Features

Diversifying in new directions – hospitality plantations, broking and health care

(Excerpted from the Merrill J Fernando autobiography)

Sometime in 2003, together with Dilhan and his family, I holidayed in Bali. Indonesia, at Bali Villas, an exclusive hospitality complex. We rented two units which came with a highly-personalized service, including maids and a chef for each villa. We also had our own swimming pools and a common spa facility. Outside the complex there were cafes, restaurants, and little eating houses, offering dazzling arrays of food, which made eating out a daily adventure.

On the morning of the second day, a very tall gentleman walked in to my villa and introduced himself: “Good morning, Mr. Dilmah, I am an Aussie and the owner of this hotel.” Over a cup of tea, he told me his story. He had first visited Sri Lanka looking for both a location and a partner to launch this special hospitality concept he had in mind. Whilst he had been happy with the opportunities, he had not been able to find a suitable partner, nor had he been very comfortable with the political climate. Abandoning Sri Lanka for those reasons, eventually be had located this special project in Bali.

After an interesting conversation with me, he called his CEO, Chris Green, an Englishman, and told him to give us anything we wanted and Chris offered us a 60% discount on all the spa treatments. In the course of our friendly discussion with Chris which followed, I told him that I was interested in setting up a similar project in Sri Lanka and asked for his advice.

One week later Chris was in Sri Lanka and Malik was taking him around, visiting potential locations in the plantation regions. The tourist industry has always attracted me, in view of the tremendous potential that Sri Lanka possesses and the fact that it is an industry that Sri Lanka can own totally. The raw material is the composites of our unparalleled natural beauty, the easily accessible game parks, the cultural and historical heritage seen in our many ancient cities like Polonnaruwa, Anuradhapura, and Sigiriya, and the natural friendliness and spontaneous, welcoming hospitality of our people. These charming inborn attributes cannot be supplanted by imports!

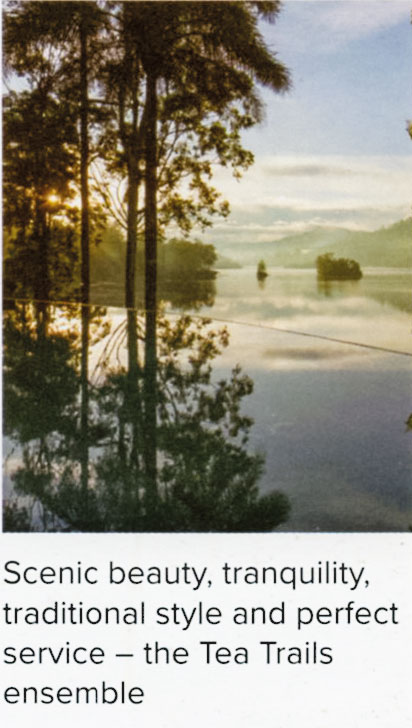

Ceylon Tea Trails

Our upcountry plantation areas are amongst the most scenic in the country, with the emerald green cover of tea carpeting an undulating landscape, broken up by spectacular rock escarpments and mountains blanketed by montane forest, heavily-wooded ravines in the valleys, and the whole crisscrossed by tumbling streams and cascading waterfalls.

There are also the historic plantation bungalows, rambling and comfortable, often somewhat neglected but set in large gardens and, invariably, panoramically sited. The British who first built them had, collectively, an unerring instinct for commanding locations, obviously conditioned by the ‘monarch of all I survey’ worldview of the Western coloniser.

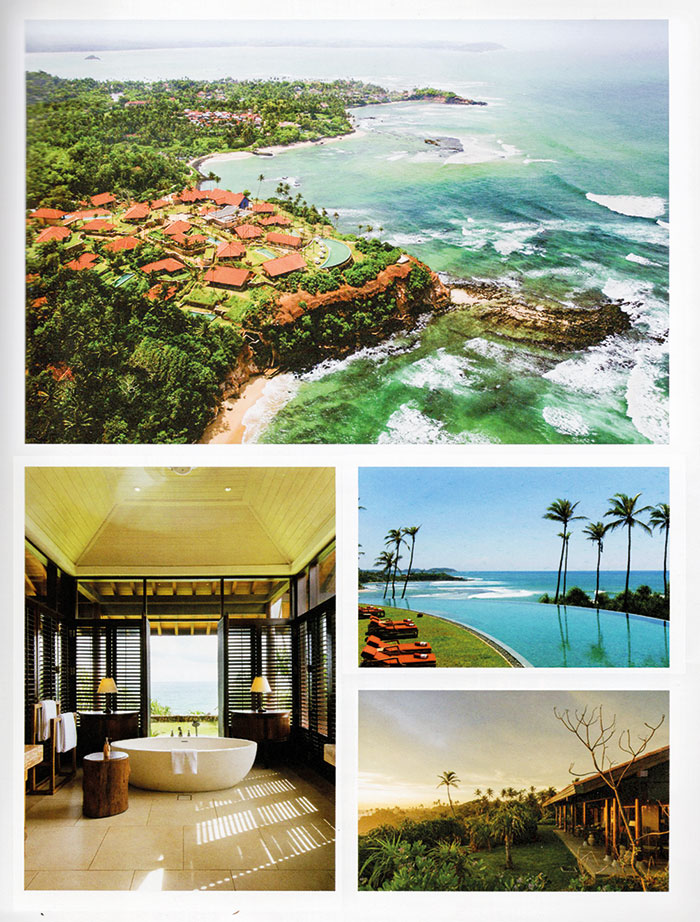

The Cape — A peerless location View from the pool — all the way to the South Pole Tranquility at dusk Old fashioned comfort in a modern setting

Following the preliminary tour with Chris, Malik engaged Miguel, a young Spaniard, who toured the plantation regions on a motorcycle and identified four bungalows with the best combination of scenery, attractive bungalow configuration, and accessibility: the Tientsin, Norwood, Summerville, and Castlereagh bungalows, all located in close proximity to each other in the Bogawanthalawa-Norwood area, were finally selected for the project.

