Features

A senior cop remembers April 1971

(Excerpted from the memoirs of Senior DIG (Retd.) Edward Gunawardena)

A few months after the SLFP-led United Front Alliance headed by Mrs. Sirima Bandaranaike was elected in 1970, information started trickling in that the JVP was planning an uprising against the government. Cells were formed island-wide and clandestine indoctrination classes conducted by trained cadres. Simultaneously there was a spate of bank robberies and thefts of guns from households were reported to the police from all parts of the island. Unidentified youths were collecting empty cigarette and condensed milk tins, bottles, spent bulbs and cutting pieces of barbed wire from fences to make hand bombs and Molotov cocktails. Instances of bombs being tested even in the Peradeniya campus came to light.

By January 1971 the threat became real and the police began making arrests. Rohana Wijeweera, the leader of the movement, was arrested with an accomplice Kelly Senanayake at Amparai and detained at the Magazine prison. In the villages the common talk was that a ‘Che Guevera’ movement has started. Unknown youth moving about in villages were being referred to as ‘Che Gueveras.’ Police intelligence briefed the government of the developing ‘Naxalite’ like situation and action was taken to alert all police stations.

At the end of March 1971 there was specific information that the first targets would be the police stations. The attacks were to be carried out simultaneously on a particular day at a given time. With heightened police activity, the JVP ‘attack groups’ were pressurized to put their plan into effect hurriedly despite Wijeweera being incarcerated.

Synchronizing the attacks was a problem for the JVP. Mobile phones were not available then and the leaders had to resort to coded messages in newspapers. Police intelligence was able to crack their codes without much difficulty. It came to light that all police stations would come under attack at midnight on of April 5. The plan was to fire with guns at the station, and throw hand bombs and Molotov cocktails so that the policemen would run away or be killed. The attackers were to rush in and seize all the firearms in the stations.

The Police were ordered to be on full alert on this day. On April 4, in addition to my duties as the Director, Police Planning and Research I was acting for Mr. P. L. Munidasa, SP as the Personal Assistant to Mr.Stanley Senanayake the IGP. At about 4 p.m. an urgent radio message addressed to the IGP was opened by me. The message was alarming. The Wellawaya Police station had been attacked and the OIC Inspector Jayasekera had received gunshot injuries, a PC killed and several injured. The police had fought back bravely and not abandoned the station.

The Police were ordered to be on full alert on this day. On April 4, in addition to my duties as the Director, Police Planning and Research I was acting for Mr. P. L. Munidasa, SP as the Personal Assistant to Mr.Stanley Senanayake the IGP. At about 4 p.m. an urgent radio message addressed to the IGP was opened by me. The message was alarming. The Wellawaya Police station had been attacked and the OIC Inspector Jayasekera had received gunshot injuries, a PC killed and several injured. The police had fought back bravely and not abandoned the station.

As soon as the IGP was informed, he reacted calmly. He summoned all the senior officers present at Headquarters briefed them and ordered that all police stations including the Field Force Headquarters, the Training School and Police Headquarters itself be placed on full alert with immediate effect. Among the officers present I distinctly remember DIGs S.S. Joseph and T.B. Werapitiya. All police officers irrespective of rank were to be armed and issued with adequate ammunition. This task was entrusted to ASP M.D. Perera of Field Force Headquarters who was in charge of the armoury. I too was issued with a Sterling Sub-machine gun.

During this time I was living in Battaramulla with my wife and year old child in my father’s house. My brothers, Owen and Aelian, who were unmarried were also living there. My wife and I with the child occupied a fairly large room in which an official telephone had been installed. We had decided to live here as I had started building a house on the same ancestral property; and it is in this house that we have lived since 1971. 1 had an official car, a new Austin A40 which I drove as I had not been able to find a suitable police driver. Apart from the telephone, I had a walkie-talkie and was in constant communication with the Police Command Room and the IGP.

On the night of April 4 as there was nothing significant happening except for radio messages from police stations asking for additional strength, weapons and ammunition, I was permitted by the IGP to get back home. I telephoned the Welikada and Talangama police stations and was informed that the stations were being guarded and the areas were quiet. At about 10 p.m. I reached home safely and slept soundly. But something strange happened which to date remains a mystery. At about 3.30 a.m. (on the April 5) my telephone rang. The caller in a very authoritative voice said, “This is Capt. Gajanayake from Temple Trees, the Prime Minister wants you immediately.”

I hurriedly got into my uniform and woke up my wife and told her about the call. Just then it occurred to me that I should call Temple Trees. There was an operations room already functioning there and Mr. Felix Dias Bandaranaike had taken control of the situation. When I called, it was answered by my friend and colleague Mr. Cyril Herath. He assured me that I was not required at Temple Trees and that there was no person there by the name of Capt. Gajanayake. Much against the wishes of my wife, my father and brothers, dressed in a sarong and shirt and armed with my revolver I walked down the road for about half a kilometer. But there was none on the road at that time of the night.

By next night disturbing messages were coming to Police Headquarters from all over the Island. A large number of police stations had been attacked and police officers killed and injured. SP Navaratnam and Inspector Thomasz had been shot at on the road in Elpitiya and the latter had succumbed to the injuries. A number of Estate Superintendents had been shot dead. Trees were cut and electricity posts brought down. Desperate messages were pouring in from several Districts stating that administration had come to a standstill. The Kegalle, Kurunegala, Galle and Anuradhapura Districts were the worst affected. The least damage was in areas where the police had taken the offensive. In Colombo although the police stations were not attacked there was panic. With the possibility of water mains being damaged tube wells were hurriedly sunk at Temple Trees. General Attygalle, the Army Commander, had taken over the security of the Prime Minister and Temple Trees.

Talangama Police station that policed Battaramulla was guarded by the people of the area. Even my brothers spent the nights there armed with my father’s shotgun. IP Terrence Perera who was shot dead by the JVP in 1987 was the OIC. The excellent reputation he had in the area made ordinary folk flock to the station and take up positions to defend it if it was attacked. Some of the people of Battaramulla who were regularly there whose names I can remember and who are still living are K.C. Perera, W.A.C. Perera, Jayasiri, Victor Henry, Lionel Caldera and P.P. de Silva among others. Incidentally Brigadier Prasanna de Silva one of the heroes of the recently concluded war against the LTTE is a son of P.P. de Silva.

There were also those who gave assistance in the form of food and drink for all those who had gone to the aid of the police. The late Edward Rupasinghe a prominent businessman of Battaramulla, supplied large quantities of bread and short eats from the Westown Bakery which he owned. However as the attacks on police stations and state property became more and more intense, the SP Nugegoda T.S. Bongso decided to close down the Talangama Police Station and withdraw all the officers to the Mirihana Headquarters Station. This move made it unsafe for me to live in Battaramulla and travel to Police Headquarters.

