Midweek Review

Shakespeare in a takarang shed

by GEORGE BRAINE

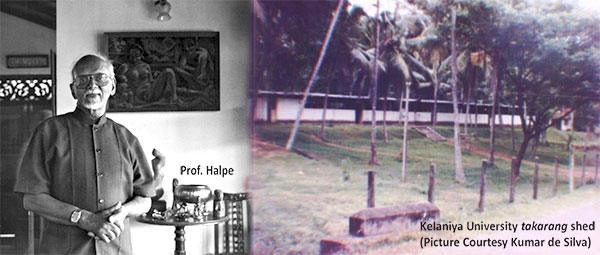

In a tribute to Prof. Ashley Halpe, his daughter recently wrote about the time he was “forced to give his lectures in a takarang shed”. That triggered my nostalgic memories, of sitting in those takarang sheds, both as a teacher and a student. This is that story.

But, let me begin at the beginning. In 1973, I was teaching English at a remote school in Uva, when the Vidyalankara campus advertised for English instructors. I was called for a written test, and, to my amazement, nearly 200 applicants had turned-up. I thought my chances were nil. Surprisingly, after a follow-up interview, I was selected – one of only three appointees.

Vidyalankara campus sat on a hill, at Kelaniya, not far from the Colombo – Kandy road. As one climbed the hill, back in the mid-1970s, the sports ground and the convocation hall would be on the left, followed by the science block and the library. On the right were the student centre and a dormitory for female students. Teachers travelled from home and students lived mostly in nearby boarding house. A no-frills, commuter campus.

After walking past these buildings, one descended the hill to a strange sight: a scattering of low slung takarang (zinc sheeted) buildings on either side of the road. On the left, one long structure housed the English department. On the right, a number of buildings housed the sub-department of English, offering general English courses to students of all majors. These courses were taught by a host of instructors, mainly English trained teachers like me. English majors, on the other hand, attended lectures conducted by professors, lecturers, and assistant lecturers.

The takarang sheds were spread among coconut palms, each consisting of a number of classrooms. The walls, which rose to about six feet, were made of cement blocks, crudely white-washed, topped by wire mesh. The roofs were zinc sheets, dented by falling coconuts and branches. The classrooms were hot, the teaching method was chalk-and-talk, and the students sat passively, bored, their minds elsewhere. On rainy days, the sound of rain on the roof was deafening, and all chairs were soon wet, not drying for days.

Vidyalankara, having been a pirivena (monastic college), enrolled a large number of young Buddhist monks. They were the better students, but, the longer they stayed at the university, the less inclined they were to remain in robes. Perhaps, the easy interaction with female students showed them the disadvantages of a celibate life.

After the 1971 insurrection, Vidyalankara had been a camp for captured “Che Guevarists”, and their kurutu gee (poetic graffiti) could still be seen in the basement of the science building. A few years later, a group of trainee math teachers were brutally ragged in that basement. Already, JVP led, Marxist-oriented student unions were making a comeback.

The senior common room, actually a partitioned off space on a staircase landing, is where all teachers, irrespective of rank, met and mixed. We chatted, read newspapers and magazines, had a cup of tea, and played carrom. One player I partnered was Lakdasa Wikkramasinha, having previously known him at Maharagama Teachers’ College. A man of few words, with a disdainful stare that made lesser mortals uncomfortable, he wore his shirt halfway buttoned that displayed his hairy chest, and the sleeves rolled up just below the elbow. He was already a well-known poet, and is now acknowledged as perhaps Sri Lanka’s best, writing in English.

A few years after joining, I was given permission to enroll full-time for a special degree in English at Vidyalankara itself. So I led a double life, an instructor and a student at the same time. As a student, I came into close contact with other students majoring in English, mainly young and female, as well as the teachers who taught them. My group of special degree students had five young females and me, the only male and a good 10 years older than my classmates. This was when English was cynically nicknamed kaduwa (sword). What I soon realized was that, despite their shabby appearance, the takarang sheds also sheltered inspiring and passionate teachers.

