Features

A senior cop remembers April 1971

(Excerpted from the memoirs of Senior DIG (Retd.) Edward Gunawardena)

A few months after the SLFP-led United Front Alliance headed by Mrs. Sirima Bandaranaike was elected in 1970, information started trickling in that the JVP was planning an uprising against the government. Cells were formed island-wide and clandestine indoctrination classes conducted by trained cadres. Simultaneously there was a spate of bank robberies and thefts of guns from households were reported to the police from all parts of the island. Unidentified youths were collecting empty cigarette and condensed milk tins, bottles, spent bulbs and cutting pieces of barbed wire from fences to make hand bombs and Molotov cocktails. Instances of bombs being tested even in the Peradeniya campus came to light.

By January 1971 the threat became real and the police began making arrests. Rohana Wijeweera, the leader of the movement, was arrested with an accomplice Kelly Senanayake at Amparai and detained at the Magazine prison. In the villages the common talk was that a ‘Che Guevera’ movement has started. Unknown youth moving about in villages were being referred to as ‘Che Gueveras.’ Police intelligence briefed the government of the developing ‘Naxalite’ like situation and action was taken to alert all police stations.

At the end of March 1971 there was specific information that the first targets would be the police stations. The attacks were to be carried out simultaneously on a particular day at a given time. With heightened police activity, the JVP ‘attack groups’ were pressurized to put their plan into effect hurriedly despite Wijeweera being incarcerated.

Synchronizing the attacks was a problem for the JVP. Mobile phones were not available then and the leaders had to resort to coded messages in newspapers. Police intelligence was able to crack their codes without much difficulty. It came to light that all police stations would come under attack at midnight on of April 5. The plan was to fire with guns at the station, and throw hand bombs and Molotov cocktails so that the policemen would run away or be killed. The attackers were to rush in and seize all the firearms in the stations.

The Police were ordered to be on full alert on this day. On April 4, in addition to my duties as the Director, Police Planning and Research I was acting for Mr. P. L. Munidasa, SP as the Personal Assistant to Mr.Stanley Senanayake the IGP. At about 4 p.m. an urgent radio message addressed to the IGP was opened by me. The message was alarming. The Wellawaya Police station had been attacked and the OIC Inspector Jayasekera had received gunshot injuries, a PC killed and several injured. The police had fought back bravely and not abandoned the station.

The Police were ordered to be on full alert on this day. On April 4, in addition to my duties as the Director, Police Planning and Research I was acting for Mr. P. L. Munidasa, SP as the Personal Assistant to Mr.Stanley Senanayake the IGP. At about 4 p.m. an urgent radio message addressed to the IGP was opened by me. The message was alarming. The Wellawaya Police station had been attacked and the OIC Inspector Jayasekera had received gunshot injuries, a PC killed and several injured. The police had fought back bravely and not abandoned the station.

As soon as the IGP was informed, he reacted calmly. He summoned all the senior officers present at Headquarters briefed them and ordered that all police stations including the Field Force Headquarters, the Training School and Police Headquarters itself be placed on full alert with immediate effect. Among the officers present I distinctly remember DIGs S.S. Joseph and T.B. Werapitiya. All police officers irrespective of rank were to be armed and issued with adequate ammunition. This task was entrusted to ASP M.D. Perera of Field Force Headquarters who was in charge of the armoury. I too was issued with a Sterling Sub-machine gun.

During this time I was living in Battaramulla with my wife and year old child in my father’s house. My brothers, Owen and Aelian, who were unmarried were also living there. My wife and I with the child occupied a fairly large room in which an official telephone had been installed. We had decided to live here as I had started building a house on the same ancestral property; and it is in this house that we have lived since 1971. 1 had an official car, a new Austin A40 which I drove as I had not been able to find a suitable police driver. Apart from the telephone, I had a walkie-talkie and was in constant communication with the Police Command Room and the IGP.

On the night of April 4 as there was nothing significant happening except for radio messages from police stations asking for additional strength, weapons and ammunition, I was permitted by the IGP to get back home. I telephoned the Welikada and Talangama police stations and was informed that the stations were being guarded and the areas were quiet. At about 10 p.m. I reached home safely and slept soundly. But something strange happened which to date remains a mystery. At about 3.30 a.m. (on the April 5) my telephone rang. The caller in a very authoritative voice said, “This is Capt. Gajanayake from Temple Trees, the Prime Minister wants you immediately.”