The late Mr. Tiny Seneviratne SP and his charming wife readily accommodated us in their official quarters at Keppetipola Mawatha. The late Mr. K.B. Ratnayake had also left his Anuradhapura residence to live with the Seneviratnes. KBR and Tiny were good friends. During this time in the midst of all the disheartening news from all directions there were a few bright spots I have not forgotten. These were messages from Amparai, Kurunegala and Mawanella.

At Amparai the ASP in charge A.S. Seneviratne on information received that a busload of armed insurgents were on the way to attack the police station in broad daylight had hurriedly evacuated the station and got men with arms to hide behind trees and bushes having placed a few dummy policemen near the reserve table that was visible as one entered the station. As the busload of insurgents turned into the police station premises a hail of gunfire had been directed at it. About 20 insurgents had been killed and the bus set ablaze.

In Kurunegala the Pothuhera police station had been overrun and occupied by insurgents. Mr. Leo Perera who was ASP Kurunegala had approached the station with a party in mufti unnoticed by the insurgents, taken them by surprise and shot six of them dead. The police station had been reestablished immediately after.

In Mawanella and Aranayake the insurgents held complete sway. Two youths had visited the house of a retired school master on the outskirts of Mawanella town and demanded his gun. He had gone in, and loaded his double barrel gun and come out on the pretext of handing it over to the two youths he had shot them both dead discharging both barrels. The schoolmaster and his family had taken their belongings, got into a lorry and immediately left the area.

With the joint operations Room at Temple Trees under Minister Felix Dias Bandaranaike assisted by the Service Chiefs, the IGP and several senior public servants functioning fully the offensive against the insurgents began to work successfully. Units from the Army, Navy and the Air Force were actively assisting the police in all parts of the Island particularly in making arrests. Helicopters with pilots provided by India and Pakistan were being extensively used by officials and senior officers of the Armed Services and the Police for urgent travel.

On the night of April 10 or 11, I had finished my work at Police Headquarters and returned at about 10 p.m. to Keppetipola Mawatha. During the day my wife had been able to find a police jeep to be sent to Battaramulla to fetch a substantial supply of jak fruits, manioc and coconuts from our garden. The Seneviratnes took immense pleasure in feeding all and sundry who visited their home.

At about 10 p.m. I received a call from the IGP requesting me to take over Kurunegala Division the following morning. He told me that a helicopter would be ready for me at Parsons Road Air Force Grounds at 5.30 a.m. According to him the insurgents were still active in the area; the SP Mr. A. Mahendran was on sick leave and Mr. Leo Perera ASP was bravely handling the situation almost single handed. Although the assignment did not bother me much, my wife was noticeably concerned. Mrs. Seneviratne an ardent Catholic gave me a miniature medal of St. Anthony assuring me that the Saint will protect me from harm.

The helicopter took off at the crack of dawn. It was piloted by a young Flt.. Lieutenant from the SLAF and I was the only passenger. I have forgotten the name of this pilot. He was a pleasant guy who kept conversing with me all the way. He told me that he had flown to Anuradhapura and Deniyaya the previous day and in both those areas the insurgents were on the run and the security forces were on top.

Having been cloistered at Police Headquarters always peeking out of windows with a weapon in the ready or reading messages of deaths of police officers and the successes of insurgents, a feeling of relief overtook me on the flight. In fact I began to look forward to some action and this did not take long to come.

As the helicopter landed I was met by ASP Leo Perera who was a contemporary of mine at Peradeniya. There were several other police officers and also two officers of the Air Force. The latter were there to go to Colombo in the same aircraft. I carried only a travel bag with the minimum of clothes.

My first task was to address the officers gathered at the Police Station. I praised them for facing the situation bravely. Their only complaint was that they were short of ammunition. I suggested to Leo that as far as possible shotguns be used instead of 303 rifles. An officer was dispatched immediately to get as many guns as possible from the Kachcheri and the production room of the court house.

ASP M.D. Perera of Field Force Headquarters who was contacted on radio undertook to airlift 15 boxes of SG and No. four 12-bore cartridges. All the officers present were pleased as they all agreed that shotguns were more effective. The families of police officers too had left their quarters and barracks and taken up residence in different sections of the station. Most importantly their morale was high. Leo Perera had led them admirably.

At about 10 a.m. after partaking of a kiribath and lunumiris breakfast with the men I left for my office, that of the SP Kurunegala. I was very happy when Inspector Subramaniam was assigned to me. He was known to me and he appeared to be pleased with the task. He was a loyal and cheerful type. I chose a Land Rover with a removable canvas top for my use and also a sergeant and two constables with rifles. Subramaniam and I had Sterling sub-machine guns. These officers were to be with me at all times. In the afternoon I was able to obtain two double barrel Webley & Scott shotguns with about 10 No. four cartridges. There were several beds also already in place in the office. Telephoning my wife was no problem as I enjoyed the privilege of priority calls.

I had lunch with Inspector Subramaniam and my escort in the office. The rice and curry lunch had been sent from the Police Station mess. After a late lunch and a brief post lunch rest the four of us dressed in mufti set off in the Land Rover driven by a police driver. IP Subramaniam carried a Stirling sub-machine gun and the sergeant and PC 303 rifles. A loaded double barrel gun lay on the floor board of the Land Rover. After visiting the Potuhera and Mawathagama stations and patrolling the town area we returned to our base. Subramaniam also made arrangements with a boutique in town for some egg hoppers to be delivered to us at 8 p.m.

A little excitement was to come soon. After refreshing ourselves and having eaten the egg hoppers we visited the station. At about 9.45 p.m. I was having a discussion with a few officers in the office of the OIC Crimes when we heard two minor explosions and somebody screaming that the station was being attacked. Armed officers took up positions according to instructions. I ordered that the station lights be put off. An Inspector armed with a loaded shotgun, a few constables and I crawled to the rear of the building. Bombs were being thrown from the direction of a clump of plantain trees. A small tin with the fuse still burning fell close to where we were.

A PC jumped forward and doused the fuse throwing a wet gunny bag on the object. Two more similar objects fell thrown from the same direction. The same PC rushed forward and removed the burning fuses with his hands. As the objects were coming from about the identical place, I grabbed the shotgun and discharged both barrels in that direction simultaneously. The ‘bombing’ stopped thereafter. Two armed mobile patrols were sent out to the roads to look for any suspects. But the roads were empty. At about 11 p.m. the lights were put on and the station resumed its activities.

To say the least these ‘bombs’ were crude and primitive. In each of these we found a large ‘batta’ cracker the fuse of which came out of a hole in the lid of a cigarette tin. Round the ‘batta’ was a layer of tightly compressed fibres akin to the fibres in a squirrels nest. On the outer side of the compressed fibre were barbs cut off barbed wire and rusted nails. A thousand of such ‘bombs’ could not have matched the destructive force of a modern hand grenade. This state of unpreparedness was perhaps the foremost reason why the insurrection fizzled out early.

