Features

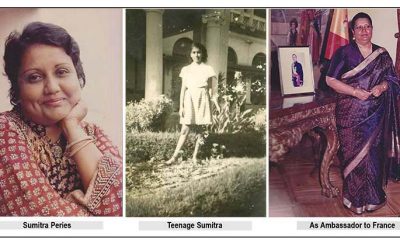

Sumithra ( 1935 – 2023 )

By Uditha Devapriya

My Lunches with Orson is the title of a collection of interviews that Henry Jaglom, a US avant-garde filmmaker, did with Orson Welles, over a period of two years (1983-1985). It is at once insightful, refreshing, provocative, and compelling, and it shows Welles at his best. At the time, Jaglom was around 10 years into his own career; he had tried his best to stage a comeback for Welles, and failed. The book reveals Jaglom’s admiration for Welles, and more than anything, the potential Welles possessed, which was in effect denied to him.

Re-reading Jaglom’s book, the other day, I suddenly remembered Sumitra Peries. Peries passed away last Thursday. That morning, I received a call from a friend of hers, telling me that she had been admitted to hospita, owing to a stomach ailment. An hour later, they announced her death. It was just too sudden, shocking, and saddening.

I sat down, pondering the many conversations we had shared at her place, processing the fact that there would be no sequel to them. I thought back on her career and her legacy. Put simply, it seemed as hard for me to see the full-stop in the mirror, as it would have been for Kusum, at the end of Gehenu Lamayi (1978), to see the question mark in hers.

“The end of an era,” a mentor of mine, a distant relative of hers, messaged from Toronto. A convenient cliché, but in this case, a most suitable summing up.

For Sumitra Peries was not just a symbol of some golden and bygone era. She was its last emissary, its last survivor, its last face. Her husband epitomised that period no less: his passing away, five years ago, signified the beginning of a transition. With Sumitra’s passing, that transition is now complete. The question is, what do we make of it?

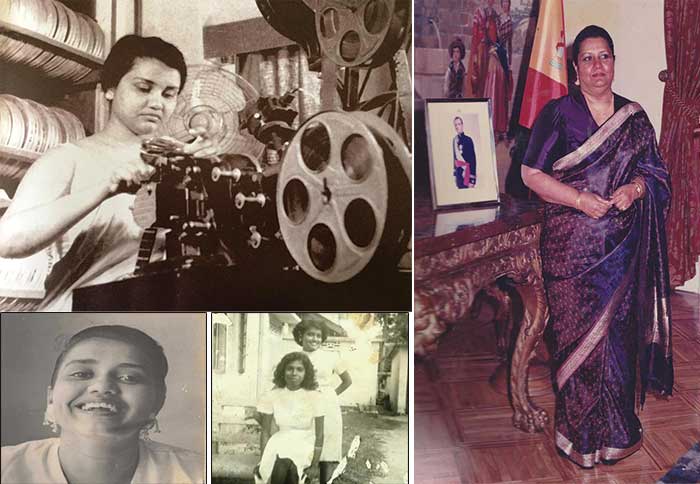

Sumitra was not just a director, an editor, or an assistant, though she wore these titles in her life. She was also an indefatigable connoisseur and a gadfly, who happened to dislike the process of writing and speaking. She hardly wrote to the press and was reluctant to talk in front of a crowd. “I don’t want to,” she once told me. “I simply can’t get myself to do it,” she quipped on another occasion. As such, we lack the anthologies, the essays, the reviews, the reflections, which her husband had and got published in his lifetime.

In other words, we lack material for a memoir or a biography. This should force us to engage with her legacy, as one of our last great icons: those who hailed from the colonial period and saw through some of this country’s most pivotal social transformations.

