Midweek Review

Brecht’s Chalk Circle Again and Again

Azdak’s Judgments:

by Laleen Jayamanne

Soldier: Your Honour, we meant no harm. Your Honour, what do you wish?

Azdak: Nothing, fellow dogs. Or just an occasional boot to lick!

[…]

Fetch me wine, red wine, sweet red wine.

‘In a faraway and long-ago, dark and bloody epoch, in a sunburnt and cursed city, there lived a Duke…’ sang the storyteller. In the mid-’60s when Brecht’s Caucasian Chalk Circle was first performed there, Colombo had ceased being dark and bloody. April ‘71 was yet a few years away. But the effects of the Sinhala Only Act of ‘56 were taking root in educational institutions, like the National School of Art and Crafts, creating a myopic, monolingual culture. In this context, Henry Jayasena and others in the Sinhala theatre who were interested in developing contemporary drama, began to translate modern European plays, originally written in German, Russian and Italian. Crucially, these Sinhala versions were drawn from English translations of the original languages of the plays. So English worked as the essential ‘link’ language without which we would not have had any access to world theatre and much else. Henry had a good command of English, learnt in high school and at Teachers’ College. Like his similarly brilliant contemporary Sugathapala de Silva, he was not a University educated artist. But Jayasena’s superb theatrical imagination allowed him to translate from English the Chalk Circle into a most wonderful colloquial poetic Sinhala idiom. So much so that it feels like the play was written originally in Sinhala! Reading the Sinhala script was a pleasure in itself and sections have remained in my old brain, as good poetry does. The epic techniques of supple shifts from the songs of the narrator, to the every-day racy, bawdy dialogue of the soldiers, to the lyrical love passages between Grusha and Simon Shashava, to the absurdist folk utterances of Azdak, are all memorably crafted and differentiated.

Bertolt Brecht’s Epic play written in 1944 while he was in exile in the US, fleeing Hitler’s fascist Germany, continues to be a vibrant part of Lanka’s living ‘theatrical epic-memory’. Also, as a text for the O’Level, a large number of Lankans must have become familiar with it. The play has a ‘play-within-a-play’ double structure but in scene 4, Azdak’s story, there is a further third level. That is, a ‘play-within-a play-within-a play’. The first play is set in the present postwar Soviet Republic of Georgia in 1945, where workers of two Collective Farms meet with a State official to decide, through discussion, as to who should have the stewardship of a particular valley. The Farmers who have been in the valley since birth claim it as their own for their goats to graze in, while the other group say that through irrigation they can make the valley more productive of fruit and wine. Its key question is, ‘who is good for the land?’

The play-within the play, set in the Imperial past of a fictional Georgia or Grusinia, at war with Persia. The folk parable of the Chalk Circle is performed as entertainment after the debate about the valley has been reasonably decided. The key question there becomes, ‘who is the good mother for the child?’ – (hadu mavada, vadu mavada? The third level of a play-within a play-within a play is a mock trial between a prince who wants to be the Judge and Azdak pretending to be the deposed Grand Duke, as the defendant. In all there are six or seven judgments that involve Azdak in one way or another. The intricacies of each of these legal cases and their differences from each other, make scene 4 a most fascinating aspect of the episodic structure of the play itself. In contrast, scenes 1-3 involving Grusha the kitchen-hand and her dilemma are expressed memorably and clearly by the narrator: “Terrible is the temptation to be good.” This is Grusha’s decision to save and nurture the Governor’s abandoned infant, without counting the terrible cost to herself. Her scenes, engaging as they are, do not have the kind of intricacy and complexity of the six or so episodes where Azdak plays with several ideas of Law and of Justice.

Animals’ Rights and the Folk Imagination

An Epic Contest is staged in the play, between the idea of The Law as a written code by absolutist rulers, and ideas of Social Justice, which include a sense of fairness towards the poor and powerless. This ample human feeling of fairness is encoded in folk tales of peoples across Eurasia where animals also have a claim on Justice from humans. For example, the Mahavamsa tells us of the remarkable sense of justice embodied by the Tamil King Elara when he ruled Anuradhapura. He had a bell hung at his palace gate, which anyone could ring to make a claim when an injustice had been committed. So, when a cow complained to Elara that his son in his chariot had run over and killed her calf, he did not hesitate to put his son to death. We are told that taking pity on them, both lives were restored by a god. According to my friend Amrit MacIntyre who is a lawyer and legal scholar that story is found in various forms in the Middle East to Europe. Each version of the story is about a king from the distant past who is known for his justice. Critically, in each version the person seeking justice was an animal, a serpent in Italy seeking justice from Charlemagne, and an ass in the Middle East seeking justice from an Iranian Emperor (Khusro I). What is intriguing in all of this is a common conception of justice equally applying to all, including animals, that forms part of the mental landscape across Eurasia from very early on. Interestingly, a 2017 decision of the Supreme Court of India referred to the story of Elara as part of its reasoning! The folk tale of the Chalk Circle is found in an ancient Chinese play, as well as in the Judgment of Solomon in the Old Testament, and both were points of reference for Brecht in radically rewriting the tale as a modern epic parable influenced by Marxist ideas.