More action was to follow that same night. After my escort of three officers and I had retired to bed in the SP’s office, a few minutes after midnight the Sergeant guarding a large transformer on the Wariyapola Road with two other constables started calling me on the walkie talkie in a desperate tone. He sounded very excited and told me that shots were being heard close to the guard point. I instructed him to take up position a reasonable distance away from the transformer where there were no lights and shoot at sight any person or persons approaching the transformer. I also assured him that I would be at the guard post with an armed party in the quickest possible time.

IP Subramaniam and the other two officers were eager to join me. I got the driver to remove the hood cloth of the Land Rover. Whilst the sergeant who was armed with a rifle occupied the front seat alongside the driver, Subramaniam and I armed with two double barrel guns loaded with No. four cartridges took up a standing position with the guns resting on the first bar of the hood. The two PCs were to observe either side of the road. Prior to leaving I radioed the Police station to inform the Airforce operations room about my movements and not to have any foot patrols in the vicinity of the transformer.

There were no vehicles or any pedestrians on the way to the transformer. About a hundred meters to go we noticed a group of about eight to 10 dressed in shorts getting on to the road from the shrub. The distance was about 50 to 75 meters. The driver instinctively slowed down. The shining butts of two to three guns made us react instantly. I whispered to Subramaniam when I say ‘Fire’ to pull both triggers one after the other. We fired simultaneously and the Sergeant and PCs also fired their rifles.

Once the smoke cleared we noticed that the group had vanished.

As we approached the spot with the headlights on we noticed three shot guns scattered about the place. On closer examination there was blood all over and a man lay fallen groaning in pain. Beside him was a cloth bag which contained six cigarette tin hand bombs. Two live cartridges were also found. In two of the guns the spent cartridges were stuck as the ejectors were not working. The other gun was loaded with a ball cartridge which had not been fired. Having collected the guns, the bag containing the bombs and some rubber slippers that had been left behind. We proceeded on our mission to the transformer having radioed the guard Sergeant that we were close by.

As we approached the transformer the Guard Sergeant and the 2 PCs came out of the darkness to greet us. They were visibly relieved. But when the Sergeant told us that several shots were heard even 15 minutes before we arrived, I explained to them what had happened on the way. The Sergeant’s immediate response was, “They must be the rascals who were hovering about the village. They are some rowdies from outside this area who are pretending to be Che Guevaras”.

After reassuring them we left. On the way we stopped at the place where the shooting occurred. The man who was on the ground groaning in pain was not there.

Having snatched a couple of hours of sleep, at about 9 a.m. I drove with the escort to the Kurunegala Convent to call on the Co-ordinating officer Wing Commander Weeratne. A charming man, he received me cordially. He looked completely relaxed, dressed only in a shirt and sarong. He introduced me to several other senior officers of the Airforce and Army who were billeted in that spacious rectangular hall. One of the officers to whom I was introduced was Major Tony Gabriel the eminent cancer surgeon. A volunteer, he had been mobilized. I was also told that a bed was reserved for me. But I politely told him that I preferred to operate from my office. Wing Commander Weeratne also told me that he would be leaving to Colombo on the following day and the arrangement approved by Temple Trees was for the SP to act whenever the Co-ordinating officer was out of Kurunegala.

I joined the Co-ordinating officer and others at breakfast – string hoppers, kirihodi and pol sambol and left for the Police Station soon after. The escort was also well looked after. Weeratne and Tony Gabriel became good friends of mine. Sadly they are both not among the living today. After the meeting with the Co-ordinating officer we visited the Potuhera Police Station. Blood stains were clearly visible still and the walls and furniture were riddled with bullet and pellet marks. The officers looked cheerful and well settled. They were all full of praise for the exemplary courage shown by ASP Leo Perera in destroying the insurgents and other riffraff who were occupying the station and for re-establishing it quickly. One officer even went to the extent of suggesting that a brass plaque be installed mentioning the feat of Mr. Leo Perera.

When we returned to Kurunegala the officers were having lunch at the Station. The time was about 1.30 p.m. We too joined. Leo Perera was also there. He had tried several times to look me up but had failed. I complimented him for the excellent work done and told him that the high morale of the Kurunegala police was solely due to his leadership. He smiled in acknowledgment. But I noticed that he was not all that happy. He had a worried look on his face.

At about this time a serious incident had taken place giving the indication that insurgents were still active in the area. An Aiforce platoon (flight) on a recce in the outskirts of the town had come across a group of insurgents in a wooded area. The surprised group had surrendered with a few shot guns. An airman noticing one stray insurgent who was taking cover behind a bush had challenged him to surrender. The insurgent had instantly fired a shot at the airman who had dropped dead. The attacker had been shot dead in return by another airman.

At about 3 p.m. an Airforce vehicle drew up at the police station with a load of nine young men who had been arrested. They had deposited the two dead bodies at the hospital mortuary. All those under arrest were boys in their teens dressed in blue shorts and shirts. They had all been badly beaten up. I cautioned the airmen not to beat them further and took them into police custody. They had bleeding wounds which were washed and attended to by several policemen as they were all innocent looking children.

On questioning they confessed that they were retreating from the Warakapola area and their destination was the Ritigala jungles in Anuradhapura. They had these instructions from their high command. At this time, as if from nowhere appeared two young foreign journalists, a man and a woman. One was from the Washington Post and the other, the young woman from the Christian Science Monitor. Apart from taking photographs they too asked various questions.

The boys had their mouths and teeth were badly stained. They had been chewing tender leaves to get over their hunger. According to them they had been taught various ways to survive in the jungle. They had been told to eat apart from fruits and berries and tender leaves even creatures such as lizards and snakes; and insects particularly termites and earthworms. The nine young men were provided bathing facilities and a meal of buns and plantains; and locked up with about five more insurgent suspects to be sent to the rehabilitation camp that had been established at the Sri Jayawardenapura University premises. This was to be done on the following day in a hired van under a police escort.

At the police station I received a call from the Wariyapola police to say that six young men with gunshot injuries had got admitted to the Wariyapola hospital. They had told the police that they had been shot by a group of insurgents on the Wariyapola-Kurunegala road and had been able to reach the hospital in the trailer of a hand tractor. I immediately guessed that they could be the insurgents who were shot near the transformer. I explained to the OIC Wariyapola that they were a group of insurgents and to keep them in police custody.

In the evening I received a call from the IGP that he would be arriving in Kurunegala at 8 a.m. accompanied by General Attygalle. He told me that they wanted to have a chat with Leo Perera. I immediately informed Leo and told him to remain in office or at the Police Station in the morning.