The proximity of the picturesque Castlereagh Reservoir, nestled in the basin created by the surrounding tea-covered hills, was one of the key selling points. Later, Dunkeld bungalow, sited on the Western banks of the reservoir and located on our own estate, was restored and added to the list, when the demand for accommodation rapidly overtook capacity.

A South African interior designer was selected to reconfigure and refurbish all the bungalows. This was a delicately-managed operation, as the prime consideration was to maintain the original, old world charm of the bungalows, whilst unobtrusively introducing all the modern amenities and conveniences expected by a discerning clientele, accustomed to and prepared to pay for luxurious but unique hostelry in exclusive locations. The new had to merge seamlessly with the old, as if the offering in its entirety had been there always, handed down intact across generations by the original British owners.

The features of comfort and attraction needed to be tangible, quantifiable, and visible, while the designer’s hand remained invisible. There were no invoices submitted to the guest on departure. The customer was made to feel that he/she was holidaying in the home of a wealthy, generous, and caring friend. It was a personalized service where guests discussed dining choices for each meal with an own chef, whilst the in-house butlers’ service was at hand, at any time of the day or night, to attend to every guest need or fancy. What was on offer was a fully-inclusive concept, which anticipated and provided everything that the guest needed and desired.

Thus, with the opening of the first bungalow, Castlereagh, in June 2005, ‘Ceylon Tea Trails’ was born and, simultaneously, Malik came in to his own as an entrepreneur. Tea Trails projected the now somewhat-hackneyed boutique hotel concept into a new dimension, previously unknown to Sri Lanka. The bungalows were between two to 15 kilometres apart and guests could walk or cycle between them, and be served meals in any one of them, as if they had visited the house of a close friend. Each bungalow had four to five bedrooms and suites and a total of 27 rooms, in locations in the tea-covered hills encircling the Castlereagh Reservoir.

Many of the vegetables, herbs, and spices featured in the wide-ranging and exquisite cuisine on offer at the bungalows are grown organically in the bungalow gardens themselves. The preparation is personally handled by experienced chefs with international training.

Tea Trails soon became a high-demand holiday destination, fully booked most of the time and I frequently had great difficulty in securing a room when I wanted one. Most bookings were repeats and made a year ahead! Finally, Malik developed a nice little cottage on Dunkeld, designated as the ‘Owner’s Cottage,’ for my personal use, supposedly at my will and pleasure.

Once it was done I asked him to hand the keys over to me, but I was not very surprised when Malik apologetically responded that I would have to be little patient as it had been booked till the end of August that year! Though it has been over two years since it was completed, I have been able to occupy it with friends only once.

On account of its exclusivity, exceptional quality of service and cuisine, and guests’ recommendations, Tea Trails was invited to join the prestigious Paris-based Relais & Chateaux Association, known for its uncompromisingly rigid admission standards. Since the 65 years of its founding in France, it has permitted only 580 landmark hotels and restaurants worldwide to enter its elite membership.

Since then the two other resorts in our group which followed, Tea Trails, Cape Weligama in Weligama and Wild Coast Tented Lodge, deeper south in Yala, have been admitted to Relais & Chateaux to date the only three members in Sri Lanka.

Cape Weligama

A few years ago, Malik persuaded me to buy a beautiful hilltop property near the beach in Weligama, overlooking the Indian Ocean east of Galle. My original intention was to resell it to a hotel developer, but Malik had other ideas and convinced me that the location was ideal for an exclusive, boutique-type hotel. He hired a well-known architect, Lek Bunnag from Thailand, who produced an exceptional design.

Along with Malik I visited Bangkok to review the plans and was very impressed by them. The construction then commenced and on completion, much to my serious displeasure, the final cost had far exceeded the initial budget.

Malik’s explanation was that this was the first hotel we built from ground-up and that it was also a learning experience for us! Further, in the process of construction, many new features had to be introduced to complement the degree of exclusivity and uniqueness that we were striving for. It opened in 2014 with 39 suites and villas, the latter starting at around 130 square metres in extent.

