Features

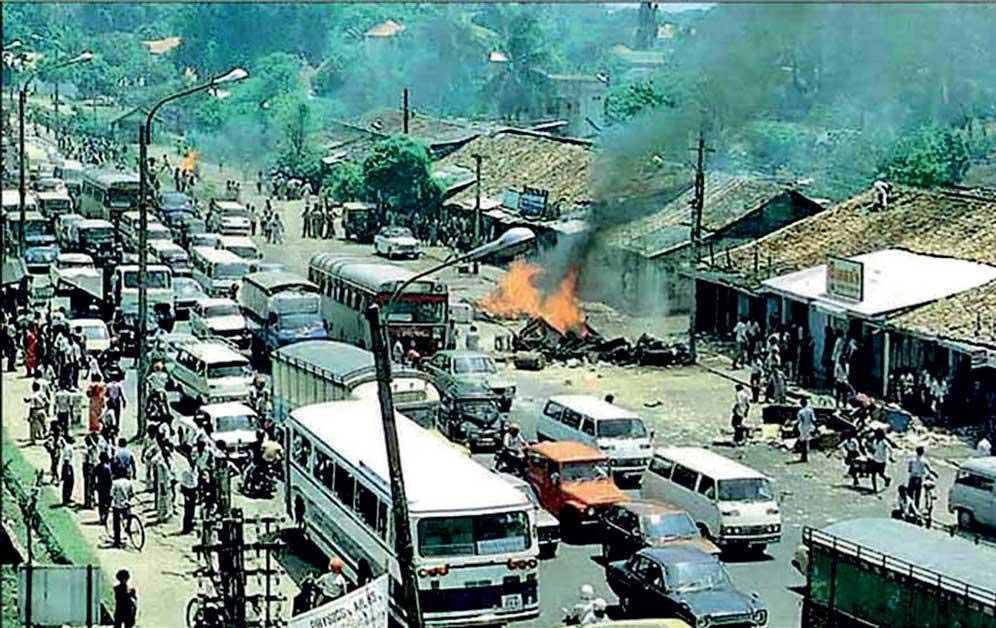

Black July– Pogrom and Survivors

by Jayantha Perera

It was an ordinary Monday morning. At the Lunawa railway station, I watched the calm blue sea dotted with a few fishing boats. The train to Colombo was 30 minutes late, and it was almost empty. I saw some confusion among railway passengers — some got off the train and got into a train that went to Kalutara. A friend among them warned me that I should not go to Colombo. When I reached the ARTI in Colombo 7, I had the eerie feeling that something was wrong. I saw some employees hurriedly leaving the ARTI. One told me that the Institute had received an anonymous telephone call that the LTTE had plans to attack Colombo before noon. I brushed off the rumour and went to my room.

I saw a Tamil colleague sobbing in her room. She told me that a mob had attacked her house in Wellawatte. The Police had taken her mother to a refugee camp. The director requested that I take my colleague to the refugee camp where her mother was. A driver, who was an ex-soldier, agreed to take us to the camp.

We realised the gravity of the security situation when we left the ARTI for the refugee camp. Hundreds of people, mostly office workers, were stranded on the road. People were walking home. Two soldiers checked our identity cards and my colleague’s handbag at the refugee camp. One asked me in Sinhala, “Why do you accompany a Tamil woman?” He told me politely that I should have sent her by herself without exposing myself to mobs. While we were waiting for the approval to enter the camp, a large crowd appeared from nowhere, shouting, “Kill the Tamils before they kill us! Some carried jerrycans full of petrol, iron clubs, and axes. They were in a frenzy. The soldiers at the camp gate stopped them before they reached the periphery wall of the school.

I introduced my colleague and myself to the Army officer at the registration desk as Deputy Directors of the ARTI. I told him my colleague had heard that her mother was already in the camp. He promised to find her whereabouts. When I left the camp, my colleague waved at me with tears in her eyes. I waited until she disappeared among the new refugees who were agitated and scared. Several women were crying, as they did not know what had happened to their children who went to work in the morning. Chaos, fear, hatred, and confusion reigned in the camp and its vicinity. It occurred to me that I had not offered to bring food or clothes for my colleague and her mother. I felt ashamed of myself.