By that time I had come to know that several Kurunegala SLFP lawyers had made some serious complaints against the ASP. Leo having received credible information that some of these lawyers were in league with insurgent leaders had not only questioned and cautioned them but even got their houses searched. One special reason for these lawyers to be aggrieved was because three of the insurgents shot dead by Leo when he recaptured the Potuhera Police Station had been local criminals who had been associating closely with them.

When the IGP arrived with the General I met them and brought them to my office. Wing Commander Weeratne, the Co-ordinating officer was also present to meet them. He had made arrangements for an armed escort of airmen to accompany the IGP and the General wherever they went. The undisclosed mission of the two top men was to take Leo back to Colombo with them. The IGP had been pressurized by Minister Felix Dias Bandaranaike to transfer the ASP, but the IGP had decided not to displease and discourage a young officer by making him feel that he had been punished. The IGP was more than conscious of the fact that the ASP had done an excellent job in quelling the insurgency in the Kurunegala District.

Leo was in my office. He was cheerful, calm and collected. The IGP and General Attygalle spoke to him cordially. Over a cup of tea the four of us discussed the happenings in the country. After a few minutes the General turned to Leo and said, “Leo, you have been working very hard. You need some rest and you must come along with us to Colombo”. Leo smiled, looked down and calmly responded, “Sir, thank you for the compliment, but let me say that this is not the time to rest, there’s plenty of work to be done”. He then went on to explain the underhand manner in which three lawyers, mentioning their names, who pretended to be great supporters of the government were acting. He went on to emphasize that he even had proof how they were hand in glove with insurgents and local criminals.

The IGP and Attygalle were conspicuously silent. After a few moments Leo spoke again. He said: ” If I come with you now, all these rascals will think that I was arrested and taken to Colombo. I will come to Police Headquarters on my own. Shall drive down this afternoon”.

Soon after the IGP and General Attygalle had left, at about 11 a.m. a high level team of investigators arrived from Colombo. This team consisted of Kenneth Seveniratne, Director of Public Prosecutions; Francis Pietersz, Director of Establishments and Cyril Herath, Director of Intelligence. Their mission was to carry out a general investigation into the happenings in Kurunegala. They were all my friends; my task was to give them whatever assistance they required. They were billeted with the Airforce and worked mainly from my office. They visited several places including the Kurunegala, Potuhera and Mawathagama police stations; and the Rest House which had been the meeting place and ‘watering hole’ of some of the lawyers during the height of the troubles. Many lawyers and several police officers were also questioned by them. They completed their assignment after about a week and left for Colombo.

Significantly they had not been able to find evidence of any wrongdoing by ASP Leo Perera. Before long I too was recalled to Colombo and asked to resume duties as the Director of Police Planning & Research. From this position too I was able to make useful contributions to the rehabilitation effort and particularly the fair and equitable distribution of the Terrorist Victim’s Fund.

Features

Evolution of Paediatric Medicine in Sri Lanka: Honouring Professor Herbert Aponso on his 100th Birthday.

Professor Herbert Allan Aponso, born on March 25, 1925, recently celebrated his 100th birthday at his serene home in Kandy. Surrounded by his cherished children, the occasion not only honoured his extraordinary life but also served as a tribute from his academic colleagues, recognising his outstanding contributions to the field of paediatrics in Sri Lanka. Professor Aponso is widely recognised for his exceptional ability to combine extensive field experience with academic teaching and groundbreaking research. He emphasised social causes of disease and maintained that a disease is not just a manifestation of biological factors in the human body, but an expression of social and environmental factors as well. He encouraged his students to consider social aspects, such as family factors and poverty, in order to explain diseases, particularly childhood diseases such as malnutrition.

Born in Lakshapathiya, Moratuwa, Aponso began his academic journey at Prince of Wales College, Moratuwa, excelling in the Senior School Certificate and London Matriculation Examinations. His medical aspirations led him to the University of Colombo in 1943 and subsequently to the Medical College, where he graduated MBBS with honours in 1949. Pursuing further specialisation, he trained in paediatrics at the prestigious Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, the largest and oldest children’s hospital in the UK, earning his DCH (London) in 1956 and MRCP (Edinburgh) in 1957.

Upon his return to Ceylon in 1958, Aponso earned his MD in Medicine and commenced a distinguished academic career. He joined the Faculty of Medicine in Colombo as a Senior Lecturer in 1963 and subsequently took on the role of Lecturer-in-Charge of Paediatrics at the University of Ceylon in Peradeniya in 1964. His career saw steady progression as he was promoted to Associate Professor in 1974 and ultimately attained the position of full Professor of Paediatrics in 1977.

Aponso was a Fellow of both the Royal College of Physicians (Edinburgh) and the Ceylon College of Physicians. He actively contributed to the Kandy Society of Medicine, where he served as President from 1974 to 1975. Beyond medicine, he played key roles in community organisations. Before relocating to Kandy, he was the president of the Moratuwa YMCA and a founding member of the Moratuwa Y’s Men Club. Later, he led the Kandy Y’s Men’s Club, which evolved into the Mahanuwara Y’s Men’s Club.

His contributions extended into promoting nutritional advancements, notably advocating for the consumption of soya. He pioneered the preparation of soya products in the kitchen of the Peradeniya Teaching Hospital and established a Soya Centre linked to the Kandy YMCA. Further showcasing his dedication to public health, he presided over the Sri Lanka Association for Voluntary Surgical Contraception and Family Health during two separate periods: 1977–1979 and 1986–1987. Additionally, he led the Sri Lanka Paediatric Association from 1976–1977.

Even after retiring from the University of Peradeniya in 1993, his impact endured. In recognition of his lifelong contributions, the university awarded him an honorary DSc in 2022. Through his tireless dedication, Professor Aponso profoundly influenced paediatric medicine in Sri Lanka, leaving an enduring legacy in both academic and medical spheres. Paediatrics as a specialised field of medicine in Sri Lanka has evolved over centuries, shaped by indigenous healing traditions, colonial medical advancements, and modern institutional developments. During colonial times under the Portuguese and Dutch, children continued to be treated through traditional medicine. The British colonial administration formalised Western medical education and established hospitals. In 1870, the Ceylon Medical College (now the Faculty of Medicine, University of Colombo) was founded, producing doctors trained in Western medicine. Paediatric care as a distinct discipline began to emerge in the early 20th century, having previously been part of general medicine. The introduction of vaccination programmes, particularly against smallpox, was a major public health advance introduced under the Vaccination Ordinance of 1886. It was during the1920s that Maternal and Child Health Clinics were setup in villages, laying the foundations for addressing child health issues in the country.

