Features

Downhill all the way

Review of Rajiva Wijesinha’s Representing Sri Lanka

S. Godage & Brothers, 2021, 189 pages, Rs. 750

By Uditha Devapriya

I met Rajiva Wijesinha for the first time, four years ago, at the Organisation of Professional Associations, in Colombo. At a seminar on English language learning and teaching there, he handed me a book he had published a few days earlier. Titled Endgames and Excursions, it was an account of his official travels, friendships, and associations. I remember promising to review it, reading it, and then laying it aside. It was an unforgivable omission, but one which I now feel was justified: I was simply not qualified for the task.

Since then, Dr Wijesinha has kept himself busy writing more books. This is his most recent. An account of his travels as a representative of the country, it makes for compelling reading. I am still not sure whether I am capable of reviewing another written work of his, but this is one I couldn’t resist reading through, poring over, and yes, writing on.

The book itself is different and unique. In his preface, Dr Wijesinha informs us that while he wrote much on his unofficial jaunts across the world, an account of his official travels, those undertaken between 2007 and 2014, was missing and thus needed. The result is a melange of anecdotes and analysis, a deconstruction of how we won the diplomatic war at Geneva and New York and how we lost it. For general readers as well as for students of international politics, diplomacy, even travel, it is at once instructive, enriching, and sobering.

Representing Sri Lanka begins somewhere in 2006, a year before the author was appointed as the head of the Sri Lankan Secretariat for Coordinating the Peace Process. Mindful of the allegations being thrown at us by Western powers, the Mahinda Rajapaksa administration had established the Secretariat with the express purpose of countering them. Among those machinations, one stood out in particular: a resolution sponsored by the British about which our then Ambassador in Geneva, Sarala Fernando, could do nothing. Dr Wijesinha compares this resolution to a “Sword of Damocles”, an insidious ploy through which Western interests could pressurise and punish us at any given moment.

By then Eelam War IV was in full swing. Staffed by political appointees, many of whom did little to merit their positions, the country’s Foreign Service desperately needed individuals who could respond to what Western governments and NGOs were saying about us. To that end, the British resolution needed to be countered and defeated.

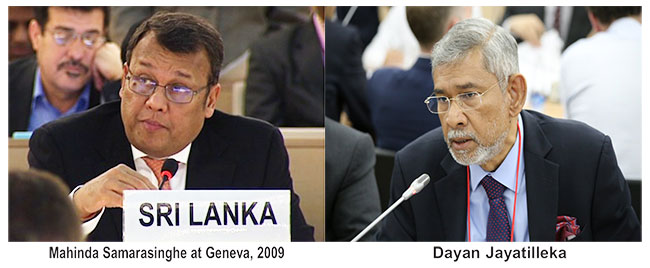

It was with that objective in view that the Rajapaksa regime appointed two individuals who were to win the diplomatic war. Dr Wijesinha recounts how these individuals did their work well, and how they were ignominiously betrayed and let down later on.

The first of them was Dr Wijesinha himself. Commencing his jaunts in Geneva, he found himself reckoning with a wide group of NGO officials, envoys, and journalists, all of them hostile to the government. To counter them, he frequently brought up the point that the government was a democratically elected outfit fighting an armed insurrection.

In his book, he carefully distinguishes between the few who understood this and the many who did not. Yet whether arguing with those hostile to us or finding common ground with those sympathetic to us, he followed the same strategy: briefing everyone on the situation in the country. This was a strategy that Colombo would abandon later on.

However ridiculous they may have been, the allegations being thrown at us required swift responses. This Dr Wijesinha ensured, in person or through his staff. Often these allegations bordered on the absurd: at one point he recalls being asked by “the astonishingly silly young lady” Nicholas Sarkozy hired as a Deputy at the French Foreign Ministry “if we had stopped using child soldiers.” Complicating matters further, NGOs continued to be given a prominent place at international forums, undermining the democratic credentials of the State. When Dr Wijesinha managed to convince officials of granting the Sri Lankan government a bigger role at these forums, he had to incur much hostility from NGOs.

