Features

Moving up the Colonial civil services ladder in the Caribbean and Africa

by Sir. Henry Monck-Mason Moore

Last British Governor of then Ceylon

The writer outlines his career prior to his return to Ceylon

Towards the end of 1921 1 went on leave when I met Miss Benson again in London and we became engaged. She was at the time a very brilliant student at the Royal Academy schools to which she had gone after working in the Slade School. Her marriage to me in December of that year put an end to what might have been a great career as a painter. Since my retirement she had done some serious painting again.

We had to cut our honeymoon short, as I was unexpectedly offered the post of Colonial Secretary, Bermuda. It represented promotion only in status, as the salary attached was less than I was drawing in Ceylon, no official house was provided and no passage allowance. After some 18 months I applied for a transfer, regardless of status, to an appointment in some other Colony where we could live on our pay, and in 1924 I was offered the post of Principal Assistant Secretary, Nigeria, which I accepted.

Though ruinously expensive, our time in Bermuda had its compensations. Prohibition had not been rescinded in America, and three ships a week from New York brought shiploads of its thirsty citizens to the hotels and bars of this popular tourist resort. Among them we met many charming people, though it was impossible to return their hospitality in the sort of boarding house in which we were reduced to live. The old Bermudian families lived in a select social circle of their own. Many of them let their charming old colonial type houses for the American season at highly inflated rentals on which they were able to live in great comfort for the rest of the year.

The Chief Justice, the Colonial Secretary and the Chief of Police were the only three imported officials, and it was difficult, if not impossible to get the House of Assembly to improve their conditions of service. The executive had no representation in the lower house – even the Attorney-General, a Bermudian and member of the Executive Council, had to secure a seat in some constituency, before he could sit and introduce Government bills.

The Legislative Council, the upper house, consisted of the Chief Justice as President, the Colonial Secretary and Receiver-General (Treasury and Customs) as official members with two unofficial members who had won their spurs in the lower house. The Governor was always a soldier and commander of the local garrison. He presided over the Executive Council, but took no part in the debates of either house, his proposals being forwarded to the Legislature by way of “message,” and had no powers, other than those of persuasion, of securing his policy being adopted. Any idea of Colonial Office control was bitterly resented and the Assembly has succeeded in maintaining its virtual independence up to the present day.

For me it was a novel and somewhat exasperating experience to have to plunge so abruptly into the whirlpool of local politics in an island where, because of its very smallness, party feelings were easily aroused and personal rivalries were rampant. In retrospect it was no doubt a useful experience for the more controversial political crises in which I was destined to be involved in Kenya and still later in Ceylon.

In Bermuda the franchise was dependent on a property qualification which was jealously guarded by the old Bermudian families. As a result there was in my time only one coloured member of the House of Assembly, and socially the colour bar was complete. Immigration from the West Indies was closely controlled, and the Bermudian Negroes, mostly descendants of emancipated slaves, were generally employed as domestic servants, carriage drivers – no motor cars were allowed in the island – and dock labourers. The growing of fresh vegetables and the Bermuda Lily was in the hands of specially imported Portuguese, who were skilled market gardeners. The colour question, therefore, in my day had not assumed serious proportions.

Nigeria

In 1924, I accepted the post of Principal Assistant Secretary in the Lagos Secretariat, Nigeria, having refused the appointment of Colonial Secretary, Bahamas, where I knew the conditions were much the same as in Bermuda and the cost of living equally expensive. On arrival, as I have already recorded, I found Sir Hugh Clifford was Governor and Sir Donald Cameron Chief Secretary. When Northern and Southern Nigeria were united in a single administration by Lord Lugard, Sir Donald had been responsible for much of the detailed work behind the scene. He was primarily an office man with Southern Nigerian experience and was not persona grata to the Lieutenant-Governors of the North.

Whether for this or for reasons of economy he was not given the status or salary which his duties and responsibilities deserved. Sir Hugh Clifford on his arrival immediately set up a well-staffed and organized Central Secretariat in Lagos, made Sir Donald Chief Secretary, and gave him equivalent status and salary with the Lieutenant-Governors of Northern and Southern Nigeria. As a result Sir Hugh and Sir Donald worked together in great harmony, and were a formidable team.