The early decades of the century saw the establishment of paediatric units in major hospitals, a critical step towards recognising and addressing the distinct medical needs of children. The establishment of paediatric units in major hospitals in Sri Lanka began in the mid-20th century, with significant developments occurring in the 1950s and 1960s. These units were set up to provide specialised care for children, addressing their unique medical needs. For example, the Lady Ridgeway Hospital for Children in Colombo became a national tertiary care centre, offering advanced paediatric services Hospitals such as the Colombo General Hospital (now the National Hospital of Sri Lanka) and played a pioneering role in creating specialised wards dedicated to paediatric care, laying the foundations for future advancements in the field.

A major turning point in the progress of paediatrics in Sri Lanka came with the appointment of Dr. C. C. de Silva as the first Professor of Paediatrics at the University of Ceylon (now the University of Colombo) in the 1950s. He was instrumental in formalising paediatric education and training, ensuring that future medical professionals were equipped with the knowledge and skills to provide specialised care for children. The introduction of dedicated paediatric courses in medical schools marked a shift from traditional general practice to a more specialised approach to child healthcare. The 1950s also saw the expansion of paediatric services beyond Colombo, with provincial hospitals establishing their own paediatric units, making specialised care accessible to a wider population.

The latter half of the 20th century witnessed remarkable progress in paediatric care, with the establishment of postgraduate training programmes aimed at producing highly qualified paediatricians. These programmes were designed to meet the increasing demand for specialised medical professionals who could address the complex healthcare needs of children. Alongside these educational advancements, there was a significant improvement in neonatal and maternal healthcare services, leading to better survival rates for newborns and reducing infant mortality. Innovations in paediatric research and healthcare policies further contributed to improvements in the overall well-being of children in Sri Lanka.

By the 1980s, paediatrics had firmly established itself as a distinct and essential medical discipline in Sri Lanka. The introduction of specialised paediatric subfields such as neonatology, cardiology, and nephrology allowed for more targeted treatment and improved health outcomes for children with complex medical conditions. The role of paediatricians expanded beyond hospital care, with increased involvement in public health initiatives such as immunisation programmes and nutritional interventions. The collaborative efforts of the government, medical institutions, and healthcare professionals ensured that paediatric care in Sri Lanka continued to progress in parallel with global medical advancements.

The development of paediatric specialization in Sri Lanka during the 20th century was a transformative journey that laid the groundwork for the country’s modern child healthcare system. From its humble beginnings in general hospital wards to the establishment of specialised training programmes and research initiatives, paediatrics evolved into a well-defined and essential medical discipline. This progress not only improved healthcare outcomes for children but also contributed to the overall strengthening of the medical field in Sri Lanka. Today, paediatrics continues to be a vital component of the healthcare system, building upon the foundations set during the 20th century to ensure a healthier future for the nation’s children. Professor Aponso was integral to the shaping of this process of development, in the 1950s and afterwards, fully engaged in every aspect. His involvement was not just academic, as he was an advisor to the government and other organisations, such as the World Health Organization, on matters about advancements in child health.

One of his most significant accomplishments was a six-year research project, generously funded by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA). This initiative was integral to addressing pressing health challenges within the Mahaweli Accelerated Development Programme in its initial phase. The project focused particularly on improving healthcare services in System ‘C’ of Girandurukotte, a region populated by settlers relocated from villages inundated due to the construction of large tanks and reservoirs. The programme was launched shortly after the settlers arrived, aiming to tackle the myriad health issues they encountered as newcomers to the dry zone settlements.

Under Aponso’s leadership, ‘mothers’ clubs’ were established in hamlets in each of the four settlement units chosen for intervention. These clubs became vital community spaces where families could engage in discussions about the health problems they faced. The challenges were numerous and varied, including skin diseases, issues with drinking water, snake bites, elephant attacks, and accidents sustained while working in newly cleared paddy lands. Malaria and flu posed an especially serious threat at the time, necessitating timely treatment.

The mothers’ clubs operated as dynamic forums where settlers could participate in question-and-answer sessions about their health concerns. These sessions often culminated in providing treatments for those afflicted. The efforts were supported by Dr. (Mrs.) Fernando, a dedicated health officer in ‘System C’ of Girandurukotte, who attended most of the meetings, ensuring professional medical assistance. Professor Aponso was also assisted by lecturers at the Department of Paediatrics and a health education officer, Mrs. Alagoda, whose skills in engaging with mothers played a pivotal role in the success of the discussions and outreach programmes.

During this period, the Centre for Intersectoral Community Health Studies (CICHS) emerged under the visionary leadership of Professor Aponso. As an interdisciplinary scholarly organisation dedicated to advancing health research in Sri Lanka, CICHS made remarkable strides in the field. Among its pioneering initiatives, the sexual-risk prevention programme stood out as a milestone. This programme prioritised fostering individual competencies while shaping cultural norms that encourage healthy sexual decision-making, reflecting the organisation’s commitment to impactful research and community well-being.

As the project manager of the WHO/CIDA project, I had the privilege of working closely with Professor Aponso. I travelled frequently from my office at the Department of Paediatrics at Peradeniya to the villages, coordinating the programme’s activities. We collected household data on a sample within selected settlement units, such as Teldeniyaya, Hombariyawa, Millaththewa and Rambewa. To make a comparison, we also collected data from Mawanella rural villages, which was considered the control area. This information was then meticulously analysed using an IBM computer, a remarkable technological feat at a time when computers were a rarity.

Our research team, comprising approximately ten recent sociology graduates, including KMHB Kulasekera, RM Karunasekara and Nandani de Silva, worked tirelessly to collect, compile and interpret the data. The findings were shared at various conferences in the form of scholarly articles, providing valuable contributions to both national and global conversations on the public health challenges faced by communities in transition.

Professor Aponso’s work not only made a profound impact on the lives of those settlers but also left an indelible mark on the field of social paediatrics, demonstrating the transformative power of community-based health initiatives supported by collaborative research.

Aponso’s contributions to child healthcare, particularly in the areas of neonatology, nutrition, and medical education are important. As a student of Dr. C. C. de Silva, he was deeply influenced by his mentor’s pioneering work in paediatrics and carried forward his legacy by further strengthening child healthcare services in Sri Lanka. Dr. L.O. Abeyratne was the first Professor of Paediatrics at Peradeniya, and, upon his retirement, Professor Aponso succeeded him, continuing to advance paediatric education and healthcare in Sri Lanka. Aponso was particularly known for his work in neonatal care and the prevention of childhood malnutrition. He played a key role in introducing and promoting best practice in newborn care, helping to reduce infant mortality rates in Sri Lanka. His advocacy for improved maternal and child health policies contributed to the expansion of paediatric services beyond Colombo, ensuring that specialized care was accessible to children in rural areas as well.

