Features

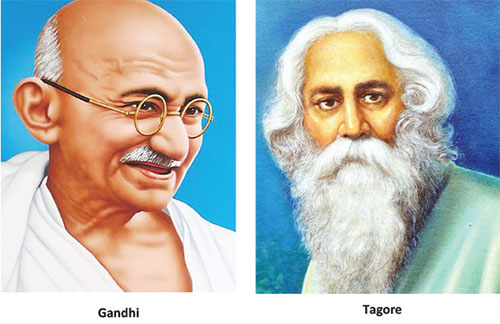

Eminent Indians in Galle

In November 1927, Mahatma Gandhi and Kasturbai Gandhi arrived in Galle. They were the chief guests at the prize-giving of Mahinda College, on the 24th. The Olcott Memorial Assembly Hall of the College was filled to capacity. Never was there such a large gathering of Buddhists, Hindus and Christians. The speech given by Gandhi is excerpted from the Mahinda College Magazine of 2002:

“It has given me the greatest pleasure to be able to be present at this very pleasant function. You have paid me, indeed, a very great compliment and conferred on me a great honour by allowing me to witness your proceedings and making the acquaintance of so many boys.

I hope that this institution will progressively expand as, I have no doubt, it deserves. I have come to know enough of this beautiful Island and its people to understand that there are Buddhists enough in this country, not merely to support one such institution, but many such institutions. I hope, therefore, that this institution will never have to pine for want of material support, but having known something of the educational institutions both in South Africa and India, let me tell you that scholastic education is not merely brick or mortar. It is true boys and true girls who build such institutions from day to day. I know some huge architecturally perfect buildings going under the name of scholastic institutions, but they are nothing but whited sepulchres. Conversely, I know also some institutions which have to struggle from day to day for their material existence, but which, because of this very want, are spiritually making advance from day to day. One of the greatest teachers that mankind has ever seen and one whom you have enthroned as the only Royal Monarch in your hearts, delivered his living message not from a man-made building, but under the shadow of a magnificent tree. May I also venture to suggest that the aim of a great institution like this should be to impart such instruction and in such ways that it may be open to any boy or girl in Ceylon.

“I notice already that, as in India, so in this country, you are making education daily more and more expensive so as to be beyond the reach of the poorest children. Let us all beware of making that serious blunder and incurring the deserved reproach of posterity. To that end let me put the greatest stress upon the desirability of giving these boys instruction from A to Z through the Sinhalese language. I am certain that the children of the nation that receive instruction in a tongue other than their own commit suicide. It robs them of their birth right. A foreign medium means an undue strain upon the youngsters; it robs them of all originality. It stunts their growth and isolates them from their home. I regard therefore such a thing as a national tragedy of first importance, and I would like also to suggest that since I have known Sanskrit in India as the mother language, and since you have received all religious instruction from the teachings of one who was himself an Indian amongst Indians and who had derived his inspiration from Sanskrit writings that it would be but right on your part to introduce Sanskrit as one of the languages that should be diligently studied. I should expect an institution of this kind to supply the whole of the Buddhist community in Ceylon with text books written in Sinhalese and giving all the best from the treasures of old. I hope that you will not consider that I have placed before you an unattainable ideal. Instances occur to me from history where teachers have made Herculean efforts in order to restore the dignity of the mother-tongue and to restore the dignity of the old treasures which were about to be forgotten.