Sir Donald absorbed much of Sir Hugh’s administrative experience, but at the same time brought his acid intelligence to bear on Sir Hugh’s more exuberant proposals. Before long Sir Donald was promoted to the Governorship of Tanganyika, and was, succeeded by Sir F. M. Baddeley from Malaya.On the announcement that the Prince of Wales was to visit Nigeria and the West Coast Colonies en route to Cape Town, Sir Hugh entered enthusiastically into the preparation of somewhat grandiose plans for his reception. A reception committee was set up of which I became the secretary, while Lady Clifford, who was in London, kept in touch with the Prince’s staff, at St. James’ Palace.

In the midst of all these preparations Sir Hugh had something in the nature of a nervous breakdown and for six weeks retired up country for a rest to await the arrival of Lady Clifford. At the last moment, owing to an outbreak of smallpox in Lagos, the visit was almost abandoned altogether, but eventually this difficulty was overcome by re-arranging the itinerary so that the visit to Lagos was made after the quarantine period had expired.

As a result Sir Hugh alternated between periods of deep depression and high exaltation, and it was on the latter note that eventually he accompanied the Prince throughout his visit. A contributory factor was that he knew by this time that he was to become Governor of Ceylon, a stepping-stone to the Governorship of Malaya, which had been his life long ambition.During the last few weeks, between the departure of the Prince of Wales and Sir Hugh’s own departure on leave prior to taking up the Ceylon appointment, his behaviour became suggestive of some form of mental instability, and it was reported by some of his friends to the medical authorities that they were apprehensive that he was suffering from delusions.

What steps, if any, were taken to report this to the Colonial Office officially I do not know. In view of the tragic end to his brilliant career when Governor of Malaya, one is left wondering whether this could have been in any way avoided.In 1927 I was promoted to Deputy Chief Secretary in succession to Sir Shenton Thomas, who was appointed Colonial Secretary in the Gold Coast from which he went later to Singapore as Governor and became a Japanese prisoner of war on the fall of Singapore. By that time Sir Graeme Thomson had succeeded Sir Hugh Clifford as Governor of Nigeria, and my wife and I were naturally delighted at again serving under him and Lady Thomson, whom we had known so well in Ceylon.

They had had, I believe, a difficult time in British Guiana, where Sir Graeme had introduced some constitutional reforms in the teeth of much local unofficial opposition. As a result he seemed to have lost some of his early vigour, though he early initiated a new housing scheme for Government servants, which was long overdue. He appointed two committees for Northern and Southern Nigeria and I was fortunate in being appointed Secretary to both. He also took the revolutionary step in those days of appointing a woman member to each. This was a wise move as by that time more and more wives were coming out to join their husbands during their tours of service, which had been prohibited or greatly restricted in the past.

As a result my wife and I had the opportunity of making, extensive tours in the two provinces and seeing something of out-station life, which was a welcome change from the somewhat suburban atmosphere of Lagos. Later Sir Graeme fell seriously ill with an internal haemorrhage, and when I left in 1929 to take up the appointment of Colonial Secretary, Kenya, he was lying in bed in Government House on the danger list. He subsequently recovered but I don’t think he was ever quite the same man again.

Kenya

In 1929 we arrived in Nairobi to find the Governor Sir Edward Grigg in London and my predecessor Sir Edward Denham on leave preparatory to taking up the appointment of Governor of Jamaica. So the Chief Justice, Sir Jacob Bath, was acting as Governor and continued to do so till the return of Sir Edward Grigg. Kenya was in the throes of much political agitation owing to the demand of the Indians to be put on a common roll with the European elected members instead of an Indian communal roll. At the same time the European elected members were pressing for closer union between the territories of Kenya, Uganda, and Tanganyika.

Mr. Amery, the Secretary of State for the Colonies in the Conservative Government, was a strong advocate of such a policy, and had privately instructed Sir Edward Grigg to prepare the ground for it. With the support of Lord Delamere, the leader of the Settlers, an imposing new Government House, designed by Sir Herbert Baker, had been built on lines suitable for the accommodation of a Governor-General of the three territories.

