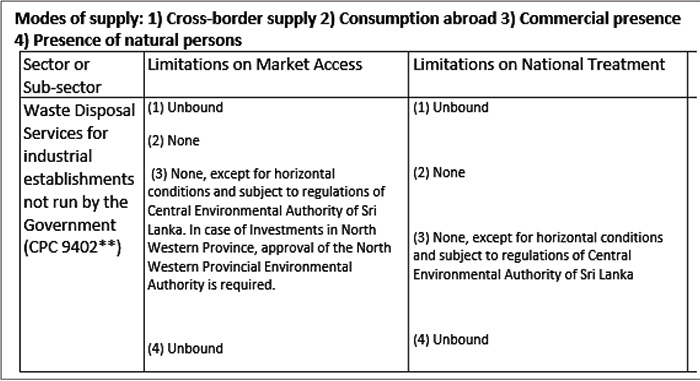

Then in the Services Chapter Sri Lanka has undertaken a specific commitment on Waste Disposal Services which is reproduced below (see Table 3):

The CPC 9402 refers to “refuse collection and disposal services’ and it includes collection services of garbage, trash, rubbish and waste, whether from households or from industrial and commercial establishments, transport services and disposal services by incineration or by other means. The use of “**” against the CPC code indicates that the specific commitment for that code shall not extend to the total range of services covered under that code. Sri Lanka’s commitment clearly limits its scope to waste collected from industrial establishments not run by the Government, but no other areas are excluded.

Under these commitments, services can be provided through four modes of supply. For “Waste Disposal Services” Sri Lanka has opened up only two modes of supply, namely, Mode 2) Consumption abroad and Mode 3) Commercial presence. The term “None” under this commitment means that the country is committing itself to provide full liberalization without any limitations on market access or national treatment for the service sector and modes of supply for which commitments are written.

By opening up Mode 2 without any restrictions, Sri Lanka permits the other party to the agreement to process its solid waste in Sri Lanka. If the intention of Sri Lankan negotiators, as the government claims, was to limit this to waste collected in Sri Lanka, then mode 2 should have been left unbound. By opening up of Mode 3 Sri Lanka has allowed Singaporean Waste Disposal Services to establish a subsidiary in Sri Lanka, subject to regulations of the Central Environmental Authority of Sri Lanka. Therefore, under this commitment waste can be imported from Singapore not only to recover raw materials but also to dispose of.

Before the SLSFTA entered into force in May 2018, if a Singaporean, Chinese or any other national wanted to recycle imported waste in Sri Lanka, it was possible to do so under BOI regulations. After May 2018, any Singaporean company can establish refuse disposal services in Sri Lanka, under the commitments undertaken by Sri Lanka in the services chapter of the SLSFTA, to recycle and/or process waste!

After I raised this issue it was widely discussed. I believe the Presidential Commission also recommended that the articles which permit waste import and recycling should be amended. My article “SL chosen as garbage dump by Singapore after China etc. shut their doors,” published in the Island in 2018, was tabled in the parliament by Shehan Semasinghe. Later, in April 2022, he became the Minister of Trade and since September 2022 he is the Minister of State for Finance. In spite of all that the government had not taken any action to protect Sri Lanka from becoming a garbage dump for developed countries other than calling my claim, “… a despicable attempt … to deceive the public” and in turn releasing few press releases with incorrect information to mislead the public. Even when the government imposed a ban on imports of hundreds of products, waste items like plastic waste were not included in that list and every year Sri Lanka continues to import thousands of tons of plastic waste!

In 2019, the Philippines, in a major diplomatic row with Canada, reshipped 2,400 tonnes of Canadian toxic waste which was imported labelled as plastic waste for recycling. Other countries in the region also had taken similar action. But we in Sri Lanka are not like that. Last year alone Sri Lanka imported over 6000 tons of plastic waste! Most of it came from China, a country that banned the import of plastic waste to protect environmental interests and people’s health and safety.

(The writer can be contacted via senadhiragomi@gmail.com.)