The driver dropped me off at Bambalapitiya Junction on Galle Road. At the Bambalapitiya junction, I met two colleagues. We started walking towards Dehiwela, where we saw mobs searching for Tamils. A few stopped pedestrians and demanded to prove they were not Tamils. Suddenly, a convoy of cars and motorbicycles drove past us. Motorcycle riders shouted the LTTE had captured Colombo and the LTTE would kill us soon. A few minutes later, another convoy of vehicles passed us with the same message. Pedestrians ran to its side lanes, emptying the main road for about ten minutes.

At Dehiwela, we saw many men in their shorts and folded sarongs shouting the Sinhalese would kill the Tamils. Two men had lists of residents in the area and wanted to know their whereabouts. One mob got petrol by force from a gas station. We watched helplessly while mobs looted and demolished shops. At one shop, they grabbed the owner and assaulted him ruthlessly on the main road. He ran back to his shop with blood dripping from his head. I could not see the Army or Police on the road. Anarchy ruled, and many lost their lives and property in a few minutes.

I reached home exhausted and confused. I felt ashamed of myself because I could not help the people who were crying for help. The three young girls who ran along the Galle Road shouting for help had shaken me to my core. Without lunch, I slept. About an hour later, a jeep stopped in front of my house. The ARTI Director wanted me to go to the Ministry Head Office. I reached Colombo in 20 minutes, as the road was empty. The Army and the Air Force had taken control of the Galle Road. There were no mobs or fleeing people. But I could see the smoke rising from the burned houses, shops, and factories.

The Secretary of the Ministry of Agriculture and Lands presided over the meeting. The Secretary informed the meeting that the ministry would manage two refugee camps for a week or two. He wanted me to be at the refugee camp at St. Thomas’ College in Mount Lavinia. He explained that as many as 1,000 persons might seek refuge at the camp. My responsibilities were to feed them and provide bedding, drinking water, and sanitary facilities. The Secretary also told me that I should get the Army’s assistance and ask the Cooperative Wholesale Establishment (CWE) to get dry food to the camp. He signed several papers that authorised me to order and accept food, bedding, sanitary items, drinking water, blankets, plates, and glasses. He also assigned three Ministry officials to work at the camp.

Hundreds of adults and children were at St. Thomas’ College. Some were crying, others were shouting, and a few had bandaged heads and bloodstained arms. It was a chaotic situation. I told them, using a megaphone, that help would soon come, and the security forces would protect them. One laughed and asked, “Why do you want to help us. Aren’t you a Sinhalese?” I told him to be patient.

An old woman who lost her house told me a squad of goons had arrived at her place brandishing clubs and swords. They told her to get out of the house if she wanted to save her life. Another woman said that goons came with a list of names and checked each house on the lane for Tamil families before setting her home on fire. Families with small children and grown-up daughters had to save their children from mobs. Some parents pushed their daughters and sons over boundary walls to friends’ compounds to protect them from attackers before leaving their homes. Some of them did not know what had happened to their children.

My colleagues set up an office and recorded the refugees’ names and addresses. They also prepared an inventory of food, bedding, blankets, and sanitary facilities that we had received. NGOs, neighbourhood groups, and religious organisations already delivered food, essential medicine, and hygienic supplies. The camp received large quantities of rice, lentils, canned fish, onions, and bread. A benevolent donor sent more than 200 food parcels for dinner.

In the evening, I visited the ARTI Cafeteria Manager in Moratuwa. I asked him to find me six cooks and loan large cooking utensils. I promised to pay his charges within two weeks. His wife accompanied me to a small hamlet by the sea. There, she spoke to three middle-aged women and explained their new assignment. She asked them to collect three more women to go to St. Thomas’ College for a few days. I asked the Manager’s wife to pack basic spices, salt, and oil into one large cooking pot. The women had many years of experience cooking for many people at weddings and funerals.