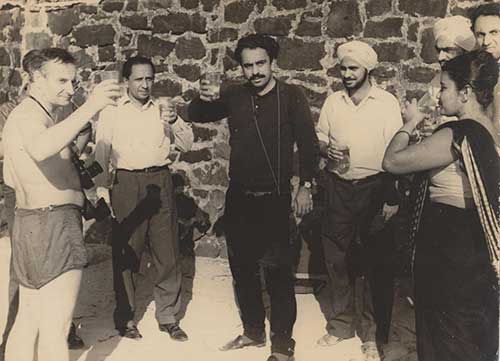

Her life and career have been charted many times before, by many writers. By themselves, they constitute the stuff of films: hailing from a rural upper middle-class; born to a socialist and radical political heritage from her father’s and uncles’ side; displaying a rebellious streak as a teenager and a young adult; travelling solo to meet her brother in Malta, before even turning 21; and living on her own in Lausanne and Paris, before suddenly whisking herself off to Brixton, in London. In all this, she remained a woman ahead of her time, daring enough to explore her frontiers, but also pragmatic enough to know how far she could reach out, and when she had to retreat. Eventually, she returned to her place of birth and sought work as an editor, on her husband’s films, soon carving her own path.

In all this, Sumitra tends to be framed as Lester James Peries’s significant other: which she was, to a certain extent. Her work as editor on Lester’s films – on the best he ever made, from Gamperaliya (1963) to Golu Hadawatha (1969), as well as his masterpiece, Nidhanaya (1970) – helped her grasp an art form she had studied in England.

Yet such a reading of her life reduces her to a mere adjunct, an appendage whose only function was to sustain her husband’s work. To understand Sumitra’s contribution to the cinema, we thus need to go beyond this framing of her, and, instead, critically reflect on her relationship with Lester and the world he opened her up to. To do so, we need to invert the conventional reading of her: we need to chart the world she opened him up to.

Sumitra was linked through her husband to some of the most exciting strides in the arts and culture that were making themselves felt in post-independence Sri Lanka, and not only in film. Lester James Peries’s brother, Ivan (1921-1988), had been one of the leading figures of the ’43 Group, which challenged establishment circles and sought a modernist revolution in the arts. Born to largely middle-class and Westernised milieux, the ’43 Group laid the seeds of the cultural revolution that was to flow years later, after 1956. Not everyone in the Group shared the political convictions and the nationalist ideals that made 1956 possible. But even if they didn’t share them, they still considered them inevitable.

Despite the enthusiasm of its founders, however, the ’43 Group was not without its flaws and limitations. “The verve and the enthusiasm of the forties,” Ian Goonetileke observed many decades later, “petered out, perhaps because they were insufficiently grounded in the bedrock of the cultural patterns of Sri Lanka.” Goonetileke noted the fatal paradox which underlay, and undergirded, Sri Lanka’s most promising avant-garde movement: its lack of familiarity with the very culture it sought inspiration from. “I wasn’t rooted in my culture,” Lester Peries once admitted to me. In part, this was due to their Westernised and Christian upbringing: “We were actively forbidden to look into or be interested in other cultures.” To be intrigued by the latter was to invite punishment: “Going to a Buddhist funeral was out of the question. You had to pay penance if you did such a thing.”

These limitations crippled most of the other members of the ’43 Group, and many of those who followed it as well. To be sure, Lester’s maiden work, Rekava (1956), significantly broke with all the conventions and formulae of the Sinhala film. However, we need to place such achievements in their context. In her biography of Sumitra Peries, Vilasnee Tampoe-Hautin puts it that “all Sinhala-speaking films were born in South India.” Born, bred, and buttered in the Madras studio, the Sinhala cinema, therefore, remained an enigmatic paradox. With his Westernised ethos, Lester may have found this state of affairs too infuriating to tolerate: as he was fond of saying, the Indian film was “neither Indian nor film.”

However, while challenging, what I like to term, the South Indian orientation of Sri Lankan films, Rekava was, in later years, castigated by those who felt that its view of peasant life, in a Sinhala village, was too artificial and too contrived. While Lester, and his cast and crew, had departed from the patterns of the conventional Sinhala film, many, if not most, of them were not grounded properly in the culture they sought to depict and exhibit in it. They wanted to be true to life, but their very backgrounds constrained them.