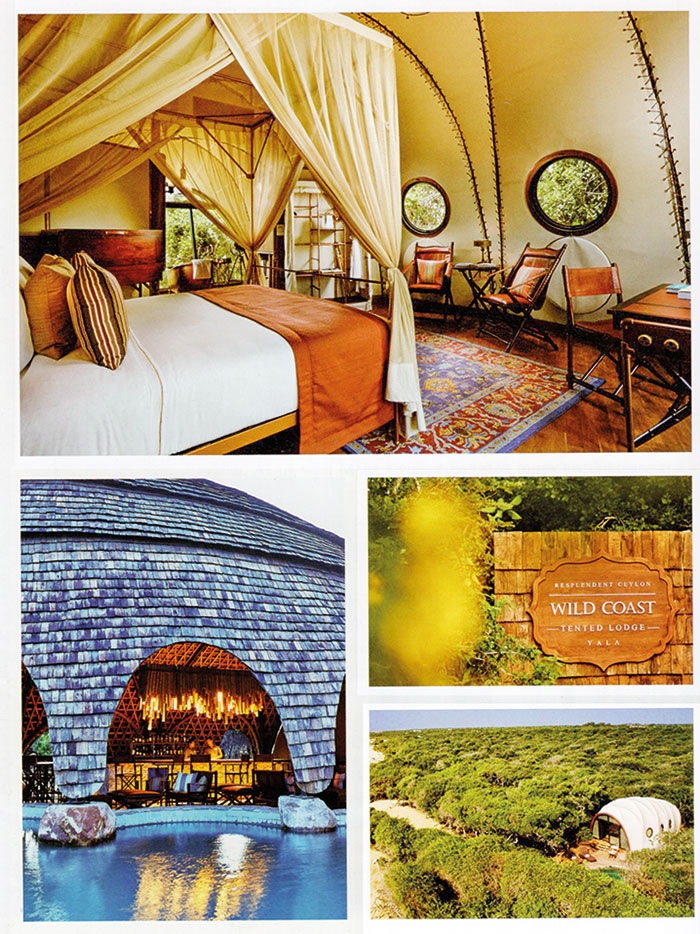

Wild Coast Lodge

With two exclusive and successful tourist destinations in our portfolio, and a little more experience in the hospitality trade under our belts, we decided to expand further in that direction and commenced work on a seven-acre, heavily-wooded site, near the Yala National Park. The land, between the beach and the jungle and comprising a contiguous segment of the real jungle, lent itself ideally to the concept we had in mind for a tented, but luxurious resort.

It is an arresting fusion of two extremes, the wildness and the potential danger of the proximal animal inhabited scrub forest, as a counterpoint to the understated indulgence of every modern comfort and convenience within. The bamboo and tented resort blended seamlessly with the surrounding forest and opened for business in 2017. It has since has won several global awards, including a UNESCO award for uniqueness of design.

Resplendent Ceylon

With these three destinations, Malik has very successfully captured the contrasting aspects of the beauty of different parts of our country, and the scenic diversity it has to offer the traveler. “Resplendent Ceylon,” as he calls this varied collection the gentle, quaint charm of our verdant plantation country, with its cool climate and orderly tea cultivation, the warm, balmy beach land of the south, and the harsh, arid beauty of the south east epitomizes the multi-faceted, natural splendour of our country. The only commonality between these destinations, with such contrasting features of attractiveness, is the matchless service they offer. Given these attributes, it is fair to say that Resplendent Ceylon is the pioneering small luxury hotel brand in Sri Lanka.

Acquisition of Forbes and Walker and Kahawatte Plantations

Elsewhere in this writing I have several times referred to my resolve to eventually become independent of external assistance for critical aspects of my business operation. In this age of enterprise complexity, admittedly, it is difficult for any operation, however efficient it may be, to be totally self-sufficient. Independent providers of ancillary services and products do play an important part in any large business operation. Generally, obtaining the services of independent contractors to complement the less-crucial aspects of your operation makes sound commercial sense.

However, in regard to my tea export business, the mainstay of my group enterprise, I was determined that I would become totally self-reliant, with direct ownership and control of the value chain, ‘from-bush-to-cup’ as it were. It was that intent which earlier led to my investing in Printcare. I did not put a label on my purpose, but business management experts identify it as the principle of ‘vertical integration’.

I decided that the first step in the above direction would be to acquire control of a tea broking company. Broking has been an important corollary activity of the plantation industry, growing from a purely marketing service in its infancy in the last quarter of the 19th century, to its present multi-faceted role as provider of warehousing, finance, technical advisory, and other related services.

Sometime in early 2000 I became aware that the owners of Forbes Ceylon Limited (FCL), VANIK Incorporated a now largely-inactive private investment bank were seriously considering the sale of Forbes & Walker (F&W), including its produce broking arm, Forbes Tea Brokers, a very reliable and well-established broking firm with a long history. As a tea buyer and exporter for over five decades up to that time, I was very familiar with the company and, over the years, had got to know all its key personnel from the early 1950s onwards.

However, one condition attached by VANIK to the sale of Forbes was that Forbes Plantations, through which it owned Kahawatte Plantations Plc, a Regional Plantation Company, should also be disposed of at the same time. The intention of VANIK was to exit from the tea industry altogether. The purchase of Kahawatte Plantations, then owned by FCL, had to be part of the transaction. One could not happen without the other.

Whilst I was discussing the possible sale of Forbes Brokers with VANIK, the latter were in negotiation with another party, Central Highfields Ceylon (Pvt) Ltd. (CHFC) incorporated in the UK, with its Sri Lankan interests represented by Nimal Silva, a former planter, for the sale of Kahawatte Plantations. An agreement had been signed between VANIK, CHFC, and FCL, with CHFC paying an advance of Rs. 100 million against an agreed price of Rs. 200 million, for the purchase of a majority shareholding of Kahawatte, through Forbes Plantations.