Using the megaphone, I told the refugees that each family should find a place in a classroom or the large hall to sleep and collect bed sheets and mats from the camp office. A commotion erupted as some women did not want to sleep in rooms with strangers. Others were scared to sleep on the floor. After much discussion, we agreed to organise people into several clusters. ‘Neighbours,’ ‘children attending the same school,’ ‘professionals,’ and ‘government officials’ were some criteria for allocating camp space. Two large posters were hung on a wall showing men and women their toilets.

I rang a bell at 9 pm to indicate the dinner was ready. The food parcels we had received were sufficient to feed those who wanted to eat. Men and women lined up, and four cooks served food. Several young mothers requested milk for their toddlers. Fortunately, the storeroom had a few milk cartons and packets of milk powder. I asked them to prepare milk after dinner. Several older people did not eat rice at night and wanted bread. I checked the storeroom and found steamed bread received from India. I asked a cook to heat 25 small loaves of bread on a flat steel plate. I distributed the bread among those who preferred bread to rice.

It took about eight hours to settle the refugees in the camp and console them. I promised to check on their houses the following day. Many were urban poor who lived in small huts and rented dwellings in Dehiwela and Ratmalana. They had lost everything.

Several beggars who lived on the street had infiltrated the refugee camp after the Army chased them away from the pavements. It was difficult to distinguish them from the refugees. Security guards told me beggars were a security risk because they might steal whatever the refugees had with them, especially gold jewellery, or assault young women at night. The security guards could not check each entrant’s identity card because many had none.

After dinner, I thanked the cooks and allocated a place for them to sleep with bed sheets and mats. I discussed the breakfast with them and agreed to provide bread and pol sambal for adults and bread with eggs for children. Also, we decided to give each person a cup of tea.

I left the camp at 1 am. The road was empty, and the Army stopped me at two places. An army officer explained to me that the killing of 13 soldiers in the North and the delay in handing bodies to their families had triggered the riots. Looting and burning houses continued in lanes and slums. The Army did not have instructions to quell the riots and the mayhem. Instead, the Army controlled the main roads and arrested curfew breakers.

Before lunch, officials from the Commissioner General of Essential Services and the Ministry of Agriculture and Lands Secretary visited the camp with an Army Major. They talked to the refugees and noted their immediate concerns, such as withdrawing money from banks, contacting relatives, and getting medical attention. The Secretary spoke about the logistics and secured me two more vehicles with curfew passes. He told me to encourage refugees with friends or relatives nearby to move to such places as early as possible, as the riots were now under control. After they left, we served lunch of rice, dhal curry, and tempered potatoes. Many refugees told the kitchen crew that the food was good, though simple. More food, medicine, drinking water, and blankets arrived in the evening.

A Tamil colleague at the ARTI had become a refugee overnight. While fleeing, she went through a harrowing experience. Some shops from where she used to buy provisions were in flames. Mobs had attacked some people she knew in such shops after destroying shops and houses. Soon after she left home, a mob gathered in front of her house and checked the electoral list to identify the owners of houses in the lane. Fortunately, the list had the name of her father’s Sinhalese tenant. The mob spared her house.

One morning, I found a young girl at the camp crying. Her mother told me the girl’s 11th birthday was in two days. I asked her what she wanted. She said a birthday cake and her dollies. My colleagues promised to find a doll and to get a cake for her birthday.

We visited several bakeries in the area, but they were closed. We went to the Cafeteria Owner’s house in Moratuwa and begged his wife to bake a cake for the girl’s birthday. She listened to the little girl’s story and baked a large cake for her.

The girl’s mother lit a candle, and her friends sang ‘Happy Birthday’. For the first time, the girl smiled. But soon, she started crying, saying that she wanted her dollies. A colleague gave her a small doll. The girl said she had a similar doll and wanted to go home to play with her toys.