Dr Wijesinha is blunt and rather pugnacious in his descriptions of some of these NGOs; at one point he even alleges that one of their officials may have been involved in intelligence work against Sri Lanka. There are times when he lets go of all decorum and resorts to the more colourful adjectives in the dictionary: remembering the local head of one NGO outfit, for instance, he calls him a “rascal.” At other times, though, he reverts to a more diplomatic demeanour: after an altercation in Geneva with a personal friend and political foe, he visits her to rekindle their old friendship. These anecdotes blend into the larger narrative, bringing out a human interest angle to what could have been a typical diplomat’s memoir.

That it desists from turning into a conventional memoir is probably the best thing about the book. To that end Dr Wijesinha summons colourful descriptions of the places and regions he visits, from runaway hotels to historical monuments.

An intrepid traveller, he makes the best of where he is, meeting old friends and reviving old friendships. He strikes a balance between official and unofficial jaunts, keeping us transfixed to both. While these never even once transcend the bigger narrative, they provide a welcome distraction from the rigours of official duties, as much to the reader as to the author himself.

As the head of the Secretariat for Coordinating the Peace Process, Dr Wijesinha had to face considerable pressure from countries that had determined to halt the war being waged in Sri Lanka. Given the odds against us, it was nothing short of a miracle that we managed to rally up a broad resistance against the 2009 UNHRC Resolution, defeating some of the most powerful states in the world. Though he refrains from claiming credit for what happened, it is clear that Dr Wijesinha was exactly where the country needed him to be.

Yet as subsequent events would testify, the triumph was not sustained. The victory we achieved in 2009, where we managed to muster a majority against the UNHCR resolution in the aftermath of the war, deteriorated to a crippling defeat three years later, when the US sponsored and passed a resolution against us. While Dr Wijesinha strikes a deeply regretful note about the train of events that led from the one to the other, he views the whole affair as inevitable. The problem, he contends, had to do with our Foreign Service.

It was a disaster waiting to unravel. From what Dr Wijesinha recounts, we can point at five reasons for why it happened. Firstly, the J. R. Jayewardene administration had bequeathed a breed of diplomats “who thought the Cubans uncivilized and the Africans unreliable.” Dr Wijesinha expresses shock and disgust when recalling some of these officials: dining with Sri Lanka’s then representative in New York, for instance, he finds it difficult to keep back his astonishment when told, sotto voce, that the Cubans are unreliable. These diplomats made it impossible to keep to a consistent foreign policy, or for that matter any policy.

Secondly, this reinforced a reluctance to respond to Western allegations about the war, a dismal no-care attitude to which Dr Wijesinha’s proactive approach became the solitary exception. Thirdly, these trends dovetailed with what he calls a “machang culture”, whereby even NGO interests who made dubious claims about the war could call their friends in high places and complain about officials questioning their credentials.

Fourthly, and perhaps more seriously, towards the end of the second Mahinda Rajapaksa government, nepotism took hold of the Foreign Service. A direct outcome of the machang culture, it ended up turning officials into mouthpieces for insidious agendas. At this point, Dr Wijesinha minces no words in explaining how two particularly shady figures in the Service, whom the reader will recognise at once, manipulated the Foreign Minister and Attorney-General. Fifthly, this brand of nepotism had the effect of fostering a culture of helplessness and timidity among the few good individuals who stayed back.

Nothing epitomised these developments better than the removal of the man responsible for the 2009 diplomatic victory. Dr Wijesinha is justifiably nostalgic in his recollections of Dayan Jayatilleka. The second of the two protagonists in his drama, Dr Jayatilleka worked with the right people to uphold a positive image of the country. That this ploy succeeded tells us just how much the reversal of such strategies after 2009 cost the country.

In that sense, the author is right in considering Dr Jayatilleka’s removal as “the silliest thing Mahinda Rajapaksa did.” In effect, it marked the beginning of the end.