“I notice already that, as in India, so in this country, you are making education daily more and more expensive so as to be beyond the reach of the poorest children. Let us all beware of making that serious blunder and incurring the deserved reproach of posterity. To that end let me put the greatest stress upon the desirability of giving these boys instruction from A to Z through the Sinhalese language. I am certain that the children of the nation that receive instruction in a tongue other than their own commit suicide. It robs them of their birth right. A foreign medium means an undue strain upon the youngsters; it robs them of all originality. It stunts their growth and isolates them from their home. I regard therefore such a thing as a national tragedy of first importance, and I would like also to suggest that since I have known Sanskrit in India as the mother language, and since you have received all religious instruction from the teachings of one who was himself an Indian amongst Indians and who had derived his inspiration from Sanskrit writings that it would be but right on your part to introduce Sanskrit as one of the languages that should be diligently studied. I should expect an institution of this kind to supply the whole of the Buddhist community in Ceylon with text books written in Sinhalese and giving all the best from the treasures of old. I hope that you will not consider that I have placed before you an unattainable ideal. Instances occur to me from history where teachers have made Herculean efforts in order to restore the dignity of the mother-tongue and to restore the dignity of the old treasures which were about to be forgotten.

“I am glad indeed that you are giving due attention to athletics and I congratulate you upon acquitting yourselves with distinction in games. I do not know whether you had any indigenous games or not. I should, however, be exceedingly surprised and even painfully surprised, if I were told that before cricket and football descended upon your sacred soil, your boys were devoid of all games. If you have national games, I would urge upon you that yours is an institution that should lead in reviving old games. I know that we have in India noble indigenous games just as interesting and exciting as cricket or football, also as much attended with risks as football is, but with the added advantage that they are inexpensive, because the cost is practically next to nothing.

“I am no indiscriminate superstitious worshipper of all that goes under the name of ‘ancient’. I never hesitated to endeavour to demolish all that is evil or immoral, no matter how ancient it may be, but with this reservation. I must confess to you that I am an adorer of ancient institutions and it hurts me to think that a people in their rush for everything modern despise all their ancient traditions and ignore them in their lives.

“We of the East very often hastily consider that all that our ancestors laid down for us was nothing but a bundle of superstitions, but my own experience, extending now over a fairly long period of the inestimable treasures of the East has led me to the conclusion that, whilst there may be much that was superstitious, there is infinitely more which is not only not superstitious, but if we understand it correctly and reduce it to practice, gives life and ennobles one. Let us not therefore be blinded by the hypnotic dazzle of the West.

“Again, I wish to utter a word of caution against your believing that I am an indiscriminate despiser of everything that comes from the West. There are many things which I have myself assimilated from the West. There is a very great and effective Sanskrit word for that particular faculty which enables a man always to distinguish between what is desirable and what is undesirable, what is right and what is wrong, that word is known as ‘Viveka’. Translated into English, the nearest approach is discrimination. I do hope that you will incorporate this word into Pali and Sinhalese

“There is one thing more which I would like to say in connection with your syllabus. I had hoped that I should see some mention made of handicrafts, and if you are not seriously teaching the boys under your care some handicrafts, I would urge you if it is not too late, to introduce the necessary handicrafts known to this Island. Surely, all the boys who go out from this institution will not expect or will not desire to be clerks or employees of the Government. If they would add to the national strength, they must learn with great skill all the indigenous crafts, and as cultural training and as the symbol of identification with the poorest among the poor, I know nothing so ennobling as hand spinning. Simple as it is, it is easily learnt. When you combine with hand spinning the idea that you are learning it not for your own individual self, but for the poorest among the nation, it becomes an ennobling sacrament. There must be added to this sacrament some occupation, some handicraft which a boy may consider will enable him to earn his living in later life.

You have rightly found place for religious instruction. I have experimented with quite a number of boys in order to understand how best to impart religious instruction and whilst I found that book instruction was somewhat of an aid, by itself it was useless. Religious instruction, I discovered, was imparted by teachers living the religion themselves. I have found that boys imbibe more from the teachers’ own lives than they do from the books that they read to them, or the lectures that they deliver to them with their lips. I have discovered to my great joy that boys and girls have unconsciously a faculty of penetration whereby they read the thoughts of their teachers. Woe to the teacher who teaches one thing with his lips, and carries another in his breast.