In other words, while they had ruptured the South Indian domination of Sri Lankan cinema, they were unable to bypass their personal limitations. This was as true of Rekava as it was of the’43 Group and of the cultural elites that had moulded it.

Much of this intelligentsia thus failed to make the proverbial leap. Many, like Lester’s own brother, emigrated to fairer climes; others, like Justin Deraniyagala, retreated to a world of their own. A few managed to question their intellectual inheritance and go beyond: among them, the most prominent would be George Keyt (1901-1993). In Keyt’s case, however, his childhood interest in Buddhism, and his marriage to a Sinhalese, and later an Indian Muslim, pushed him away from his Anglicised, middle-class background. I think that was the key to Keyt’s evolution: in effect, his marriage to those far more rooted in their society helped him defy his limitations. That proved to be no less useful to Lester. This is where we should place Sumitra and her contribution, to the cinema and to her husband’s work.

Hailing from a staunchly traditional, yet politically radical family, Sumitra represented, at every level, the antithesis of Lester’s upbringing. Speaking at a function, nearly 10 years ago, Sunil Ariyaratne rather flippantly outlined the differences: Catholic/Buddhist, city/village, conservative/socialist, UNP/LSSP. These contradictions did not split the two of them apart; rather, they brought them together and welded the one to the other.

Sumitra’s enduring contribution to her husband’s career, which critics, who perceive her as a mere appendage to his work fail, to note, was hence to turn him away from his inheritance and bring him closer to a culture he so desperately wished to depict. In doing so, I think she helped Lester transcend the limitations that the other members of the ’43 Group, to which he belonged by proxy, could not. Through that, the two of them managed to bring about the revolution of the arts that 1956 had so tantalisingly heralded.

There is certainly no doubt that Sumitra Peries will be missed. She did much more than what critics, and journalists, concede, and her contributions are vaster than we give her credit for. In the absence of any written, or even oral evidence, from her side, however, it behoves us to explore and assess what she did and put it to paper. I believe this is the task of the intrepid historian, critic, journalist, and biographer. Such an endeavour is urgently needed now, at a time when, quoting that Gramscian quip, the old world is dying and the new struggles to be born. Sumitra’s death symbolises a passing and a transition. One only hopes that we do not forget her legacy, and, more importantly, what we should do about it.

(The writer is an international relations analyst, researcher, and columnist who can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com)

Features

Sustaining good governance requires good systems

A prominent feature of the first year of the NPP government is that it has not engaged in the institutional reforms which was expected of it. This observation comes in the context of the extraordinary mandate with which the government was elected and the high expectations that accompanied its rise to power. When in opposition and in its election manifesto, the JVP and NPP took a prominent role in advocating good governance systems for the country. They insisted on constitutional reform that included the abolition of the executive presidency and the concentration of power it epitomises, the strengthening of independent institutions that overlook key state institutions such as the judiciary, public service and police, and the reform or repeal of repressive laws such as the PTA and the Online Safety Act.

The transformation of a political party that averaged between three to five percent of the popular vote into one that currently forms the government with a two thirds majority in parliament is a testament to the faith that the general population placed in the JVP/ NPP combine. This faith was the outcome of more than three decades of disciplined conduct in the aftermath of the bitter experience of the 1988 to 1990 period of JVP insurrection. The manner in which the handful of JVP parliamentarians engaged in debate with well researched critiques of government policy and actions, and their service in times of disaster such as the tsunami of 2004 won them the trust of the people. This faith was bolstered by the Aragalaya movement which galvanized the citizens against the ruling elites of the past.