Prof. Doric de Souza was renowned among them. A Trotskyite politician and a Marxist theoretician, and a contemporary of NM Perera, Colvin R. de Silva, and Philip Gunawardena, Doric – tall, bald and slightly stooped – had a commanding personality. He had been a senator and a permanent secretary of a ministry, but dressed simply, in a bush shirt and cotton pants. He addressed students as Mr. or Miss. He never brought politics into the classroom.

Doric taught The Canterbury Tales, Chaucer’s 14th century classic. The tales were related by a motley collection of pilgrims, including a knight, a prioress, a monk, a man of law, a scholarly clerk, a miller, a wife of Bath and many others. Doric’s mode of teaching was to read the text in his sonorous voice, pausing to explain and ask for our questions and opinions.

Some tales contain explicit descriptions of debauchery. On the day the Miller’s Tale was to be discussed, the female classmates (young enough to be his grandchildren) waited, sitting upright with bated breath, staring at Doric mischievously, wondering how he would handle the bawdy parts. Doric was up to the mark, and, looking down on the text, read right through the lines, without a pause, explanation or question! The scene is etched in my mind.

Doric once invited me and two other instructors to the 80 Club for drinks, where the actor Gamini Fonseka stopped by our table to mention how much he admired Doric, whom he addressed as Sir. One instructor, a smart aleck, got into an argument with Gamini.

Those were the days of strict foreign exchange controls, and even essential textbooks for our courses were not freely available. The library was bereft of books, the shelves for English language and literature holding only a few tattered, outdated volumes. (Instead, the shelves were bulging with the thick volumes of the collected speeches of Kim Il-Sung, donated by the North Korean Embassy, and read by no one.) All this meant that we did not have secondary sources, or access to literary criticism. So, in tutorials, we wrote mainly what we had noted down in lectures. The lecturers would have found the endless repetition of their own ideas returning to them in student tutorials utterly boring.

AMG Sirimanne was perhaps the most popular and inspiring teacher. He did not have a commanding presence, nor did he stick to the text, interposing the lecture with anecdotes, usually funny. He taught Wordsworth with passion, taking us away from the mundane surroundings to a green and pleasant land, to a time of romance and places of natural beauty. He deftly added pithy statements in Sinhala to his lectures, and we barely noticed the intrusion. Sirimanne had a thriving tuition class for AL students, and that, in the eyes of his colleagues, somewhat lessened his standing as a scholar. But not in ours.

Teachers often adopt the teaching styles of their favourite teachers. In retrospect, I realize that Sirimanne was my model. I, too, would rarely stick to the textbook, mixing anecdotes and jokes as I taught.

Here’s a Sirimanne anecdote. When he was in the USA, studying on a scholarship, a parcel had arrived addressed to him. Sirimanne was summoned to the post office, and the parcel opened before him by a counter clerk. Upon seeing and smelling the contents, the clerk exclaimed “What’s this? Sh*t?” They were lumps of maldive fish.

Ranjith Gunewardena, fondly nicknamed “Ranjith Goonda” by the students, taught poetry in translation. His forte was the Spanish poet Anthonio Machado. In his rough smoker’s voice, Ranjith didn’t teach, but performed, his soaring voice and passion carrying him away. Himself a product of Vidyalankara, and equally fluent in Sinhala and English, he would shock his sheltered, privileged students with profanities. Behind that idiosyncratic, devil-may care personality, was a tender heart. He called me “machang” (we were similar in age). In fact, he had many “machangs”.

A few years ago, I sat next to a Spaniard on a flight. As we talked, I told him about the Machado poems I had read in the 70s, and still cherished. Then I recited the opening lines of “To José María Palacio”, Machado’s bitter sweet poem of nostalgia and longing, to the amazement of my fellow traveller. I remembered how avant garde Ranjith had been.

Palacio, my dear friend, is spring already covering the popular branchesby the river and the roads? On the plain of the upper Douro, spring comes late, but it’s so soft and lovely when it arrives! Do the old elms have some new leaves? Even though the acacias are still bareand the mountain tops clad in snow. Mount Moncayo up there, rosy and white, so beautiful against the sky of Aragon!

This was the time that the English department was moved from Peradeniya to Vidyalankara, for reasons too complex to describe here. That brought Prof. Ashley Halpe to us. We had not met him, but his reputation as a top Shakespearean scholar preceded his arrival.

