Features

Sri Lanka’s gas tragedy: the untold story

By Deshai Botheju, Ph.D.

M.Sc.Tech.(Norway), M.Sc., B.Sc.Eng. (1st Hons., UoM), AIChE, AMIE(SL)

deshaibotheju@acses.org

Recent explosions and gas leak accidents related to domestic LP gas cylinders have created an environment of fear, anxiety, and social unrest throughout the country. More than 400 explosions and gas leak incidents have been reported during the first week of December 2021. In addition, a large number of observations have been made with respect to leaking gas cylinder valves.

The reported accidents and incidents can be divided into four major categories: (a) Sudden gas explosions inside houses and building, (b) Sudden explosions associated with the gas cooker, (c) Major gas leaks and resulting damages associated with the regulator and the hoses, (d) Minor gas leaks from the cylinder valve, regulator, or the hoses. The number of accidents reported during a single week has far exceeded the typical gas-related accidents happening within a typical year. Something must have gone terribly wrong for Sri Lankan LP gas consumers. Unconfirmed reports now indicate potential deaths, associated with some of these gas explosion accidents.

What is LPG?

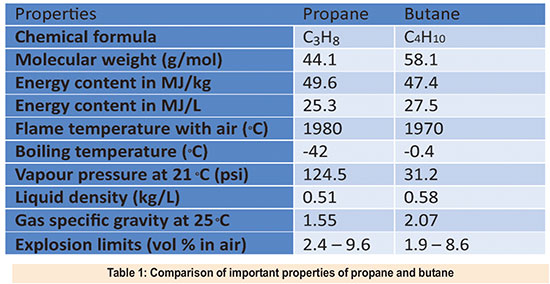

Liquefied Petroleum Gas, abbreviated LPG, is an energy carrier derived during crude oil refining or natural gas processing. In petroleum industry terminology these are called gas condensates and are byproducts often generated during the production of liquid fuels (gasoline, diesel, and kerosene) or natural gas (methane). The key components of typical LP gas are propane (an alkane gas containing three carbon atoms – C3H8) and butane (an alkane gas containing four carbon atoms – C4H10). In addition, small amounts of propylene, methane, pentane and other minor constituents can be present. LP gases do not originally have a clearly recognizable distinct odour. Therefore, in order to identify any gas leaks, methyl mercaptan (CH3SH), or a similar odour generating component, is added to LP gas before commercial use. Table 1 provides a useful comparison between propane and butane, with respect to key physical or chemical properties.

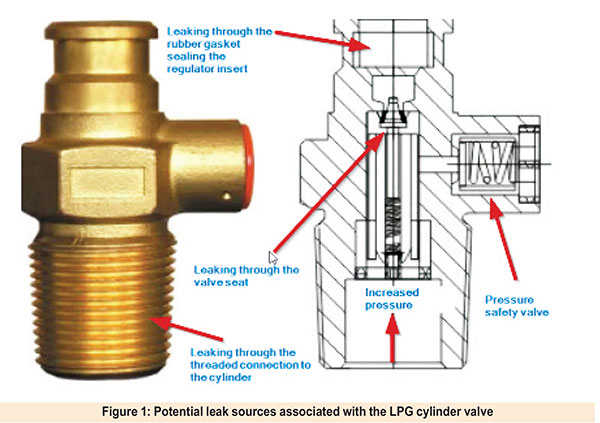

Depending on the refinery process, or intended use, LP gas can have a widely varying propane and butane composition. Under normal atmospheric pressure, butane has a higher boiling point of minus 0.5 degrees Celsius (-0.5) compared to propane’s minus 42 degrees Celsius (-42) boiling point. That means in colder climates, where the ambient temperature could go below 0 degrees Celsius, the LP gas must mostly contain propane in order to use that as a fuel gas (otherwise it wouldn’t flow as a gas, as butane would remain in the cylinder as a liquid). Therefore, the butane content is greatly reduced in LP gas used in colder climate countries, typically less than five percent of the volume. For tropical countries, like Sri Lanka, having a high butane content is just fine, as the year-round temperature is almost always above zero degrees Celsius (except for some rare occasions in locations at higher altitudes). Further, butane is a much safer gas to use. This is due to its much lower vapour pressure (31 pound per square inch) compared to that of propane (124.5 psi). Therefore, the containment integrity requirements shall be much stricter for propane use, compared to butane. (figure I)