Opinion

The Rule of Law from a Master of the Rolls and Lord Chief Justice of England

These last few months have given us vivid demonstrations of the power of the Rule of Law. A brother of the reigning monarch in Great Britain has been arrested by the local police and questioned. This is reported to be the first time since 1647 (Charles I) that a person so close in kin to the reigning monarch was arrested by the police in England. An ambassador of the United Kingdom who also was a member of the House of Lords has been questioned by the police because of alleged abuse of office. In US, the Supreme Court has turned back orders of a President who imposed new tariffs on imports into that might trading nation. A nation that was made by law (the Constitution) again lived by the rule of law and not by the will of a ruler, so avoiding the danger of dictatorship.

In Sri Lanka, once high and mighty rulers and their kith and kin have been arrested and detained by the police for questioning. A high ranking military official has been similarly detained. Comments by eminent lawyers as well as by some cantankerous politicians have cited the services rendered by these worthies as why they should be treated differently from other people who are subject to the rule of laws duly enacted in that land. In Sri Lanka governments, powerful politicians and bureaucrats have denied the rule of law by delaying filing cases in courts of law, until the physical evidence is destroyed and the accused and witnesses are incapacitated from partaking in the trial. These abuses are widely prevalent in our judicial system.

As the distinguished professor Brian Z. Tamanaha, (On the Rule of Law, 2004.) put it “the rule of law is ‘an exceedingly elusive notion’ giving rise to a ‘rampant divergence of understandings’ and analogous to the notion of Good in the sense that ‘everyone is for it, but have contrasting convictions about what it is’. The clearest statement on the rule of law, that I recently read as a layman, came in Tom Bingham (2010), The Rule of Law (Allen lane). Baron Bingham of Cornhill was Lord Chief Justice of England from 1996 until his retirement. For the benefit of your readers, I reproduce a few excerpts from his short book of 174 pages.

“Dicey (A.V.Dicey, 1885) gave three meanings to the rule of law. ‘We mean, in the first place… that no man is punishable or can be made to suffer in body or goods except for a distinct breach of law established in the ordinary legal manner before the ordinary courts of the land.’…If anyone -you or I- is to be penalized it must not be for breaking some rule dreamt up by an ingenious minister or official in order to convict us. It must be for proven breach of the established law and it must be a breach established before the ordinary courts of the land, not a tribunal of members picked to do the government’s bidding, lacking the independence and impartiality which are expected of judges.

” We mean in the second place, when we speak of ‘the rule of law’ …..that no man is above the law but that every man, whatever his rank or condition, is subject to the ordinary law of the realm and amenable to the ordinary tribunals.’ Thus no one is above the law, and all are subject to the same law administered in the same courts. The first is the point made by Dr Thomas Fuller (1654-1734) in 1733: ‘Be you ever so high, the law is above you.’ So, if you maltreat a penguin in the London Zoo, you do not escape prosecution because you are Archbishop of Canterbury; if you sell honours for a cash reward, it does not help that you are Prime Minister. But the second point is important too. There is no special law or court which deals with archbishops and prime ministers: the same law, administered in the same courts, applies to them as to everyone else.

“The core of the existing principle is, I suggest, that all persons and authorities within the state, whether public or private, should be bound by and entitled to the benefits of laws publicly made, taking effect (generally) in the future and publicly administered in the courts. … My formulation owes much to Dicey, but I think it also captures the fundamental truth propounded by the great English philosopher John Locke in 1690 that ‘Wherever law ends, tyranny begins’. The same point was made by Tom Paine in 1776 when he said ‘… in America THE LAW IS KING’. For, as in absolute governments the King is law, so in free countries the law ought to be King; and there ought to be no other.’

“None of this requires any of us to swoon in adulation of the law, let alone lawyers. Many people occasion share the view of Mr. Bumble in Oliver Twist that ‘If the law supposes that ….law is a ass -a idiot’. Many more share the ambition of expressed by one of the rebels in Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part II, ‘The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers. ….’. The hallmarks of a regime which flouts the rule of law are, alas, all too familiar: the midnight knock on the door, the sudden disappearance, the show trial, the subjection of prisoners to genetic experiment, the confession extracted by torture, the gulag and the concentration camp, the gas chamber, the practice of genocide or ethnic cleansing, the waging of aggressive war. The list is endless. Better to put up with some choleric judges and greedy lawyers.”