“Now, just one or two sentences to boys only and I have done. As father of, you might say, many boys and girls, you might almost say of thousands of boys and girls, I want to tell you, boys, that after all you hold your destiny in your own hands. I do not care what you learn or what you do not learn in your school, if you will observe two conditions. One condition is that you must be fearlessly truthful against the heaviest odds under every circumstance imaginable. A truthful boy, a brave boy will never think of hurting even a fly. He will defend all the weak boys in his own school and help, whether inside school or outside the school, all those who need his help. A boy who does not observe personal purity of mind and body and action, is a boy who should be driven out of any school. A chivalrous boy would always keep his mind pure, his eyes straight and his hands unpolluted. You do not need to go to any school to learn these fundamental maxims of life, and if you will have this triple character with you, you will build on a solid foundation.

“May then true ahimsa and purity be your shield forever in your life. May God help you to realize all your noble ambitions, I thank you once more for inviting me to take part in this function!”

The following day Gandhi was to entrain at the Galle Railway Station, when he was informed that large crowds had gathered along the route to see him. Then he asked, “What am I to do?” “People will be delighted, if you could walk to the Railway Station.” “All right,” said Gandhi. “I will then walk the distance.” It was an uphill task for the police to manage the crowds.

In 1922, Dr. Rabindranath Tagore of Shantiniketan fame also visited Mahinda College. Here is an excerpt from the Mahinda College magazine. ‘The poet arrived at Mahinda College by car, about 2 pm on October 17th, 1922 accompanied by Mr. C. F. Andrews and Dr. W. A. de Silva. The boys had been eagerly looking forward to his visit, for it had been arranged many months before, when it had been first known that he was to come to Ceylon.

After about an hour’s rest, the poet came into the big Olcott Hall, where all the boys were assembled to greet him. He was then garlanded by the oldest member of the staff, Pandit G. Sagaris de Silva, and, in order to avoid his having to speak loudly, all the younger boys came up close to the dais and sat on the floor around his feet.’

The speech delivered by him on the occasion is given below.

“My young friends, I do not like to stand on a high platform and speak to you as a distinguished guest. I want to move freely amongst you and be your companion. I wish I could stay a week in this lovely place and sing to you, and play with you in these beautiful grounds; then I am sure you would not be in the least afraid of this old man with a long beard.

“I have heard much about your College from my friend, Mr. Kalidas Nag, one of your former Principals, whom I met recently in Paris. He told me of the pleasant days he spent with you here.

“You are just like my boys at Shantiniketan, features, behaviour, everything. When I look into your faces, I think of them. They are not afraid of me. They drag me to their dormitories and make me take part in their plays, sing songs to them, and play parlour games with them in the long evenings.

“They can act plays beautifully, those marvellous boys, they sometimes write their own plays and act them, or act the plays written by their elders. Recently they acted a play in Calcutta, and some of my friends told me that they had not seen such acting anywhere, so perfectly natural.

“I do not want to inflict good advice on you. Why should I? You have not done any wrongs to me! I know that when I was a boy, we also used to have visits from many distinguished visitors, who gave us good advice, and told us to be good, and obedient, and to learn our lessons well. You know all that sort of thing. I do not want to repeat that. I am not a teacher really, though I have sometimes taken classes in my school, and it is not in my nature to give you good advice. I want to play with you and be your friend and companion.

“Let me describe to you what we do at Shantiniketan. We have plenty of open ground and fresh air and freedom. There are no restraints of any kind put upon the boys.

“They grow in perfect freedom and imbibe the beauties of the landscape, the sky and the seasons. Sometimes they go to swim in the tanks, and play their games when they like. They teach what they learn to their less fortunate brethren in the villages around. It is true we have no hills like yours, and we miss the great sea, but we are happy in our freedom and peace. In the long evenings we go out for walks or sit under the trees and sing songs, and we act plays in the dormitories on winter nights. Our classes are mostly held out-of doors under trees, though of course there are classrooms to be used in bad weather. The boys learn to love what is beautiful, good and true, for they imbibe these things from great Nature, who is their teacher.