Neither Uganda nor Tanganyika were enthusiastic over this proposal, as they were apprehensive of domination by White Settler opinion. The controversy was referred to London where an Inter-Parliamentary Committee advised against any immediate action without, closing the door to its further consideration in the future. By this time the world economic depression was threatening and Lord Delamere himself realized that the scheme must be put into cold storage till economic conditions were more favourable. With the advent of Lord Passfield as Secretary for the Colonies under the Labour Government, a White Paper was issued which gave the agitation its quietus.

The Indians at first boycotted both the Municipal and Legislative Council elections but eventually accepted a communal role, which enabled them to take their part in municipal and legislative activities. It was in this super-charged atmosphere that I found myself, as, Colonial Secretary, Leader of the Official majority in the Legislative Council, in which I made my first appearance with some trepidation, as neither in Bermuda nor Nigeria did I have any experience of the rough and tumble of parliamentary debate.

Eventually I found my feet and was able to establish friendly relations with all sides of the House despite verbal encounters in the debating chamber. But by this time constitutional controversies were temporarily forgotten in the attempt to grapple with the serious financial position of the Colony owing to the world depression.It was at this time that I first met General Smuts when I sat next to him at a dinner given in his honour on his way to attend the World Economic Conference. Speaking from a few notes scribbled on the back of his menu card, he adroitly side-stepped any local controversial issues and won general applause for his statesmanlike and noncommittal appreciation of the situation. I little thought that I was later to be brought into so much closer association with him during World War II.

Owing to the collapse of world prices the European farmers were in serious straits with the banks calling in mortgages and declining to make advances to meet current expenditure. Some relief was afforded by the Government’s establishment of a Land Bank, and by the discovery of alluvial gold in the Kakamega area; many farmers left their wives to run the farms and went to pan gold themselves. But no substantial gold mining materialized, and this proved only a temporary expedient.

By this time Sir Edward Grigg’s term of office was expiring, and I acted as Governor till the arrival of his successor, Sir Joseph Byrne. His relations with Lord Delamere were strained from the first, and the situation was not made easier by the fact that, although a levy on salaries had been imposed on all Government officers and Government expenditure reduced to a minimum, the financial position of the Colony was still very bad.

Accordingly Lord Moyne was sent out by the Secretary of State to report on the situation. His original term of reference was to review the revenue position and its allocation between European, Indian and native services. The natives paid hut and poll tax but non-natives paid no direct taxation other than certain charges for schools and hospitals. Lord Moyne was later instructed to make recommendations for balancing the Budget and recommended the introduction of income tax for all non-natives.

This gave rise to one of the most heated controversies in Kenya’s history. After the Bill had passed its Second Reading by use of the Official majority, Lord Francis Scott and Col Grogan flew to London to see the Secretary of State, Sir Philip Cunliffe Lister, to gain support to alternative proposals proposed by the European elected members.

They were able to induce the Secretary of State to give their proposals a trial, and the Income Tax Bill was dropped. In the event, as the local government had foreseen, some of their proposals proved unworkable and the remainder failed miserably to produce the revenue required. Eventually, after long delay, agreement was reached to the introduction of Income Tax as an emergency measure. It is still on the statute book !

On Lord Delamere’s death, Lord Francis Scott had become leader of the European elected members. As explained above he had in London secured the last minute approval of the Secretary of State to the shelving of the Income Tax Bill. This was hailed with delight as a defeat of the local government. At this awkward moment Sir Joseph Byrne had to go on leave for health reasons and I was left to carry the baby.It was a highly controversial period and later, after Sir Joseph’s return, Cunliffe-Lister flew out himself to visit Kakamega and meet a deputation of the elected members. Unfortunately he was taken seriously ill and lay for days in Government House before he was out of danger. His visit, therefore, did little to remove the tension, particularly as he was unwilling to provide the financial aid on the lines recommended by the elected members.

By 1934 when I left to become Governor of Sierra Leone, Kenya was slowly emerging from the depression. I was first offered the Governorship of British Guiana. But this I refused on the advice once given to me by Sir Graeme Thomson. He had accepted it himself with enthusiasm as he had had high hopes of developing its largely unexplored interior. But he left it disillusioned, and as my experience in Bermuda, though not in the West Indies, had given me some insight into West Indian conditions, I remembered his advice and declined. Soon after Sierra Leone fell vacant, of which Sir Joseph Byrne had previously been Governor. He advised me to accept, which I did.