Tom Bingham draws attention to a declaration on the rule of law made by the International Commission of Jurists at Athens in 1955:

=The state is subject to the law;

=Government should respect the rights of individuals under the Rule of Law and provide effective means for their enforcement;

=Judges should be guided by the Rule of Law and enforce it without fear or favour and resist any encroachment by governments or political parties in their independence as judges;

=Lawyers of the world should preserve the independence of their profession, assert the rights of an individual under the Rule of Law and insist that every accused is accorded a fair trial;

The final rich paragraph of the book reads as follows: ‘The concept of the rule of law is not fixed for all time. Some countries do not subscribe to it fully, and some subscribe only in name, if that. Even those who subscribe to it find it difficult to subscribe to all its principles quite all the time. But in a world divided by differences of nationality, race, colour, religion and wealth it is one of the greatest unifying factors, perhaps the greatest, the nearest we are likely to approach to a universal secular religion. It remains an ideal, but an ideal worth striving for, in the interests of good government and peace, at home and in the world at large.’

by Usvatte-aratchi ✍️

Opinion

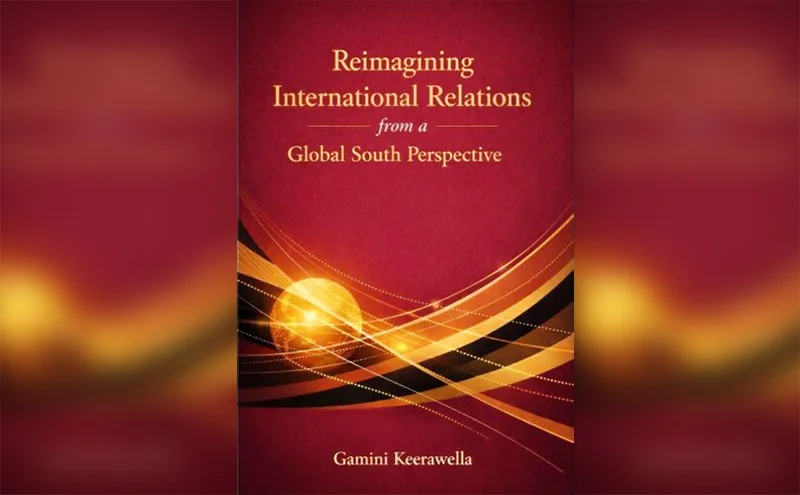

Reimagining International Relations from a Global South Perspective

I wish to congratulate Prof. Keerawella, for having undertaken this mammoth task of seeking to capture, from ‘a global south perspective’, the multiple facets of scholarship of International Relations. He has, as always, been meticulous in his research, and also lucid in conveying to the reader, complex ideas and their interconnections, in an uncomplicated way. I am not in the habit of encouraging taking shortcuts, particularly with my students around – but if pressed, here is a book, with references to every major scholar in the 7 areas identified, in 440 pages, at a modest price.

We are honoured that the Prime Minister graced this occasion, and thankful for her inspiring words. She has left much food for thought – which I am hopeful our students will consider engaging with, as they proceed with their presentations and dissertations.

This is the 7th book, in fact the 3rd authored or co-authored by Prof. Keerawella, published under the auspices of the BCIS, over the past couple of years. It is a reflection of BCIS’s continuing commitment to bring into the public domain, quality academic literature that benefits both scholars and Sri Lankan students who pass through these halls and beyond. I want to commend President Kumaratunga, for through the BCIS, continuing to support the publication of such texts, at a time individually doing so is prohibitive and also more costly to the buyer, and the Bandaranaike Memorial National Foundation (BMNF) for making this possible.