“Again, I tell you that your Motherland is India, and that you have my invitation to come there whenever you like.”

According to the school magazine, Principal, F.G. Pearce then briefly thanked Dr. Tagore. He said that the great regret, especially of those who had had the experience of being for some time in the company of Dr. Tagore, among students, was that instead of staying the hoped-for week at Mahinda College, he was only able to remain for one night. However, as they knew what was the object of the poet’s visit to Ceylon, they would not grudge the shortness of his stay but be deeply grateful for his presence among them. He thought the best way to make up for it was to try to arrange, as he intended to do, for one or two of the older students to finish their education at Shantiniketan and Vishwa Bharati, and return to Mahinda College as teachers.

“You must not think that you belong exclusively to this small island; do not forget that you have unbreakable ties of language, culture and religion, with India, that ancient land! The great Mother, India, wants to clasp you to her bosom again, and I come as her messenger to claim you once more. I invite you to my Ashram at Shantiniketan. You will be welcome at any time. You will not be asked to do anything, you will be allowed to do just what you like, we shall not ask you to give our boys good advice! We shall extend our hospitality to you and make you at home among us. You may not be able to come there just now perhaps, that does not matter, but remember that if you want to come to Shantiniketan at any time, you have my invitation.”

In 1929, Jawaharlal Nehru, his wife Kamala Devi, daughter Indira and his sister Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit visited Galle. One their way to Galle, a reception was held in their honour at the Rathgama Devapathiraja College, by Sir Ernest de Silva who founded the college. At this reception, Nehru said, “Ernest is a friend of mine who was with me at Cambridge University. I am happy to see him engaged in serving the people.” At Galle, they visited Mahinda College where another reception was held in their honour.

Some of the other distinguished visitors to Galle, from India were: Dr. Annie Besant, the President of the Theosophical Society, in 1922; Sarojini Naidu, the Indian poetess, in 1922 and Harindranath Chattopadhyay, the musician and poet, in 1931.

Features

Misinterpreting President Dissanayake on National Reconciliation

President Anura Kumara Dissanayake has been investing his political capital in going to the public to explain some of the most politically sensitive and controversial issues. At a time when easier political choices are available, the president is choosing the harder path of confronting ethnic suspicion and communal fears. There are three issues in particular on which the president’s words have generated strong reactions. These are first with regard to Buddhist pilgrims going to the north of the country with nationalist motivations. Second is the controversy relating to the expansion of the Tissa Raja Maha Viharaya, a recently constructed Buddhist temple in Kankesanturai which has become a flashpoint between local Tamil residents and Sinhala nationalist groups. Third is the decision not to give the war victory a central place in the Independence Day celebrations.

Even in the opposition, when his party held only three seats in parliament, Anura Kumara Dissanayake took his role as a public educator seriously. He used to deliver lengthy, well researched and easily digestible speeches in parliament. He continues this practice as president. It can be seen that his statements are primarily meant to elevate the thinking of the people and not to win votes the easy way. The easy way to win votes whether in Sri Lanka or elsewhere in the world is to rouse nationalist and racist sentiments and ride that wave. Sri Lanka’s post independence political history shows that narrow ethnic mobilisation has often produced short term electoral gains but long term national damage.

Sections of the opposition and segments of the general public have been critical of the president for taking these positions. They have claimed that the president is taking these positions in order to obtain more Tamil votes or to appease minority communities. The same may be said in reverse of those others who take contrary positions that they seek the Sinhala votes. These political actors who thrive on nationalist mobilisation have attempted to portray the president’s statements as an abandonment of the majority community. The president’s actions need to be understood within the larger framework of national reconciliation and long term national stability.