It was a difficult choice, as it involved leaving our two young daughters in England. For my wife it meant breaking up our home again, and repeating the experience in Nigeria of spending part of the time with me and part with the children. It is the hard price that the Colonial Servant has to pay, but it is the wife who has to pay the hardest price.

In the event unexpected relief came in 1937 by my appointment as an Under Secretary of State in the Colonial Office. Mr. Ormsby-Gore, later Lord Harlech, initiated the idea of bringing in temporarily a junior Governor into the higher echelons of the Home Civil Service instead of bringing in junior officers – known as “Beachcombers” – to work in the lower ranks. It represented a very considerable financial loss and in our case was only rendered possible by the generosity of my wife’s parents.

During my comparatively brief period in Sierra Leone I was able to lay the foundations of a closer administration of the Protectorate, which was somewhat haphazardly administered through a host of minor chiefs. I sent Mr. Fenton – a most efficient officer – to study the local native administration being set up, particularly among the Ondos in southern Nigeria. He prepared a most useful report and its recommendations were being implemented when I left.

In the past most emphasis had been laid on Freetown itself, where the educated “creoles” – descendants of the original ex slave settlements – held a monopoly of clerical appointments and trading interests in the West Coast. With the spread of education in the Gold Coast and Nigeria local men were taking their place, while the Syrian traders were successfully ousting them. White collared unemployment was becoming a problem in Freetown, and the interests of the Protectorate natives were of secondary importance to the unofficial members of the Legislative Council.

The development of iron ore at Marampa and the discovery of diamonds and some alluvial gold had revolutionary results, as it became clear that on the development of the mineral resources of the Protectorate depended the prosperity of Sierra Leone, rather, than on the precarious export of palm kernels and palm oil. I also with the aid of the Colonial Development Fund had a circular road driven round the Peninsula which proved to be of great value during the war.

Representatives of the Army, Navy and Air Force, arrived to study sites for aerodromes, flying boat bases, and battery extensions and boom-harbour defences, but little progress had been made by the time I left. I appointed Mr. Beoku Betts, the first Creole to become a member of the local legal department. He became, I believe, a good Government servant despite his having previously graced the Opposition benches in the Legislative Council.

Features

Inescapable need to deal with the past

The sudden reemergence of two major incidents from the past, that had become peripheral to the concerns of people today, has jolted the national polity and come to its centre stage. These are the interview by former president Ranil Wickremesinghe with the Al Jazeera television station that elicited the Batalanda issue and now the sanctioning of three former military commanders of the Sri Lankan armed forces and an LTTE commander, who switched sides and joined the government. The key lesson that these two incidents give is that allegations of mass crimes, whether they arise nationally or internationally, have to be dealt with at some time or the other. If they are not, they continue to fester beneath the surface until they rise again in a most unexpected way and when they may be more difficult to deal with.