Beyond clinical practice, Professor Aponso was a dedicated medical educator. He trained and mentored numerous paediatricians, helping to shape the next generation of child healthcare professionals in Sri Lanka. His work in medical research and teaching influenced advancements in paediatric care and was

instrumental in establishing higher standards in paediatric training programmes. In 2011, in commemoration of his work, Dr. Ananda Jayasinghe edited a collection of essays titled ‘In honour of Herbert Allan Aponso, emeritus professor of paediatrics, University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka.’

Professor Aponso is a remarkable individual whose humility is as profound as his ability to listen with intention and honour to the perspectives of those around him. A celebrated expert in his field, he was elected President of the Sri Lanka Paediatric Association in 1976 and ascended to the role of full Professor of Paediatrics in 1977. His dedication extended far beyond academia—he served as President of the Young Men’s Christian Association in Kandy during three pivotal periods: 1966–1968, 1973–1975, and 1984–1988.

In 1952, he embarked on a lifelong partnership with Jayanthi Vimala Dias, now deceased, building not just a family but a legacy of intellect and social impact. Together, they raised three children—Ajith, Heshan, and Charmalie—who each distinguished themselves in society. Their home became a vibrant epicentre of stimulating dialogue and collaborative ideas, welcoming friends to partake in lively, thought-provoking discussions.

For me, the memory of Professor Aponso is forever intertwined with the dynamic days of the Mahaweli research project and CICHS initiatives, where his presence enriched every endeavour. As he continues his retirement journey, I wish him abundant health and days brimming with vitality, joy, and a renewed sense of purpose.

by M. W. Amarasiri de Silva

(Emeritus Professor of Sociology, University of Peradeniya Sri Lanka and Lecturer at the University of California, Santa Cruz, USA).

Features

Indian colonialism in Sri Lanka

Following independence from Britain, both India and Sri Lanka emerged as leaders of the Non-Aligned Movement, which sought to advance developing nations’ interests during the Cold War. Indeed, the term “non-alignment” was itself coined by Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru during his 1954 speech in Colombo. The five principles of the Non-Aligned Movement are: “mutual respect for each other’s territorial integrity and sovereignty; mutual non-aggression; mutual non-interference in domestic affairs; equality and mutual benefit; and peaceful co-existence.”

Later, Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi played a key role in supporting Sri Lankan Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike’s 1971 proposal to declare the Indian Ocean a Zone of Peace at the United Nations.

Such progressive ideals are in stark contrast to the current neocolonial negotiations between the two countries.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s forthcoming visit to Sri Lanka on April 4, 2025, is presented as representing a mutually beneficial partnership that will bring economic development to debt-burdened Sri Lanka. However, the details of the strategic agreements to be signed during Modi’s visit remain undisclosed to the public. This opacity cannot be a good sign and should not be accepted uncritically by the media or the people of either nation.

The Indo-Lanka Agreement of July 29, 1987, was also crafted without consultation with the Sri Lankan people or its parliament. It was signed during a 48-hour curfew when former Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi arrived in Sri Lanka. This agreement led to the imposition of the 13th Amendment to the Sri Lankan Constitution and established the Provincial Council system. The political framework it created continues to challenge Sri Lanka’s territorial integrity and sovereignty. Rather than bringing peace, India’s 1987 intervention resulted in one of the most violent and chaotic periods in the island’s recent history.

Will these agreements being finalised with Prime Minister Modi also lead to a period of pillage and plunder of the island’s resources and worsening conditions for its people, rather than delivering the promised economic benefits? It is crucial that any bilateral agreements include enforceable measures to stop Indian bottom trawlers from illegally fishing in Sri Lankan territorial waters. This decades-long practice has caused severe damage to Sri Lanka’s marine resources and inflicted significant economic losses on its fishing communities.

Facing an increasing Chinese presence in Sri Lanka and the Indian Ocean, India has sought to strengthen its political, economic, strategic and cultural influence over Sri Lanka through various overt and covert means. During Sri Lanka’s 2022 economic crisis, for example, India provided $4 billion in financial assistance through currency swaps, credit lines, and loan deferrals that enabled Sri Lanka to import essential goods from India. While this aid has helped Sri Lanka, it has also served India’s interests by countering China’s influence and protecting Indian business in Sri Lanka.

Prime Minister Modi’s upcoming visit represents the culmination of years of Indian initiatives in Sri Lanka spanning maritime security, aviation, energy, power generation, trade, finance, and cultural exchanges. For example, India’s Unified Payment Interface (UPI) for digital payments was introduced in Sri Lanka in February 2024, and in October 2023 India provided funds to develop a digital national identity card for Sri Lanka raising concerns about India’s access to Sri Lanka’s national biometric identification data. Indian investors have been given preferential access in the privatisation of Sri Lanka’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in key sectors like telecommunications, financial services, and energy. Adani Group’s West Terminal project in Colombo Port is explicitly designed to counter China’s control over Sri Lanka’s port infrastructure, including the Colombo International Container Terminal, Hambantota Port, and Port City Colombo.

India and Sri Lanka have recently agreed to resume negotiations on the Economic and Technology Cooperation Agreement (ETCA), which focuses primarily on the service sector and aims to create a unified labour market. However, Sri Lankan professional associations have raised concerns that ETCA could give unemployed and lower-paid Indian workers a competitive advantage over their Sri Lankan counterparts. These concerns must be properly addressed before any agreement is finalised.

On December 16, 2024, India and Sri Lanka signed several Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) in New Delhi to enhance cooperation in defense, energy, and infrastructure development. These include plans for electricity grid interconnection and a multi-product petroleum pipeline between the two countries. Building on these agreements, construction of the Sampur power plant in Trincomalee is expected to begin during Prime Minister Modi’s April visit.

The Sampur power plant project, combined with India’s takeover of the Trincomalee Oil Tank Farm, represents a significant step toward integrating Sri Lanka into India’s national energy grid. This development effectively brings Trincomalee’s strategic natural harbour – often called the “crown jewel” of Sri Lanka’s assets – under Indian control, transforming it into a regional energy hub. In 1987, during India’s military intervention in Sri Lanka, New Delhi pressured Colombo into signing a secret agreement stipulating that the British-era Trincomalee oil tank farm would be jointly developed with India and could not be used by any other country.

While India promotes its energy interconnection projects as enhancing regional energy security, recent experiences in Nepal demonstrate how electricity grid integration with India has made Nepal dependent on and subordinate to India for its basic energy needs. Similarly, Bangladesh’s electricity agreement with the Adani Group has created an imbalanced situation favouring Adani over Bangladeshi power consumers. What collective actions could Sri Lanka and other small nations take to avoid such unequal “energy colonialism” and protect their national security and sovereignty?

India’s emergence as a superpower and its expansionist policies are gradually transforming neighbouring South Asian and Indian Ocean states into economically and politically subordinate entities. Both Sri Lanka and the Maldives have adopted “India First” foreign policies in recent years, with the Maldives abandoning its “India Out” campaign in October 2024 in exchange for Indian economic assistance.