Since CHFC was unable to deliver the balance Rs. 100 million on the due date, it agreed to VANIK borrowing the sum from my company. I agreed to the proposal, because I wanted to assist CHFC in its purchase of Kahawatte, thus ensuring that I would be able to purchase Forbes Brokers, thereby meeting VANIK’s condition of an exit from the tea industry altogether. As security against the loan, VANIK furnished my company with a primary mortgage over the Kahawatte shares held by Forbes Plantations.

Luxury inside a tent The forest outside and the indulgence within — a matchless union. Unique design

It had not been my original intention to buy the plantation company as, at that time, my company already had sizeable holdings in both Elpitiya and Talawakelle Plantations. Therefore, a produce broking company was the only missing link in the vertical integration value chain.

I gave CHFC more than one extension on the deadline for the settlement of the advance. In fact, even after I had served VANIK with notice to transfer the Kahawatte shareholding in lieu of settlement of the loan. I gave additional time to CHFC to settle the issue. However, it was unable to secure funding and by end of 2000, both Forbes & Walker and Kahawatte Plantations had become part of the MJF Group of Companies.

The main reason for my decision to exercise my right to the Kahawatte shareholding, was that the uncertainty surrounding the ownership transfer was soon reflected in management inadequacies,which were visibly affecting the company’s performance. Further delays in the finalization of the transaction would only have accelerated its decline.

When I acquired Kahawatte, it was in dire financial straits, with large accumulated losses and substantial liabilities, a significant proportion of the latter represented by unpaid statutory dues. Those

were settled soon after the acquisition. Subsequently, a comprehensive factory rehabilitation, in parallel with a product quality policy drive, resulted in the company achieving the highest annual net sale average for in the Regional Plantation Company sector.

It has maintained this position for several years. Apart from the capital intensive consolidation of core crops, involving extensive replanting of both tea and rubber, we also launched a major crop diversification initiative, cultivating Ceylon Cinnamon in the low-country sector. Presently, Kahawatte has over 200 Ha in mature cinnamon, making it the largest single owner of cinnamon in the country.

Since its acquisition, the investment in shares and the value of corporate guarantees extended to Kahawatte by MJF Holdings and its subsidiaries together exceed Rs. 3 billion. As for Forbes & Walker, it was my firm belief that as a broker, F&W should remain independent, despite being part of the main group. That could be achieved only if the management also had a stake in the company, with the company itself being operated as a Joint Venture. Consequently, I caused a management trust to be created, which held 30% of the F&W shareholding on behalf of the management of the broking company. It proved to be a sound principle and has continued to operate efficiently to the present day.

The health sector

My friend, the late Lawrence Tudawe, who built my Maligawatte office and packing complex, had, at some point in time, purchased Durdans Hospital. It had been founded in 1939 and in the colonial period, was the primary military hospital in then Ceylon, mostly serving the British Armed Forces then stationed in the country. In 1945 it was acquired by a group of doctors and managed as Ceylon Hospitals Limited, before being bought by the Tudawe family.

The younger Tudawes , Ajit, Rohan, and Upul have since developed it to its present position as one of the finest private healthcare centres in the country. A few years ago, I was persuaded by the Tudawe family to invest in the company and I acquired a reasonable shareholding in Ceylon Hospitals, which owns and operates Durdans Hospital. Subsequently I made a further investment in the more modern entity, Durdans Medical and Surgical Hospitals (Pvt) Ltd. I consider it a very useful investment, not only on account of the financial returns but also because of the excellent healthcare service it provides the public, which also includes the employees of my group of companies.

Features

Australia’s social media ban: A sledgehammer approach to a scalpel problem

When governments panic, they legislate. When they legislate in panic, they create monsters. Australia’s world-first ban on social media for under-16s, which came into force on 10 December, 2025, is precisely such a monster, a clumsy, authoritarian response to a legitimate problem that threatens to do more harm than good.

When governments panic, they legislate. When they legislate in panic, they create monsters. Australia’s world-first ban on social media for under-16s, which came into force on 10 December, 2025, is precisely such a monster, a clumsy, authoritarian response to a legitimate problem that threatens to do more harm than good.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese hailed it as a “proud day” for Australian families. One wonders what there is to be proud about when a liberal democracy resorts to blanket censorship, violates children’s fundamental rights, and outsources enforcement to the very tech giants it claims to be taming. This is not protection; it is political theatre masquerading as policy.

The Seduction of Simplicity

The ban’s appeal is obvious. Social media platforms have become toxic playgrounds where children are subjected to cyberbullying, addictive algorithms, and content that can genuinely harm their mental health. The statistics are damning: 40% of Australian teens have experienced cyberbullying, youth self-harm hospital admissions rose 47% between 2012 and 2022, and depression rates have skyrocketed in tandem with smartphone adoption. These are real problems demanding real solutions.

But here’s where Australia has gone catastrophically wrong: it has conflated correlation with causation and chosen punishment over education, restriction over reform, and authoritarian control over empowerment. The ban assumes that removing children from social media will magically solve mental health crises, as if these platforms emerged in a vacuum rather than as symptoms of deeper societal failures, inadequate mental health services, overworked parents, underfunded schools, and a culture that has outsourced child-rearing to screens.

Dr. Naomi Lott of the University of Reading hit the nail on the head when she argued that the ban unfairly burdens youth for tech firms’ failures in content moderation and algorithm design. Why should children pay the price for corporate malfeasance? This is akin to banning teenagers from roads because car manufacturers built unsafe vehicles, rather than holding those manufacturers accountable.