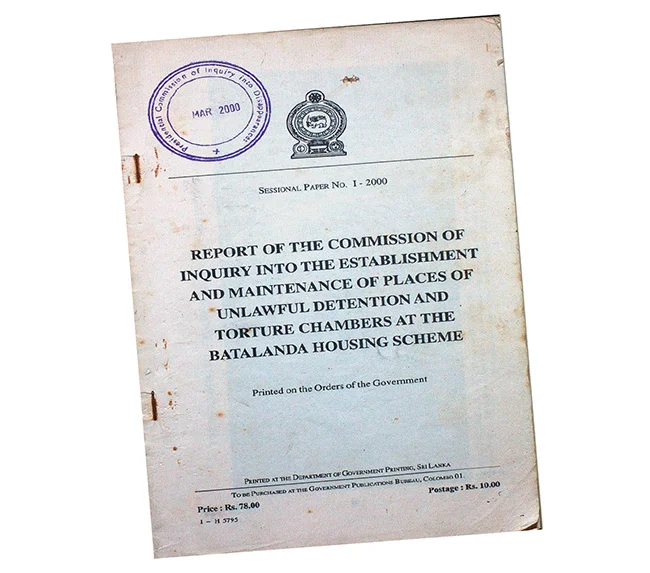

In the case of the Batalanda interrogation site, the sudden reemergence of issues that seemed buried in the past has given rise to conjecture. The Batalanda issue, which goes back 37 years, was never totally off the radar. But after the last of the commission reports of the JVP period had been published over two decades ago, this matter was no longer at the forefront of public consciousness. Most of those in the younger generations who were too young to know what happened at that time, or born afterwards, would scarcely have any idea of what happened at Batalanda. But once the issue of human rights violations surfaced on Al Jazeera television they have come to occupy centre stage. From the day the former president gave his fateful interview there are commentaries on it both in the mainstream media and on social media.

There seems to be a sustained effort to keep the issue alive. The issues of Batalanda provide good fodder to politicians who are campaigning for election at the forthcoming Local Government elections on May 6. It is notable that the publicity on what transpired at Batalanda provides a way in which the outcome of the forthcoming local government elections in the worst affected parts of the country may be swayed. The problem is that the main contesting political parties are liable to be accused of participation in the JVP insurrection or its suppression or both. This may account for the widening of the scope of the allegations to include other sites such as Matale.

POLITICAL IMPERATIVES

The emergence at this time of the human rights violations and war crimes that took place during the LTTE war have their own political reasons, though these are external. The pursuit of truth and accountability must be universal and free from political motivations. Justice cannot be applied selectively. While human rights violations and war crimes call for universal standards that are applicable to all including those being committed at this time in Gaza and Ukraine, political imperatives influence what is surfaced. The sanctioning of the four military commanders by the UK government has been justified by the UK government minister concerned as being the fulfilment of an election pledge that he had made to his constituents. It is notable that the countries at the forefront of justice for Sri Lanka have large Tamil Diasporas that act as vote banks. It usually takes long time to prosecute human rights violations internationally whether it be in South America or East Timor and diasporas have the staying power and resources to keep going on.

In its response to the sanctions placed on the military commanders, the government’s position is that such unilateral decisions by foreign government are not helpful and complicate the task of national reconciliation. It has faced criticism for its restrained response, with some expecting a more forceful rebuttal against the international community. However, the NPP government is not the first to have had to face such problems. The sanctioning of military commanders and even of former presidents has taken place during the periods of previous governments. One of the former commanders who has been sanctioned by the UK government at this time was also sanctioned by the US government in 2020. This was followed by the Canadian government which sanctioned two former presidents in 2023. Neither of the two governments in power at that time took visibly stronger stands.

In addition, resolutions on Sri Lanka have been a regular occurrence and have been passed over the Sri Lankan government’s opposition since 2012. Apart from the very first vote that took place in 2009 when the government promised to take necessary action to deal with the human rights violations of the past, and won that vote, the government has lost every succeeding vote with the margins of defeat becoming bigger and bigger. This process has now culminated in an evidence gathering unit being set up in Geneva to collect evidence of human rights violations in Sri Lanka that is on offer to international governments to use. This is not a safe situation for Sri Lankan leaders to be in as they can be taken before international courts in foreign countries. It is important for Sri Lanka’s sovereignty and dignity as a country that this trend comes to an end.

COMPREHENSIVE SOLUTION

A peaceful future for Sri Lanka requires a multi-dimensional approach that addresses the root causes of conflict while fostering reconciliation, justice, and inclusive development. So far the government’s response to the international pressures is to indicate that it will strengthen the internal mechanisms already in place like the Office on Missing Persons and in addition to set up a truth and reconciliation commission. The difficulty that the government will face is to obtain a national consensus behind this truth and reconciliation commission. Tamil parties and victims’ groups in particular have voiced scepticism about the value of this mechanism. They have seen commissions come and commissions go. Sinhalese nationalist parties are also highly critical of the need for such commissions. As the Nawaz Commission appointed to identify the recommendations of previous commissions observed, “Our island nation has had a surfeit of commissions. Many witnesses who testified before this commission narrated their disappointment of going before previous commissions and achieving nothing in return.”