Reading through the book, one feels that the heroes of these encounters have not been given their due. Dr Wijesinha tries to rescue them from anonymity, giving them credit where credit is due and noting their contributions. Indeed, he is only too right in his view that while Sri Lanka’s diplomatic war has been praised and written about internationally, it has not got the attention it deserves locally. To be sure, the war ended somewhere in Nandikadal. But far from allowing it to rest it there, the world tried again and again to ensure that Sri Lanka’s government would be punished for ending it in defiance of their strictures. It was here that the diplomatic war became crucial, a point not many have appreciated.

Writing as a diplomat, an ex-government MP, and a liberal ideologue, Dr Wijesinha brings all these narratives together, telling us where we went wrong in the hopes of showing us what we can improve on. A liberal of the old school, he is rather incensed about how his political convictions have been co-opted by certain people in pursuit of agendas detrimental to the country’s interests. Here he underscores his dissatisfaction about how, in the Global South, liberalism has become a front for “doctrinaire neoliberalism.”

Towards the end of the book he devotes a chapter to this theme, titled “The death of liberal Sri Lanka.” It’s not a little tongue-in-cheek: he is referring not to what liberals in the country dread, namely the rise of their bête noire, the Rajapaksas, but rather the death of liberalism among liberal ranks. Dr Wijesinha is at his bitterest here, when castigating those who have turned Sri Lanka’s liberal movement into a reflection of what it used to be. While striking a personal note, he suggests that this has had and continues to have a bearing on the island’s image internationally, a point that needs to be addressed at once.

Sri Lankans can be justifiably proud of being heirs to a diplomatic tradition that won us a place in the world. Yet this is a tradition in need of those who can pass it on to the next few generations. Without those who can take it forward, the country runs the risk of losing its voice in international forums. To this end, Rajiva Wijesinha’s book highlights where we went wrong, in the hope of building up “a coherent and productive foreign policy.” Such a policy has become the need of the hour. We can no longer afford to ignore it.

The writer can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com

Features

Challenges faced by the media in South Asia in fostering regionalism

SAARC or the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation has been declared ‘dead’ by some sections in South Asia and the idea seems to be catching on. Over the years the evidence seems to have been building that this is so, but a matter that requires thorough probing is whether the media in South Asia, given the vital part it could play in fostering regional amity, has had a role too in bringing about SAARC’s apparent demise.

SAARC or the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation has been declared ‘dead’ by some sections in South Asia and the idea seems to be catching on. Over the years the evidence seems to have been building that this is so, but a matter that requires thorough probing is whether the media in South Asia, given the vital part it could play in fostering regional amity, has had a role too in bringing about SAARC’s apparent demise.

That South Asian governments have had a hand in the ‘SAARC debacle’ is plain to see. For example, it is beyond doubt that the India-Pakistan rivalry has invariably got in the way, particularly over the past 15 years or thereabouts, of the Indian and Pakistani governments sitting at the negotiating table and in a spirit of reconciliation resolving the vexatious issues growing out of the SAARC exercise. The inaction had a paralyzing effect on the organization.

Unfortunately the rest of South Asian governments too have not seen it to be in the collective interest of the region to explore ways of jump-starting the SAARC process and sustaining it. That is, a lack of statesmanship on the part of the SAARC Eight is clearly in evidence. Narrow national interests have been allowed to hijack and derail the cooperative process that ought to be at the heart of the SAARC initiative.

However, a dimension that has hitherto gone comparatively unaddressed is the largely negative role sections of the media in the SAARC region could play in debilitating regional cooperation and amity. We had some thought-provoking ‘takes’ on this question recently from Roman Gautam, the editor of ‘Himal Southasian’.

Gautam was delivering the third of talks on February 2nd in the RCSS Strategic Dialogue Series under the aegis of the Regional Centre for Strategic Studies, Colombo, at the latter’s conference hall. The forum was ably presided over by RCSS Executive Director and Ambassador (Retd.) Ravinatha Aryasinha who, among other things, ensured lively participation on the part of the attendees at the Q&A which followed the main presentation. The talk was titled, ‘Where does the media stand in connecting (or dividing) Southasia?’.