Turning to the volume launched today (24 Feb), in ‘Reimagining International Relations from a Global South Perspective’, at the outset, Prof. Keerawella makes clear that a Global South perspective is not simply a matter of geographical focus; it is an epistemic stance that seeks to recover marginalised voices, experiences, and knowledge that have long been silenced or subordinated in mainstream discourse. He goes on to emphasise that, the choice of the phrase “a Global South Perspective” is deliberate. It signals an awareness that there is no single, homogeneous standpoint from which the Global South speaks’. To speak of a perspective, then, is to situate this volume’s argument within that broader, evolving mosaic—to offer one possible articulation among many, without claiming representational authority over them. Prof. Keerawella emphasises, it is an invitation to dialogue, not a declaration of orthodoxy.

As is customary by a reviewer, I intend to take up Prof. Keerawella’s ‘invitation to dialogue’ and commencsation in the latter part of this presentation, but first let me outline the valuable insights contained in this Book, as an appetiser.

The first chapter on IR Theory, points out – in each of the ‘isms’, ingredients as it were, that could contribute to a better understanding of the ‘Global South’. Here he highlights Raúl Prebisch and Andre Gunder Frank’s ‘dependency theory’, Neta Crawford’s ‘normative constructivism’, Sanjay Seth’s ‘Decolonial Critique’ and Amitav Acharya’s concept of ‘Global IR’ as having advanced a reformist, yet transformative agenda for the discipline. He observes that, “Collectively, their respective projects of rethinking, decolonizing, and globalizing International Relations illuminate how the Global South can contribute to the field not merely as a repository of empirical cases, but as a source of conceptual reflection and theoretical innovation”.

The second chapter which examines the transformation of International Security Studies, by foregrounding the lived insecurities of the Global South—ranging from poverty and structural violence to environmental vulnerability and social fragility, demonstrates why concepts such as human security gained salience as corrective and complementary frameworks, concerning the global south.

The third chapter pays analytical attention to the dynamics of regionalism with special focus on South Asia and the experience of the SAARC. It calls for reimagining regional cooperation in South Asia beyond rigid institutional templates, advocating for inclusive, flexible, and people-centered modalities rooted in the specific political and social realities of the Global South.

The fourth chapter addresses international organisations and international regimes as central pillars of contemporary global governance, with particular attention to their implications for the Global South. The chapter reveals how Global South states have simultaneously been constrained by inherited governance structures and mobilized collective strategies to contest inequities and assert greater voice.

The fifth chapter which focuses on Foreign Policy Analysis (FPA), situates it within a rapidly evolving global environment shaped by globalisation, technological transformation, and the Fourth Industrial Revolution, paying particular attention to the strategic choices made by Global South states.

The sixth chapter traces the long historical arc of diplomatic practice, demonstrating how modes of representation, negotiation, and cooperation have evolved in response to changing political, social, and technological contexts. From a Global South perspective, the chapter underscores both the opportunities and constraints of particularly science diplomacy.

In the final chapter, Prof. Keerawella discusses the notion of national self-determination.

He underscores its contradictions in theory, and its praxis in the post-Cold War context, tracing the ways in which self-determination has been invoked and contested in modern international relations.

Besides joining a very small league of international scholars (some already referred to) who have dared to challenge Western theoretical approaches in the study of IR and sub-fields and emphasised the need for an alternative ‘Global South’ reading, Prof. Keerawella becomes the first Sri Lankan to do so in any considered manner. His volume is also rare, in that in general, few Sri Lankans have sought to engage with and contribute to the theoretical literature of International Relations and Foreign Policy. His book has the additional advantage of being released at a time ‘International Relations’ – as we have been taught it and understood it, is under severe strain to explain contemporary developments in a conceptual and theoretical manner, and there is a serious vacuum to be filled, not just in understanding, but in order to change the currentpredicament.

While the book reaffirms the ‘global south’ as a certain collective sentiment, assembling many of the conceptual building blocks and empirical insights necessary for its articulation, what it leaves to us is the task of synthesising these elements into a coherent and operational set of principles that can foster a unified front amongst the Global South, despite the vast diversity of the actors and states involved.