Former minister Prof G L Peiris has written a detailed critique of the proposed truth and reconciliation law that the previous government prepared but did not present to parliament.

In his critique, Prof Peiris had drawn from the South African truth and reconciliation commission which is the best known and most thoroughly implemented one in the world. He points out that the South African commission had a mandate to cover the entire country and not only some parts of it like the Sri Lankan law proposes. The need for a Sri Lankan truth and reconciliation commission to cover the entire country and not only the north and east is clear in the reemergence of the Batalanda issue. Serious human rights violations have occurred in all parts of the country, and to those from all ethnic and religious communities, and not only in the north and east.

Dealing with the past can only be successful in the context of a “system change” in which there is mutual agreement about the future. The longer this is delayed, the more scepticism will grow among victims and the broader public about the government’s commitment to a solution. The important feature of the South African commission was that it was part of a larger political process aimed to build national consensus through a long and strenuous process of consultations. The ultimate goal of the South African reconciliation process was a comprehensive political settlement that included power-sharing between racial groups and accountability measures that facilitated healing for all sides. If Sri Lanka is to achieve genuine reconciliation, it is necessary to learn from these experiences and take decisive steps to address past injustices in a manner that fosters lasting national unity. A peaceful Sri Lanka is possible if the government, opposition and people commit to truth, justice and inclusivity.

by Jehan Perera

Features

Unleashing Minds: From oppression to liberation

Education should be genuinely ‘free’—not just in the sense of being free from privatisation, but also in a way that empowers students by freeing them from oppressive structures. It should provide them with the knowledge and tools necessary to think critically, question the status quo, and ultimately liberate themselves from oppressive systems.

Education should be genuinely ‘free’—not just in the sense of being free from privatisation, but also in a way that empowers students by freeing them from oppressive structures. It should provide them with the knowledge and tools necessary to think critically, question the status quo, and ultimately liberate themselves from oppressive systems.

Education as an oppressive structure

Education should empower students to think critically, challenge oppression, and envision a more just and equal world. However, in its current state, education often operates as a mechanism of oppression rather than liberation. Instead of fostering independent thinking and change, the education system tends to reinforce the existing power dynamics and social hierarchies. It often upholds the status quo by teaching conformity and compliance rather than critical inquiry and transformation. This results in the reproduction of various inequalities, including economic, racial, and social disparities, further entrenching divisions within society. As a result, instead of being a force for personal and societal empowerment, education inadvertently perpetuates the very systems that contribute to injustice and inequality.

Education sustaining the class structure

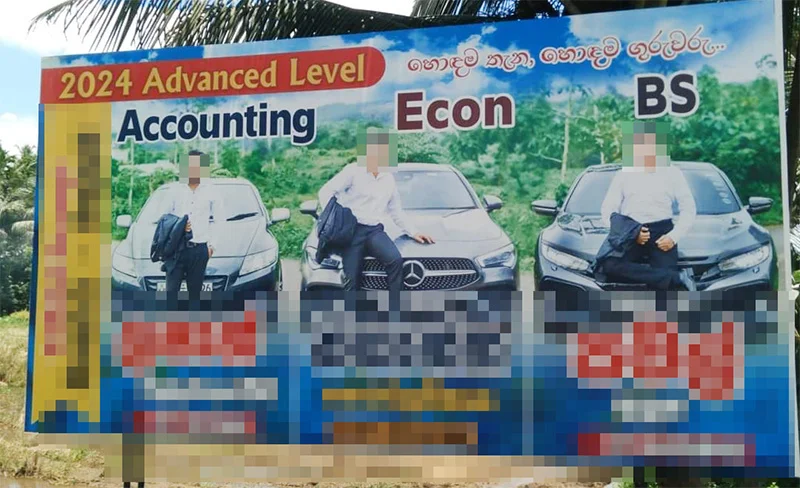

Due to the widespread privatisation of education, the system continues to reinforce and sustain existing class structures. Private tuition centres, private schools, and institutions offering degree programmes for a fee all play a significant role in deepening the disparities between different social classes. These private entities often cater to the more affluent segments of society, granting them access to superior education and resources. In contrast, students from less privileged backgrounds are left with fewer opportunities and limited access to quality education, exacerbating the divide between the wealthy and the underprivileged. This growing gap in educational access not only limits social mobility but also perpetuates a cycle where the privileged continue to secure better opportunities while the less fortunate struggle to break free from the constraints of their socio-economic status.