He turned out to be a soft-spoken, low key, unassuming man. He traveled from Peradeniya to Kelaniya perhaps twice a week, taking the bus, so we had little opportunity to get to know him. Our loss. If he resented having to teach in a takarang shed, away from salubrious Peradeniya, he did not show it. Often dressed in a bush shirt, casual pants, and sandals, I can still picture him trudging up the hill.

He turned out to be a soft-spoken, low key, unassuming man. He traveled from Peradeniya to Kelaniya perhaps twice a week, taking the bus, so we had little opportunity to get to know him. Our loss. If he resented having to teach in a takarang shed, away from salubrious Peradeniya, he did not show it. Often dressed in a bush shirt, casual pants, and sandals, I can still picture him trudging up the hill.

Those were violent days on campuses. The JVP was in control of student councils, but UNP student unions were being formed, leading to inevitable clashes. Vidyalankara was a hotbed of these clashes, leading to frequent suspension of classes. (I stayed home so often that a neighbour asked me if I was unemployed.)

In 1977, the UNP came into power, and the campus clashes worsened. One day in March 1978, a bunch of thugs (organized by a prominent politician) swarmed up from Kandy road, armed with knives and iron rods, and attacked students at the student center. Outnumbered, the thugs were beaten-up and chased away by the students. An eerie, ominous silence descended. The road leading down to the Kandy road was deserted.

Lakdasa and I had watched this from the safety of the science block entrance, and noticed that someone was lying on the road, halfway between the student center and the Kandy road. We thought it was a student who had been ambushed.

So we walked down to the prone body and squatted down for a closer look. It was one of the thugs, badly beaten, his hair matted with blood, bleeding from the nostrils, taking horrific, long drawn breaths. He appeared to be breathing his last. Suddenly, we heard a wild yell and saw a number of thugs running up the hill, brandishing iron rods, already within a few yards of us. Lakdasa and I took to our heels, and ran uphill back for our dear lives. Had we been caught, we would have been severely beaten-up, if not killed. (The thug died the next day, and the President of the country attended his funeral.)

Lakdasa died a few months later, from drowning. He was only 36.

Those takarang sheds hid inspiring, charismatic teachers, with a wealth of talent. Some students, too, have gone to stellar careers, in Sri Lanka and abroad.

Vidyalankara became the University of Kelaniya in 1978. The takarang sheds survived that change.

Midweek Review

Rajiva on Batalanda controversy, govt.’s failure in Geneva and other matters

Former President Ranil Wickremesinghe’s recent interview with Mehdi Hasan on Al Jazeera’s ‘Head-to-Head’ series has caused controversy, both in and outside Parliament, over the role played by Wickremesinghe in the counter-insurgency campaign in the late’80s.

The National People’s Power (NPP) seeking to exploit the developing story to its advantage has ended up with egg on its face as the ruling party couldn’t disassociate from the violent past of the JVP. The debate on the damning Presidential Commission report on Batalanda, on April 10, will remind the country of the atrocities perpetrated not only by the UNP, but as well as by the JVP.

The Island sought the views of former outspoken parliamentarian and one-time head of the Government Secretariat for Coordinating the Peace Process (SCOPP) Prof. Rajiva Wijesinha on a range of issues, with the focus on Batalanda and the failure on the part of the war-winning country to counter unsubstantiated war crimes accusations.

Q:

The former President and UNP leader Ranil Wickremesinghe’s interview with Al Jazeera exposed the pathetic failure on the part of Sri Lanka to address war crimes accusations and accountability issues. In the face of aggressive interviewer Mehdi Hasan on ‘Head-to-Head,’ Wickremesinghe struggled pathetically to counter unsubstantiated accusations. Six-time Premier Wickremesinghe who also served as President (July 2022-Sept. 2024) seemed incapable of defending the war-winning armed forces. However, the situation wouldn’t have deteriorated to such an extent if President Mahinda Rajapaksa, who gave resolute political leadership during that war, ensured a proper defence of our armed forces in its aftermath as well-choreographed LTTE supporters were well in place, with Western backing, to distort and tarnish that victory completely. As wartime Secretary General of the Government’s Secretariat for Coordinating the Peace Process (since June 2007 till the successful conclusion of the war) and Secretary to the Ministry of Disaster Management and Human Rights (since Jun 2008) what do you think of Wickremesinghe’s performance?