Gautam singled out those sections of the Indian media that are tamely subservient to Indian governments, including those that are professedly independent, for the glaring lack of, among other things, regionalism or collective amity within South Asia. These sections of the media, it was pointed out, pander easily to the narratives framed by the Indian centre on developments in the region and fall easy prey, as it were, to the nationalist forces that are supportive of the latter. Consequently, divisive forces within the region receive a boost which is hugely detrimental to regional cooperation.

Two cases in point, Gautam pointed out, were the recent political upheavals in Nepal and Bangladesh. In each of these cases stray opinions favorable to India voiced by a few participants in the relevant protests were clung on to by sections of the Indian media covering these trouble spots. In the case of Nepal, to consider one example, a young protester’s single comment to the effect that Nepal too needed a firm leader like Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi was seized upon by the Indian media and fed to audiences at home in a sensational, exaggerated fashion. No effort was made by the Indian media to canvass more opinions on this matter or to extensively research the issue.

In the case of Bangladesh, widely held rumours that the Hindus in the country were being hunted and killed, pogrom fashion, and that the crisis was all about this was propagated by the relevant sections of the Indian media. This was a clear pandering to religious extremist sentiment in India. Once again, essentially hearsay stories were given prominence with hardly any effort at understanding what the crisis was really all about. There is no doubt that anti-Muslim sentiment in India would have been further fueled.

Gautam was of the view that, in the main, it is fear of victimization of the relevant sections of the media by the Indian centre and anxiety over financial reprisals and like punitive measures by the latter that prompted the media to frame their narratives in these terms. It is important to keep in mind these ‘structures’ within which the Indian media works, we were told. The issue in other words, is a question of the media completely subjugating themselves to the ruling powers.

Basically, the need for financial survival on the part of the Indian media, it was pointed out, prompted it to subscribe to the prejudices and partialities of the Indian centre. A failure to abide by the official line could spell financial ruin for the media.

A principal question that occurred to this columnist was whether the ‘Indian media’ referred to by Gautam referred to the totality of the Indian media or whether he had in mind some divisive, chauvinistic and narrow-based elements within it. If the latter is the case it would not be fair to generalize one’s comments to cover the entirety of the Indian media. Nevertheless, it is a matter for further research.

However, an overall point made by the speaker that as a result of the above referred to negative media practices South Asian regionalism has suffered badly needs to be taken. Certainly, as matters stand currently, there is a very real information gap about South Asian realities among South Asian publics and harmful media practices account considerably for such ignorance which gets in the way of South Asian cooperation and amity.

Moreover, divisive, chauvinistic media are widespread and active in South Asia. Sri Lanka has a fair share of this species of media and the latter are not doing the country any good, leave alone the region. All in all, the democratic spirit has gone well into decline all over the region.

The above is a huge problem that needs to be managed reflectively by democratic rulers and their allied publics in South Asia and the region’s more enlightened media could play a constructive role in taking up this challenge. The latter need to take the initiative to come together and deliberate on the questions at hand. To succeed in such efforts they do not need the backing of governments. What is of paramount importance is the vision and grit to go the extra mile.

Features

When the Wetland spoke after dusk

By Ifham Nizam

As the sun softened over Colombo and the city’s familiar noise began to loosen its grip, the Beddagana Wetland Park prepared for its quieter hour — the hour when wetlands speak in their own language.

World Wetlands Day was marked a little early this year, but time felt irrelevant at Beddagana. Nature lovers, students, scientists and seekers gathered not for a ceremony, but for listening. Partnering with Park authorities, Dilmah Conservation opened the wetland as a living classroom, inviting more than a 100 participants to step gently into an ecosystem that survives — and protects — a capital city.

Wetlands, it became clear, are not places of stillness. They are places of conversation.

Beyond the surface

In daylight, Beddagana appears serene — open water stitched with reeds, dragonflies hovering above green mirrors.

Yet beneath the surface lies an intricate architecture of life. Wetlands are not defined by water alone, but by relationships: fungi breaking down matter, insects pollinating and feeding, amphibians calling across seasons, birds nesting and mammals moving quietly between shadows.