Gender Oppression

Education subtly perpetuates gender oppression in society by reinforcing stereotypes, promoting gender insensitivity, and failing to create a gender-sensitive education system. And some of the policymakers do perpetuate this gender insensitive education by misinforming people. In a recent press conference, one of the former members of Parliament, Wimal Weerawansa, accused gender studies of spreading a ‘disease’ among students. In the year 2025, we are still hearing such absurdities discouraging gender studies. It is troubling and perplexing to hear such outdated and regressive views being voiced by public figures, particularly at a time when societies, worldwide, are increasingly embracing diversity and inclusion. These comments not only undermine the importance of gender studies as an academic field but also reinforce harmful stereotypes that marginalise individuals who do not fit into traditional gender roles. As we move forward in an era of greater social progress, such antiquated views only serve to hinder the ongoing work of fostering equality and understanding for all people, regardless of gender identity.

Students, whether in schools or universities, are often immersed in an educational discourse where gender is treated as something external, rather than an essential aspect of their everyday lives. In this framework, gender is framed as a concern primarily for “non-males,” which marginalises the broader societal impact of gender issues. This perspective fails to recognise that gender dynamics affect everyone, regardless of their gender identity, and that understanding and addressing gender inequality is crucial for all individuals in society.

A poignant example of this issue can be seen in the recent troubling case of sexual abuse involving a medical doctor. The public discussion surrounding the incident, particularly the media’s decision to disclose the victim’s confidential statement, is deeply concerning. This lack of respect for privacy and sensitivity highlights the pervasive disregard for gender issues in society.

What makes this situation even more alarming is that such media behaviour is not an isolated incident, but rather reflects a broader pattern in a society where gender sensitivity is often dismissed or ignored. In many circles, advocating for gender equality and sensitivity is stigmatised, and is even seen as a ‘disease’ or a disruptive force to the status quo. This attitude contributes to a culture where harmful gender stereotypes persist, and where important conversations about gender equity are sidelined or distorted. Ultimately, this reflects the deeper societal need for an education system that is more attuned to gender sensitivity, recognising its critical role in shaping the world students will inherit and navigate.

To break free from these gender hierarchies there should be, among other things, a gender sensitive education system, which does not limit gender studies to a semester or a mere subject.

Ragging

The inequality that persists in class and regional power structures (Colombo and non-Colombo division) creeps into universities. While ragging is popularly seen as an act of integrating freshers into the system, its roots lie in the deeply divided class and ethno-religious divisions within society.

In certain faculties, senior students may ask junior female students to wear certain fabrics typically worn at home (cheetta dresses) and braid their hair into two plaits, while male students are required to wear white, long-sleeved shirts without belts. Both men and women must wear bathroom slippers. These actions are framed as efforts to make everyone equal, free from class divisions. However, these gendered and ethicised practices stem from unequal and oppressive class structures in society and are gradually infiltrating university culture as mechanisms of oppression.The inequality that persists in gradually makes its way into academic institutions, particularly universities.

These practices are ostensibly intended to create a sense of uniformity and equality among students, removing visible markers of class distinction. However, what is overlooked is that these actions stem from deeply ingrained and unequal social structures that are inherently oppressive. Instead of fostering equality, they reinforce a system where hierarchical power dynamics in the society—rooted in class, gender, and region—are confronted with oppression and violence which is embedded in ragging, creating another system of oppression.

Uncritical Students

In Sri Lanka, and in many other countries across the region, it is common for university students to address their lecturers as ‘Sir’ and ‘Madam.’ This practice is not just a matter of politeness, but rather a reflection of deeply ingrained societal norms that date back to the feudal and colonial eras. The use of these titles reinforces a hierarchical structure within the educational system, where authority is unquestioned, and students are expected to show deference to their professors.