A:

It made him look very foolish, but this is not surprising since he has no proper answers for most of the questions put to him. Least surprising was his performance with regard to the forces, since for years he was part of the assault forces on the successful Army, and expecting him to defend them is like asking a fox to stand guard on chickens.

Q:

In spite of trying to overwhelm Wickremesinghe before a definitely pro-LTTE audience at London’s Conway Hall, Hasan further exposed the hatchet job he was doing by never referring to the fact that the UNP leader, in his capacity as the Yahapalana Premier, co-sponsored the treacherous Geneva Resolution in Oc., 2015, against one’s own victorious armed forces. Hasan, Wickremesinghe and three panelists, namely Frances Harrison, former BBC-Sri Lanka correspondent, Director of International Truth and Justice Project and author of ‘Still Counting the Dead: Survivors of Sri Lanka’s Hidden War,’ Dr. Madura Rasaratnam, Executive Director of PEARL (People for Equality and Relief in Lanka) and former UK and EU MP and Wickremesinghe’s presidential envoy, Niranjan Joseph de Silva Deva Aditya, never even once referred to India’s accountability during the programme recorded in late February but released in March. As a UPFA MP (2010-2015) in addition to have served as Peace Secretariat Chief and Secretary to the Disaster Management and Human Rights Ministry, could we discuss the issues at hand leaving India out?

A:

I would not call the interview a hatchet job since Hasan was basically concerned about Wickremesinghe’s woeful record with regard to human rights. In raising his despicable conduct under Jayewardene, Hasan clearly saw continuity, and Wickremesinghe laid himself open to this in that he nailed his colours to the Rajapaksa mast in order to become President, thus making it impossible for him to revert to his previous stance. Sadly, given how incompetent both Wickremesinghe and Rajapaksa were about defending the forces, one cannot expect foreigners to distinguish between them.

Q:

You are one of the many UPFA MPs who backed Maithripala Sirisena’s candidature at the 2015 presidential election. The Sirisena-Wickremesinghe duo perpetrated the despicable act of backing the Geneva Resolution against our armed forces and they should be held responsible for that. Having thrown your weight behind the campaign to defeat Mahinda Rajapaksa’s bid to secure a third term, did you feel betrayed by the Geneva Resolution? And if so, what should have the Yahapalana administration done?

A:

By 2014, given the total failure of the Rajapaksas to deal firmly with critiques of our forces, resolutions against us had started and were getting stronger every year. Mahinda Rajapaksa laid us open by sacking Dayan Jayatilleke who had built up a large majority to support our victory against the Tigers, and appointed someone who intrigued with the Americans. He failed to fulfil his commitments with regard to reforms and reconciliation, and allowed for wholesale plundering, so that I have no regrets about working against him at the 2015 election. But I did not expect Wickremesinghe and his cohorts to plunder, too, and ignore the Sirisena manifesto, which is why I parted company with the Yahapalanaya administration, within a couple of months.

I had expected a Sirisena administration to pursue some of the policies associated with the SLFP, but he was a fool and his mentor Chandrika was concerned only with revenge on the Rajapaksas. You cannot talk about betrayal when there was no faith in the first place. But I also blame the Rajapaksas for messing up the August election by attacking Sirisena and driving him further into Ranil’s arms, so that he was a pawn in his hands.

Q:

Have you advised President Mahinda Rajapaksa’s government how to counter unsubstantiated war crimes allegations propagated by various interested parties, particularly the UN, on the basis of the Panel of Experts (PoE) report released in March 2011? Did the government accept your suggestions/recommendations?

A:

Prof. Rajiva Wijesinha

I kept trying, but Mahinda was not interested at all, and had no idea about how to conduct international relations. Sadly, his Foreign Minister was hanging around behind Namal, and proved incapable of independent thought, in his anxiety to gain further promotion. And given that I was about the only person the international community, that was not prejudiced, took seriously – I refer to the ICRC and the Japanese with whom I continued to work, and, indeed, the Americans, until the Ambassador was bullied by her doctrinaire political affairs officer into active undermining of the Rajapaksas – there was much jealousy, so I was shut out from any influence.