I hurriedly got into my uniform and woke up my wife and told her about the call. Just then it occurred to me that I should call Temple Trees. There was an operations room already functioning there and Mr. Felix Dias Bandaranaike had taken control of the situation. When I called, it was answered by my friend and colleague Mr. Cyril Herath. He assured me that I was not required at Temple Trees and that there was no person there by the name of Capt. Gajanayake. Much against the wishes of my wife, my father and brothers, dressed in a sarong and shirt and armed with my revolver I walked down the road for about half a kilometer. But there was none on the road at that time of the night.

By next night disturbing messages were coming to Police Headquarters from all over the Island. A large number of police stations had been attacked and police officers killed and injured. SP Navaratnam and Inspector Thomasz had been shot at on the road in Elpitiya and the latter had succumbed to the injuries. A number of Estate Superintendents had been shot dead. Trees were cut and electricity posts brought down. Desperate messages were pouring in from several Districts stating that administration had come to a standstill. The Kegalle, Kurunegala, Galle and Anuradhapura Districts were the worst affected. The least damage was in areas where the police had taken the offensive. In Colombo although the police stations were not attacked there was panic. With the possibility of water mains being damaged tube wells were hurriedly sunk at Temple Trees. General Attygalle, the Army Commander, had taken over the security of the Prime Minister and Temple Trees.

Talangama Police station that policed Battaramulla was guarded by the people of the area. Even my brothers spent the nights there armed with my father’s shotgun. IP Terrence Perera who was shot dead by the JVP in 1987 was the OIC. The excellent reputation he had in the area made ordinary folk flock to the station and take up positions to defend it if it was attacked. Some of the people of Battaramulla who were regularly there whose names I can remember and who are still living are K.C. Perera, W.A.C. Perera, Jayasiri, Victor Henry, Lionel Caldera and P.P. de Silva among others. Incidentally Brigadier Prasanna de Silva one of the heroes of the recently concluded war against the LTTE is a son of P.P. de Silva.

There were also those who gave assistance in the form of food and drink for all those who had gone to the aid of the police. The late Edward Rupasinghe a prominent businessman of Battaramulla, supplied large quantities of bread and short eats from the Westown Bakery which he owned. However as the attacks on police stations and state property became more and more intense, the SP Nugegoda T.S. Bongso decided to close down the Talangama Police Station and withdraw all the officers to the Mirihana Headquarters Station. This move made it unsafe for me to live in Battaramulla and travel to Police Headquarters.

The late Mr. Tiny Seneviratne SP and his charming wife readily accommodated us in their official quarters at Keppetipola Mawatha. The late Mr. K.B. Ratnayake had also left his Anuradhapura residence to live with the Seneviratnes. KBR and Tiny were good friends. During this time in the midst of all the disheartening news from all directions there were a few bright spots I have not forgotten. These were messages from Amparai, Kurunegala and Mawanella.

At Amparai the ASP in charge A.S. Seneviratne on information received that a busload of armed insurgents were on the way to attack the police station in broad daylight had hurriedly evacuated the station and got men with arms to hide behind trees and bushes having placed a few dummy policemen near the reserve table that was visible as one entered the station. As the busload of insurgents turned into the police station premises a hail of gunfire had been directed at it. About 20 insurgents had been killed and the bus set ablaze.

In Kurunegala the Pothuhera police station had been overrun and occupied by insurgents. Mr. Leo Perera who was ASP Kurunegala had approached the station with a party in mufti unnoticed by the insurgents, taken them by surprise and shot six of them dead. The police station had been reestablished immediately after.

In Mawanella and Aranayake the insurgents held complete sway. Two youths had visited the house of a retired school master on the outskirts of Mawanella town and demanded his gun. He had gone in, and loaded his double barrel gun and come out on the pretext of handing it over to the two youths he had shot them both dead discharging both barrels. The schoolmaster and his family had taken their belongings, got into a lorry and immediately left the area.

With the joint operations Room at Temple Trees under Minister Felix Dias Bandaranaike assisted by the Service Chiefs, the IGP and several senior public servants functioning fully the offensive against the insurgents began to work successfully. Units from the Army, Navy and the Air Force were actively assisting the police in all parts of the Island particularly in making arrests. Helicopters with pilots provided by India and Pakistan were being extensively used by officials and senior officers of the Armed Services and the Police for urgent travel.

On the night of April 10 or 11, I had finished my work at Police Headquarters and returned at about 10 p.m. to Keppetipola Mawatha. During the day my wife had been able to find a police jeep to be sent to Battaramulla to fetch a substantial supply of jak fruits, manioc and coconuts from our garden. The Seneviratnes took immense pleasure in feeding all and sundry who visited their home.