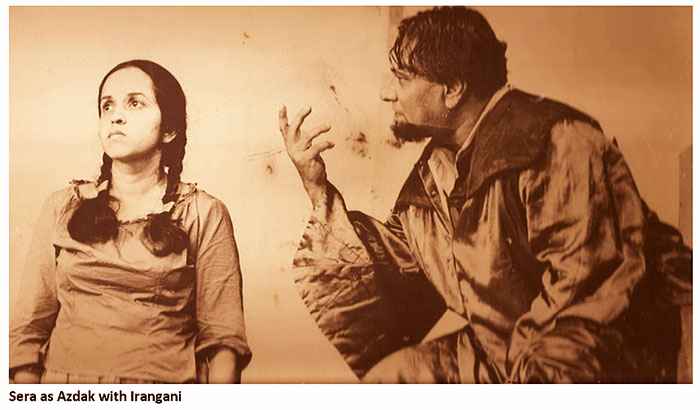

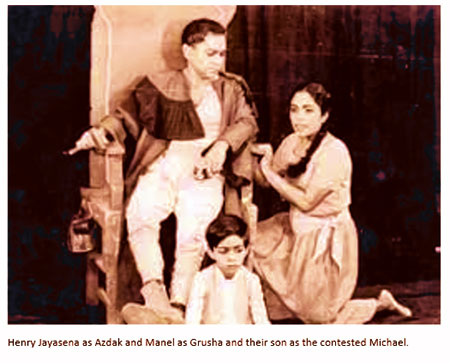

Azdak, the town scribe and rogue judge, was played memorably by Winston Serasinghe in Ernest MacIntyre’s English production. Henry Jayasena played the same in his own production, also in the mid-60s. And MacIntyre also acted as the priest in Henry’s production – one of the earliest exchanges between English and Sinhala Theatre in the ‘60s. That is to say, between the Lionel Wendt and Lumbini theatres, respectively. Azdak was the village scribe who, when the State collapsed and the official judge hanged by the rebellious carpet weavers, was forcibly roped in to act as a judge by the illiterate soldiers. But it turned out that he had his own eccentric ideas of Justice and fair play and was a bit drunk, sexist and openly took money from plaintiffs. Though Azdak appears only in the last 2 scenes, he leaves a powerful impression in one’s memory as a character like Shakespeare’s Falstaff. But he is unlike Falstaff whose fall from grace, after rejection by his former buddy Prince Hal, is full of tragic pathos. Azdak is a creature of the folk imagination.

Epic-Character Azdak

Sumathy Sivamohan concludes her recent article on the links between the two Republican Constitutions of Sri Lanka (‘72 & ‘78), by invoking Azdak as a figure relevant to this moment of the People’s Aragalaya, (The Island 8/8). Azdak is a Brechtian Epic-Character through whom the very ideas of Law and Justice are examined, played with, debated and put into crisis, theatrically. He is also a great comic figure introducing laughter into the court where it is thought to be unseemly. In this way Brecht’s Epic Theatrical practice offers us several unusual angles on the process of making Judgements, the reasoning behind them. Through these scenes, the idea of Justice appears paradoxical, not altogether just in one case, but also both reasonable and yet ‘unlawful’, if judged according to the letter of the Law, in another. And some downright absurd. This complexity, of plot lines and intricacy of comic procedural ‘legal’ detail, is significant in demonstrating the class basis of judgements and how they are reached. The hilarious comic absurdity of some of Azdak’s arguments and rulings parody seemingly rational, legalistic linguistic power-play in regular courts. ‘Demonstrability’ is a strong concept in Brechtian theatrical theory and is linked to the idea of the pedagogical function of Epic Theatre.

A Brechtian Parable for the Aragalaya?

The comedic demonstration of the interplay between the Law and Justice, appears to be relevant to Lankans now, poised in their struggle to make politicians accountable for their actions which have plunged the country into economic, political and existential chaos. Azdak is an epic construct and as such we don’t quite empathise with him or like or dislike him. Rather, we observe this comic figure with enjoyment, as he plays with a variety of judgments, with no rule book as guide. He excites our curiosity about the mechanics of the Law, its different avatars, (Totalitarian Law, People’s Law, a judgment without a precedent), which, in an Imperial regime, as in the world of the play within the play, seems invincible and arbitrary. The two lawyers of the Governor’s wife Natella Abashvili are, however, immediately recognisable social types aligned with social power, contrasting with Azdak’s Epic singularity. They argue for the right of the blood-line to obtain the child from Grusha, to return to his biological but callous and predatory mother, only so that she can claim the property bequeathed to the child.

A Palace Revolution

The Chalk Circle opens on a seemingly normal Easter Sunday, with the wealthy Governor and family attending church to great fanfare that soon turns violent – palace revolution creates chaos and soldiers go to war against distant Persia. The Governor is beheaded, his head impaled on a lance and displayed, nailed to a wall, while his wife flees forgetting to take their baby. The Grand Duke has also gone into hiding. The Carpet Weavers, taking advantage of the revolt, hang the Judge. So it comes to pass that the village scribe Azdak becomes the accidental Judge, under a state of emergency. Not knowing the Law is no impediment to Azdak. Some of these events and scenes of the play have an uncanny resemblance to the farcical misrule seen in the Lankan Parliament not too long ago. Before we look at Azdak’s celebrated Judgments it’s worth looking at Brecht’s original theatrical structure, which is Epic rather than Dramatic.

Epic Theatre vs Tragic Drama

Brecht’s play is not a tragedy, a genre he rejected as an Aristotelian Greek notion driven by an idea of Destiny and causality and heroic action. The presence of a singer-narrator who introduces us to the play is an epic device in that, as the story-teller, he conducts the action. He stops characters in their tracks and sings of what they feel, but cannot say. He explains the action when necessary and advances the story. The famous singer who knows twenty-one thousand lines of verse becomes the story-teller. He announces that the play consists of ‘two stories and will take two hours to perform’. The Soviet expert from the city is impatient and asks him, (after the disagreement between the two collective farmers is resolved), “can’t you make it shorter?” The singer responds with a firm ‘No’. Brecht offers a play, which is profoundly episodic in its construction. Each episode is autonomous, has a relative freedom from a tight causally driven dramatic structure. What Brecht wanted was a theatrical structure which didn’t have any inevitable causal links propelling events as in the case of, say, Oedipus Rex. In this way he demonstrates how History and its presentation in the Epic, hold alternative possibilities. The Epic form can reveal in its episodic structure ‘the many roads not taken’. Some academics in the Aragalaya have begun to examine Lanka’s post independent history and the many roads not taken in structuring the economy, in race relations and education and development policy, for instance.