But even the admirable effort, headed by Godfrey Gunatilleke, was not properly used. Mahinda Rajapaksa seemed to me more concerned with providing joy rides for people rather than serious counter measures, and representation in Geneva turned into a joke, with him even undermining Tamara Kunanayagam, who, when he supported her, scored a significant victory against the Americans, in September 2011. The Ambassador, who had been intriguing with her predecessor, then told her they would get us in March, and with a little help from their friends here, they succeeded.

Q:

As the writer pointed out in his comment on Wickremesinghe’s controversial Al Jazeera interview, the former Commander-in-Chief failed to mention critically important matters that could have countered Hasan’ s line of questioning meant to humiliate Sri Lanka?

A:

How could you have expected that, since his primary concern has always been himself, not the country, let alone the armed forces?

Q:

Do you agree that Western powers and an influential section of the international media cannot stomach Sri Lanka’s triumph over separatist Tamil terrorism?

A:

There was opposition to our victory from the start, but this was strengthened by the failure to move on reconciliation, creating the impression that the victory against the Tigers was seen by the government as a victory against Tamils. The failure of the Foreign Ministry to work with journalists was lamentable, and the few exceptions – for instance the admirable Vadivel Krishnamoorthy in Chennai or Sashikala Premawardhane in Canberra – received no support at all from the Ministry establishment.

Q:

A couple of months after the 2019 presidential election, Gotabaya Rajapaksa declared his intention to withdraw from the Geneva process. On behalf of Sri Lanka that announcement was made in Geneva by the then Foreign Minister Dinesh Gunawardena, who became the Premier during Wickremesinghe’s tenure as the President. That declaration was meant to hoodwink the Sinhala community and didn’t alter the Geneva process and even today the project is continuing. As a person who had been closely involved in the overall government response to terrorism and related matters, how do you view the measures taken during Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s short presidency to counter Geneva?

A:

What measures? I am reminded of the idiocy of the responses to the Darusman report by Basil and Gotabaya Rajapaksa, who went on ego trips and produced unreadable volumes trying to get credit for themselves as to issues of little interest to the world. They were planned in response to Darusman, but when I told Gotabaya that his effort was just a narrative of action, he said that responding to Darusman was not his intention. When I said that was necessary, he told me he had asked Chief-of-Staff Roshan Goonetilleke to do that, but Roshan said he had not been asked and had not been given any resources.

My own two short booklets which took the Darusman allegations to pieces were completely ignored by the Foreign Ministry.

Q:

Against the backdrop of the Geneva betrayal in 2015 that involved the late Minister Mangala Samaraweera, how do you view President Wickremesinghe’s response to the Geneva threat?

A: Wickremesinghe did not see Geneva as a threat at all. Who exactly is to blame for the hardening of the resolution, after our Ambassador’s efforts to moderate it, will require a straightforward narrative from the Ambassador, Ravinatha Ariyasinha, who felt badly let down by his superiors. Geneva should not be seen as a threat, since as we have seen follow through is minimal, but we should rather see it as an opportunity to put our own house in order.

Q:

President Anura Kumara Dissanayake recently questioned both the loyalty and professionalism of our armed forces credited with defeating Northern and Southern terrorism. There hadn’t been a previous occasion, a President or a Premier, under any circumstances, questioned the armed forces’ loyalty or professionalism. We cannot also forget the fact that President Dissanayake is the leader of the once proscribed JVP responsible for death and destruction during 1971 and 1987-1990 terror campaigns. Let us know of your opinion on President Dissanayake’s contentious comments on the armed forces?

A: I do not see them as contentious, I think what is seen as generalizations was critiques of elements in the forces. There have been problems, as we saw from the very different approach of Sarath Fonseka and Daya Ratnayake, with regard to civilian casualties, the latter having planned a campaign in the East which led to hardly any civilian deaths. But having monitored every day, while I headed the Peace Secretariat, all allegations, and obtained explanations of what happened from the forces, I could have proved that they were more disciplined than other forces in similar circumstances.