In this context, the long delay to repeal the Prevention of Terrorism Act which has earned notoriety for its abuse especially against ethnic and religious minorities, has been a disappointment to those who value human rights. So has been the delay in appointing an Auditor General, so important in ensuring accountability for the money expended by the state. The PTA has a long history of being used without restraint against those deemed to be anti-state which, ironically enough, included the JVP in the period 1988 to 1990. The draft Protection of the State from Terrorism Act (PSTA), published in December 2025, is the latest attempt to repeal and replace the PTA. Unfortunately, the PSTA largely replicates the structure, logic and dangers of previous failed counter terrorism bills, including the Counter Terrorism Act of 2018 and the Anti Terrorism Act proposed in 2023.

Misguided Assumption

Despite its stated commitment to rule of law and fundamental rights, the draft PTSA reproduces many of the core defects of the PTA. In a preliminary statement, the Centre for Policy Alternatives has observed among other things that “if there is a Detention Order made against the person, then in combination, the period of remand and detention can extend up to two years. This means that a person can languish in detention for up to two years without being charged with a crime. Such a long period again raises questions of the power of the State to target individuals, exacerbated by Sri Lanka’s history of long periods of remand and detention, which has contributed to abuse and violence.” Human Rights lawyer Ermiza Tegal has warned against the broad definition of terrorism under the proposed law: “The definition empowers state officials to term acts of dissent and civil disobedience as ‘terrorism’ and will lawfully permit disproportionate and excessive responses.” The legitimate and peaceful protests against abuse of power by the authorities cannot be classified as acts of terror.

The willingness to retain such powers reflects the surmise that the government feels that keeping in place the structures that come from the past is to their benefit, as they can utilise those powers in a crisis. Due to the strict discipline that exists within the JVP/NPP at this time there may be an assumption that those the party appoints will not abuse their trust. However, the country’s experience with draconian laws designed for exceptional circumstances demonstrates that they tend to become tools of routine governance. On the plus side, the government has given two months for public comment which will become meaningful if the inputs from civil society actors are taken into consideration.

Worldwide experience has repeatedly demonstrated that integrity at the level of individual leaders, while necessary, is not sufficient to guarantee good governance over time. This is where the absence of institutional reform becomes significant. The aftermath of Cyclone Ditwah in particular has necessitated massive procurements of emergency relief which have to be disbursed at maximum speed. There are also significant amounts of foreign aid flowing into the country to help it deal with the relief and recovery phase. There are protocols in place that need to be followed and monitored so that a fiasco like the disappearance of tsunami aid in 2004 does not recur. To the government’s credit there are no such allegations at the present time. But precautions need to be in place, and those precautions depend less on trust in individuals than on the strength and independence of oversight institutions.

Inappropriate Appointments

It is in this context that the government’s efforts to appoint its own preferred nominees to the Auditor General’s Department has also come as a disappointment to civil society groups. The unsuitability of the latest presidential nominee has given rise to the surmise that this nomination was a time buying exercise to make an acting appointment. For the fourth time, the Constitutional Council refused to accept the president’s nominee. The term of the three independent civil society members of the Constitutional Council ends in January which would give the government the opportunity to appoint three new members of its choice and get its way in the future.

The failure to appoint a permanent Auditor General has created an institutional vacuum at a critical moment. The Auditor General acts as a watchdog, ensuring effective service delivery promoting integrity in public administration and providing an independent review of the performance and accountability. Transparency International has observed “The sequence of events following the retirement of the previous Auditor General points to a broader political inertia and a governance failure. Despite the clear constitutional importance of the role, the appointment process has remained protracted and opaque, raising serious questions about political will and commitment to accountability.”

It would appear that the government leadership takes the position they have been given the mandate to govern the country which requires implementation by those they have confidence in. This may explain their approach to the appointment (or non-appointment) at this time of the Auditor General. Yet this approach carries risks. Institutions are designed to function beyond the lifespan of any one government and to protect the public interest even when those in power are tempted to act otherwise. The challenge and opportunity for the NPP government is to safeguard independent institutions and enact just laws, so that the promise of system change endures beyond personalities and political cycles.

by Jehan Perera

Features

General education reforms: What about language and ethnicity?