Composition changes and pressure effects

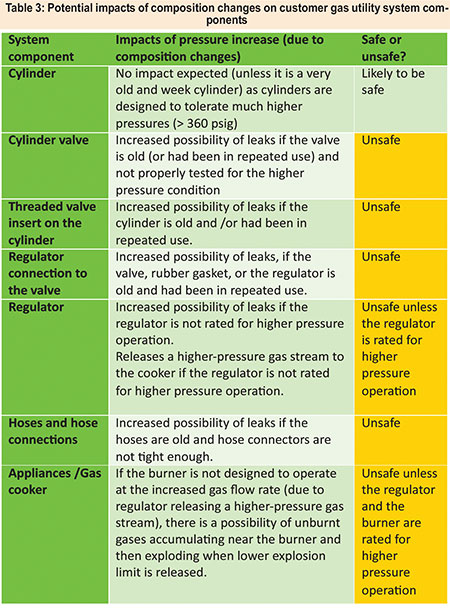

Unlike compressed gas cylinders, LP gas cylinders are not filled with 100 percent gas. Instead, a new cylinder would contain the liquids, hence the name LP gas, to about 85 percent volume. Only the remaining 15 percent ullage volume (the volume left empty in a tank for the liquid to expand) contains actual gas. These two phases (liquid and gas) are in equilibrium. The pressure within this gas filled ullage is the equilibrium pressure of the corresponding liquid mixture (of propane and butane). This equilibrium pressure can be predicted based on the ambient temperature and the composition of the liquid phase. Table 2 provides the values of these equilibrium pressures (in pounds per square inch gauge or psig) for different propane-butane mixtures at the temperature of 32 degrees Celsius (which is quite close to the typical ambient temperature in Sri Lanka). (Figure II)

Unlike compressed gas cylinders, LP gas cylinders are not filled with 100 percent gas. Instead, a new cylinder would contain the liquids, hence the name LP gas, to about 85 percent volume. Only the remaining 15 percent ullage volume (the volume left empty in a tank for the liquid to expand) contains actual gas. These two phases (liquid and gas) are in equilibrium. The pressure within this gas filled ullage is the equilibrium pressure of the corresponding liquid mixture (of propane and butane). This equilibrium pressure can be predicted based on the ambient temperature and the composition of the liquid phase. Table 2 provides the values of these equilibrium pressures (in pounds per square inch gauge or psig) for different propane-butane mixtures at the temperature of 32 degrees Celsius (which is quite close to the typical ambient temperature in Sri Lanka). (Figure II)

As can be seen from Table 2, at 32 oC temperature, a mixture of 80 percent butane and 20 percent propane has an equilibrium pressure of 53.6 psig. This was the composition used in Sri Lanka for a long time. All appliances (including gas cookers), pressure regulators, hoses, hose connectors, gas cylinder valves and cylinders have been accustomed to this pressure condition. In other words, our consumer gas utility system has been calibrated at this pressure condition. Nevertheless, gas cylinders themselves are manufactured to tolerate a much higher pressure.

If the butane-propane composition is suddenly changed to 50 % butane and 50 % propane, now the increased propane content leads to a much higher equilibrium pressure of 89.4 psig. It is obvious that this is a very significant pressure increase from the previous condition.

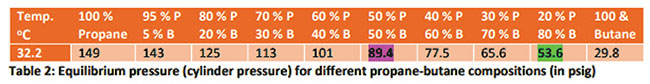

Containment integrity

Increased propane content leads to a significant increase in gas pressure inside the cylinder. This is because propane has a much higher equilibrium vapour pressure compared to butane (see Table 1). Now, the whole utility system on the part of the customers faces a containment integrity problem. In other words, gas leaks are likely to happen from many of the system components. Table 3 elaborates potential impacts of this pressure increase on different system components. Figure 1 further illustrates potential leak sources and pathways associated with the gas cylinder valve. (Figures III and IV)

What happens during a gas leak?

Propane and butane are flammable and combustible gases, when mixed with air (or oxygen). Within the approximate volume percentages of 2 to 10 percent (within LEL- Lower explosive limit and UEL – Upper explosive limit), these gases can create an explosive gas mixture when exposed to air; see Table 1. Outside of this volume percentage range, the gas would not ignite. However, at higher gas concentrations, the gas cloud can still pose an asphyxiation hazard to humans as it displaces breathable oxygen in air.

Propane and butane are flammable and combustible gases, when mixed with air (or oxygen). Within the approximate volume percentages of 2 to 10 percent (within LEL- Lower explosive limit and UEL – Upper explosive limit), these gases can create an explosive gas mixture when exposed to air; see Table 1. Outside of this volume percentage range, the gas would not ignite. However, at higher gas concentrations, the gas cloud can still pose an asphyxiation hazard to humans as it displaces breathable oxygen in air.

Even a minor gas leak in the cylinder valve, regulator, or any other component (see Table 3 and Figure 1) can lead to the accumulation of the gas inside a building, over several hours. Note that both propane and butane gases are higher in density compared to air (heavier than air; see specific gravity values shown in Table 1). Which means, when a gas leak occurs the explosive gas cloud accumulates close to ground level (rather than moving upward and dissipating). This situation is more likely to occur at night when doors and windows are closed, with consequently little or no ventilation. If the leaked cloud of gas reaches the concentration of LEL within that surrounding (for example a kitchen), then it is a bomb waiting to be triggered at any time. The only thing required is a small spark, which may occur when an electrical switch makes contact (on or off), or even due to static electricity present in the atmosphere, or due to an actual flame such as lighting a match. At that moment, an explosive combustion reaction occurs within the flammable gas cloud and the energy released is transmitted as a pressure wave accompanied often by a fireball. This is a typical atmospheric gas cloud explosion. Secondary damage can occur due to projectiles (broken glass for example), prolonged fires, collapsing roofs and walls.