Brecht’s play is not a tragedy, a genre he rejected as an Aristotelian Greek notion driven by an idea of Destiny and causality and heroic action. The presence of a singer-narrator who introduces us to the play is an epic device in that, as the story-teller, he conducts the action. He stops characters in their tracks and sings of what they feel, but cannot say. He explains the action when necessary and advances the story. The famous singer who knows twenty-one thousand lines of verse becomes the story-teller. He announces that the play consists of ‘two stories and will take two hours to perform’. The Soviet expert from the city is impatient and asks him, (after the disagreement between the two collective farmers is resolved), “can’t you make it shorter?” The singer responds with a firm ‘No’. Brecht offers a play, which is profoundly episodic in its construction. Each episode is autonomous, has a relative freedom from a tight causally driven dramatic structure. What Brecht wanted was a theatrical structure which didn’t have any inevitable causal links propelling events as in the case of, say, Oedipus Rex. In this way he demonstrates how History and its presentation in the Epic, hold alternative possibilities. The Epic form can reveal in its episodic structure ‘the many roads not taken’. Some academics in the Aragalaya have begun to examine Lanka’s post independent history and the many roads not taken in structuring the economy, in race relations and education and development policy, for instance.

Azdak’s Judgements

Why do I think that a ‘close reading’ of Azdak’s judgements matter, especially now? Because he has a window of opportunity during a palace revolution, to play with and interrogate ideas of Law and Justice. It is quite by chance that he is made a judge because the official judge has been hanged, the Governor executed and the Duke has fled during the civil war. Now is a time when a large number of people in Lanka are feeling that the Laws that govern them and their sense of Justice are at variance. And Azdak’s idiosyncratic process of judging and his rulings offer several unusual angles on both. He is unprincipled and we can’t tell which way his Judgment will fall, regardless of his own precedent. He is inconsistent but not amoral, he shows feelings on the bench, he is not ‘Blind Justice’. He has a strong conscience. Guilt-ridden, he has himself arrested and shackled by Sauwa the cop, for having unwittingly given the fugitive Grand Duke refuge in his hut and helped him escape, during the palace revolution.

In the mock trial Azdak impersonates the Grand Duke. The soldiers who call the shots say they want to test if the Nephew is fit and proper to be a judge as recommended by his uncle Prince Kazbeki. So they create a legal play within the play by making Azdak play the role of the Grand Duke as the defendant and the Nephew the acting judge. Azdak as the Grand Duke is accused of losing the war and in his comic defense he demonstrates how the Princes actually won by war-profiteering and enabling the Persians victory. All this is done in a brilliant quick-witted, punchy question and answer session where Azdak twists words and wins the argument with relish. Proven guilty of embezzlement, the soldiers arrest the acting judge and Prince Kazbeki and plonk Azdak on the throne, unceremoniously throwing the cloak of the dead judge across his shoulders. It’s high farce with linguistic fireworks in court.

A judgement Azdak makes from the bench deals with a farmer’s complaint against his farmhand who is accused of raping his daughter-in-law, Ludovica. By contemporary feminist standards Azdak’s judgment that Ludovica by virtue of her seductive walk, seduced and thereby ‘raped’ the man, is idiotic and sexist. But the scene is more ambiguous. It might be the case that what was called rape by the father-in-law may have been consensual sex, which he happened to stumble in on. We are told by the narrator that the Ludovica’s speech was well rehearsed. The scene remains ambiguous, open to several readings especially because Azdak orders Ludovica to accompany him to examine the scene of the crime after the verdict has found her guilty! The narrator has called him, ‘Good judge, bad judge, Azdak.’

Another judgment shows that Azdak is indeed a ‘people’s judge,’ ruling in favour of a grandmotherly old woman, against the three farmers who accuse her of theft. The old woman wins the case by virtue of being poor, despite the fact that the items were stolen on her behalf by a relative who is a Bandit. The plea she offers in her defense is her belief in miracles. So, taking up her cue Azdak reprimands the Farmers for not believing in miracles! To save time, Azdak decides to hear two similar cases of professional negligence and blackmail, together!

The judgment of the Chalk Circle is what Azdak is most famous for. But the previous ones, with their pileup of parodic absurdity, are crucial for Brecht’s politics in Demonstrating how social class, wealth and power determine legal ritual. Once the normality of the Grand Duke’s authoritarian rule is restored, Prince Kazbeki is beheaded as a traitor. The chaos of the revolutionary moment (‘a Golden age’?) that saw Azdak become a judge, with his own unique sense of justice, is reversed with the return of the Grand Duke. He is now attacked by the illiterate soldiers, bloodied and humiliated, soon to be hanged. But at the last moment a messenger from the Grand Duke arrives with a document ordering Azdak to be exonerated and made judge for having saved the Duke’s life. It is jarring to register that the Grand Duke does have a sense of aristocratic honour (unlike Lanka’s rulers) despite his reputation as a swindler and butcher.

Azdak wipes the blood from his eyes as he finds himself plonked on the judges’ chair yet again, and makes the celebrated progressive modern judgment of the Chalk Circle. It is reached through an ingenious process based on an ancient wordless contest. Grusha repeatedly refuses to pull the child out of the circle lest he be injured and so she is deemed the ‘true’ mother and given custody of the child, against the predatory biological mother who pulls him out. The singer then concludes the epic parable with a poetic summary of how Azdak aligned a feeling of Justice with eminently reasonable new rules. In that legal thinking, human emotion becomes the sister of rational thought.

Singer:

“The people of Georgia

Remembered him, and remembered

For a long time,

The times when he was judge

As a short, golden age

When there was justice – nearly.

Take to heart,

All you who’ve heard

The Tale of the Chalk Circle

And what that ancient song means.

What there is should belong

To those who are good at it.

Children to true mothers,

That they may thrive.

Carts to the good drivers,

That they may be driven well,

And the valley to the waterers,

So that it bears fruit.”

Sri Lanka is a country in which Chalk Circle has been seen and enjoyed for generations. Doing a close reading of the play, while following the non-violent political uprising and struggle of the people from afar, gives one hope that changes good for Lanka are imaginable so that the land may bear fruit.