The most challenging request came from a group of older people. They complained they hate to mix with “low castes” and “uncouth” refugees, especially at mealtime. They found it repugnant to eat with them and share bathrooms. I asked them what they wanted me to do. They suggested segregating them from others and providing a separate sleeping area with a toilet. I told them I could not segregate people on a caste or class basis. I explained that the riots had ended and they should consider moving to their relatives and friends. It was the fifth day of the camp. They were unhappy but did not raise this issue again.

Many refugees wanted to leave the camp but were scared and confused. They also wanted to avoid burdening their relatives and friends. Some wanted to rebuild destroyed or damaged houses as fast as they could. They wanted to visit their homes and return to the camp. Several refugees told me that many affected families had already decided to sell their property and go to Jaffna or South India. A few wanted to seek political asylum in Western countries.

Parents with young children were worried about their education. Several girls asked me how to get their textbooks and exercise books from their destroyed houses. One girl told me her father could not buy books for her and her sister, as he had lost all his money. I patiently listened to them and took notes.

On the eighth day after the riots, the refugee camp was closed. Some refugees were overwhelmed by emotions and cried when they met friends and relatives at the school gate. The meetings were heart-rending, but I was happy that they were determined to restart their lives from scratch. My great worry, however, was the fate of the children. Some were traumatised and did not want to leave the camp, where they found some stability and care.

There were about 30 persons who wanted to stay longer at the camp. I told them the camp was no longer providing food. A few confessed that they were beggars who lived on the road or in abandoned buildings. At the refugee camp, they found a safe place with security, food, and basic facilities. A few of them were getting ready to restart, begging. One young man told me that beggars went through the worst form of aggression, torture, and hunger every day, and no one cared about their plight. He knew some refugees did not want to see them at the camp. But he said, “We, too, are human beings and deserve kindness and help.”

A few years later, a refugee family invited me to lunch at their new home. When the riots broke out their children were toddlers. They looked normal and happy. I wanted to know how they had restarted their lives after the riots, but I did not want to broach the subject on that happy occasion.

After lunch, I walked along a lane severely affected by riots. At two places, people recognised me. Some families had rebuilt their houses partially. Later, I met a businessman who told me that Tamils, who had money, left for India, Canada, and Australia. I do not know what happened to the wage workers, low-grade government servants, and, mainly, the garment factory workers I met at the refugee camp. They must have regained their everyday lives. I wish they had, but I do not know.

Features

Crucial test for religious and ethnic harmony in Bangladesh

Will the Bangladesh parliamentary election bring into being a government that will ensure ethnic and religious harmony in the country? This is the poser on the lips of peace-loving sections in Bangladesh and a principal concern of those outside who mean the country well.

Will the Bangladesh parliamentary election bring into being a government that will ensure ethnic and religious harmony in the country? This is the poser on the lips of peace-loving sections in Bangladesh and a principal concern of those outside who mean the country well.

The apprehensions are mainly on the part of religious and ethnic minorities. The parliamentary poll of February 12th is expected to bring into existence a government headed by the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and the Islamist oriented Jamaat-e-Islami party and this is where the rub is. If these parties win, will it be a case of Bangladesh sliding in the direction of a theocracy or a state where majoritarian chauvinism thrives?

Chief of the Jamaat, Shafiqur Rahman, who was interviewed by sections of the international media recently said that there is no need for minority groups in Bangladesh to have the above fears. He assured, essentially, that the state that will come into being will be equable and inclusive. May it be so, is likely to be the wish of those who cherish a tension-free Bangladesh.

The party that could have posed a challenge to the above parties, the Awami League Party of former Prime Minister Hasina Wased, is out of the running on account of a suspension that was imposed on it by the authorities and the mentioned majoritarian-oriented parties are expected to have it easy at the polls.

A positive that has emerged against the backdrop of the poll is that most ordinary people in Bangladesh, be they Muslim or Hindu, are for communal and religious harmony and it is hoped that this sentiment will strongly prevail, going ahead. Interestingly, most of them were of the view, when interviewed, that it was the politicians who sowed the seeds of discord in the country and this viewpoint is widely shared by publics all over the region in respect of the politicians of their countries.