Reconciler’s Duty

When the president referred to Buddhist pilgrims from the south going to the north, he was not speaking about pilgrims visiting long established Buddhist heritage sites such as Nagadeepa or Kandarodai. His remarks were directed at a specific and highly contentious development, the recently built Buddhist temple in Kankesanturai and those built elsewhere in the recent past in the north and east. The temple in Kankesanturai did not emerge from the religious needs of a local Buddhist community as there is none in that area. It has been constructed on land that was formerly owned and used by Tamil civilians and which came under military occupation as a high security zone. What has made the issue of the temple particularly controversial is that it was established with the support of the security forces.

The controversy has deepened because the temple authorities have sought to expand the site from approximately one acre to nearly fourteen acres on the basis that there was a historic Buddhist temple in that area up to the colonial period. However, the Tamil residents of the area fear that expansion would further displace surrounding residents and consolidate a permanent Buddhist religious presence in the present period in an area where the local population is overwhelmingly Hindu. For many Tamils in Kankesanturai, the issue is not Buddhism as a religion but the use of religion as a vehicle for territorial assertion and demographic changes in a region that bore the brunt of the war. Likewise, there are other parts of the north and east where other temples or places of worship have been established by the military personnel in their camps during their war-time occupation and questions arise regarding the future when these camps are finally closed.

There are those who have actively organised large scale pilgrimages from the south to make the Tissa temple another important religious site. These pilgrimages are framed publicly as acts of devotion but are widely perceived locally as demonstrations of dominance. Each such visit heightens tension, provokes protest by Tamil residents, and risks confrontation. For communities that experienced mass displacement, military occupation and land loss, the symbolism of a state backed religious structure on contested land with the backing of the security forces is impossible to separate from memories of war and destruction. A president committed to reconciliation cannot remain silent in the face of such provocations, however uncomfortable it may be to challenge sections of the majority community.

High-minded leadership

The controversy regarding the president’s Independence Day speech has also generated strong debate. In that speech the president did not refer to the military victory over the LTTE and also did not use the term “war heroes” to describe soldiers. For many Sinhala nationalist groups, the absence of these references was seen as an attempt to diminish the sacrifices of the armed forces. The reality is that Independence Day means very different things to different communities. In the north and east the same day is marked by protest events and mourning and as a “Black Day”, symbolising the consolidation of a state they continue to experience as excluding them and not empathizing with the full extent of their losses.

By way of contrast, the president’s objective was to ensure that Independence Day could be observed as a day that belonged to all communities in the country. It is not correct to assume that the president takes these positions in order to appease minorities or secure electoral advantage. The president is only one year into his term and does not need to take politically risky positions for short term electoral gains. Indeed, the positions he has taken involve confronting powerful nationalist political forces that can mobilise significant opposition. He risks losing majority support for his statements. This itself indicates that the motivation is not electoral calculation.

President Dissanayake has recognized that Sri Lanka’s long term political stability and economic recovery depend on building trust among communities that once peacefully coexisted and then lived through decades of war. Political leadership is ultimately tested by the willingness to say what is necessary rather than what is politically expedient. The president’s recent interventions demonstrate rare national leadership and constitute an attempt to shift public discourse away from ethnic triumphalism and toward a more inclusive conception of nationhood. Reconciliation cannot take root if national ceremonies reinforce the perception of victory for one community and defeat for another especially in an internal conflict.

BY Jehan Perera

Features

Recovery of LTTE weapons

I have read a newspaper report that the Special Task Force of Sri Lanka Police, with help of Military Intelligence, recovered three buried yet well-preserved 84mm Carl Gustaf recoilless rocket launchers used by the LTTE, in the Kudumbimalai area, Batticaloa.

These deadly weapons were used by the LTTE SEA TIGER WING to attack the Sri Lanka Navy ships and craft in 1990s. The first incident was in February 1997, off Iranativu island, in the Gulf of Mannar.

Admiral Cecil Tissera took over as Commander of the Navy on 27 January, 1997, from Admiral Mohan Samarasekara.