A new batch arrived at our Faculty again. Students representing almost all districts of the country remind me once again of the wonderful opportunity we have for promoting social and ethnic cohesion at our universities. Sadly, however, many students do not interact with each other during the first few semesters, not only because they do not speak each other’s language(s), but also because of the fear and distrust that still prevails among communities in our society.

A new batch arrived at our Faculty again. Students representing almost all districts of the country remind me once again of the wonderful opportunity we have for promoting social and ethnic cohesion at our universities. Sadly, however, many students do not interact with each other during the first few semesters, not only because they do not speak each other’s language(s), but also because of the fear and distrust that still prevails among communities in our society.

General education reform presents an opportunity to explore ways to promote social and ethnic cohesion. A school curriculum could foster shared values, empathy, and critical thinking, through social studies and civics education, implement inclusive language policies, and raise critical awareness about our collective histories. Yet, the government’s new policy document, Transforming General Education in Sri Lanka 2025, leaves us little to look forward to in this regard.

The policy document points to several “salient” features within it, including: 1) a school credit system to quantify learning; 2) module-based formative and summative assessments to replace end-of-term tests; 3) skills assessment in Grade 9 consisting of a ‘literacy and numeracy test’ and a ‘career interest test’; 4) a comprehensive GPA-based reporting system spanning the various phases of education; 5) blended learning that combines online with classroom teaching; 6) learning units to guide students to select their preferred career pathways; 7) technology modules; 8) innovation labs; and 9) Early Childhood Education (ECE). Notably, social and ethnic cohesion does not appear in this list. Here, I explore how the proposed curriculum reforms align (or do not align) with the NPP’s pledge to inculcate “[s]afety, mutual understanding, trust and rights of all ethnicities and religious groups” (p.127), in their 2024 Election Manifesto.

Language/ethnicity in the present curriculum

The civil war ended over 15 years ago, but our general education system has done little to bring ethnic communities together. In fact, most students still cannot speak in the “second national language” (SNL) and textbooks continue to reinforce negative stereotyping of ethnic minorities, while leaving out crucial elements of our post-independence history.

Although SNL has been a compulsory subject since the 1990s, the hours dedicated to SNL are few, curricula poorly developed, and trained teachers few (Perera, 2025). Perhaps due to unconscious bias and for ideological reasons, SNL is not valued by parents and school communities more broadly. Most students, who enter our Faculty, only have basic reading/writing skills in SNL, apart from the few Muslim and Tamil students who schooled outside the North and the East; they pick up SNL by virtue of their environment, not the school curriculum.

Regardless of ethnic background, most undergraduates seem to be ignorant about crucial aspects of our country’s history of ethnic conflict. The Grade 11 history textbook, which contains the only chapter on the post-independence period, does not mention the civil war or the events that led up to it. While the textbook valourises ‘Sinhala Only’ as an anti-colonial policy (p.11), the material covering the period thereafter fails to mention the anti-Tamil riots, rise of rebel groups, escalation of civil war, and JVP insurrections. The words “Tamil” and “Muslim” appear most frequently in the chapter, ‘National Renaissance,’ which cursorily mentions “Sinhalese-Muslim riots” vis-à-vis the Temperance Movement (p.57). The disenfranchisement of the Malaiyaha Tamils and their history are completely left out.

Given the horrifying experiences of war and exclusion experienced by many of our peoples since independence, and because most students still learn in mono-ethnic schools having little interaction with the ‘Other’, it is not surprising that our undergraduates find it difficult to mix across language and ethnic communities. This environment also creates fertile ground for polarizing discourses that further divide and segregate students once they enter university.

More of the same?