Change management failure

Changing an existing LP gas composition without a detailed safety assessment is an act of sheer negligence bordering on absurdity. It’s a fundamental process engineering principle to follow a comprehensive Management of Change (MoC) protocol before making this kind of, or even far less consequential, change to a product, process, or an operating procedure. Even a Process Engineering Trainee can explain this to production management. As part of an MoC process, it is absolutely necessary to conduct a dedicated risk assessment or a standard safety study such as ‘HAZards and Operability’ (HAZOP). Had such HAZOP been conducted in this case, many of the problems we have indicated in Table 3 could have been identified in advance, avoiding calamity in consequence.

Cost factor and energy contents

The heat energy contents of propane and butane are respectively 49.58 and 47.39 megajoules per kilogram (MJ/kg). However, the density of liquid propane and butane are 0.51 and 0.58 kilograms per litre (kg/L) respectively. That means due to the lower density of propane compared to butane, propane has a slightly lower energy content when based on volume (25.3 and 27.5 MJ/L respectively). Propane burns with a slightly higher flame temperature compared to butane (1980 vs 1970 oC). In certain gas burners, propane could burn with slightly higher efficiency compared to butane (with less deposition of carbon).

If calculated based on the heat energy content delivered (measured by BTU-British Thermal Units), propane is often a cheaper energy commodity compared to butane in the world energy market. Therefore, an LP gas mixture rich in propane can be cheaper. LP gases with more propane are also easier to procure. While per BTU price is cheaper, if calculated based on metric ton price, one can be misled to believe that propane is more expensive than butane. This becomes a false assumption if all gas pricing and market economics are based on the value of BTUs (energy) delivered to the customer (customer is made to pay for the heat energy content delivered to them, and not for the weight of the gas). Also note that the exact price of a certain LPG shipment can be very different from the typical spot prices prevailing in the world energy market.

Safety culture issue

Every organisation has a certain safety culture. Without going into detailed academic definitions of the safety culture concept, we can still try to understand different characteristics of good (positive) safety cultures in comparison to bad (negative) safety cultures.

In a good safety culture Management of Change protocols are always followed; when an accident or an incident occurs, it will always be investigated to the fullest extent and all lessons to be earned are extracted; transparency and honesty are always maintained; instead of finger pointing, their own faults are admitted; no attempts are made at concealing information; safety is always given priority over marginal economic gains. In contrast, the complete opposite of these is to be expected of an organisation with a negative safety culture.

Investigation and compensation

Any investigation into the recent series of unfortunate gas related accidents in Sri Lanka must not stop at merely identifying plausible physical causes. Such investigation must definitely look deeper into related organisational factors, and make necessary recommendations to bring about much needed organisational reforms in the form of enhancing safety culture. In addition, more systematic safety management requirements and stricter regulatory reforms must be recommended to avoid repetition of this kind of ‘organizationally rooted accidents’. Failing to do so may lead to greater disasters of higher magnitude in future. Prompt compensation to those who faced harm must be a priority. Even more urgent is to recall every single gas cylinder delivered with hazardous pressure conditions, irrespective of whether the gas has been used or not. As explained before, LP gas cylinders will retain the same high pressure condition until the last drop of liquid is vaporised. Therefore, unused as well as almost fully used gas cylinders will pose the same level of leaking hazard.

(Facts presented in this article are based on information available on the public domain. The analyses and opinions are based on the author’s experience in the industry, and do not reflect the opinions of any institution.)

Features

The Great and Little Traditions and Sri Lankan Historiography

Power, Culture, and Historical Memory:

History, broadly defined, is the study of the past. It is a crucial component of the production and reproduction of culture. Studying every past event is neither feasible nor useful. Therefore, it is necessary to be selective about what to study from the countless events in the past. Deciding what to study, what to ignore, how to study, and how deeply to go into the past is a conscious choices shaped by various forms of power and authority. If studying the past is a main element of the production and reproduction of culture and History is its product, can a socially and culturally divided society truly have a common/shared History? To what extent does ‘established’ or ‘authentic’ History reflect the experiences of those remained outside the political, economic, social, and cultural power structures? Do marginalized groups have their own histories, distinct from dominant narratives? If so, how do these histories relate to ‘established’ History? Historiography today cannot ignore these questions, as they challenge the very notion of truth in History. Due to methodological shifts driven by post-positivist critiques of previously accepted assumptions, the discipline of history—particularly historiography—has moved into a new epistemological terrain.