While I have no disagreement with Prof. Keerawella’s starting premise and end goal of the desirability of having ‘a Global South Perspective’ in the areas under study, however, as an observer and practitioner of international relations for most of my professional life since 1980

– 9 years as a journalist, 33 years as a diplomat, and post-retirement, and over 4 years from the vantage point of running IR and Strategic Studies focused institutions, while also teaching, and engaging in my own research, I do encounter some difficulty, and lament that operationally little has or is being done, to evolve a strategy that addresses the shortcomings so carefully pointed out in Prof. Keerawella’s book.

Looking back, I do not see a single cohesive ‘Global South’ consistently in play. Rather, I see a multitude of ‘Global Souths’ –depending on the issue, competing opportunistically and often working at cross purposes, and all eventually getting played out by the continuing structural heft of the ‘Global North’.

This is no fault of Prof. Keerawella, or of the rich ingredients he brings together in this volume. Rather, it reflects the political reality that the‘Global South’ recipe has not yet been fully translated into an appetising dish.

I am no chef, and time does not permit me to elaborate from the different vantagespoints

I have experienced it from – but I do believe there is a compelling case that could be made for action, which needs serious reflection and attention.

To put it another way, without making value judgements on the rights and wrongs of the respective action, I wish to pose two sets of questions, confining myself to events of the past 4 years or so;

First, what did the ‘Global South’ do in the cases of Ukraine since 2022, of Gaza since 2023, of Sudan since 2023, on actions in the South-China Sea in recent times, following the imposition of ‘Reciprocal Tariffs’ throughout 2025, or in the case of Venezuela last month?

* Did they speak together?

* Did they vote together?

* Did they fight together?

Similarly, second, what will the ‘Global South’ do, God forbid, if there is to be a conflict on Iran, Cuba, the Panama Canal, Morocco-Algeria, DRC-Rwanda, or Taiwan, tomorrow?

* Will they speak together?

* Will they vote together?

* Will they fight together?

If I were to play devil’s advocate, I would be tempted to ask: if these coalitions neither speak, vote, nor act together, what kind of analytical and normative work can the category ‘Global South’ realistically achieve? Rather than assuming a unity that does not yet exist, how might we need to refine it?

To this end, I wish to posit, that the category of ‘Global South’ could be analytically more useful, if, as Max Weber suggested, it be used as an ‘ideal type’ – that might not be realized, but must be sought to be approximated.’Global South’ functions best as a Max Weber-inspired ‘ideal type’: an abstract model used not as a description of an existing state, but as a heuristic tool to clarify the degree to which specific regions approximate or diverge from its core characteristics.

Such an approximation cannot merely be imagined; it has at least to be attempted in practice.

What I am suggesting is not utopian. Historically, there is precedent that has been realized by the Non-Aligned group of countries – which by no means perfect, but was effective in its heyday duringthe 1960s, 1970s, and early 1980s. Unfortunately, rather than being reformed and modified at the end of the Cold War, it has been tossed away.

Admittedly, those were different times, but for purposes of encouraging the dialogue and debateProf. Keerawella wanted us to have stemming from his book, and in order to draw inspiration, let me suggest 4 factors that made Non-Alignment work as an operational strategy, while it did;

* There was a clearer ‘Framework of Operation’ – the Non-Aligned MOVEMENT, which incidentally in this year we commemorate the 50th anniversary of the hosting of the 5th Summit in Sri Lanka in 1976 at this very venue the BMICH.

* There was also a clear ‘Other’ – the cold War driven Western alliance on the one hand, and the Warsaw pact countries, which had competing ideologies–and which broadly Non-Aligned countries preferred not to emulate in toto.

* There was further an alternate Politico-Economic and Legally grounded Agenda – which saw expression through the UN Special Session on Disarmament, an operationally stronger UNCTAD, and a international legal regimethe UN Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), inwhich NAM countries played crucial roles.

* There was also ‘a like-minded collective leadership’ – which, spare a few, more often than not, dared to demonstrate objectivity between the West and the East – and resisted being unquestioning followers. Though they might not have been loved by the ‘West’, or for that matter by the ‘East’, but they were broadly respected by both.

While newer formations such as the G77, the BRICS, the SCO, alongside regional groupings such as the RCEP, the ASEAN, the AU, the GCC, and BIMSTEC have sought to fill this space, they remain, at best, partial substitutes, lacking the normative coherence and political solidarity that characterized the early NAM efforts that resulted in effective collective action demands.