The fight against the LTTE was intensified from 1996 and the SLN was using her Vanguard of the Navy, Fast Attack Craft Squadron, to destroy the LTTE’s littoral fighting capabilities. Frequent confrontations against the LTTE Sea Tiger boats were reported off Mullaitivu, Point Pedro and Velvetiturai areas, where SLN units became victorious in most of these sea battles, except in a few incidents where the SLN lost Fast Attack Craft.

Carl Gustaf recoilless rocket launchers

The intelligence reports confirmed that the LTTE Sea Tigers was using new recoilless rocket launchers against aluminium-hull FACs, and they were deadly at close quarter sea battles, but the exact type of this weapon was not disclosed.

The following incident, which occurred in February 1997, helped confirm the weapon was Carl Gustaf 84 mm Recoilless gun!

DATE: 09TH FEBRUARY, 1997, morning 0600 hrs.

LOCATION: OFF IRANATHIVE.

FACs: P 460 ISRAEL BUILT, COMMANDED BY CDR MANOJ JAYESOORIYA

P 452 CDL BUILT, COMMANDED BY LCDR PM WICKRAMASINGHE (ON TEMPORARY COMMAND. PROPER OIC LCDR N HEENATIGALA)

OPERATED FROM KKS.

CONFRONTED WITH LTTE ATTACK CRAFT POWERED WITH FOUR 250 HP OUT BOARD MOTORS.

TARGET WAS DESTROYED AND ONE LTTE MEMBER WAS CAPTURED.

LEADING MARINE ENGINEERING MECHANIC OF THE FAC CAME UP TO THE BRIDGE CARRYING A PROJECTILE WHICH WAS FIRED BY THE LTTE BOAT, DURING CONFRONTATION, WHICH PENETRATED THROUGH THE FAC’s HULL, AND ENTERED THE OICs CABIN (BETWEEN THE TWO BUNKS) AND HIT THE AUXILIARY ENGINE ROOM DOOR AND HAD FALLEN DOWN WITHOUT EXPLODING. THE ENGINE ROOM DOOR WAS HEAVILY DAMAGED LOOSING THE WATER TIGHT INTEGRITY OF THE FAC.

THE PROJECTILE WAS LATER HANDED OVER TO THE NAVAL WEAPONS EXPERTS WHEN THE FACs RETURNED TO KKS. INVESTIGATIONS REVEALED THE WEAPON USED BY THE ENEMY WAS 84 mm CARL GUSTAF SHOULDER-FIRED RECOILLESS GUN AND THIS PROJECTILE WAS AN ILLUMINATER BOMB OF ONE MILLION CANDLE POWER. BUT THE ATTACKERS HAS FAILED TO REMOVE THE SAFETY PIN, THEREFORE THE BOMB WAS NOT ACTIVATED.

Sea Tigers

Carl Gustaf 84 mm recoilless gun was named after Carl Gustaf Stads Gevärsfaktori, which, initially, produced it. Sweden later developed the 84mm shoulder-fired recoilless gun by the Royal Swedish Army Materiel Administration during the second half of 1940s as a crew served man- portable infantry support gun for close range multi-role anti-armour, anti-personnel, battle field illumination, smoke screening and marking fire.

It is confirmed in Wikipedia that Carl Gustaf Recoilless shoulder-fired guns were used by the only non-state actor in the world – the LTTE – during the final Eelam War.

It is extremely important to check the batch numbers of the recently recovered three launchers to find out where they were produced and other details like how they ended up in Batticaloa, Sri Lanka?

By Admiral Ravindra C. Wijegunaratne

By Admiral Ravindra C. Wijegunaratne

WV, RWP and Bar, RSP, VSV, USP, NI (M) (Pakistan), ndc, psn, Bsc (Hons) (War Studies) (Karachi) MPhil (Madras)

Former Navy Commander and Former Chief of Defence Staff

Former Chairman, Trincomalee Petroleum Terminals Ltd

Former Managing Director Ceylon Petroleum Corporation

Former High Commissioner to Pakistan

Features

Yellow Beatz … a style similar to K-pop!