The post-structuralism and related philosophical discourses have necessitated a critical reexamination of the established epistemological core of various social science disciplines, including history. This intellectual shift has led to a blurring of traditional disciplinary boundaries among the social sciences and the humanities. Consequently, concepts, theories, and heuristic frames developed in one discipline are increasingly being incorporated into others, fostering a process of cross-fertilization that enriches and transforms scholarly inquiry

In recent decades, the discipline of History has broadened its scope and methodologies through interactions with perspectives from the Social Sciences and Humanities. Among the many analytical tools adopted from other disciplines, the Great Tradition and Little Tradition have had a significant impact on historical methodology. This article examines how these concepts, originally developed in social anthropology, have been integrated into Sri Lankan historiography and assesses their role in deepening our understanding of the past.

The heuristic construct of the Great and Little Traditions first emerged in the context of US Social Anthropology as a tool/framework for identifying and classifying cultures. In his seminal work Peasant society and culture: an anthropological approach to civilization, (1956), Robert Redfield introduced the idea of Great and Little Traditions to explain the dual structure of cultural expression in societies, particularly in peasant communities that exist within larger civilizations. His main arguments can be summarized as follows:

a) An agrarian society cannot exist as a fully autonomous entity; rather, it is just one dimension of the broader culture in which it is embedded. Therefore, studying an agrarian society in isolation from its surrounding cultural context is neither possible nor meaningful.

b) Agrarian society, when views in isolation, is a ‘half society’, representing a partial aspect/ one dimension of the broader civilization in which it exits. In that sense, agrarian civilization is a half civilization. To fully understand agrarian society—and by extension, agrarian civilization—it is essential to examine the other half that contribute to the whole.

c) Agrarian society was shaped by the interplay of two cultural traditions within a single framework: the Great Tradition and the Little Tradition. These traditions together provided the unity that defined the civilization embedded in agrarian society.

d) The social dimensions of these cultural traditions would be the Great Society and the Little Society.

e) The Great Culture encompasses the cultural framework of the Great Society, shaped by those who establish its norms. This group includes the educated elite, clergy, theologians, and literati, whose discourse is often regarded as erudite and whose language is considered classical.

f) The social groups excluded from the “Great Society”—referred to as the “Little Society”—have their own distinct traditions and culture. The “Great Tradition” represents those who appropriate society’s surplus production, and its cultural expressions reflect this dominance. In contrast, the “Little Tradition” belongs to those who generate surplus production. While the “Great Tradition” is inherently tied to power and authority, the “Little Tradition” is not directly connected to them.

g) According to Robert Redfield, the Great and Little Traditions are not contradictory but rather distinct cultural elements within a society. The cultural totality of peasant society encompasses both traditions. As Redfield describes, they are “two currents of thought and action, distinguishable, yet overflowing into and out of each other.” (Redfield, 1956).

At the time Redfield published his book Peasant Society and Culture: an Anthropological Approach to Civilization (1956), the dominant analytical framework for studying non-Western societies was modernization theory. This perspective, which gained prominence in the post-World War II era, was deeply influenced by the US geopolitical concerns. Modernization theory became a guiding paradigm shaping research agendas in anthropology, sociology, political science, and development studies in US institutions of higher learning,

Modernization theory viewed societies as existing along a continuum between “traditional” and “modern” stages, with Western industrialized nations positioned near the modern end. Scholars working within this framework argued that economic growth, technological advancement, urbanization, and the rationalization of social structures drive traditional societies toward modernization. The theory often emphasized Western-style education, democratic institutions, and capitalist economies as essential components of this transition.

While engaging with aspects of modernization theory, Redfield offered a more nuanced perspective on non-Western societies. His concept of the “folk-urban continuum” challenged rigid dichotomies between tradition and modernity, proposing that social change occurs through complex interactions between rural and urban ways of life rather than through the simple replacement of one by the other.

The concepts of the Great and Little Traditions gained prominence in Sri Lankan social science discourse through the works of Gananath Obeyesekere, the renowned sociologist who recently passed away. In his seminal research essay, The Great Tradition and the Little in the Perspective of Sinhalese Buddhism (Journal of Asian Studies, 22, 1963), Gananath Obeyesekere applied and adapted this framework to examine key aspects of Sinhalese Buddhism in Sri Lanka. While Robert Redfield originally developed the concept in the context of agrarian societies, Obeyesekere employed it specifically to analyze Sinhala Buddhist culture, highlighting significant distinctions between the two approaches.

He identifies a phenomenon called ‘Sinhala Buddhism’, which represents a unique fusion of religious and cultural traditions: the Great Tradition (Maha Sampradaya) and the Little Traditions (Chuula Sampradaya). To fully grasp the essence of Sinhala Buddhism, it is essential to understand both of these dimensions and their interplay within society.