How does Transforming General Education seek to address these problems? The introduction begins on a positive note: “The proposed reforms will create citizens with a critical consciousness who will respect and appreciate the diversity they see around them, along the lines of ethnicity, religion, gender, disability, and other areas of difference” (p.1). Although National Education Goal no. 8 somewhat problematically aims to “Develop a patriotic Sri Lankan citizen fostering national cohesion, national integrity, and national unity while respecting cultural diversity (p. 2), the curriculum reforms aim to embed values of “equity, inclusivity, and social justice” (p. 9) through education. Such buzzwords appear through the introduction, but are not reflected in the reforms.

Learning SNL is promoted under Language and Literacy (Learning Area no. 1) as “a critical means of reconciliation and co-existence”, but the number of hours assigned to SNL are minimal. For instance, at primary level (Grades 1 to 5), only 0.3 to 1 hour is allocated to SNL per week. Meanwhile, at junior secondary level (Grades 6 to 9), out of 35 credits (30 credits across 15 essential subjects that include SNL, history and civics; 3 credits of further learning modules; and 2 credits of transversal skills modules (p. 13, pp.18-19), SNL receives 1 credit (10 hours) per term. Like other essential subjects, SNL is to be assessed through formative and summative assessments within modules. As details of the Grade 9 skills assessment are not provided in the document, it is unclear whether SNL assessments will be included in the ‘Literacy and numeracy test’. At senior secondary level – phase 1 (Grades 10-11 – O/L equivalent), SNL is listed as an elective.

Refreshingly, the policy document does acknowledge the detrimental effects of funding cuts in the humanities and social sciences, and highlights their importance for creating knowledge that could help to “eradicate socioeconomic divisions and inequalities” (p.5-6). It goes on to point to the salience of the Humanities and Social Sciences Education under Learning Area no. 6 (p.12):

“Humanities and Social Sciences education is vital for students to develop as well as critique various forms of identities so that they have an awareness of their role in their immediate communities and nation. Such awareness will allow them to contribute towards the strengthening of democracy and intercommunal dialogue, which is necessary for peace and reconciliation. Furthermore, a strong grounding in the Humanities and Social Sciences will lead to equity and social justice concerning caste, disability, gender, and other features of social stratification.”

Sadly, the seemingly progressive philosophy guiding has not moulded the new curriculum. Subjects that could potentially address social/ethnic cohesion, such as environmental studies, history and civics, are not listed as learning areas at the primary level. History is allocated 20 hours (2 credits) across four years at junior secondary level (Grades 6 to 9), while only 10 hours (1 credit) are allocated to civics. Meanwhile, at the O/L, students will learn 5 compulsory subjects (Mother Tongue, English, Mathematics, Science, and Religion and Value Education), and 2 electives—SNL, history and civics are bunched together with the likes of entrepreneurship here. Unlike the compulsory subjects, which are allocated 140 hours (14 credits or 70 hours each) across two years, those who opt for history or civics as electives would only have 20 hours (2 credits) of learning in each. A further 14 credits per term are for further learning modules, which will allow students to explore their interests before committing to a A/L stream or career path.

With the distribution of credits across a large number of subjects, and the few credits available for SNL, history and civics, social/ethnic cohesion will likely remain on the back burner. It appears to be neglected at primary level, is dealt sparingly at junior secondary level, and relegated to electives in senior years. This means that students will be able to progress through their entire school years, like we did, with very basic competencies in SNL and little understanding of history.

Going forward

Whether the students who experience this curriculum will be able to “resist and respond to hegemonic, divisive forces that pose a threat to social harmony and multicultural coexistence” (p.9) as anticipated in the policy, is questionable. Education policymakers and others must call for more attention to social and ethnic cohesion in the curriculum. However, changes to the curriculum would only be meaningful if accompanied by constitutional reform, abolition of policies, such as the Prevention of Terrorism Act (and its proxies), and other political changes.

For now, our school system remains divided by ethnicity and religion. Research from conflict-ridden societies suggests that lack of intercultural exposure in mono-ethnic schools leads to ignorance, prejudice, and polarized positions on politics and national identity. While such problems must be addressed in broader education reform efforts that also safeguard minority identities, the new curriculum revision presents an opportune moment to move this agenda forward.