Midweek Review

A question of national pride

President Anura Kumara Dissanayake, who also holds the Finance and Defence portfolios, caused controversy last year when the Defence Ministry announced that he wouldn’t attend the National Victory Day event. Angry public reactions over social media compelled the President to change his decision. He attended the event. Whatever his past and for what he stood for as the President and the Commander-in-Chief of our armed forces, Dissanayake cannot, under any circumstances, shirk his responsibilities. The next National Victory Day event is scheduled in mid-May. The event coincides with the day, May 18, when the entire country was brought back under government control and the Army put a bullet through Prabhakaran’s head as he hid in the banks of the Nanthikadal lagoon, on the following day. The government also forgot the massive de-mining operations undertaken by the military to pave the way for the resettlement of people, rehabilitation of nearly 12,000 terrorists, and maintaining UN troop commitments, even during the war.

By Shamindra Ferdinando

The majestic presence of Field Marshal Sarath Fonseka, Admiral of the Fleet Wasantha Karannagoda and Marshal of the Air Force Roshan Goonetileke, though now more than 16 years after that historic victory, represented the war-winning armed forces at the 78 Independence Day celebrations. Their attendance reminded the country of Sri Lanka’s greatest post-independence accomplishment, the annihilation of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in May 2009.

Among the other veterans at the Independence Square event was General Shavendra Silva, the wartime General Officer Commanding (GOC) of the celebrated 58 Division. The 58 Division played a crucial role in the overall Vanni campaign that brought the LTTE down to its knees.

The 55 (GOC Maj. Gen. Kamal Gunaratne) and 53 Divisions (GOC Brig. Prasanna Silva) that had been deployed in the Jaffna peninsula, as well as newly raised formations 57 Division (GOC Maj. Gen. Jagath Dias), 58 Division and 59 Division (Brig. Nandana Udawatta), obliterated the LTTE.

Chagie Gallage, Fonseka’s first choice to command the 58 Division (former Task Force 1) following his exploits in the East, but had to leave the battlefield due to health issues then, rejoined the Vanni campaign at a decisive stage. Please forgive the writer for his inability to mention all those who gave resolute leadership on the ground due to limitations of space. The LTTE that genuinely believed in its battlefield invincibility was crushed within two years and 10 months. Of the famed ex-military leadership, Fonseka was the only one with no shame to publicly declare support for ‘Aragalaya,’ forgetting key personalities in the Rajapaksa government who helped him along the way to crush the Tigers, especially after the attempt on his life by a female LTTE suicide bomber, inside the Army Headquarters, when he had to direct all military operations from Colombo. And he went to the extent of addressing US- and India-backed protesters before they stormed President’s House on the afternoon of July 9, 2022. President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, wartime Defence Secretary, whose contribution can never be compared with any other, had to flee Janadhipathi Mandiyara and take refuge aboard SLNS Gajabahu, formerly of the US Coast Guard. The same sinister mob earlier ousted him from his private residence, at Mirihana, that he occupied previously without being a burden to the state. It was only after the attack on his private residence on March 31, 2022, that he came to reside in the official residence, the President’s House.

The presence of Fonseka, Karannagoda and Goonetileke at the Independence Day commemoration somewhat compensated for the pathetic failure on the part of the government to declare, during the parade, even by way of a few words, the armed forces historic triumph over the LTTE against predictions by many a self- proclaimed expert to the contrary. That treacherous and disgraceful decision brought shame on the government. Social media relentlessly attacked the government. To make matters worse, the elite Commandos and Special Forces were praised for their role in the post-Cyclone Ditwah situation. The Special Boat Squadron (SBS) and Rapid Action Boat Squadron (RABS), too, were appreciated for their interventions during the post-cyclone period.

The shocking deliberate omission underscored the pathetic nature of the powers that be at a time the country is in a flux. If Cyclone Ditwah hadn’t devastated Sri Lanka, the government probably may not have anything else to say about the elite fighting formations.

The government also left out the main battle tanks, armoured fighting vehicles, tank recovery vehicles and various types of artillery, as well as the multi barrel rocket launchers (MBRLs). The absence of Sri Lanka’s precious firepower on Independence Day shocked the country. The government owes an explanation. Lt. Gen. Lasantha Rodrigo of the Artillery is the 25th Commander of the Army. How did the Commander of the Army feel about the decision to leave the armour and artillery out of the parade?

The combined firepower of armour and artillery caused havoc on the enemy, thanks to deep penetration units that infiltrated behind enemy lines giving precise intelligence on where and what to hit.

The LTTE suffered devastating losses in coordinated attacks mounted during both offensive and defensive action, both in the northern and eastern theatres. The current dispensation would never be able to comprehend the gradual enhancement of armour and artillery firepower over the years to meet the growing LTTE threat. The MBRLs were a game changer. President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga’s government introduced the MBRLs in 2000 in the aftermath of devastating battlefield debacles in the northern theatre. (If all our MBRLs had been discarded after the successful conclusion of the war in May 2009, there is no point in blaming this government for non-display of the monster MBRLs. But, there cannot be any excuse for the government decision not to display the artillery.

Even during the three decades long war and some of the fiercest fighting in the North and East, the armour and artillery were always on display. It would be pertinent to mention the acquisition of Chinese light tanks in 1991, about a year after the outbreak of Eelam War II, and T 55 Main Battle Tanks (MBTs) from the Czech Republic, also during the early ’90s, marked the transformation of the regiment. Let me remind our readers that both Armour and Artillery were deployed on infantry role due to dearth of troops in the northern and eastern theatres.

No kudos for infantry

The Armour and Artillery were followed by the five infantry formations, Sri Lanka Light Infantry (SLLI), Sinha Regiment (SR), Gemunu Watch (GW), Gajaba Regiment (GR) and Vijayabahu Infantry Regiment (VIR). They bore the brunt of the fighting. They spearheaded offensives, sometimes in extremely unfavourable battlefield situations. The team handling the live media coverage conveniently failed to mention their battlefield sacrifices or accomplishments. It was nothing but a treacherous act perpetrated by a government not sensitive at all to the feelings of the vast majority of people.