The Great Tradition represents the formal, institutionalized aspect of Buddhism, centered on the Three Pitakas and other classical doctrinal texts and commentaries of Theravāda Buddhism. It embodies the orthodoxy of Sinhala Buddhism, emphasizing textual authority, philosophical depth, and ethical conduct. Alongside this exists another dimension of Sinhala Buddhism known as the Little (Chuula) Tradition. This tradition reflects the popular, localized, and ritualistic expressions of Buddhism practiced by laypeople. It encompasses folk beliefs, devotional practices (Bali, Thovil), deity veneration, astrology, and rituals (Hadi and Huunium) aimed at securing worldly benefits. Unlike the doctrinally rigid Great Tradition, the Little Tradition is fluid, adaptive, and shaped by indigenous customs, ancestral practices, and even elements of Hinduism. These Sinhala Buddhist cultural practices are identified as ‘Lay-Buddhism’. Gananath Obeyesekera’s concepts and perspectives on Buddhist culture and society contributed to fostering an active intellectual discourse in society. However, the discussion on the concept of Great and Little Traditions remained largely within the domain of social anthropology.

The scholarly discourse on the concepts of Great and Little Tradition gained new socio-political depth through the work of Newton Gunasinghe, a distinguished Sri Lankan sociologist. He applied these concepts to the study of culture and socio-economic structures in the Kandyan countryside, reframing them in terms of production relations. Through his extensive writings and public lectures, Gunasinghe reinterpreted the Great and Little Tradition framework to explore the interconnections between economy, society, and culture.

Blending conventional social anthropology approach with Marxist analyses of production relations and Gramscian perspectives on culture and politics, he offered a nuanced understanding of these dynamics. In the context of our discussion, his key insights on culture, society, and modes of production can be summarized as follows.

a. The social and economic relations of the central highlands under the Kandyan Kingdom, the immediate pre-colonial social and economic order, were his focus. His analysis did not cover to the hydraulic Civilization of Sri Lanka.

b. He explored the organic and dialectical relationship between culture, forces of production, and modes of production. Drawing on the concepts of Antonio Gramsci and Louis Althusser, he examined how culture, politics, and the economy interact, identifying the relationship between cultural formations and production relations

c. Newton Gunasinghe’s unique approach to the concepts of Great Culture and Little Culture lies in his connection of cultural formations to forces and relations of production. He argues that the relationship between a society’s structures and its superstructures is both dialectical and interpenetrative.

d. He observed that during the Kandyan period, the culture associated with the Little Tradition prevailed, rather than the culture linked to the Great Tradition.

e. The limitations of productive forces led to minimal surplus generation, with a significant portion allocated to defense. The constrained resources sustained only the Little Tradition. Consequently, the predominant cultural mode in the Kandyan Kingdom was, broadly speaking, the Little Tradition.

(To be continued)

by Gamini Keerawella

Features

Celebrating 25 Years of Excellence: The Silver Jubilee of SLIIT – II

Founded in 1999, with its main campus in Malabe and multiple centres across the country—including Metro Campus (Colombo), Matara, Kurunegala, Kandy (Pallekele), and Jaffna (Northern Uni)—SLIIT provides state-of-the-art facilities for students, now celebrating 25 years of excellence in 2025.

Founded in 1999, with its main campus in Malabe and multiple centres across the country—including Metro Campus (Colombo), Matara, Kurunegala, Kandy (Pallekele), and Jaffna (Northern Uni)—SLIIT provides state-of-the-art facilities for students, now celebrating 25 years of excellence in 2025.

Kandy Campus

SLIIT is a degree-awarding higher education institute authorised and approved by the University Grants Commission (UGC) and Ministry of Higher Education under the University Act of the Government of Sri Lanka. SLIIT is also the first Sri Lankan institute accredited by the Institution of Engineering & Technology, UK. Further, SLIIT is also a member of the Association of Commonwealth Universities (ACU) and the International Association of Universities (IAU).

Founded in 1999, with its main campus in Malabe and multiple centres across the country—including Metro Campus (Colombo), Matara, Kurunegala, Kandy (Pallekele), and Jaffna (Northern Uni)—SLIIT provides state-of-the-art facilities for students, now celebrating 25 years of excellence in 2025.

Since its inception, SLIIT has played a pivotal role in shaping the technological and educational landscape of Sri Lanka, producing graduates who have excelled in both local and global arenas. This milestone is a testament to the institution’s unwavering commitment to academic excellence, research, and industry collaboration.

Summary of SLIIT’s

History and Status

Sri Lanka Institute of Information Technology (SLIIT) operates as a company limited by guarantee, meaning it has no shareholders and reinvests all surpluses into academic and institutional development.

* Independence from Government: SLIIT was established in 1999 as an independent entity without government ownership or funding, apart from an initial industry promotion grant from the Board of Investment (BOI).