The violence of the JVP and the LTTE and other such groups was met with violence, but the forces observed some rules which I believe the police, much more ruthlessly politicized by Jayewardene, failed to do. The difference in behaviour between the squads led for instance by Gamini Hettiarachchi and Ronnie Goonesinghe makes this clear.

Q:

Mehdi Hasan also strenuously questioned Wickremesinghe on his role in the UNP’s counter-terror campaign during the 1987-1990 period. The British-American journalists of Indian origins attacked Wickremesinghe over the Batalanda Commission report that had dealt with extra-judicial operations carried out by police, acting on the political leadership given by Wickremesinghe. What is your position?

A:

Wickremesinghe’s use of thugs’ right through his political career is well known. I still recall my disappointment, having thought better of him, when a senior member of the UNP, who disapproved thoroughly of what Jayewardene had done to his party, told me that Wickremesinghe was not honest because he used thugs. In ‘My Fair Lady,’ the heroine talks about someone to whom gin was mother’s milk, and for Wickremesinghe violence is mother’s milk, as can be seen by the horrors he associated with.

The latest revelations about Deshabandu Tennakoon, whom he appointed IGP despite his record, makes clear his approval for extra-judicial operations.

Q:

Finally, will you explain how to counter war crimes accusations as well as allegations with regard to the counter-terror campaign in the’80s?

A:

I do not think it is possible to counter allegations about the counter-terror campaign of the eighties, since many of those allegations, starting with the Welikada Prison massacre, which Wickremesinghe’s father admitted to me the government had engendered, are quite accurate. And I should stress that the worst excesses, such as the torture and murder of Wijeyedasa Liyanaarachchi, happened under Jayewardene, since there is a tendency amongst the elite to blame Premadasa. He, to give him his due, was genuine about a ceasefire, which the JVP ignored, foolishly in my view though they may have had doubts about Ranjan Wijeratne’s bona fides.

With regard to war crimes accusations, I have shown how, in my ‘Hard Talk’ interview, which you failed to mention in describing Wickeremesinghe’s failure to respond coherently to Hasan. The speeches Dayan Jayatilleke and I made in Geneva make clear what needed and still needs to be done, but clear sighted arguments based on a moral perspective that is more focused than the meanderings, and the frequent hypocrisy, of critics will not now be easy for the country to furnish.

By Shamindra Ferdinando

Midweek Review

Research: Understanding the basics and getting started – Part I

Introduction

No human civilization—whether large or small, modern or traditional—has ever survived without collectively engaging in three fundamental processes: the production and distribution of goods and services, the generation and dissemination of knowledge and culture, and the reproduction and sustenance of human life. These interconnected functions form the backbone of collective existence, ensuring material survival, intellectual continuity, and biological renewal. While the ways in which these functions are organised vary according to technological conditions, politico-economic structures and geo-climatic contexts, their indispensability remains unchanged. In the modern era, research has become the institutionalized authority in knowledge production. It serves as the primary mechanism through which knowledge is generated, rooted in systematic inquiry, methodological rigor, and empirical validation. This article examines the key aspects of knowledge formation through research, highlighting its epistemological foundations and the systematic steps involved.

What is knowledge?

Knowledge, at its core, emerged from humanity’s attempt to understand itself and its surroundings. The word “knowledge” is a noun derived from the verb “knows.” When we seek to know something, the result is knowledge—an ongoing, continuous process. However, those who seek to monopolise knowledge as a tool of authority often attribute exclusivity or even divinity to it. When the process of knowing becomes entangled with power structures and political authority, the construction of knowledge risks distortion. It is a different story.