Historically, during colonial rule, the education system was structured around European models, which often emphasised rigid social distinctions and the authority of those in power. The titles ‘Sir’ and ‘Madam’ served to uphold this structure, positioning lecturers as figures of authority who were to be respected and rarely challenged. Even after the end of colonial rule, these practices continued to permeate the education system, becoming normalised as part of the culture.

This practice perpetuates a culture of obedience and respect for authority that discourages critical thinking and active questioning. In this context, students are conditioned to see their lecturers as figures of unquestionable authority, discouraging dialogue, dissent, or challenging the status quo. This hierarchical dynamic can limit intellectual growth and discourage students from engaging in open, critical discussions that could lead to progressive change within both academia and society at large.

Unleashing minds

The transformation of these structures lies in the hands of multiple parties, including academics, students, society, and policymakers. Policymakers must create and enforce policies that discourage the privatisation of education, ensure equal access for all students, regardless of class dynamics, gender, etc. Education should be regarded as a fundamental right, not a privilege available only to a select few. Such policies should also actively promote gender equality and inclusivity, addressing the barriers that prevent women, LGBTQ+ individuals, and other marginalised genders from accessing and succeeding in education. Practices that perpetuate gender inequality, such as sexism, discrimination, or gender-based violence, need to be addressed head-on. Institutions must prioritise gender studies and sensitivity training to cultivate an environment of respect and understanding, where all students, regardless of gender, feel safe and valued.

At the same time, the micro-ecosystems of hierarchy within institutions—such as maintaining outdated power structures and social divisions—must be thoroughly examined and challenged. Universities must foster environments where critical thinking, mutual respect, and inclusivity—across both class and gender—are prioritised. By creating spaces where all minds can flourish, free from the constraints of entrenched hierarchies, we can build a more equitable and intellectually vibrant educational system—one that truly unleashes the potential of all students, regardless of their social background.

(Anushka Kahandagamage is the General Secretary of the Colombo Institute for Human Sciences)

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.

By Anushka Kahandagamage

Features

New vision for bassist Benjy

It’s a known fact that whenever bassist Benjy Ranabahu booms into action he literally lights up the stage, and the exciting news I have for music lovers, this week, is that Benjy is coming up with a new vision.

One thought that this exciting bassist may give the music scene a layoff, after his return from the Seychelles early this year.

At that point in time, he indicated to us that he hasn’t quit the music scene, but that he would like to take a break from the showbiz setup.

“I’m taking things easy at the moment…just need to relax and then decide what my future plans would be,” he said.

However, the good news is that Benjy’s future plans would materialise sooner than one thought.

Yes, Benjy is putting together his own band, with a vision to give music lovers something different, something dynamic.

He has already got the lineup to do the needful, he says, and the guys are now working on their repertoire.

The five-piece lineup will include lead, rhythm, bass, keyboards and drums and the plus factor, said Benjy, is that they all sing.

A female vocalist has also been added to this setup, said Benjy.

“She is relatively new to the scene, but with a trained voice, and that means we have something new to offer music lovers.”

The setup met last week and had a frank discussion on how they intend taking on the music scene and everyone seems excited to get on stage and do the needful, Benjy added.

Benjy went on to say that they are now spending their time rehearsing as they are very keen to gel as a team, because their skills and personalities fit together well.

“The guys I’ve got are all extremely talented and skillful in their profession and they have been around for quite a while, performing as professionals, both here and abroad.”

Benjy himself has performed with several top bands in the past and also had his own band – Aquarius.

Aquarius had quite a few foreign contracts, as well, performing in Europe and in the Middle East, and Benjy is now ready to do it again!

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoSri Lanka’s eternal search for the elusive all-rounder

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoCelebrating 25 Years of Excellence: The Silver Jubilee of SLIIT – PART I

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoGnanasara Thera urged to reveal masterminds behind Easter Sunday terror attacks

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoCEB calls for proposals to develop two 50MW wind farm facilities in Mullikulam

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoAIA Higher Education Scholarships Programme celebrating 30-year journey

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoNotes from AKD’s Textbook

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoBid to include genocide allegation against Sri Lanka in Canada’s school curriculum thwarted

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoComBank crowned Global Finance Best SME Bank in Sri Lanka for 3rd successive year