The Enforcement Farce

The practical implementation of this ban reads like dystopian satire. Platforms must take “reasonable steps” to prevent access, a phrase so vague it could mean anything or nothing. The age verification methods being deployed include AI-driven facial recognition, behavioural analysis, government ID scans, and something called “AgeKeys.” Each comes with its own Pandora’s box of problems.

Facial recognition technology has well-documented biases against ethnic minorities. Behavioural analysis can be easily gamed by tech-savvy teenagers. ID scans create massive privacy risks in a country that has suffered repeated data breaches. And zero-knowledge proof, while theoretically elegant, require a level of technical sophistication that makes them impractical for mass adoption.

Already, teenagers are bragging online about circumventing the restrictions, prompting Albanese’s impotent rebuke. What did he expect? That Australian youth would simply accept digital exile? The history of prohibition, from alcohol to file-sharing, teaches us that determined users will always find workarounds. The ban doesn’t eliminate risk; it merely drives it underground where it becomes harder to monitor and address.

Even more absurdly, platforms like YouTube have expressed doubts about enforcement, and Opposition Leader Sussan Ley has declared she has “no confidence” in the ban’s efficacy. When your own political opposition and the companies tasked with implementing your policy both say it won’t work, perhaps that’s a sign you should reconsider.

The Rights We’re Trading Away

The legal challenges now percolating through Australia’s High Court get to the heart of what’s really at stake here. The Digital Freedom Project, led by teenagers Noah Jones and Macy Neyland, argues that the ban violates the implied constitutional freedom of political communication. They’re right. Social media platforms, for all their flaws, have become essential venues for democratic discourse. By age 16, many young Australians are politically aware, engaged in climate activism, and participating in public debates. This ban silences them.

The government’s response, that child welfare trumps absolute freedom, sounds reasonable until you examine it closely. Child welfare is being invoked as a rhetorical trump card to justify what is essentially state paternalism. The government isn’t protecting children from objective harm; it’s making a value judgment about what information they should be allowed to access and what communities they should be permitted to join. That’s thought control, not child protection.

Moreover, the ban creates a two-tiered system of rights. Those over 16 can access platforms; those under cannot, regardless of maturity, need, or circumstance. A 15-year-old seeking LGBTQ+ support groups, mental health resources, or information about escaping domestic abuse is now cut off from potentially life-saving communities. A 15-year-old living in rural Australia, isolated from peers, loses a vital social lifeline. The ban is blunt force trauma applied to a problem requiring surgical precision.

The Privacy Nightmare

Let’s talk about the elephant in the digital room: data security. Australia’s track record here is abysmal. The country has experienced multiple high-profile data breaches, and now it’s mandating that platforms collect biometric data, government IDs, and behavioural information from millions of users, including adults who will need to verify their age to distinguish themselves from banned minors.

The legislation claims to mandate “data minimisation” and promises that information collected solely for age verification will be destroyed post-verification. These promises are worth less than the pixels they’re displayed on. Once data is collected, it exists. It can be hacked. It can be subpoenaed. It can be repurposed. The fine for violations, up to AUD 9.5 million, sounds impressive until you realise that’s pocket change for tech giants making billions annually.

We’re creating a massive honeypot of sensitive information about children and families, and we’re trusting companies with questionable data stewardship records to protect it. What could possibly go wrong?

The Global Domino Delusion

Proponents like US Senator Josh Hawley and author Jonathan Haidt praise Australia’s ban as a “bold precedent” that will trigger global reform. This is wishful thinking bordering on delusion. What Australia has actually created is a case study in how not to regulate technology.

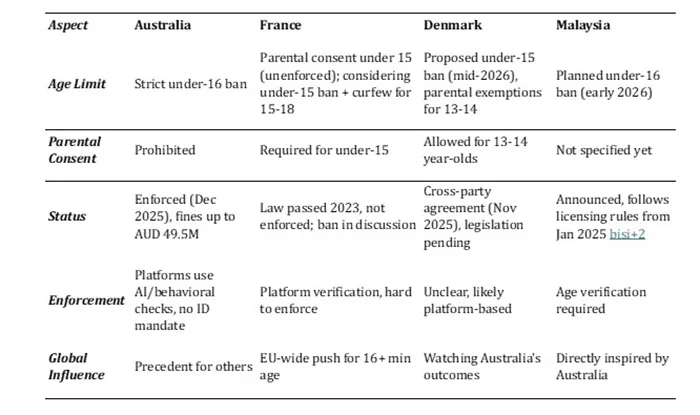

France, Denmark, and Malaysia are watching, but with notable differences. France’s model includes parental consent options. Denmark proposes exemptions for 13-14-year-olds with parental approval. These approaches recognise what Australia refuses to acknowledge: that blanket prohibitions fail to account for individual circumstances and family autonomy.

The comparison table in the document reveals the stark rigidity of Australia’s approach. It’s the only country attempting outright prohibition without parental consent. This isn’t leadership; it’s extremism. Other nations may cherry-pick elements of Australia’s approach while avoiding its most draconian features. (See Table)

The Real Solutions We’re Ignoring

Here’s what actual child protection would look like: holding platforms legally accountable for algorithmic harm, mandating transparent content moderation, requiring platforms to offer chronological feeds instead of engagement-maximising algorithms, funding digital literacy programmes in schools, properly resourcing mental health services for young people, and empowering parents with better tools to guide their children’s online experiences.