Some sections of the Jamaat party were of the view that matters with regard to the orientation of governance are best left to the incoming parliament to decide on but such opinions will be cold comfort for minority groups. If the parliamentary majority comes to consist of hard line Islamists, for instance, there is nothing to prevent the country from going in for theocratic governance. Consequently, minority group fears over their safety and protection cannot be prevented from spreading.

Therefore, we come back to the question of just and fair governance and whether Bangladesh’s future rulers could ensure these essential conditions of democratic rule. The latter, it is hoped, will be sufficiently perceptive to ascertain that a Bangladesh rife with religious and ethnic tensions, and therefore unstable, would not be in the interests of Bangladesh and those of the region’s countries.

Unfortunately, politicians region-wide fall for the lure of ethnic, religious and linguistic chauvinism. This happens even in the case of politicians who claim to be democratic in orientation. This fate even befell Bangladesh’s Awami League Party, which claims to be democratic and socialist in general outlook.

We have it on the authority of Taslima Nasrin in her ground-breaking novel, ‘Lajja’, that the Awami Party was not of any substantial help to Bangladesh’s Hindus, for example, when violence was unleashed on them by sections of the majority community. In fact some elements in the Awami Party were found to be siding with the Hindus’ murderous persecutors. Such are the temptations of hard line majoritarianism.

In Sri Lanka’s past numerous have been the occasions when even self-professed Leftists and their parties have conveniently fallen in line with Southern nationalist groups with self-interest in mind. The present NPP government in Sri Lanka has been waxing lyrical about fostering national reconciliation and harmony but it is yet to prove its worthiness on this score in practice. The NPP government remains untested material.

As a first step towards national reconciliation it is hoped that Sri Lanka’s present rulers would learn the Tamil language and address the people of the North and East of the country in Tamil and not Sinhala, which most Tamil-speaking people do not understand. We earnestly await official language reforms which afford to Tamil the dignity it deserves.

An acid test awaits Bangladesh as well on the nation-building front. Not only must all forms of chauvinism be shunned by the incoming rulers but a secular, truly democratic Bangladesh awaits being licked into shape. All identity barriers among people need to be abolished and it is this process that is referred to as nation-building.

On the foreign policy frontier, a task of foremost importance for Bangladesh is the need to build bridges of amity with India. If pragmatism is to rule the roost in foreign policy formulation, Bangladesh would place priority to the overcoming of this challenge. The repatriation to Bangladesh of ex-Prime Minister Hasina could emerge as a steep hurdle to bilateral accord but sagacious diplomacy must be used by Bangladesh to get over the problem.

A reply to N.A. de S. Amaratunga

A response has been penned by N.A. de S. Amaratunga (please see p5 of ‘The Island’ of February 6th) to a previous column by me on ‘ India shaping-up as a Swing State’, published in this newspaper on January 29th , but I remain firmly convinced that India remains a foremost democracy and a Swing State in the making.

If the countries of South Asia are to effectively manage ‘murderous terrorism’, particularly of the separatist kind, then they would do well to adopt to the best of their ability a system of government that provides for power decentralization from the centre to the provinces or periphery, as the case may be. This system has stood India in good stead and ought to prove effective in all other states that have fears of disintegration.

Moreover, power decentralization ensures that all communities within a country enjoy some self-governing rights within an overall unitary governance framework. Such power-sharing is a hallmark of democratic governance.

Features

Celebrating Valentine’s Day …

Valentine’s Day is all about celebrating love, romance, and affection, and this is how some of our well-known personalities plan to celebrate Valentine’s Day – 14th February:

Valentine’s Day is all about celebrating love, romance, and affection, and this is how some of our well-known personalities plan to celebrate Valentine’s Day – 14th February:

Merlina Fernando (Singer)

Yes, it’s a special day for lovers all over the world and it’s even more special to me because 14th February is the birthday of my husband Suresh, who’s the lead guitarist of my band Mission.