It is ironic, that at a time when the ‘Global North’ is in disarray, and some its own constituents have made bold to say that this is not a “transition” but a “rupture” of the US-led rules-based international order, that there is no cohesive ‘Global South’ alternative.

The real question before the ‘Global South’ today should be, as to what conditions and mechanism could lead us to position ourselves better, to consolidate such a collective, and most importantly whether there is the political will to do so?

If not, we must at least be honest about current limits – that many states with even some capacity, are compelled to hedge, while those without meaningful leverage remain largely ‘bystanders’ in the global order.

However, if we recognize that this situation is not tenable and that we wish to serve a higher cause, we should do something about it and try to create ‘sufficient conditions’ that could more actively and tangibly approximate ‘a Global South’- which can ‘bracket’ its differences, find unity in what is most important, and avoid the temptation of flirting for temporary gain or glory.

This is the thought I wish to leave you with today in the hope that, as envisaged by Prof. Keerawella, this volume will not be the last word on ‘a Global South perspective’, but a starting point for precisely the kind of critical, self-reflective conversation that can turn it into a more grounded, plural, and effective practical programme and call to action.

Speech delivered by

by Ambassador (Retd.)

Ravinatha Aryasinha,

former Foreign Secretary and Executive Director, Regional Centre for Strategic Studies (RCSS), at the launch of

Prof. Gamini Keerawella’s book ‘Reimagining International Relations from a Global South Perspective’,

at the Bandaranaike Centre for International Studies (BCIS), Colombo on 24 February 2026)

Opinion

The J.R. I Disliked — A Review of Courage, Candour and Historical Balance

The latest addition to the “Historic Thoughts” series by the J. R. Jayewardene Centre arrives with a provocative title: The J.R. I Disliked by Imthiaz Bakeer Markar. Yet beneath its seemingly adversarial framing lies a reflective and intellectually honest reassessment of one of Sri Lanka’s most consequential political figures — J. R. Jayewardene.

This publication, based on a commemorative lecture, is not merely a memoir fragment. It is a political meditation on leadership, ideological evolution, and the necessity of historical sobriety in a time when public discourse is often driven by caricature rather than careful analysis.

Candour as Political Virtue

What immediately distinguishes Markar’s lecture is its rare tone of sincerity. He openly recalls that, as a young activist, he seconded a proposal to expel Jayewardene from the United National Party — a confession that gives the work unusual credibility. In Sri Lankan political culture, where retrospective loyalty often replaces honest memory, such candour is refreshing.

Markar’s narrative demonstrates a crucial democratic lesson: political disagreement need not devolve into permanent enmity. His recollection of Jayewardene’s magnanimity — promoting a former critic based on merit rather than loyalty — reveals a statesman confident enough to transcend factional bitterness. This alone makes the publication politically instructive for a generation accustomed to zero- sum politics.

Beyond the Right–Left Caricature

One of the most valuable contributions of this text is its implicit challenge to the simplistic labeling of Jayewardene as merely a “right-wing” leader. A careful reading of Jayewardene’s own parliamentary interventions supports this reassessment.

As early as the 1940s, he warned:

“We are suffering due to an administrative system established and protected by foreign rulers… Until we are freed from this imperialist and capitalist administrative system, we will not… resolve the serious issues we face.”

This is not the language of doctrinaire capitalism. Nor was Jayewardene drawn to orthodox Marxism. Instead, his political philosophy reflected what may best be described as a pragmatic middle path — informed, arguably, by Buddhist political ethics that molded his own life.

He himself signaled this balance when he insisted Sri Lanka must learn from global systems without surrendering autonomy. His famous reply to U.S. pressure over the rubber-rice trade remains instructive:

“We do not compromise our independence in exchange for aid… from the United States or any other country.”

In an era when small states again face geopolitical bargaining pressures, this principle retains striking relevance.

Architect of Transformative Pragmatism

Markar is at his strongest when recounting Jayewardene’s political resilience. The rebuilding of the UNP after the 1956 defeat, the strategic patience during opposition years, and the eventual 1977 mandate illustrate what John F. Kennedy called “discipline under continuous pressure.”