Yes, get ready to vibe with Yellow Beatz, Sri Lanka’s awesome girl group, keen to take Sri Lankan music to the world with a style similar to K-pop!

Yes, get ready to vibe with Yellow Beatz, Sri Lanka’s awesome girl group, keen to take Sri Lankan music to the world with a style similar to K-pop!

With high-energy beats and infectious hooks, these talented ladies are here to shake up the music scene.

Think bold moves, catchy hooks, and, of course, spicy versions of old Sinhala hits, and Yellow Beatz is the package you won’t want to miss!

According to a spokesman for the group, Yellow Beatz became a reality during the Covid period … when everyone was stuck at home, in lockdown.

“First we interviewed girls, online, and selected a team that blended well, as four voices, and then started rehearsals. One of the cover songs we recorded, during those early rehearsals, unexpectedly went viral on Facebook. From that moment onward, we continued doing cover songs, and we received a huge response. Through that, we were able to bring back some beautiful Sri Lankan musical creations that were being forgotten, and introduce them to the new generation.”

The team members, I am told, have strong musical skills and with proper training their goal is to become a vocal group recognised around the world.

Believe me, their goal, they say, is not only to take Sri Lanka’s name forward, in the music scene, but to bring home a Grammy Award, as well.

“We truly believe we can achieve this with the love and support of everyone in Sri Lanka.”

The year 2026 is very special for Yellow Beatz as they have received an exceptional opportunity to represent Sri Lanka at the World Championships of Performing Arts in the USA.

Under the guidance of Chris Raththara, the Director for Sri Lanka, and with the blessings of all Sri Lankans, the girls have a great hope that they can win this milestone.

“We believe this will be a moment of great value for us as Yellow Beatz, and also for all Sri Lankans, and it will be an important inspiration for the future of our country.”

Along with all the preparation for the event in the USA, they went on to say they also need to manage their performances, original song recordings, and everything related.

The year 2026 is very special for Yellow Beatz

“We have strong confidence in ourselves and in our sincere intentions, because we are a team that studies music deeply, researches within the field, and works to take the uniqueness of Sri Lankan identity to the world.”

At present, they gather at the Voices Lab Academy, twice a week, for new creations and concert rehearsals.

This project was created by Buddhika Dayarathne who is currently working as a Pop Vocal lecturer at SLTC Campus. Voice Lab Academy is also his own private music academy and Yellow Beatz was formed through that platform.

Buddhika is keen to take Sri Lankan music to the world with a style similar to K-Pop and Yellow Beatz began as a result of that vision. With that same aim, we all work together as one team.

“Although it was a little challenging for the four of us girls to work together at first, we have united for our goal and continue to work very flexibly and with dedication. Our parents and families also give their continuous blessings and support for this project,” Rameesha, Dinushi, Newansa and Risuri said.

Last year, Yellow Beatz released their first original song, ‘Ihirila’ , and with everything happening this year, they are also preparing for their first album.

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoMy experience in turning around the Merchant Bank of Sri Lanka (MBSL) – Episode 3

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoZone24x7 enters 2026 with strong momentum, reinforcing its role as an enterprise AI and automation partner

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoRemotely conducted Business Forum in Paris attracts reputed French companies

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoFour runs, a thousand dreams: How a small-town school bowled its way into the record books

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoComBank and Hayleys Mobility redefine sustainable mobility with flexible leasing solutions

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoHNB recognized among Top 10 Best Employers of 2025 at the EFC National Best Employer Awards

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoGREAT 2025–2030: Sri Lanka’s Green ambition meets a grid reality check

-

Editorial5 days ago

Editorial5 days agoAll’s not well that ends well?