* Mahapola Trust Fund Involvement & Malabe Campus: In 2000, the Mahapola Trust Fund (MTF) agreed to support SLIIT with funding and land for the Malabe Campus. In 2015, SLIIT fully repaid MTF with interest, ending financial ties.

* True Independence (2017-Present): In 2017, SLIIT was officially delisted from any government ministry, reaffirming its status as a self-sustaining, non-state higher education institution.

Today, SLIIT is recognised for academic excellence, global collaborations, and its role in producing IT professionals in Sri Lanka

.A Journey of Growth and Innovation

SLIIT began as a pioneering institution dedicated to advancing information technology education in Sri Lanka. Over the past two and a half decades, it has expanded its academic offerings, establishing itself as a multidisciplinary university with programmess in engineering, business, architecture, and humanities, in addition to IT. The growth of SLIIT has been marked by continuous improvement in infrastructure, faculty development, and curriculum enhancement, ensuring that students receive world-class education aligned with industry needs.

Looking Ahead: The Next 25 Years

As SLIIT celebrates its Silver Jubilee, the institution looks forward to the future with a renewed commitment to excellence. With advancements in technology, the rise of artificial intelligence, and the increasing demand for skilled professionals, SLIIT aims to further expand its academic offerings, enhance research capabilities, and continue fostering a culture of innovation. The next 25 years promise to be even more transformative, as the university aspires to make greater contributions to national and global progress.

Sports Achievements:

A Legacy of Excellence

SLIIT has not only excelled in academics but has also built a strong reputation in sports. Over the years, the university has actively promoted athletics and competitive sports by organising inter-university and inter-school competitions, fostering a culture of teamwork, discipline, and resilience. SLIIT teams have secured victories in national and inter-university competitions across various sports, including cricket, basketball, badminton, rugby, football, swimming, and athletics. SLIIT’s sports achievements reflect its dedication to holistic student development, encouraging students to excel beyond the classroom.

Kings of the pool!

Once again, our swimmers have brought glory to SLIIT by emerging as champions at the Asia Pacific Institute of Information and Technology Extravaganza Swimming Championship 2024. They won the Men’s, Women’s, and Overall Championships. Congratulations to all swimmers for their dedication and hard work in the pool, bringing honour to SLIIT.

Winning International Competitions

SLIIT students have participated in and excelled in various international competitions, including Robofest, Codefest, and the University of Queensland – Design Solution for Impact Competition, showcasing their skills and talent on a global stage.

Here’s a more detailed look at SLIIT’s involvement in international competitions:

Robofest:

SLIIT’s Faculty of Engineering organises the annual Robofest competition, which aims to empower students with skills in electronics, robotics, critical thinking, and problem-solving, preparing them to compete internationally and bring recognition to Sri Lankan talent.

Codefest:

CODEFEST is a nationwide Software Competition organized by the Faculty of Computing of Sri Lanka Institute of Information Technology (SLIIT) geared towards exhibiting the software application design and developing talents of students island-wide. It is an effort of SLIIT to elevate the entire nation’s ICT knowledge to achieve its aspiration of being the knowledge hub in Asia. CODEFEST was first organised in 2012 and this year it will be held for the 8th consecutive time in parallel with the 20th anniversary celebrations of SLIIT.

University of Queensland – Design Solution for Impact Competition:

SLIIT hosted the first-ever University of Queensland – Design Solution for Impact Competition in Sri Lanka, with 16 school teams from across the country participating.

International Open Day:

SLIIT organises an International Open Day where students can connect with distinguished lecturers and university representatives from prestigious institutions like the University of Queensland, Liverpool John Moores University, and Manchester Metropolitan University.

Brain Busters:

SLIIT Brain Busters is a quiz competition organised by SLIIT. The competition is open to students of National, Private and International Schools Island wide. The programme is broadcast on TV1 television as a series.

Inter-University Dance Competition:

SLIIT Team Diamonds for being selected as finalists and advancing to the Grand Finale of Tantalize 2024, the inter-university dance competition organised by APIIT Sri Lanka. The 14 talented team members from various SLIIT faculties have showcased their skills in Team Diamonds and earned their spot as finalists, competing among over 30 teams from state universities, private universities, and higher education institutes.

Softskills+

For the 11th consecutive year, Softskills+ returns with an exciting lineup of events aimed at honing essential soft skills among students. The program encompasses an interschool quiz contest and a comprehensive workshop focused on developing teamwork, problem-solving abilities, leadership qualities, and fostering creative thinking.

Recently, the Faculty of Business at SLIIT organised its annual Inter-school Quiz Competition and Soft Skills Workshop, marking its fifth successive year. Targeting students in grades 11 to 13 from Commerce streams across State, Private, and International schools, the workshop sought to ignite a passion for soft skills development, emphasising teamwork, problem-solving, creativity, and innovative thinking. Recognising the increasing importance of these soft skills in today’s workforce, the programme aims to fill the gap often left unaddressed in the school curriculum.”