The infantry was followed by the Mechanized Infantry Regiment (MIR). Raised in February 2007 as the armed forces were engaged in large scale operations in the eastern theatre, and the Vanni campaign was about to be launched, at the formation of the Regiment, it consisted of the third battalion of the SLLI, 10th battalion of SR and 4th battalion of GR. The 5th and 6th Armoured Corps were also added to the MIR. The 4th MIR was established also in February 2008 and after the end of war 21 battalion of the Sri Lanka National Guard was converted to 5 (Volunteer) MIR.

The contingent of MIR troops joined the Independence Day parade, without their armoured vehicles. Perhaps the political leadership seems to be blind to the importance of maintaining military traditions. Field Marshal Fonseka, who ordered the establishment of MIR must have felt really bad at the way the government took the shine off the military parade. What did the government expect to achieve by scaling down the military parade? Obviously, the government appears to be confident that the northern and eastern electorates would respond favourably to such gestures. Whatever the politics in the former war zones, the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP)-led Jathika Jana Balawegaya (JJB) must realise that it cannot, under any circumstances, continue to hurt the feelings of the majority community.

The description of Commandos and Special Forces was restricted to their post-Ditwah rehabilitation role. The snipers were not included in the parade. Motorcycle riding Special Forces, too, were absent. The way the Armour, Artillery, Infantry, as well Commandos and Special Forces were treated, we couldn’t have expected justice to other regiments and corps. In fact, the government didn’t differentiate fighting formations from the National Guard.

The National Guard was raised in Nov. 1989 in the wake of the quelling of the second JVP-led terrorist campaign. Mrs. Sirimavo Bandaranaike’s government swiftly crushed the first JVP bid to seize power in April 1971. The second bid was far worse and for three years the JVP waged a murderous campaign but finally the armed forces and police overwhelmed them. On Nov. 1, 1989, prominent battalions that had been deployed for the protection of politicians were amalgamated to establish the first National Guard battalion and upgraded as a new battalion of the Volunteer Force.

The Navy and Air Force, too, didn’t receive the recognition they deserved. Just a passing reference was made about the Fourth Attack Flotilla, the Navy’s premier offensive arm. The government also forgot the turning point of the war against the LTTE when Karannagoda’s Navy, with US intelligence backing, hunted down Velupillai Prabhakaran’s floating arsenals, on the high seas.

Karannagoda, the writer is certain, must have felt disappointed and angry over the disgraceful handling of the parade. The war-winning armed forces deserved the rightful place at the Independence Day parade.

The government did away with the fly past. Perhaps, the Air Force no longer had the capacity to fly MiG 27s, Kfirs, F 7s and Mi 24s. During the war and after Katunayake-based jet squadrons thundered over the Independence Day parade while the Air Force contingent was saluting the President. Jet squadrons and MI 24s (Current Defence Secretary Air Vice Marshal (retd) Sampath Thuyakontha commanded the No 09 Mi 24 squadron during the war (https://island.lk/govt-responds-in-kind-to-thuyaconthas-salvo/). Goonetileke’s Air Force conducted an unprecedented campaign to inflict strategic blows to the enemy fighting capacity. That was in addition to the SLAF taking out aerial targets and providing close-air-support to ground forces, while also doing a great job in helicopters whisking away troop casualties for prompt medical attention.

Chagie’s salvo

Maj. Gen Chagie Gallage

The armed forces paid a very heavy price to bring the war to a successful conclusion. During the 1981 to 2009 period, the Army lost nearly 24,000 officers and men. Of them, approximately 2,400 died during January-May 2009 when the Vanni formations surrounded and decimated the enemy. (Army, Navy and Air Force as well as police suffered loss of lives during the campaigns against the JVP in 1971 and during the 1987-1989 period) At the crucial final days of the offensive, ground forces were deprived of aerial support in a bid to minimise civilian losses as fleeing Tigers used Tamil civilians they had corralled as a human shield. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) as revealed by Wikileaks acknowledged the armed forces gesture but no government sought to exploit such unintentional support for Sri Lanka’s advantage. That wasn’t an isolated lapse.

In the run-up to the now much discussed 78 Independence Day parade, Gallage caused unprecedented controversy when he warned of possible attempts to shift the Security Forces Headquarters, in Jaffna, to the Vanni mainland. The GR veteran’s social media post sent shockwaves through the country. Gallage, known for his outspoken statements/positions and one of the victims of global sanctions imposed on military leaders, questioned the rationale in vacating the Jaffna Headquarters, central to the overall combined armed forces deployment in the Jaffna peninsula and the islands.

Regarding Gallage’s explosive claim, the writer sought clarification from the government but in vain. About a year after the end of the war, the then government began releasing land held by the armed forces. In line with the post-war reconciliation initiatives, the war-winning Mahinda Rajapaksa government released both government and public property, not only in the Jaffna peninsula, but in all other northern and eastern administrative districts, as well. Since 2010, successive governments have released just over 90 percent of land, once held by the armed forces. Unfortunately, political parties and various local and international organisations, with vested interests, continue to politicise the issues at hand. None of them at least bothered to issue a simple press release demanding that the LTTE halted the forcible recruitment of children, use of women/girls in suicide missions and end reprehensible use of civilian human shields.

The current dispensation has gratefully accepted President Ranil Wickremesinghe’s proposal to reduce the Army strength to 100,000 by 2030. Wickremesinghe took that controversial but calculated decision in line with his overall response to post-Aragalaya developments. The Island learns that the President’s original intention was to downsize the Army to 75,000 but he settled for 100,000.

Whatever those who still cannot stomach the armed forces’ triumph over the LTTE and JVP had to say, the armed forces, without any doubt, are the most respected institution in the country.

Maithripala Sirisena and Ranil Wickremesinghe can never absolve themselves of the responsibility for betraying the armed forces at the Geneva-based United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) in Oct. 2015. The treacherous JVP-backed the Yahapalana government to co-sponsor a US-led accountability resolution. That massive act of unprecedented betrayal should be examined taking into consideration primarily two issues – (1) the Tamil electorate throwing its weight behind Sirisena at the 2015 presidential election at the behest of now defunct Tamil National Alliance [TNA] (2) a tripartite agreement on the setting up of hybrid war crimes court. That agreement involved the US, Sri Lanka and TNA. Let me stress that at the 2010 presidential election, the TNA joined the UNP and the JVP in supporting war-winning Army Commander Fonseka’s candidature at the first-post war national election. Thanks to WikiLeaks, the world knows how the US manipulated the TNA to back Fonseka, the man who spearheaded a ruthless campaign that decimated the LTTE. Fonseka’s Army beat the LTTE, at its own game. Then, the Tamil electorate voted for Fonseka, who won all predominately Tamil speaking electoral districts but suffered a humiliating defeat in the rest of the country.