Why do we seek to understand human beings and our environment? At its core, this pursuit arises from the reality that everything is in a state of change. People observe change in their surroundings, in society, and within themselves. Yet, the reasons behind these transformations are not always clear. Modern science explains change through the concept of motion, governed by specific laws, while Buddhism conceptualises it as impermanence (Anicca)—a fundamental characteristic of existence. Thus, knowledge evolves from humanity’s pursuit to understand the many dimensions of change

It is observed that Change is neither random nor entirely haphazard; it follows an underlying rhythm and order over time. Just as nature’s cycles, social evolution, and personal growth unfold in patterns, they can be observed and understood. Through inquiry and observation, humans can recognise these rhythms, allowing them to adapt, innovate, and find meaning in an ever-changing world. By exploring change—both scientifically and philosophically—we not only expand our knowledge but also cultivate the wisdom to navigate life with awareness and purpose.

How is Knowledge Created?

The creation of knowledge has long been regarded as a structured and methodical process, deeply rooted in philosophical traditions and intellectual inquiry. From ancient civilizations to modern epistemology, knowledge generation has evolved through systematic approaches, critical analysis, and logical reasoning.

All early civilizations, including the Chinese, Arab, and Greek traditions, placed significant emphasis on logic and structured methodologies for acquiring and expanding knowledge. Each of these civilizations contributed unique perspectives and techniques that have shaped contemporary understanding. Chinese tradition emphasised balance, harmony, and dialectical reasoning, particularly through Confucian and Taoist frameworks of knowledge formation. The Arab tradition, rooted in empirical observation and logical deduction, played a pivotal role in shaping scientific methods during the Islamic Golden Age. Meanwhile, the Greek tradition advanced structured reasoning through Socratic dialogue, Aristotelian logic, and Platonic idealism, forming the foundation of Western epistemology.

Ancient Indian philosophical traditions employed four primary strategies for the systematic creation of knowledge: Contemplation (Deep reflection and meditation to attain insights and wisdom); Retrospection (Examination of past experiences, historical events, and prior knowledge to derive lessons and patterns); Debate (Intellectual discourse and dialectical reasoning to test and refine ideas) and; Logical Reasoning (Systematic analysis and structured argumentation to establish coherence and validity).The pursuit of knowledge has always been a dynamic and evolving process. The philosophical traditions of ancient civilizations demonstrate that knowledge is not merely acquired but constructed.

Research and Knowledge

In the modern era, research gradually became the dominant mode of knowledge acquisition, shaping intellectual discourse and scientific progress. The structured framework of rules, methods, and approaches governing research ensures reliability, validity, and objectivity. This methodological rigor evolved alongside modern science, which institutionalized research as the primary mechanism for generating new knowledge.

The rise of modern science established the authority and legitimacy of research by emphasizing empirical evidence, systematic inquiry, and critical analysis. The scientific revolution and subsequent advancements across various disciplines reinforced the notion that knowledge must be verifiable and reproducible. As a result, research became not just a tool for discovery, but also a benchmark for evaluating truth claims across diverse fields. Today, research remains the cornerstone of intellectual progress, continually expanding human understanding and serving as a primary tool for the formation of new knowledge.

Research is a systematic inquiry aimed at acquiring new knowledge or enhancing existing knowledge. It involves specific methodologies tailored to the discipline and context, as there is no single approach applicable across all fields. Research is not limited to academia—everyday life often involves informal research as individuals seek to solve problems or make informed decisions.It’s important to distinguish between two related but distinct activities: search and research. Both involve seeking information, but a search is about retrieving a known answer, while research is the process of exploring a problem without predefined answers. Research aims to expand knowledge and generate new insights, whereas search simply locates existing information.

Western Genealogy

The evolution of Modern Science, as we understand it today, and the establishment of the Scientific Research Method as the primary mode of knowledge construction, is deeply rooted in historical transformations across multiple spheres in Europe.

A critical historical catalyst for the emergence of modern science and scientific research methods was the decline of the medieval political order and the rise of modern nation-states in Europe. The new political entities not only redefined governance but also fostered environments where scientific inquiry could thrive, liberated from the previously dominant influence of religious institutions. Establishment of new universities and allocation of funding for scientific research by ‘new monarchs’ should be noted. These shifting power dynamics created space for scientific research more systematically. The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge was founded in 1662, while the French Academy of Sciences (Académie des Sciences) was established in 1666 under royal patronage to promote scientific research.