The winners of the soft skill competition with Professor Lakshman Rathnayake: Chairman/Chancellor, Vice Chancellor/MD Professor Lalith Gamage, Professor Nimal Rajapakse: Senior Deputy Vice – Chancellor & Provost, Deputy Vice Chancellor – Research and International Affairs Professor Samantha Thelijjagoda, and Veteran Film Director Somarathna Dissanayake.

VogueFest 2024:

SLIIT Business School organised VogueFest 2024, a platform for emerging fashion designers under 30 to showcase their work and win prizes.

T-shirt Design Competition with Sheffield Hallam University:

SLIIT and Sheffield Hallam University (SHU) UK collaborated on a T-shirt designing competition, with a voting procedure to select the best design.

SLIIT’s Got Talent

: The annual talent show, SLIIT’s Got Talent 2024, was held for the 10th consecutive year at the Nelum Pokuna Mahinda Rajapaksa Theatre on 27th September 2024. SLIIT’s Got Talent had the audience energised with amazing performances, showcasing mind-blowing talent by the orchestra and the talented undergraduates from all faculties.

Other events:

* SLIIT also participates in events like the EDUVision Exhibition organised by the Richmond College Old Boys’ Association.

* They hosted the first-ever University of Queensland – Design Solution for Impact Competition in Sri Lanka.

* SLIIT Business School also organised the Business Proposal Competition.

SLIIT Academy:

SLIIT Academy (Pvt.) Ltd. provides industrial-oriented learning experiences for students.

International Partnerships:

SLIIT has strong international partnerships with universities like Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU), The University of Queensland (UQ), Manchester Metropolitan University (MMU), and Curtin University Australia, providing opportunities for students to study and participate in international events.

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT University, Malabe. He is also the author of the “Doing Social Research and Publishing Results”, a Springer publication (Singapore), and “Samaja Gaveshakaya (in Sinhala).

Features

Inescapable need to deal with the past

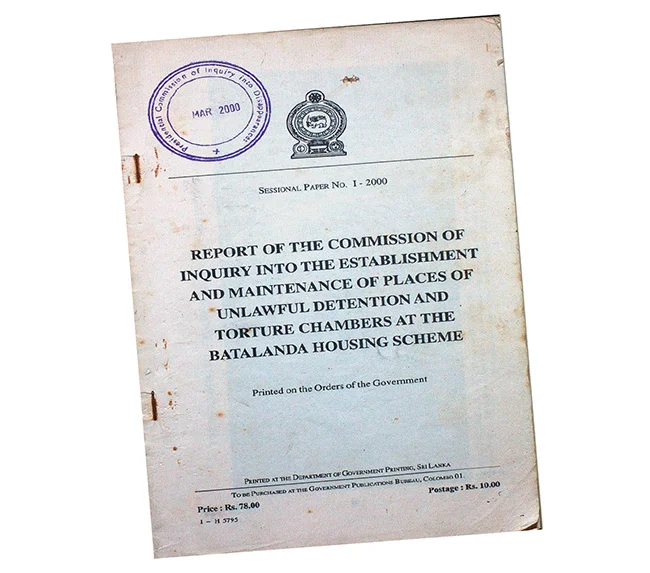

The sudden reemergence of two major incidents from the past, that had become peripheral to the concerns of people today, has jolted the national polity and come to its centre stage. These are the interview by former president Ranil Wickremesinghe with the Al Jazeera television station that elicited the Batalanda issue and now the sanctioning of three former military commanders of the Sri Lankan armed forces and an LTTE commander, who switched sides and joined the government. The key lesson that these two incidents give is that allegations of mass crimes, whether they arise nationally or internationally, have to be dealt with at some time or the other. If they are not, they continue to fester beneath the surface until they rise again in a most unexpected way and when they may be more difficult to deal with.

In the case of the Batalanda interrogation site, the sudden reemergence of issues that seemed buried in the past has given rise to conjecture. The Batalanda issue, which goes back 37 years, was never totally off the radar. But after the last of the commission reports of the JVP period had been published over two decades ago, this matter was no longer at the forefront of public consciousness. Most of those in the younger generations who were too young to know what happened at that time, or born afterwards, would scarcely have any idea of what happened at Batalanda. But once the issue of human rights violations surfaced on Al Jazeera television they have come to occupy centre stage. From the day the former president gave his fateful interview there are commentaries on it both in the mainstream media and on social media.

There seems to be a sustained effort to keep the issue alive. The issues of Batalanda provide good fodder to politicians who are campaigning for election at the forthcoming Local Government elections on May 6. It is notable that the publicity on what transpired at Batalanda provides a way in which the outcome of the forthcoming local government elections in the worst affected parts of the country may be swayed. The problem is that the main contesting political parties are liable to be accused of participation in the JVP insurrection or its suppression or both. This may account for the widening of the scope of the allegations to include other sites such as Matale.