Historically, Jayewardene’s policy legacy is too significant to be reduced to partisan memory. His role in:

· opening the economy

· establishing free trade zones

· expanding irrigation and electrification

· strengthening free education through textbooks and Mahapola

· modernising communications and infrastructure collectively altered Sri Lanka’s development trajectory.

Critics may debate the social costs of liberalisation, but no serious historian can deny the structural transformation that followed 1977. Markar rightly reminds us that many revenue streams and institutional pathways Sri Lanka relies on today originated in that reform moment.

The Independence Question Revisited

Perhaps the most intellectually compelling sections of the lecture revisit Jayewardene’s pre-independence thought. His insistence — alongside D. S. Senanayake — that Ceylon’s participation in World War II must be tied to a guarantee of freedom reveals remarkable foresight.

Equally revealing is his humanistic vision:

“Landlessness, poverty and hunger cannot be eradicated… until every vestige of foreign rule is swept away… so that English, Indian, Dravidian, etc. can work hand-in-hand.”

Here we see a leader whose nationalism was not exclusionary but developmental and pluralist — a nuance often lost in contemporary polemics.

International Realism Without Subservience

Markar’s discussion of the 1951 San Francisco Peace Conference is particularly important for younger scholars. Jayewardene’s invocation of the Buddhist maxim “Nahi verena verani” in defence of Japan’s dignity was not rhetorical flourish; it was strategic moral diplomacy.

Likewise, his firm response to foreign pressure over Sri Lanka’s trade choices demonstrates a foreign policy posture that was neither isolationist nor submissive — but sovereignly pragmatic.

In today’s multipolar uncertainty, Sri Lanka could profit from revisiting this calibrated realism.

The Necessary Balance

To his credit, Markar does not canonise Jayewardene. He acknowledges criticisms — authoritarian tendencies, the referendum extension, media tensions. This intellectual honesty strengthens rather than weakens his overall argument.

History, after all, is not served by hagiography.

Yet the broader point of the publication — and one I strongly endorse — is that Sri Lanka’s public discourse has too often magnified Jayewardene’s flaws while neglecting the scale of his statecraft. Serious scholarship demands proportionality.

Why This Book Matters Now

At a time when historical study in Sri Lanka risks being flattened by partisan narratives and social-media simplifications, The J.R. I Disliked performs a valuable civic function. It models three urgently needed habits:

Intellectual humility

— the willingness to revise earlier judgments Political generosity — recognising merit across factional lines Historical balance — weighing achievements alongside failures

For younger Sri Lankans especially, the work is a reminder that national development is rarely the product of ideological purity. It is, more often, the outcome of pragmatic adaptation — something Jayewardene understood deeply.

Final Assessment

This slim publication succeeds precisely because of its honesty. Markar’s journey from youthful critic to reflective admirer mirrors the maturation Sri Lanka’s own political analysis must undergo.

Whatever one’s partisan position, the evidence remains compelling: Jayewardene was among the most consequential executive leaders in our post-independence history — a statesman who sought, with notable pragmatism, to position Sri Lanka for social, economic and international advancement.

If this volume encourages a new generation to study his record with intellectual seriousness rather than inherited prejudice, it will have performed a national service.

And in that sense, the “J.R. he once disliked” may yet become the J.R. a thoughtful nation learns to understand more fully.

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoBrilliant Navy officer no more

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoSri Lanka – world’s worst facilities for cricket fans

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoA life in colour and song: Rajika Gamage’s new bird guide captures Sri Lanka’s avian soul

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCabinet nod for the removal of Cess tax imposed on imported good

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoOverseas visits to drum up foreign assistance for Sri Lanka

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoSri Lanka to Host First-Ever World Congress on Snakes in Landmark Scientific Milestone

-

Latest News2 days ago

Latest News2 days agoAround 140 people missing after Iranian navy ship sinks off coast of Sri Lanka

-

News1 day ago

News1 day agoLegal experts decry move to demolish STC dining hall