(Ramya Kumar is attached to the Department of Community and Family Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Jaffna).

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.

by Ramya Kumar

Features

Top 10 Most Popular Festive Songs

Certain songs become ever-present every December, and with Christmas just two days away, I thought of highlighting the Top 10 Most Popular Festive Songs.

The famous festive songs usually feature timeless classics like ‘White Christmas,’ ‘Silent Night,’ and ‘Jingle Bells,’ alongside modern staples like Mariah Carey’s ‘All I Want for Christmas Is You,’ Wham’s ‘Last Christmas,’ and Brenda Lee’s ‘Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree.’

The following renowned Christmas songs are celebrated for their lasting impact and festive spirit:

* ‘White Christmas’ — Bing Crosby

The most famous holiday song ever recorded, with estimated worldwide sales exceeding 50 million copies. It remains the best-selling single of all time.

* ‘All I Want for Christmas Is You’ — Mariah Carey

A modern anthem that dominates global charts every December. As of late 2025, it holds an 18x Platinum certification in the US and is often ranked as the No. 1 popular holiday track.

Mariah Carey: ‘All I Want for Christmas Is You’

* ‘Silent Night’ — Traditional

Widely considered the quintessential Christmas carol, it is valued for its peaceful melody and has been recorded by hundreds of artistes, most famously by Bing Crosby.

* ‘Jingle Bells’ — Traditional

One of the most universally recognised and widely sung songs globally, making it a staple for children and festive gatherings.

* ‘Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree’ — Brenda Lee

Recorded when Lee was just 13, this rock ‘n’ roll favourite has seen a massive resurgence in the 2020s, often rivaling Mariah Carey for the top spot on the Billboard Hot 100.

* ‘Last Christmas’ — Wham!

A bittersweet ’80s pop classic that has spent decades in the top 10 during the holiday season. It recently achieved 7x Platinum status in the UK.

* ‘Jingle Bell Rock’ — Bobby Helms

A festive rockabilly standard released in 1957 that remains a staple of holiday radio and playlists.

* ‘The Christmas Song (Chestnuts Roasting on an Open Fire)’— Nat King Cole

Known for its smooth, warm vocals, this track is frequently cited as the ultimate Christmas jazz standard.

Wham! ‘Last Christmas’

* ‘It’s the Most Wonderful Time of the Year’ — Andy Williams

Released in 1963, this high-energy big band track is famous for capturing the “hectic merriment” of the season.

* ‘Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer’ — Gene Autry

A beloved narrative song that has sold approximately 25 million copies worldwide, cementing the character’s place in Christmas folklore.

Other perennial favourites often in the mix:

* ‘Feliz Navidad’ – José Feliciano

* ‘A Holly Jolly Christmas’ – Burl Ives

* ‘Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow!’ – Frank Sinatra

Let me also add that this Thursday’s ‘SceneAround’ feature (25th December) will be a Christmas edition, highlighting special Christmas and New Year messages put together by well-known personalities for readers of The Island.

-

Midweek Review7 days ago

Midweek Review7 days agoHow massive Akuregoda defence complex was built with proceeds from sale of Galle Face land to Shangri-La

-

News15 hours ago

News15 hours agoMembers of Lankan Community in Washington D.C. donates to ‘Rebuilding Sri Lanka’ Flood Relief Fund

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoPope fires broadside: ‘The Holy See won’t be a silent bystander to the grave disparities, injustices, and fundamental human rights violations’

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoPakistan hands over 200 tonnes of humanitarian aid to Lanka

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoUnlocking Sri Lanka’s hidden wealth: A $2 billion mineral opportunity awaits

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoBurnt elephant dies after delayed rescue; activists demand arrests

-

Editorial7 days ago

Editorial7 days agoColombo Port facing strategic neglect

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoArmy engineers set up new Nayaru emergency bridge