Let us not forget ex-LTTE cadres as well as members of other Tamil groups who backed successive governments. Tamil men contributed even to clandestine operations behind enemy lines. Unfortunately, successive governments had been pathetic in their approach to counter pro-Eelam propaganda. Sri Lanka never had a tangible action plan to counter those propagating lies. Instead, they turned a blind eye to anti-Sri Lanka campaigns. Dimwitted politicians just played pandu with the issues at hand. The Canadian declaration that Sri Lanka perpetrated genocide in May 2022 humiliated the country. Our useless Parliament didn’t take up that issue while three years later the Labour Party-run UK sanctioned four persons, including Karannagoda and Shavendra Silva, in return for Tamil support at the parliamentary elections there.

Victory parade fiasco

In 2016, the Yahapalana fools cancelled the Victory Day parade, held uninterrupted since 2009 to celebrate the country’s greatest post-independence achievement. By then, the Yahapalana administration had betrayed the armed forces at the UNHRC. The UNP-SLFP combine operated as if the armed forces didn’t exist. Sirisena had no option but to give in to Wickremesinghe’s despicable strategy meant to appease Eelamists whose support he desired, even at the expense of the overall national interest.

The Victory Day parade was meant to mark Sri Lanka’s triumph over separatist Tamil terrorism. It was never intended to humiliate the Tamil community, though the LTTE consisted of Tamil-speaking people. Those who complained bitterly about the May Victory Day celebration never wanted to publicly acknowledge that the eradication of the LTTE saved them from being terrorised any further. All concerned should accept that as long as the LTTE had the wherewithal to wage terror attacks, peace couldn’t have been restored. As Attorney-at-Law Ajaaz Mohamed repeatedly stressed to the writer the importance of UNP leader Wickremesinghe’s genuine efforts to address the national issue, he could have succeeded if the LTTE acted responsibly. The writer is also of the view that Wickremesinghe even risking his political future bent backwards to reach consensus at the negotiating table but the LTTE exploited the 2002 Ceasefire Agreement (CFA) arranged by Norway, to bring down Wickremesinghe’s government.

Wickremesinghe earned the wrath of the Sinhalese for giving into LTTE demands but he struggled to keep the talks on track. Then, the LTTE delivered a knockout blow to his government by withdrawing from the negotiating table, in late April 2003, thereby paving the way for President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga to take over key ministries, including Defence, and set the stage for parliamentary polls in April 2004. The LTTE’s actions made Eelam War IV inevitable.

The armed forces hadn’t conducted a major offensive since 2001 following the disastrous Agnikheela offensive in the Jaffna peninsula. Wickremesinghe went out of his way to sustain peace but the LTTE facilitated Mahinda Rajapaksa’s victory, at the presidential election, to create an environment which it believed conducive for the final war. Having killed the much-respected Foreign Minister Lakshman Kadirgamar, in August 2005, and made suicide attempts on the lives of Sarath Fonseka and Gotabaya Rajapaksa in April and Oct 2006, the LTTE fought well and hard but was ultimately overwhelmed, first in the East and then in North/Vanni in a series of battles that decimated its once powerful conventional fighting capacity. The writer was lucky to visit Puthumathalan waters in late April 2009 as the fighting raged on the ground and the Navy was imposing unprecedented blockade on the Mullaitivu coast.

The LTTE proved its capabilities against the Indian Army, too. The monument at Battaramulla where Indians leaders and other dignitaries, both military and civilian, pay homage, is a reminder of the LTTE fighting prowess. India lost nearly 1,500 officers and men here (1987 to 1990) and then lost one-time Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi in a suicide attack in Tamil Nadu just over a year after New Delhi terminated its military mission here. The rest is history.

Midweek Review

Theatre and Anthropocentrism in the age of Climate Emergency

A few days ago, I was in a remote region of Sri Lanka, Hambantota, a dry zone area, where people mainly live on farming. The farming methods are still very primitive. I was engaged in a television series, titled Beddegama, directed by Priyantha Kolambage. The character I play is ‘Silindu’, a hunter. Silindu is a character created by Leonard Woolf, a colonial administrator, who lived in Sri Lanka in the early 20th century. In his widely read book, Village in the Jungle, Silindu, the hunter lives with his two daughters and his sister in a mud hut in the forest. They are one of the few families in this village struggling to survive amidst drought, famine and overbearing government authority.

Phenomenologically speaking, Silindu is an environmental philosopher. He believes that the jungle is a powerful phenomenon, a living entity. He thinks that the animals who live in the jungle are also human-like beings. He talks to trees and hunts animals only to dull the pangs of hunger. He is an ethical man. He believes that the jungle is an animate being and its animals are his fellow travellers in this world. His younger daughter, Hinnihami, breastfeeds a fawn. His sustainable living with fellow animals and nature is challenged by British law. He kills two people who try to dominate and suppress poor villagers by using their administerial powers. He is sentenced to death.

What I want to highlight here is the way our predecessors coexisted with nature and how they made the environment a part of their lives. Silindu’s philosophy of nature and animals is fascinating because he does not think that humans are not the centre of this living environment. Rather humans are a part of the whole ecosystem. This is the thinking that we need today to address the major environmental crises we are facing.

When I first addressed Aesthetica, the International conference on Performing Arts, as a keynote speaker, at Christ University, Bangalore, in 2018, in my keynote address, I emphasised the importance of understanding the human body, particularly the performing body as an embodied subject. What I meant by this term ‘embodied subject’ is that over the centuries, our bodies in theatre, rehearsal spaces and studios are being defined and described as an object to be manipulated. Even in modern dance, such manipulation is visible in the modernist approaches to dance. The human body is an object to be manipulated. However, I tried to show the audience that the performing body was not a mere object on stage for audience appreciation. It is a being that is vital for the phenomenological understanding of performance. The paradox of this objectification is that we objectify our bodies as something detached from the mind and similarly, we assume our environment, the world as something given for human consumption.