POLITICAL IMPERATIVES

The emergence at this time of the human rights violations and war crimes that took place during the LTTE war have their own political reasons, though these are external. The pursuit of truth and accountability must be universal and free from political motivations. Justice cannot be applied selectively. While human rights violations and war crimes call for universal standards that are applicable to all including those being committed at this time in Gaza and Ukraine, political imperatives influence what is surfaced. The sanctioning of the four military commanders by the UK government has been justified by the UK government minister concerned as being the fulfilment of an election pledge that he had made to his constituents. It is notable that the countries at the forefront of justice for Sri Lanka have large Tamil Diasporas that act as vote banks. It usually takes long time to prosecute human rights violations internationally whether it be in South America or East Timor and diasporas have the staying power and resources to keep going on.

In its response to the sanctions placed on the military commanders, the government’s position is that such unilateral decisions by foreign government are not helpful and complicate the task of national reconciliation. It has faced criticism for its restrained response, with some expecting a more forceful rebuttal against the international community. However, the NPP government is not the first to have had to face such problems. The sanctioning of military commanders and even of former presidents has taken place during the periods of previous governments. One of the former commanders who has been sanctioned by the UK government at this time was also sanctioned by the US government in 2020. This was followed by the Canadian government which sanctioned two former presidents in 2023. Neither of the two governments in power at that time took visibly stronger stands.

In addition, resolutions on Sri Lanka have been a regular occurrence and have been passed over the Sri Lankan government’s opposition since 2012. Apart from the very first vote that took place in 2009 when the government promised to take necessary action to deal with the human rights violations of the past, and won that vote, the government has lost every succeeding vote with the margins of defeat becoming bigger and bigger. This process has now culminated in an evidence gathering unit being set up in Geneva to collect evidence of human rights violations in Sri Lanka that is on offer to international governments to use. This is not a safe situation for Sri Lankan leaders to be in as they can be taken before international courts in foreign countries. It is important for Sri Lanka’s sovereignty and dignity as a country that this trend comes to an end.

COMPREHENSIVE SOLUTION

A peaceful future for Sri Lanka requires a multi-dimensional approach that addresses the root causes of conflict while fostering reconciliation, justice, and inclusive development. So far the government’s response to the international pressures is to indicate that it will strengthen the internal mechanisms already in place like the Office on Missing Persons and in addition to set up a truth and reconciliation commission. The difficulty that the government will face is to obtain a national consensus behind this truth and reconciliation commission. Tamil parties and victims’ groups in particular have voiced scepticism about the value of this mechanism. They have seen commissions come and commissions go. Sinhalese nationalist parties are also highly critical of the need for such commissions. As the Nawaz Commission appointed to identify the recommendations of previous commissions observed, “Our island nation has had a surfeit of commissions. Many witnesses who testified before this commission narrated their disappointment of going before previous commissions and achieving nothing in return.”

Former minister Prof G L Peiris has written a detailed critique of the proposed truth and reconciliation law that the previous government prepared but did not present to parliament.

In his critique, Prof Peiris had drawn from the South African truth and reconciliation commission which is the best known and most thoroughly implemented one in the world. He points out that the South African commission had a mandate to cover the entire country and not only some parts of it like the Sri Lankan law proposes. The need for a Sri Lankan truth and reconciliation commission to cover the entire country and not only the north and east is clear in the reemergence of the Batalanda issue. Serious human rights violations have occurred in all parts of the country, and to those from all ethnic and religious communities, and not only in the north and east.

Dealing with the past can only be successful in the context of a “system change” in which there is mutual agreement about the future. The longer this is delayed, the more scepticism will grow among victims and the broader public about the government’s commitment to a solution. The important feature of the South African commission was that it was part of a larger political process aimed to build national consensus through a long and strenuous process of consultations. The ultimate goal of the South African reconciliation process was a comprehensive political settlement that included power-sharing between racial groups and accountability measures that facilitated healing for all sides. If Sri Lanka is to achieve genuine reconciliation, it is necessary to learn from these experiences and take decisive steps to address past injustices in a manner that fosters lasting national unity. A peaceful Sri Lanka is possible if the government, opposition and people commit to truth, justice and inclusivity.

by Jehan Perera

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoSri Lanka’s eternal search for the elusive all-rounder

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoGnanasara Thera urged to reveal masterminds behind Easter Sunday terror attacks

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoAIA Higher Education Scholarships Programme celebrating 30-year journey

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoBid to include genocide allegation against Sri Lanka in Canada’s school curriculum thwarted

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoComBank crowned Global Finance Best SME Bank in Sri Lanka for 3rd successive year

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoSanctions by The Unpunished

-

Latest News1 day ago

Latest News1 day agoIPL 2025: Rookies Ashwani and Rickelton lead Mumbai Indians to first win

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoMore parliamentary giants I was privileged to know