At about 10 p.m. I received a call from the IGP requesting me to take over Kurunegala Division the following morning. He told me that a helicopter would be ready for me at Parsons Road Air Force Grounds at 5.30 a.m. According to him the insurgents were still active in the area; the SP Mr. A. Mahendran was on sick leave and Mr. Leo Perera ASP was bravely handling the situation almost single handed. Although the assignment did not bother me much, my wife was noticeably concerned. Mrs. Seneviratne an ardent Catholic gave me a miniature medal of St. Anthony assuring me that the Saint will protect me from harm.

The helicopter took off at the crack of dawn. It was piloted by a young Flt.. Lieutenant from the SLAF and I was the only passenger. I have forgotten the name of this pilot. He was a pleasant guy who kept conversing with me all the way. He told me that he had flown to Anuradhapura and Deniyaya the previous day and in both those areas the insurgents were on the run and the security forces were on top.

Having been cloistered at Police Headquarters always peeking out of windows with a weapon in the ready or reading messages of deaths of police officers and the successes of insurgents, a feeling of relief overtook me on the flight. In fact I began to look forward to some action and this did not take long to come.

As the helicopter landed I was met by ASP Leo Perera who was a contemporary of mine at Peradeniya. There were several other police officers and also two officers of the Air Force. The latter were there to go to Colombo in the same aircraft. I carried only a travel bag with the minimum of clothes.

My first task was to address the officers gathered at the Police Station. I praised them for facing the situation bravely. Their only complaint was that they were short of ammunition. I suggested to Leo that as far as possible shotguns be used instead of 303 rifles. An officer was dispatched immediately to get as many guns as possible from the Kachcheri and the production room of the court house.

ASP M.D. Perera of Field Force Headquarters who was contacted on radio undertook to airlift 15 boxes of SG and No. four 12-bore cartridges. All the officers present were pleased as they all agreed that shotguns were more effective. The families of police officers too had left their quarters and barracks and taken up residence in different sections of the station. Most importantly their morale was high. Leo Perera had led them admirably.

At about 10 a.m. after partaking of a kiribath and lunumiris breakfast with the men I left for my office, that of the SP Kurunegala. I was very happy when Inspector Subramaniam was assigned to me. He was known to me and he appeared to be pleased with the task. He was a loyal and cheerful type. I chose a Land Rover with a removable canvas top for my use and also a sergeant and two constables with rifles. Subramaniam and I had Sterling sub-machine guns. These officers were to be with me at all times. In the afternoon I was able to obtain two double barrel Webley & Scott shotguns with about 10 No. four cartridges. There were several beds also already in place in the office. Telephoning my wife was no problem as I enjoyed the privilege of priority calls.

I had lunch with Inspector Subramaniam and my escort in the office. The rice and curry lunch had been sent from the Police Station mess. After a late lunch and a brief post lunch rest the four of us dressed in mufti set off in the Land Rover driven by a police driver. IP Subramaniam carried a Stirling sub-machine gun and the sergeant and PC 303 rifles. A loaded double barrel gun lay on the floor board of the Land Rover. After visiting the Potuhera and Mawathagama stations and patrolling the town area we returned to our base. Subramaniam also made arrangements with a boutique in town for some egg hoppers to be delivered to us at 8 p.m.

A little excitement was to come soon. After refreshing ourselves and having eaten the egg hoppers we visited the station. At about 9.45 p.m. I was having a discussion with a few officers in the office of the OIC Crimes when we heard two minor explosions and somebody screaming that the station was being attacked. Armed officers took up positions according to instructions. I ordered that the station lights be put off. An Inspector armed with a loaded shotgun, a few constables and I crawled to the rear of the building. Bombs were being thrown from the direction of a clump of plantain trees. A small tin with the fuse still burning fell close to where we were.

A PC jumped forward and doused the fuse throwing a wet gunny bag on the object. Two more similar objects fell thrown from the same direction. The same PC rushed forward and removed the burning fuses with his hands. As the objects were coming from about the identical place, I grabbed the shotgun and discharged both barrels in that direction simultaneously. The ‘bombing’ stopped thereafter. Two armed mobile patrols were sent out to the roads to look for any suspects. But the roads were empty. At about 11 p.m. the lights were put on and the station resumed its activities.

To say the least these ‘bombs’ were crude and primitive. In each of these we found a large ‘batta’ cracker the fuse of which came out of a hole in the lid of a cigarette tin. Round the ‘batta’ was a layer of tightly compressed fibres akin to the fibres in a squirrels nest. On the outer side of the compressed fibre were barbs cut off barbed wire and rusted nails. A thousand of such ‘bombs’ could not have matched the destructive force of a modern hand grenade. This state of unpreparedness was perhaps the foremost reason why the insurrection fizzled out early.