Instead, Australia has chosen the path of least intellectual effort: ban it and hope for the best. This is governance by bumper sticker, policy by panic.

Mia Bannister, whose son’s suicide has been invoked repeatedly to justify the ban, called parental enforcement “short-term pain, long-term gain” and urged families to remove devices entirely. But her tragedy, however heart-wrenching, doesn’t justify bad policy. Individual cases, no matter how emotionally compelling, are poor foundations for sweeping legislation affecting millions.

Conclusion: The Tyranny of Good Intentions

Australia’s social media ban is built on good intentions, genuine concerns about child welfare, and understandable frustration with unaccountable tech giants. But good intentions pave a very particular road, and this road leads to a place where governments dictate what information citizens can access based on age, where privacy becomes a quaint relic, and where young people are infantilised rather than educated.

The ban will fail on its own terms, teenagers will circumvent it, platforms will struggle with enforcement, and the mental health crisis will continue because it was never primarily about social media. But it will succeed in normalising digital authoritarianism, expanding surveillance infrastructure, and teaching young Australians that their rights are negotiable commodities.

When this ban inevitably fails, when the promised mental health improvements don’t materialize, when data breaches expose the verification systems, and when teenagers continue to access prohibited platforms through VPNs and workarounds, Australia will face a choice: double down on enforcement, creating an even more invasive surveillance state, or admit that the entire exercise was a costly mistake.

Smart money says they’ll choose the former. After all, once governments acquire new powers, they rarely relinquish them willingly. And that’s the real danger here, not that Australia will fail to protect children from social media, but that it will succeed in building the infrastructure for a far more intrusive state. The platforms may be the proximate target, but the ultimate casualties will be freedom, privacy, and trust.

Australia didn’t need a world-first ban. It needed world-class thinking. Instead, it settled for a world of trouble.

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT, Malabe. The views and opinions expressed in this article are personal.)

Features

Sustaining good governance requires good systems

A prominent feature of the first year of the NPP government is that it has not engaged in the institutional reforms which was expected of it. This observation comes in the context of the extraordinary mandate with which the government was elected and the high expectations that accompanied its rise to power. When in opposition and in its election manifesto, the JVP and NPP took a prominent role in advocating good governance systems for the country. They insisted on constitutional reform that included the abolition of the executive presidency and the concentration of power it epitomises, the strengthening of independent institutions that overlook key state institutions such as the judiciary, public service and police, and the reform or repeal of repressive laws such as the PTA and the Online Safety Act.

The transformation of a political party that averaged between three to five percent of the popular vote into one that currently forms the government with a two thirds majority in parliament is a testament to the faith that the general population placed in the JVP/ NPP combine. This faith was the outcome of more than three decades of disciplined conduct in the aftermath of the bitter experience of the 1988 to 1990 period of JVP insurrection. The manner in which the handful of JVP parliamentarians engaged in debate with well researched critiques of government policy and actions, and their service in times of disaster such as the tsunami of 2004 won them the trust of the people. This faith was bolstered by the Aragalaya movement which galvanized the citizens against the ruling elites of the past.

In this context, the long delay to repeal the Prevention of Terrorism Act which has earned notoriety for its abuse especially against ethnic and religious minorities, has been a disappointment to those who value human rights. So has been the delay in appointing an Auditor General, so important in ensuring accountability for the money expended by the state. The PTA has a long history of being used without restraint against those deemed to be anti-state which, ironically enough, included the JVP in the period 1988 to 1990. The draft Protection of the State from Terrorism Act (PSTA), published in December 2025, is the latest attempt to repeal and replace the PTA. Unfortunately, the PSTA largely replicates the structure, logic and dangers of previous failed counter terrorism bills, including the Counter Terrorism Act of 2018 and the Anti Terrorism Act proposed in 2023.

Misguided Assumption

Despite its stated commitment to rule of law and fundamental rights, the draft PTSA reproduces many of the core defects of the PTA. In a preliminary statement, the Centre for Policy Alternatives has observed among other things that “if there is a Detention Order made against the person, then in combination, the period of remand and detention can extend up to two years. This means that a person can languish in detention for up to two years without being charged with a crime. Such a long period again raises questions of the power of the State to target individuals, exacerbated by Sri Lanka’s history of long periods of remand and detention, which has contributed to abuse and violence.” Human Rights lawyer Ermiza Tegal has warned against the broad definition of terrorism under the proposed law: “The definition empowers state officials to term acts of dissent and civil disobedience as ‘terrorism’ and will lawfully permit disproportionate and excessive responses.” The legitimate and peaceful protests against abuse of power by the authorities cannot be classified as acts of terror.

The willingness to retain such powers reflects the surmise that the government feels that keeping in place the structures that come from the past is to their benefit, as they can utilise those powers in a crisis. Due to the strict discipline that exists within the JVP/NPP at this time there may be an assumption that those the party appoints will not abuse their trust. However, the country’s experience with draconian laws designed for exceptional circumstances demonstrates that they tend to become tools of routine governance. On the plus side, the government has given two months for public comment which will become meaningful if the inputs from civil society actors are taken into consideration.