Performance and Sustainability

Just to bring the phenomenological lexicon to this discussion, I will draw your attention to one of the chapter in my latest book, titled, Lamp in a Windless Place: Phenomenology and Performance (2025) published by VAPA Press, University of Visual and Performing Arts, Colombo. This project is based on Sarah Kane’s famous play text 4.48 Psychosis. In this chapter I wrote phenomenological environmentalists explain the two ways that human beings interact and engage with the life-world. The one way of this engagement is defined as ‘involvement’ we involve with various activities in the world and it is one of the ways that we are being-in-the-world. The second way of being-in-this-world is that we ‘inhere’ in the world meaning that we are built with worldly phenomena or we are made out of the same stuff of our environment. (James cited in Liyanage 2025, pp. 98-99). This coupling and encroachment between our bodies and the environment occur mostly without our conscious interference. Yet, the problem with our human activities, and also our artistic practices is that we see our environment (human body) as an object to be consumed and manipulated.

Today, it is more important for us to change our mindsets to rethink our daily practices of performing arts and understand how human, nature, space and non-human species are vital for our existence in this world. Sustainable discourse comes into play with the United Nations initiative to make humans understand the major crises we are facing. In 2016, 195 parties agreed to follow the treaty of the Paris Agreement, which is mainly focused on climate change and the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels. Major scientists are talking about the ‘tipping points’. Tipping points indicate the current crisis that humans and other-than humans are going to face in the coming years.

Among those sustainable goals, the most important and the urgent point to be focused seems to be the climate emergency. Leading scientists of environmental sciences have already warned that within a few years, global warming will increase up to the level that the consequences will be catastrophic and dangerous to all, human and non-human. Ice sheets are shrinking; sea water level is increasing, and coral reefs are dying. It is becoming increasingly evident that countries in our region, particularly in South Asia, have been experiencing major climate shifts over the past few decades. Recent Cyclone Ditwah and the catastrophic flood devastated parts of not only Sri Lanka but also Malaysia, Sumatra, India, etc. Professor Missaka Hettiarachchi and Devki Perera published a landmark book, titled Nature – based method for water resource management (2025). In this work Hettiarachchi and Perera clearly argue that flood, erosion, and landslides are a part of the geological evolution and transformations. They are inherent activities in nature, which form new landscapes and conditions in natural environments. But the problem is that we experience these natural events frequently and they abruptly occur in response to human-nature collisions.

Climate Emergency

Professor Jeffry Sachs stresses the importance of taking action to prevent future climatic change. For him, we are facing three mega environmental crises: 1. Climate crisis leading to greenhouse gas emission due to fossil fuel burning. We have already come to the 1.5 warming limit now. He predicts that humans will experience 2.0 degree Celsius within two decades. 2. Second is the ecological crisis. This is the destruction of rainforests in South East Asia, Amazon and other regions. He argues that Amazon has reached the tipping point, meaning that the rain forest is in danger and it would be a dry land in a few decades time. Because of ocean acidification, scientists have already warned that we are in the wake of the destruction of coral reefs. The process is that high carbon dioxide dissolves in the water and it creates the carbonic acid. It causes the destruction of the coral reef system. 3. The third ecological crisis is the mega pollution. Our environment is already polluted with toxic chemicals, our waterways, ocean, soil, air and food chains are polluted. Micro plastics are already in our blood streams, in our lungs and even in our fetuses to be born.

The climate crisis is not just a natural catastrophe; it is political in many ways. Greenhouse gas emission is still continuing, and the developed countries such as the United States of America, Canada, China and Germany produce more carbon than the countries in the periphery. As Sachs rightly argues, the US politics is manipulated by the biggest oil companies in the world and President Trump is an agent of such multinational companies whose intention is to accumulate wealth through oil burning. Very recently, the US invaded Venezuela not to restore democracy but to gain access to the largest oil reserves in the country. We have seen many wars, led by the US, due to greed for wealth and natural resources. The US has withdrawn from the Paris agreement. President Trump calls climate change a hoax! So, the world’s current political situation is directly linked to the future of our environment, our resources and climate change.

Anthropocentrism in Performance

Back to creative arts. In the modernist era of our artistic practices and culture, we mimicked and replicated proscenium theatre inherited from Europe and elsewhere and revolutionised the ways that we see performance and perceiving. Our traditional modes of performance practices were replaced by the modern technology, architectural structures, studio training methods and techniques. Today, we can look back and see whether these creative arts practices have been sustainable with the larger human catastrophes that we experience almost daily. Eddie Patterson and Dr. Lara Stevenson have recently published an important and influential book, titled Performing Climate (2025). Being performance studies scholars, Patterson and Stevenson’s book contains 14 chapters interconnected and explores the human and non-human or more than human elements in the world. Patterson and Stevenson write that ‘performance is a messy business; a bloody mess’. ‘Performance is a mess of matter, climate, things, actors, and affects: neither a dramatic or postdramatic theatre but a network of dramaturgical elements; a site of birth and death, decay and renewal’ (Patterson and Stevenson, 2025, p. 1). In this book, they further explore the new ways of reading performance, making performance and perceiving performance. They argue that ‘we are interested in analyzing performance not as an insulated, exclusive art form predicated on human centrality but as a process that celebrates the transformative properties of waste – bacteria, debris and breakdown – composting and mulching within a larger network of bacteria, fungi and microbes embedded in the skin, air, soil and interacting with cellular networks and atmospheric conditions’ (ibid).