We have planned to celebrate Valentine’s Day and his Birthday together and it will be a wonderful night as always.

We will be having our fans and close friends, on that night, with their loved ones at Highso – City Max hotel Dubai, from 9.00 pm onwards.

Lorensz Francke (Elvis Tribute Artiste)

On Valentine’s Day I will be performing a live concert at a Wealthy Senior Home for Men and Women, and their families will be attending, as well.

I will be performing live with romantic, iconic love songs and my song list would include ‘Can’t Help falling in Love’, ‘Love Me Tender’, ‘Burning Love’, ‘Are You Lonesome Tonight’, ‘The Wonder of You’ and ‘’It’s Now or Never’ to name a few.

To make Valentine’s Day extra special I will give the Home folks red satin scarfs.

Emma Shanaya (Singer)

I plan on spending the day of love with my girls, especially my best friend. I don’t have a romantic Valentine this year but I am thrilled to spend it with the girl that loves me through and through. I’ll be in Colombo and look forward to go to a cute cafe and spend some quality time with my childhood best friend Zulha.

JAYASRI

Emma-and-Maneeka

This Valentine’s Day the band JAYASRI we will be really busy; in the morning we will be landing in Sri Lanka, after our Oman Tour; then in the afternoon we are invited as Chief Guests at our Maris Stella College Sports Meet, Negombo, and late night we will be with LineOne band live in Karandeniya Open Air Down South. Everywhere we will be sharing LOVE with the mass crowds.

Kay Jay (Singer)

I will stay at home and cook a lovely meal for lunch, watch some movies, together with Sanjaya, and, maybe we go out for dinner and have a lovely time. Come to think of it, every day is Valentine’s Day for me with Sanjaya Alles.

Maneka Liyanage (Beauty Tips)

On this special day, I celebrate love by spending meaningful time with the people I cherish. I prepare food with love and share meals together, because food made with love brings hearts closer. I enjoy my leisure time with them — talking, laughing, sharing stories, understanding each other, and creating beautiful memories. My wish for this Valentine’s Day is a world without fighting — a world where we love one another like our own beloved, where we do not hurt others, even through a single word or action. Let us choose kindness, patience, and understanding in everything we do.

Janaka Palapathwala (Singer)

Janaka

Valentine’s Day should not be the only day we speak about love.

From the moment we are born into this world, we seek love, first through the very drop of our mother’s milk, then through the boundless care of our Mother and Father, and the embrace of family.

Love is everywhere. All living beings, even plants, respond in affection when they are loved.

As we grow, we learn to love, and to be loved. One day, that love inspires us to build a new family of our own.

Love has no beginning and no end. It flows through every stage of life, timeless, endless, and eternal.

Natasha Rathnayake (Singer)

We don’t have any special plans for Valentine’s Day. When you’ve been in love with the same person for over 25 years, you realise that love isn’t a performance reserved for one calendar date. My husband and I have never been big on public displays, or grand gestures, on 14th February. Our love is expressed quietly and consistently, in ordinary, uncelebrated moments.

With time, you learn that love isn’t about proving anything to the world or buying into a commercialised idea of romance—flowers that wilt, sweets that spike blood sugar, and gifts that impress briefly but add little real value. In today’s society, marketing often pushes the idea that love is proven by how much money you spend, and that buying things is treated as a sign of commitment.

Real love doesn’t need reminders or price tags. It lives in showing up every day, choosing each other on unromantic days, and nurturing the relationship intentionally and without an audience.

This isn’t a judgment on those who enjoy celebrating Valentine’s Day. It’s simply a personal choice.

Melloney Dassanayake (Miss Universe Sri Lanka 2024)

I truly believe it’s beautiful to have a day specially dedicated to love. But, for me, Valentine’s Day goes far beyond romantic love alone. It celebrates every form of love we hold close to our hearts: the love for family, friends, and that one special person who makes life brighter. While 14th February gives us a moment to pause and celebrate, I always remind myself that love should never be limited to just one day. Every single day should feel like Valentine’s Day – constant reminder to the people we love that they are never alone, that they are valued, and that they matter.