Worldwide experience has repeatedly demonstrated that integrity at the level of individual leaders, while necessary, is not sufficient to guarantee good governance over time. This is where the absence of institutional reform becomes significant. The aftermath of Cyclone Ditwah in particular has necessitated massive procurements of emergency relief which have to be disbursed at maximum speed. There are also significant amounts of foreign aid flowing into the country to help it deal with the relief and recovery phase. There are protocols in place that need to be followed and monitored so that a fiasco like the disappearance of tsunami aid in 2004 does not recur. To the government’s credit there are no such allegations at the present time. But precautions need to be in place, and those precautions depend less on trust in individuals than on the strength and independence of oversight institutions.

Inappropriate Appointments

It is in this context that the government’s efforts to appoint its own preferred nominees to the Auditor General’s Department has also come as a disappointment to civil society groups. The unsuitability of the latest presidential nominee has given rise to the surmise that this nomination was a time buying exercise to make an acting appointment. For the fourth time, the Constitutional Council refused to accept the president’s nominee. The term of the three independent civil society members of the Constitutional Council ends in January which would give the government the opportunity to appoint three new members of its choice and get its way in the future.

The failure to appoint a permanent Auditor General has created an institutional vacuum at a critical moment. The Auditor General acts as a watchdog, ensuring effective service delivery promoting integrity in public administration and providing an independent review of the performance and accountability. Transparency International has observed “The sequence of events following the retirement of the previous Auditor General points to a broader political inertia and a governance failure. Despite the clear constitutional importance of the role, the appointment process has remained protracted and opaque, raising serious questions about political will and commitment to accountability.”

It would appear that the government leadership takes the position they have been given the mandate to govern the country which requires implementation by those they have confidence in. This may explain their approach to the appointment (or non-appointment) at this time of the Auditor General. Yet this approach carries risks. Institutions are designed to function beyond the lifespan of any one government and to protect the public interest even when those in power are tempted to act otherwise. The challenge and opportunity for the NPP government is to safeguard independent institutions and enact just laws, so that the promise of system change endures beyond personalities and political cycles.

by Jehan Perera

Features

General education reforms: What about language and ethnicity?

A new batch arrived at our Faculty again. Students representing almost all districts of the country remind me once again of the wonderful opportunity we have for promoting social and ethnic cohesion at our universities. Sadly, however, many students do not interact with each other during the first few semesters, not only because they do not speak each other’s language(s), but also because of the fear and distrust that still prevails among communities in our society.

A new batch arrived at our Faculty again. Students representing almost all districts of the country remind me once again of the wonderful opportunity we have for promoting social and ethnic cohesion at our universities. Sadly, however, many students do not interact with each other during the first few semesters, not only because they do not speak each other’s language(s), but also because of the fear and distrust that still prevails among communities in our society.

General education reform presents an opportunity to explore ways to promote social and ethnic cohesion. A school curriculum could foster shared values, empathy, and critical thinking, through social studies and civics education, implement inclusive language policies, and raise critical awareness about our collective histories. Yet, the government’s new policy document, Transforming General Education in Sri Lanka 2025, leaves us little to look forward to in this regard.

The policy document points to several “salient” features within it, including: 1) a school credit system to quantify learning; 2) module-based formative and summative assessments to replace end-of-term tests; 3) skills assessment in Grade 9 consisting of a ‘literacy and numeracy test’ and a ‘career interest test’; 4) a comprehensive GPA-based reporting system spanning the various phases of education; 5) blended learning that combines online with classroom teaching; 6) learning units to guide students to select their preferred career pathways; 7) technology modules; 8) innovation labs; and 9) Early Childhood Education (ECE). Notably, social and ethnic cohesion does not appear in this list. Here, I explore how the proposed curriculum reforms align (or do not align) with the NPP’s pledge to inculcate “[s]afety, mutual understanding, trust and rights of all ethnicities and religious groups” (p.127), in their 2024 Election Manifesto.

Language/ethnicity in the present curriculum

The civil war ended over 15 years ago, but our general education system has done little to bring ethnic communities together. In fact, most students still cannot speak in the “second national language” (SNL) and textbooks continue to reinforce negative stereotyping of ethnic minorities, while leaving out crucial elements of our post-independence history.

Although SNL has been a compulsory subject since the 1990s, the hours dedicated to SNL are few, curricula poorly developed, and trained teachers few (Perera, 2025). Perhaps due to unconscious bias and for ideological reasons, SNL is not valued by parents and school communities more broadly. Most students, who enter our Faculty, only have basic reading/writing skills in SNL, apart from the few Muslim and Tamil students who schooled outside the North and the East; they pick up SNL by virtue of their environment, not the school curriculum.

Regardless of ethnic background, most undergraduates seem to be ignorant about crucial aspects of our country’s history of ethnic conflict. The Grade 11 history textbook, which contains the only chapter on the post-independence period, does not mention the civil war or the events that led up to it. While the textbook valourises ‘Sinhala Only’ as an anti-colonial policy (p.11), the material covering the period thereafter fails to mention the anti-Tamil riots, rise of rebel groups, escalation of civil war, and JVP insurrections. The words “Tamil” and “Muslim” appear most frequently in the chapter, ‘National Renaissance,’ which cursorily mentions “Sinhalese-Muslim riots” vis-à-vis the Temperance Movement (p.57). The disenfranchisement of the Malaiyaha Tamils and their history are completely left out.