Participants learned this not through lectures alone, but through touch, sound and careful observation. Simple water testing kits revealed the chemistry of urban survival. Camera traps hinted at lives lived mostly unseen.

Demonstrations of mist netting and cage trapping unfolded with care, revealing how science approaches nature not as an intruder, but as a listener.

Again and again, the lesson returned: nothing here exists in isolation.

Learning to listen

Perhaps the most profound discovery of the day was sound.

Wetlands speak constantly, but human ears are rarely tuned to their frequency. Researchers guided participants through the wetland’s soundscape — teaching them to recognise the rhythms of frogs, the punctuation of insects, the layered calls of birds settling for night.

Then came the inaudible made audible. Bat detectors translated ultrasonic echolocation into sound, turning invisible flight into pulses and clicks. Faces lit up with surprise. The air, once assumed empty, was suddenly full.

It was a moment of humility — proof that much of nature’s story unfolds beyond human perception.

Sethil on camera trapping

The city’s quiet protectors

Environmental researcher Narmadha Dangampola offered an image that lingered long after her words ended. Wetlands, she said, are like kidneys.

“They filter, cleanse and regulate,” she explained. “They protect the body of the city.”

Her analogy felt especially fitting at Beddagana, where concrete edges meet wild water.

She shared a rare confirmation: the Collared Scops Owl, unseen here for eight years, has returned — a fragile signal that when habitats are protected, life remembers the way back.

Small lives, large meanings

Professor Shaminda Fernando turned attention to creatures rarely celebrated. Small mammals — shy, fast, easily overlooked — are among the wetland’s most honest messengers.

Using Sherman traps, he demonstrated how scientists read these animals for clues: changes in numbers, movements, health.

In fragmented urban landscapes, small mammals speak early, he said. They warn before silence arrives.

Their presence, he reminded participants, is not incidental. It is evidence of balance.

Narmadha on water testing pH level

Wings in the dark

As twilight thickened, Dr. Tharaka Kusuminda introduced mist netting — fine, almost invisible nets used in bat research.

He spoke firmly about ethics and care, reminding all present that knowledge must never come at the cost of harm.

Bats, he said, are guardians of the night: pollinators, seed dispersers, controllers of insects. Misunderstood, often feared, yet indispensable.

“Handle them wrongly,” he cautioned, “and we lose more than data. We lose trust — between science and life.”

The missing voice

One of the evening’s quiet revelations came from Sanoj Wijayasekara, who spoke not of what is known, but of what is absent.

In other parts of the region — in India and beyond — researchers have recorded female frogs calling during reproduction. In Sri Lanka, no such call has yet been documented.

The silence, he suggested, may not be biological. It may be human.

“Perhaps we have not listened long enough,” he reflected.

The wetland, suddenly, felt like an unfinished manuscript — its pages alive with sound, waiting for patience rather than haste.

The overlooked brilliance of moths

Night drew moths into the light, and with them, a lesson from Nuwan Chathuranga. Moths, he said, are underestimated archivists of environmental change. Their diversity reveals air quality, plant health, climate shifts.

As wings brushed the darkness, it became clear that beauty often arrives quietly, without invitation.

Sanoj on female frogs

Coexisting with the wild

Ashan Thudugala spoke of coexistence — a word often used, rarely practiced. Living alongside wildlife, he said, begins with understanding, not fear.

From there, Sethil Muhandiram widened the lens, speaking of Sri Lanka’s apex predator. Leopards, identified by their unique rosette patterns, are studied not to dominate, but to understand.

Science, he showed, is an act of respect.

Even in a wetland without leopards, the message held: knowledge is how coexistence survives.

When night takes over

Then came the walk: As the city dimmed, Beddagana brightened. Fireflies stitched light into darkness. Frogs called across water. Fish moved beneath reflections. Insects swarmed gently, insistently. Camera traps blinked. Acoustic monitors listened patiently.

Those walking felt it — the sense that the wetland was no longer being observed, but revealed.

For many, it was the first time nature did not feel distant.