I truly believe it’s beautiful to have a day specially dedicated to love. But, for me, Valentine’s Day goes far beyond romantic love alone. It celebrates every form of love we hold close to our hearts: the love for family, friends, and that one special person who makes life brighter. While 14th February gives us a moment to pause and celebrate, I always remind myself that love should never be limited to just one day. Every single day should feel like Valentine’s Day – constant reminder to the people we love that they are never alone, that they are valued, and that they matter.

I’m incredibly blessed because, for me, every day feels like Valentine’s Day. My special person makes sure of that through the smallest gestures, the quiet moments, and the simple reminders that love lives in the details. He shows me that it’s the little things that count, and that love doesn’t need grand stages to feel extraordinary. This Valentine’s Day, perfection would be something intimate and meaningful: a cozy picnic in our home garden, surrounded by nature, laughter, and warmth, followed by an abstract drawing session where we let our creativity flow freely. To me, that’s what love is – simple, soulful, expressive, and deeply personal. When love is real, every ordinary moment becomes magical.

Noshin De Silva (Actress)

Valentine’s Day is one of my favourite holidays! I love the décor, the hearts everywhere, the pinks and reds, heart-shaped chocolates, and roses all around. But honestly, I believe every day can be Valentine’s Day.

It doesn’t have to be just about romantic love. It’s a chance to celebrate love in all its forms with friends, family, or even by taking a little time for yourself.

Whether you’re spending the day with someone special or enjoying your own company, it’s a reminder to appreciate meaningful connections, show kindness, and lead with love every day.

And yes, I’m fully on theme this year with heart nail art and heart mehendi design!

Wishing everyone a very happy Valentine’s Day, but, remember, love yourself first, and don’t forget to treat yourself.

Sending my love to all of you.

Features

Banana and Aloe Vera

To create a powerful, natural, and hydrating beauty mask that soothes inflammation, fights acne, and boosts skin radiance, mix a mashed banana with fresh aloe vera gel.

To create a powerful, natural, and hydrating beauty mask that soothes inflammation, fights acne, and boosts skin radiance, mix a mashed banana with fresh aloe vera gel.

This nutrient-rich blend acts as an antioxidant-packed anti-ageing treatment that also doubles as a nourishing, shiny hair mask.

* Face Masks for Glowing Skin:

Mix 01 ripe banana with 01 tablespoon of fresh aloe vera gel and apply this mixture to the face. Massage for a few minutes, leave for 15-20 minutes, and then rinse off for a glowing complexion.

* Acne and Soothing Mask:

Mix 01 tablespoon of fresh aloe vera gel with 1/2 a mashed banana and 01 teaspoon of honey. Apply this mixture to clean skin to calm inflammation, reduce redness, and hydrate dry, sensitive skin. Leave for 15-20 minutes, and rinse with warm water.

* Hair Treatment for Shine:

Mix 01 fresh ripe banana with 03 tablespoons of fresh aloe vera gel and 01 teaspoon of honey. Apply from scalp to ends, massage for 10-15 minutes and then let it dry for maximum absorption. Rinse thoroughly with cool water for soft, shiny, and frizz-free hair.

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoMy experience in turning around the Merchant Bank of Sri Lanka (MBSL) – Episode 3

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoZone24x7 enters 2026 with strong momentum, reinforcing its role as an enterprise AI and automation partner

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoRemotely conducted Business Forum in Paris attracts reputed French companies

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoFour runs, a thousand dreams: How a small-town school bowled its way into the record books

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoComBank and Hayleys Mobility redefine sustainable mobility with flexible leasing solutions

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoAutodoc 360 relocates to reinforce commitment to premium auto care

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoHNB recognized among Top 10 Best Employers of 2025 at the EFC National Best Employer Awards

-

Midweek Review2 days ago

Midweek Review2 days agoA question of national pride