India’s “Neighbourhood First Policy” has led to deep involvement in the internal affairs of neighbouring countries including Sri Lanka. This involvement often takes the form of manipulating political parties, exploiting ethnic and religious divisions, and engineering political instability and regime changes – tactics reminiscent of colonial practices. It is well documented that India provided training to the LTTE and other terrorist groups opposing the Sri Lankan government during the civil war.

Contemporary Indian expansionism must be viewed within the broader context of the New Cold War and intensifying geopolitical competition between the United States and China. Given its strategic location along the vital east-west shipping routes in the Indian Ocean, Sri Lanka has become a pawn in this great power rivalry. In addition to granting China extensive control over key infrastructure, Sri Lanka has signed the Acquisition and Cross-Servicing Agreement (ACSA) and Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) with the United States, effectively allowing the use of Sri Lanka as a U.S. military logistics hub. It was reported that during a visit to Sri Lanka in February 2023, Victoria Nuland, former Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs of the United States strongly suggested the establishment of a joint US-Indian military base in Trincomalee to counter Chinese activities in the region.

As a member of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) – a strategic alliance against Chinese expansion that includes the United States, Australia and Japan – India participates in extensive QUAD military exercises like the Malabar exercises in the Indian Ocean. However, India’s role in QUAD appears inconsistent with its position as a founding member of BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa), which was established to promote the interests of emerging economies and a multipolar world order. Unfortunately, BRICS appears to be replicating the same patterns of domination and subordination in its relations with smaller nations like Sri Lanka that characterise traditional imperial powers.

India presents itself as the guardian of Buddhism, particularly in its relations with Sri Lanka, to foster a sense of shared cultural heritage. However, it was Sri Lanka – not India – that preserved the Buddha’s teachings as they declined and eventually disappeared from India. Sri Lanka maintained the Buddhist tradition despite seventeen major invasions from India aimed at destroying the island’s Buddhist civilization.

Even today, despite its extensive influence, India has not taken meaningful steps to protect Buddhist temples and archaeological sites in Sri Lanka’s north and east from attacks by Tamil separatist groups. Instead, India appears focused on advancing the concept of Akhand Bharat (Undivided India) and Hindu Rashtra (Hindu Nation), which seeks to incorporate neighboring countries like Sri Lanka into a “Greater India.” The promotion of the bogus Ramayana Trail in Sri Lanka and the accompanying Hinduization pose a serious threat to preserving Sri Lanka’s distinct Buddhist identity and heritage.

Indian neocolonialism in Sri Lanka reflects a global phenomenon where powerful nations and their local collaborators – including political, economic, academic, media and NGO elites – prioritize short-term profits and self-interest over national and collective welfare, leading to environmental destruction and cultural erosion. Breaking free from this exploitative world order requires fundamentally reimagining global economic and social systems to uphold harmony and equality.

In this global transformation, India has a significant role to play. As a nation that endured centuries of Western imperial domination, India’s historical mission should be to continue to lead the struggle for decolonization and non-alignment, rather than serving as a junior partner in superpower rivalries. Under Mahatma Gandhi’s leadership, India championed the worldwide movement for decolonization and independence in the modern era.

Upholding the principles of the Non-Aligned Movement could forge a partnership benefiting both nations while preserving Sri Lanka’s independence and Buddhist identity. Otherwise, the New Cold War will continue to trample local sovereignty, where foreign powers vie to exploit the island’s resources, subjugate local communities and accelerate environmental and cultural destruction.

by Dr. Asoka Bandarage

Features

Batalanda Skeletons, Victims’ Sorrows and NPP’s Tasks

Few foresaw skeletons of Batalanda come crashing down in a London television interview. There have been plenty of speculations about the intended purposes and commentaries on the unintended outcomes of Ranil Wickremesinghe’s Al Jazeera interview. The more prurient takes on the interview have been about the public dressing down of the former president by the pugnacious interviewer Mehdi Hasan. Only one person seems convinced that Mr. Wickremesinghe had the better of the exchanges. That person is Ranil Wickremesinghe himself. That is also because he listens only to himself, and he keeps himself surrounded by sidekicks who only listen and serve. But there is more to the outcome of the interview than the ignominy that befell Ranil Wickremesinghe.

Political commentaries have alluded to hidden hands and agendas apparently looking to reset the allegations of war crimes and human rights violations so as to engage the new NPP government in ways that would differentiate it from its predecessors and facilitate a more positive and conclusive government response than there has been so far. Between the ‘end of the war’ in 2009, and the election of President Anura Kumara Dissanayake and the NPP government in 2024, there have been four presidents – Mahinda Rajapaksa, Maithripala Sirisena, Gotabaya Rajapaksa and Ranil Wickremesinghe – and as many governments. Of the four, Ranil Wickremesinghe is the least associated with the final stages of the war and its ending. In fact, he was most associated with a failed, even flawed peace process that ultimately ensured the resumption of the war with vengeance on both sides. RW was also the most receptive to war crimes investigations even proffering that external oversight would not be a violation of Sri Lanka’s Constitution.

One school of thought about the Al Jazeera interview is that those who arranged it were hoping for Ranil Wickremesinghe to reboot the now stalling war crimes project and bring pressure on the NPP government to show renewed commitment to it. From the looks of it, the arrangers gave no thought to Ranil Wickremesinghe’s twin vulnerabilities – on the old Batalanda skeletons and the more recent Easter Sunday bombings. If Easter Sunday was a case of criminal negligence, Batalanda is the site of criminal culpability. In the end, rather than rebooting the Geneva project, the interview resurrected the Batalanda crimes and its memories.

The aftermath commentaries have ranged between warning the NPP government that revisiting Batalanda might implicate the government for the JVP’s acts of violence at that time, on the one hand, and the futility of trying to hold anyone from the then government accountable for the torture atrocities that went on in Batalanda, including Ranil Wickremesinghe. What is missing and overlooked in all this is the cry of the victims of Batalanda and their surviving families who have been carrying the burden of their memories for 37 years, and carrying as well, for the last 25 years, the unfulfilled promises of the Commission that inquired into and reported on Batalanda.

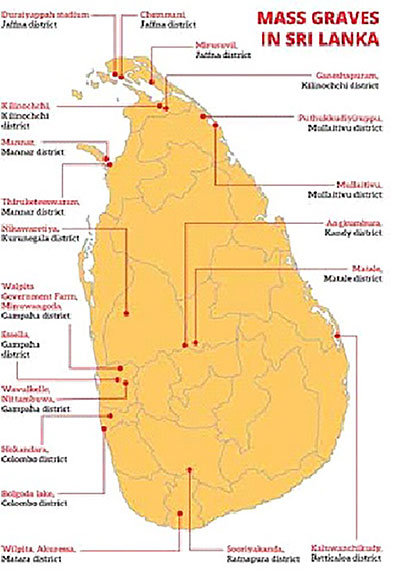

The families impacted by Batalanda gave a moving illustration of the agony they have been going through for all these years in a recent media briefing, in Colombo, organized by the indefatigable human rights activist Brito Fernando. I am going by the extensive feature coverage of the media event and the background to Batalanda written by Kamanthi Wickremesinghe in the Daily Mirror (March 20, 2025). I am also borrowing her graphics for illustration – a photograph of the media briefing and a map of Sri Lanka showing the scattered sites of mass graves – 20 in all.