Faunal diversity at the Beddagana Wetland Park

A global distinction, a local duty

Beddagana stands at the heart of a larger truth. Because of this wetland and the wider network around it, Colombo is the first capital city in the world recognised as a Ramsar Wetland City.

It is an honour that carries obligation. Urban wetlands are fragile. They disappear quietly. Their loss is often noticed only when floods arrive, water turns toxic, or silence settles where sound once lived.

Commitment in action

For Dilmah Conservation, this night was not symbolic.

Speaking on behalf of the organisation, Rishan Sampath said conservation must move beyond intention into experience.

“People protect what they understand,” he said. “And they understand what they experience.”

The Beddagana initiative, he noted, is part of a larger effort to place science, education and community at the centre of conservation.

Listening forward

As participants left — students from Colombo, Moratuwa and Sabaragamuwa universities, school environmental groups, citizens newly attentive — the wetland remained.

It filtered water. It cooled air. It held life.

World Wetlands Day passed quietly. But at Beddagana, something remained louder than celebration — a reminder that in the heart of the city, nature is still speaking.

The question is no longer whether wetlands matter.

It is whether we are finally listening.

Features

Cuteefly … for your Valentine

Valentine’s Day is all about spreading love and appreciation, and it is a mega scene on 14th February.

Valentine’s Day is all about spreading love and appreciation, and it is a mega scene on 14th February.

People usually shower their loved ones with gifts, flowers (especially roses), and sweet treats.

Couples often plan romantic dinners or getaways, while singles might treat themselves to self-care or hang out with friends.

It’s a day to express feelings, share love, and make memories, and that’s exactly what Indunil Kaushalya Dissanayaka, of Cuteefly fame, is working on.

She has come up with a novel way of making that special someone extra special on Valentine’s Day.

Indunil is known for her scented and beautifully turned out candles, under the brand name Cuteefly, and we highlighted her creativeness in The Island of 27th November, 2025.

She is now working enthusiastically on her Valentine’s Day candles and has already come up with various designs.

“What I’ve turned out I’m certain will give lots of happiness to the receiver,” said Indunil, with confidence.

In addition to her own designs, she says she can make beautiful candles, the way the customer wants it done and according to their budget, as well.

Customers can also add anything they want to the existing candles, created by Indunil, and make them into gift packs.

Customers can also add anything they want to the existing candles, created by Indunil, and make them into gift packs.

Another special feature of Cuteefly is that you can get them to deliver the gifts … and surprise that special someone on Valentine’s Day.

Indunil was originally doing the usual 9 to 5 job but found it kind of boring, and then decided to venture into a scene that caught her interest, and brought out her hidden talent … candle making

And her scented candles, under the brand ‘Cuteefly,’ are already scorching hot, not only locally, but abroad, as well, in countries like Canada, Dubai, Sweden and Japan.

“I give top priority to customer satisfaction and so I do my creative work with great care, without any shortcomings, to ensure that my customers have nothing to complain about.”

“I give top priority to customer satisfaction and so I do my creative work with great care, without any shortcomings, to ensure that my customers have nothing to complain about.”

Indunil creates candles for any occasion – weddings, get-togethers, for mental concentration, to calm the mind, home decorations, as gifts, for various religious ceremonies, etc.

In addition to her candle business, Indunil is also a singer, teacher, fashion designer, and councellor but due to the heavy workload, connected with her candle business, she says she can hardly find any time to devote to her other talents.

Indunil could be contacted on 077 8506066, Facebook page – Cuteefly, Tiktok– Cuteefly_tik, and Instagram – Cuteeflyofficial.

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoSri Lanka, the Stars,and statesmen

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoHayleys Mobility ushering in a new era of premium sustainable mobility

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoSLIM-Kantar People’s Awards 2026 to recognise Sri Lanka’s most trusted brands and personalities

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoAdvice Lab unveils new 13,000+ sqft office, marking major expansion in financial services BPO to Australia

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoArpico NextGen Mattress gains recognition for innovation

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoAltair issues over 100+ title deeds post ownership change

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoSri Lanka opens first country pavilion at London exhibition

-

Editorial5 days ago

Editorial5 days agoGovt. provoking TUs