Our modern theatre has always been anthropocentric. Even in Sri Lanka, the father of modern Sinhala theatre, Professor Ediriweera Sarachchandra adapted traditional dance drama and developed a modern theatre for middle class theatregoers. This modern theatre was anthropogenic, patriarchal and marginalised the subaltern groups such as women, non-human beings, environment and so forth. The traditional dance and dramas, nadagam and kooththu were much more embedded in rituals performed by communities for various social, cultural and spiritual purposes were uprooted and established in the proscenium theatre for the audience, whose aesthetic buds were trained and sustained by the colonial theatre and criticism. Even traditional dance was uprooted from its traditional setting embedded in the ecosystem and placed on the proscenium theatre for the sake of modernisation of dance for the modern theatregoers. A new group of spectators, theatregoers, were produced to watch those performances which took place in city theatre buildings, insulated architectural spaces where the black boxes were lit up with expensive lighting technology and air-conditioning. As Patterson and Stevenson argue, the Western theatre has been obsessed with the human drama or autobiography. This western history of theatre has been ‘blind to the non-human agency and the natural world has always been in the background to the human centred stories’ (Patterson and Stevenson 2025).

Carbon Emission theatre

The performance practice that we have inherited and is continuing even today is highly problematic in the ways that we centre human agency over the non-human and the environment. This anthropocentric performance practice, as German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk called it, is ‘biospherical’. The biospherical theatre sees human action in the artificially constructed atmospheres for artistic innovations (Patterson and Stevenson 2025). Biospherical theatre is proto-laboratories and human greenhouses – in which able-bodied actors are trained and perform within air-conditioned black boxes; or more tellingly white people in white cubes’ (ibid).

Patterson and Stevenson further assert that ‘biospherical theatre is an enclosed Western form it is labour intensive, carbon intensive, hierarchical, exclusive, inaccessible extractive rather than generative of new knowledge and different ways of being with the world (ibid, p. 10). We inherited this hierarchical, exclusive, and carbon-oriented performance space from our past; as a colonial heritage. This colonial heritage of labour intensive, carbon intensive theatre is the major practice of performance in our societies. I am currently the Chairman of the National Theatre Sub-Committee under the purview of the Arts Council of Sri Lanka. Theatre practitioners today in Colombo are highly critical of the Ministry of Cultural Affairs for not having quality enclosed theatres in major cities in the country. They do not see the problems pertaining to the performance practice that is not ecologically sustainable for island nations like us.

We are possessed with the model of Globe theatre, which has been the model for theatre and entertainment in our regions for centuries now. However, today, we are forced to revisit and rethink this model of Globe theatre in the wake of the climate emergency. Patterson and Stevenson remind us that ‘inside these globes, art develops in enclosed and air-conditioned bubbles (laboratories, rehearsal rooms, conservatories, and galleries). This kind of theatre is biospherical: a human centric endeavour, evolving inside the globe, largely upholding the fantasy of itself as disconnected from atmospheric and environmental interactions beyond the human’ (Patterson and Stevenson 2025, p. 16).

Conclusion

According to Jim Bendell, it is not enough for us to develop resilience towards the climatic emergency; we need to embrace relinquishment (Stevenson, 2020, p. 89). It is the letting go of certain assets, behaviours and beliefs. Grotowski articulated this concept many decades back in his actor training at the Polish theatre laboratory. Grotowski developed the idea of via negative, letting go, or elimination for actors. Letting go of all the acculturations as Eugenio Barba articulates, to tap into the pure impulses and action. Grotowski even rejected the audience participation in his later works, para theatre, like Antonin Artaud, who rebelled against the dialogic, bourgeoisie theatre in France at the time. So, the modernist theatre directors have shown us that the Globe theatre is no longer a sustainable pathway for performance practice. It is time for us to rethink the carbon intensive, labour intensive, hierarchical, exclusive, and class-oriented theatre and performance.

References

Hettiarachchi, M., & Perera, D. (2025). Nature-Based Methods for Water Resources Engineering. The Institution of Engineers, Sri Lanka.

India Today Global. (2025, September 24). “U.S. government is in an open war against the Sustainable Development Goals”: Jeffrey Sachs. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qb4Jpqq4wvE

James, S. P. (2009). The Presence of Nature A Study in Phenomenology and Environmental Philosophy. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN IK.

Liyanage, S. (2025). Lamp in a Windless Place: Phenomenology and Performance. VAPA Press. (Original work published 2025)

SDSN. (2024, October 11). Sustainability Fundamentals with Jeffrey Sachs. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dJR0Q8ueQpc

Stevens, L. (2019). Anthroposcenic Performance and the Need For ‘Deep Dramaturgy’. Performance Research, 24(8), 89-97.

Stevens, L., & Varney, D. (2022). The Climate Siren: Hanna Cormick’s The Mermaid. TDR, 66(3), 107-118.

Woolf, L. (2012). The village in the jungle. Forgotten Books.

Author wishes to thank Himansi Dehigama for proofreading this manuscript.

Professor Saumya Liyanage is a professor of Drama and Theatre Currently working at the Department of Theatre Ballet and Modern Dance, Faculty of Dance and Drama, University of the Visual and Performing Arts, Colombo. He is the chairman of the State Theatre Subcommittee.

by Saumya Liyanage

Midweek Review

Islander Unbound

The pomp and pageantry of just a few hours,

Is not for him on this day in February,

When he’s been asked to think of things lofty,

Such as that he is the sole master of his destiny,

And that he’s well on track to self-sufficiency,

Rather, it’s time for that care-free feeling,

A time to zero in on the best of clothing,

Go for a carouse on the golden beaches,

And round-up pals for a cheering evening.

By Lynn Ockersz

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoMy experience in turning around the Merchant Bank of Sri Lanka (MBSL) – Episode 3

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoZone24x7 enters 2026 with strong momentum, reinforcing its role as an enterprise AI and automation partner

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoRemotely conducted Business Forum in Paris attracts reputed French companies

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoFour runs, a thousand dreams: How a small-town school bowled its way into the record books

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoComBank and Hayleys Mobility redefine sustainable mobility with flexible leasing solutions

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoAutodoc 360 relocates to reinforce commitment to premium auto care

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoHNB recognized among Top 10 Best Employers of 2025 at the EFC National Best Employer Awards

-

Midweek Review2 days ago

Midweek Review2 days agoA question of national pride