Given the horrifying experiences of war and exclusion experienced by many of our peoples since independence, and because most students still learn in mono-ethnic schools having little interaction with the ‘Other’, it is not surprising that our undergraduates find it difficult to mix across language and ethnic communities. This environment also creates fertile ground for polarizing discourses that further divide and segregate students once they enter university.

More of the same?

How does Transforming General Education seek to address these problems? The introduction begins on a positive note: “The proposed reforms will create citizens with a critical consciousness who will respect and appreciate the diversity they see around them, along the lines of ethnicity, religion, gender, disability, and other areas of difference” (p.1). Although National Education Goal no. 8 somewhat problematically aims to “Develop a patriotic Sri Lankan citizen fostering national cohesion, national integrity, and national unity while respecting cultural diversity (p. 2), the curriculum reforms aim to embed values of “equity, inclusivity, and social justice” (p. 9) through education. Such buzzwords appear through the introduction, but are not reflected in the reforms.

Learning SNL is promoted under Language and Literacy (Learning Area no. 1) as “a critical means of reconciliation and co-existence”, but the number of hours assigned to SNL are minimal. For instance, at primary level (Grades 1 to 5), only 0.3 to 1 hour is allocated to SNL per week. Meanwhile, at junior secondary level (Grades 6 to 9), out of 35 credits (30 credits across 15 essential subjects that include SNL, history and civics; 3 credits of further learning modules; and 2 credits of transversal skills modules (p. 13, pp.18-19), SNL receives 1 credit (10 hours) per term. Like other essential subjects, SNL is to be assessed through formative and summative assessments within modules. As details of the Grade 9 skills assessment are not provided in the document, it is unclear whether SNL assessments will be included in the ‘Literacy and numeracy test’. At senior secondary level – phase 1 (Grades 10-11 – O/L equivalent), SNL is listed as an elective.

Refreshingly, the policy document does acknowledge the detrimental effects of funding cuts in the humanities and social sciences, and highlights their importance for creating knowledge that could help to “eradicate socioeconomic divisions and inequalities” (p.5-6). It goes on to point to the salience of the Humanities and Social Sciences Education under Learning Area no. 6 (p.12):

“Humanities and Social Sciences education is vital for students to develop as well as critique various forms of identities so that they have an awareness of their role in their immediate communities and nation. Such awareness will allow them to contribute towards the strengthening of democracy and intercommunal dialogue, which is necessary for peace and reconciliation. Furthermore, a strong grounding in the Humanities and Social Sciences will lead to equity and social justice concerning caste, disability, gender, and other features of social stratification.”

Sadly, the seemingly progressive philosophy guiding has not moulded the new curriculum. Subjects that could potentially address social/ethnic cohesion, such as environmental studies, history and civics, are not listed as learning areas at the primary level. History is allocated 20 hours (2 credits) across four years at junior secondary level (Grades 6 to 9), while only 10 hours (1 credit) are allocated to civics. Meanwhile, at the O/L, students will learn 5 compulsory subjects (Mother Tongue, English, Mathematics, Science, and Religion and Value Education), and 2 electives—SNL, history and civics are bunched together with the likes of entrepreneurship here. Unlike the compulsory subjects, which are allocated 140 hours (14 credits or 70 hours each) across two years, those who opt for history or civics as electives would only have 20 hours (2 credits) of learning in each. A further 14 credits per term are for further learning modules, which will allow students to explore their interests before committing to a A/L stream or career path.

With the distribution of credits across a large number of subjects, and the few credits available for SNL, history and civics, social/ethnic cohesion will likely remain on the back burner. It appears to be neglected at primary level, is dealt sparingly at junior secondary level, and relegated to electives in senior years. This means that students will be able to progress through their entire school years, like we did, with very basic competencies in SNL and little understanding of history.

Going forward

Whether the students who experience this curriculum will be able to “resist and respond to hegemonic, divisive forces that pose a threat to social harmony and multicultural coexistence” (p.9) as anticipated in the policy, is questionable. Education policymakers and others must call for more attention to social and ethnic cohesion in the curriculum. However, changes to the curriculum would only be meaningful if accompanied by constitutional reform, abolition of policies, such as the Prevention of Terrorism Act (and its proxies), and other political changes.

For now, our school system remains divided by ethnicity and religion. Research from conflict-ridden societies suggests that lack of intercultural exposure in mono-ethnic schools leads to ignorance, prejudice, and polarized positions on politics and national identity. While such problems must be addressed in broader education reform efforts that also safeguard minority identities, the new curriculum revision presents an opportune moment to move this agenda forward.

(Ramya Kumar is attached to the Department of Community and Family Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Jaffna).

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.

by Ramya Kumar

-

News1 day ago

News1 day agoMembers of Lankan Community in Washington D.C. donates to ‘Rebuilding Sri Lanka’ Flood Relief Fund

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoPope fires broadside: ‘The Holy See won’t be a silent bystander to the grave disparities, injustices, and fundamental human rights violations’

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoPakistan hands over 200 tonnes of humanitarian aid to Lanka

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoUnlocking Sri Lanka’s hidden wealth: A $2 billion mineral opportunity awaits

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoArmy engineers set up new Nayaru emergency bridge

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoOfficials of NMRA, SPC, and Health Minister under pressure to resign as drug safety concerns mount

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoExpert: Lanka destroying its own food security by depending on imported seeds, chemical-intensive agriculture

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoFlawed drug regulation endangers lives