Alongside this political evolution, the feudal economic order declined, paving the way for modern capitalism. This transformation progressed through distinct stages, from early commercial capitalism to industrial capitalism. The rise of commercial capitalism created a new economic foundation that supported the funding and patronage of scientific research. With the advent of industrial capitalism, the expansion of factories, technological advancements, and the emphasis on mass production further accelerated innovation in scientific methods and applications, particularly in physics, engineering, and chemistry.

For centuries, the Catholic Church was the dominant ideological force in Europe, but its hegemony gradually declined. The Renaissance played a crucial role in challenging the Church’s authority over knowledge. This intellectual revival, along with the religious Reformation, fostered an environment conducive to alternative modes of thought. Scholars increasingly emphasised direct observation, experimentation, and logical reasoning—principles that became the foundation of modern science.

Research from Natural Science to Social Science

During this period, a new generation of scientists emerged, paving the way for groundbreaking discoveries that reshaped humanity’s understanding of the natural world. Among them, Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543), Johannes Kepler (1571–1630), Galileo Galilei (1564–1642), and Isaac Newton (1642–1726) made remarkable contributions, expanding the boundaries of human knowledge to an unprecedented level.

Like early scientists who sought to apply systematic methods to the natural world, several scholars aimed to bring similar principles of scientific inquiry to the study of human society and behavior. Among them, Francis Bacon (1561–1626) championed the empirical method, emphasising observation and inductive reasoning as the basis for knowledge. René Descartes (1596–1650) introduced a rationalist approach, advocating systematic doubt and logical deduction to establish fundamental truths. David Hume (1711–1776) further advanced the study of human nature by emphasizing empirical skepticism, arguing that knowledge should be derived from experience and sensory perception rather than pure reason alone.

Fundamentals of Modern Scientific Approach

The foundation of modern scientific research lies in the intricate relationship between perception, cognition, and structured reasoning.

Sensation, derived from our senses, serves as the primary gateway to understanding the world. It is through sensory experience that we acquire raw data, forming the fundamental basis of knowledge.

Cognition, in its essence, is a structured reflection of these sensory inputs. It does not exist in isolation but emerges as an organised interpretation of stimuli processed by the mind. The transition from mere sensory perception to structured thought is facilitated by the formation of concepts—complex cognitive structures that synthesize and categorize sensory experiences.

Concepts, once established, serve as the building blocks of higher-order thinking. They enable the formulation of judgments—assessments that compare, contrast, or evaluate information. These judgments, in turn, contribute to the development of conclusions, allowing for deeper reasoning and critical analysis.

A coherent set of judgments forms more sophisticated modes of thought, leading to structured arguments, hypotheses, and theoretical models. This continuous process of refining thought through judgment and reasoning is the driving force behind scientific inquiry, where knowledge is not only acquired but also systematically validated and expanded.

Modern scientific research, therefore, is a structured exploration of reality, rooted in sensory perception, refined through conceptualisation, and advanced through logical reasoning. This cyclical process ensures that scientific knowledge remains dynamic, evolving with each new discovery and theoretical advancement.

( Gamini Keerawella taught Historical Method, and Historiography at the University of Peradeniya, where he served as Head of the Department and Senior Professor of History. He is currently a Professor Emeritus at the same university)

by Gamini Keerawella

Midweek Review

Guardians of the Sanctuary

The glowing, tranquil oceans of green,

That deliver the legendary cup that cheers,

Running to the distant, silent mountains,

Are surely a sanctuary for the restive spirit,

But there’s pained labour in every leaf,

That until late was not bestowed the ballot,

But which kept the Isle’s economy intact,

And those of conscience are bound to hope,

That the small people in the success story,

Wouldn’t be ignored by those big folk,

Helming the struggling land’s marketing frenzy.

By Lynn Ockersz

-

Foreign News4 days ago

Foreign News4 days agoSearch continues in Dominican Republic for missing student Sudiksha Konanki

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoRichard de Zoysa at 67

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoThe Royal-Thomian and its Timeless Charm

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoDPMC unveils brand-new Bajaj three-wheeler

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days ago‘Thomia’: Richard Simon’s Masterpiece

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoSri Lanka to compete against USA, Jamaica in relay finals

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoSL Navy helping save kidneys

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoWomen’s struggles and men’s unions