“We express gratitude to this government for providing the environment to discuss and debate about the contents of this report,” said Brito Fernando, speaking for the families. After addressing Ranil Wickremesinghe’s obfuscations about his involvement, and decrying Chandrika Kumaratunga’s failure to act on the recommendations of the report of the Batalanda Commission of Inquiry she created, Mr. Fernando appealed to the present NPP government to “provide a secure environment where these victims could come out and speak about their experiences,” Nothing more, nothing less, and that is all there is to it.

Whatever anyone else might say, the victims of Batalanda and their survivors have vindicated the NPP government’s decision to formally table the Batalanda Commission Report in parliament. As for their continuing expectations, Brito Fernando went on say, “We have some hopes regarding this government, but they should walk the talk.” Mr. Fernando suggested that the government should co-ordinate with the UNHRC’s Sri Lanka Accountability Project that has become a valuable resource for preserving evidence and documentation involving human rights crimes and violations over many decades. In addition, Mr. Fernando pointed out that the grieving families have not been involved in the ongoing excavations of mass graves, and they are anxious to receive the remains of their dear ones after their identity is confirmed through DNA analyses. Nor has there been any sign of legal action being taken against any of the suspects connected to the mass graves.

Whatever anyone else might say, the victims of Batalanda and their survivors have vindicated the NPP government’s decision to formally table the Batalanda Commission Report in parliament. As for their continuing expectations, Brito Fernando went on say, “We have some hopes regarding this government, but they should walk the talk.” Mr. Fernando suggested that the government should co-ordinate with the UNHRC’s Sri Lanka Accountability Project that has become a valuable resource for preserving evidence and documentation involving human rights crimes and violations over many decades. In addition, Mr. Fernando pointed out that the grieving families have not been involved in the ongoing excavations of mass graves, and they are anxious to receive the remains of their dear ones after their identity is confirmed through DNA analyses. Nor has there been any sign of legal action being taken against any of the suspects connected to the mass graves.

The map included here shows twenty identified mass graves spread among six of the country’s nine provinces. There could be more of them. They are a constant reminder of the ravages that the country suffered through over five decades. They are also a permanent source of pain to those whose missing family members became involuntary tenants in one or another mass grave. The families and communities around these mass graves deserve the same opportunity that the impacted families of Batalanda have been given by the current exposure of the Batalanda Commission Report.

The primary purpose of dealing with past atrocities and the mass graves that hold their victims is to give redress to survivors of victims, tend to their long lasting scars and reengage them as free and full members of the community. Excavation and Recovery, DNA Analysis and Community Engagement have become the three pillars of the recuperation process. Sri Lanka is among nearly a hundred countries that are haunted by mass graves. Many of them have far greater numbers of mass graves assembled over even longer periods. Suffering and memories are not quantitative; but unquantifiable and ineluctable emotions. The UN counts three buried victims as a mass grave. Even a single mass grave is one too many.

To do nothing about them is a moral and social copout at every level of society and in the organization of its state. Normalising the presence of mass graves is never an option for those who live around them and have their family members buried in them. Not for them who have built up over centuries, emotional systems of rituals for parting with their beloved ones. And it should not be so for governments that would otherwise go digging anywhere and everywhere in pseudo-archaeological pursuits.

Mass graves are created because of government actions and actions against governments. But governments come and go, and people in governments and political organizations change from time to time. There is a new government in town with a new generation of members in the Sri Lankan parliament, and it is time that this government revisited the country’s past and started providing even some redress to those who have suffered the most. The families of the Batalanda victims have vindicated the NPP government’s action to officially publicise the Batalanda Commission Report. The government must move on in that direction ignoring the carping of critics who selectively remember only the old JVP’s past.

There is more to what the government can do beyond mass graves. The Batalanda Commission Report is one of reportedly 36 such reports and each Commission has provided its fact findings and recommendations. Hardly any of them have been acted upon – not by the governments that appointed them and not by the governments that came after and created their own commissions. The JVP government must seriously consider creating a one last Commission, a Summary Commission, so to speak, to pull together all the findings and recommendations of previous commissions and identify steps and measures that could be integrated into ongoing initiatives and programs of the government.

The cynical alternative is to throw up one’s hands and do nothing, similar to cynically leaving the mass graves alone and doing nothing about them. The more sinister alternative was what Gotabaya Rajapaksa attempted when he appointed a new Commission of Inquiry to “assess the findings and recommendations” of previous commissions. That attempt was roundly condemned as a witch hunt against political opponents set up under the 1978 Commissions of Inquiry Act that was specifically enacted to enable the targeting political opponents under the guise of an inquiry. Repealing that act should be another consideration for the NPP government.

I am just floating the idea of a Summary Commission as a potential framework to bring positive closure to all the war crimes, emblematic crimes and human rights violations that have been plaguing Sri Lanka for the entire first quarter of this century. It is a political idea befitting the promises of a still new government, and one that would also be a positive fit for the government’s much touted Clean Sri Lanka initiative. For sure, it would be moral cleansing along with physical cleansing. A Summary Commission could also provide a productive forum for addressing the pathetic dysfunctions of the whole law and order system. The NPP government inherited a wholly broken down law and order system from its predecessors, but its critics suddenly see a national security crisis and it is all this government’s fault.

More substantively, a Summary Commission could tap into the resources of the UNHRC in collegial and collaborative ways without the hectoring and adversarial baggage of the past. These must be trying times for the UNHRC, as indeed for all UN agencies, given the full flight of Trumpism in America and its global spill over. Sri Lanka is one of a handful of countries where UNHRC professionals might find some headway for their mission. And the NPP government could be a far more reliable partner than any of its predecessors.

by Rajan Philips

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoSri Lanka’s eternal search for the elusive all-rounder

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoCelebrating 25 Years of Excellence: The Silver Jubilee of SLIIT – PART I

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoCEB calls for proposals to develop two 50MW wind farm facilities in Mullikulam

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoAIA Higher Education Scholarships Programme celebrating 30-year journey

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoGnanasara Thera urged to reveal masterminds behind Easter Sunday terror attacks

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoNotes from AKD’s Textbook

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoComBank crowned Global Finance Best SME Bank in Sri Lanka for 3rd successive year

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoSanctions by The Unpunished