More action was to follow that same night. After my escort of three officers and I had retired to bed in the SP’s office, a few minutes after midnight the Sergeant guarding a large transformer on the Wariyapola Road with two other constables started calling me on the walkie talkie in a desperate tone. He sounded very excited and told me that shots were being heard close to the guard point. I instructed him to take up position a reasonable distance away from the transformer where there were no lights and shoot at sight any person or persons approaching the transformer. I also assured him that I would be at the guard post with an armed party in the quickest possible time.

IP Subramaniam and the other two officers were eager to join me. I got the driver to remove the hood cloth of the Land Rover. Whilst the sergeant who was armed with a rifle occupied the front seat alongside the driver, Subramaniam and I armed with two double barrel guns loaded with No. four cartridges took up a standing position with the guns resting on the first bar of the hood. The two PCs were to observe either side of the road. Prior to leaving I radioed the Police station to inform the Airforce operations room about my movements and not to have any foot patrols in the vicinity of the transformer.

There were no vehicles or any pedestrians on the way to the transformer. About a hundred meters to go we noticed a group of about eight to 10 dressed in shorts getting on to the road from the shrub. The distance was about 50 to 75 meters. The driver instinctively slowed down. The shining butts of two to three guns made us react instantly. I whispered to Subramaniam when I say ‘Fire’ to pull both triggers one after the other. We fired simultaneously and the Sergeant and PCs also fired their rifles.

Once the smoke cleared we noticed that the group had vanished.

As we approached the spot with the headlights on we noticed three shot guns scattered about the place. On closer examination there was blood all over and a man lay fallen groaning in pain. Beside him was a cloth bag which contained six cigarette tin hand bombs. Two live cartridges were also found. In two of the guns the spent cartridges were stuck as the ejectors were not working. The other gun was loaded with a ball cartridge which had not been fired. Having collected the guns, the bag containing the bombs and some rubber slippers that had been left behind. We proceeded on our mission to the transformer having radioed the guard Sergeant that we were close by.

As we approached the transformer the Guard Sergeant and the 2 PCs came out of the darkness to greet us. They were visibly relieved. But when the Sergeant told us that several shots were heard even 15 minutes before we arrived, I explained to them what had happened on the way. The Sergeant’s immediate response was, “They must be the rascals who were hovering about the village. They are some rowdies from outside this area who are pretending to be Che Guevaras”.

After reassuring them we left. On the way we stopped at the place where the shooting occurred. The man who was on the ground groaning in pain was not there.

Having snatched a couple of hours of sleep, at about 9 a.m. I drove with the escort to the Kurunegala Convent to call on the Co-ordinating officer Wing Commander Weeratne. A charming man, he received me cordially. He looked completely relaxed, dressed only in a shirt and sarong. He introduced me to several other senior officers of the Airforce and Army who were billeted in that spacious rectangular hall. One of the officers to whom I was introduced was Major Tony Gabriel the eminent cancer surgeon. A volunteer, he had been mobilized. I was also told that a bed was reserved for me. But I politely told him that I preferred to operate from my office. Wing Commander Weeratne also told me that he would be leaving to Colombo on the following day and the arrangement approved by Temple Trees was for the SP to act whenever the Co-ordinating officer was out of Kurunegala.

I joined the Co-ordinating officer and others at breakfast – string hoppers, kirihodi and pol sambol and left for the Police Station soon after. The escort was also well looked after. Weeratne and Tony Gabriel became good friends of mine. Sadly they are both not among the living today. After the meeting with the Co-ordinating officer we visited the Potuhera Police Station. Blood stains were clearly visible still and the walls and furniture were riddled with bullet and pellet marks. The officers looked cheerful and well settled. They were all full of praise for the exemplary courage shown by ASP Leo Perera in destroying the insurgents and other riffraff who were occupying the station and for re-establishing it quickly. One officer even went to the extent of suggesting that a brass plaque be installed mentioning the feat of Mr. Leo Perera.

When we returned to Kurunegala the officers were having lunch at the Station. The time was about 1.30 p.m. We too joined. Leo Perera was also there. He had tried several times to look me up but had failed. I complimented him for the excellent work done and told him that the high morale of the Kurunegala police was solely due to his leadership. He smiled in acknowledgment. But I noticed that he was not all that happy. He had a worried look on his face.

At about this time a serious incident had taken place giving the indication that insurgents were still active in the area. An Aiforce platoon (flight) on a recce in the outskirts of the town had come across a group of insurgents in a wooded area. The surprised group had surrendered with a few shot guns. An airman noticing one stray insurgent who was taking cover behind a bush had challenged him to surrender. The insurgent had instantly fired a shot at the airman who had dropped dead. The attacker had been shot dead in return by another airman.

At about 3 p.m. an Airforce vehicle drew up at the police station with a load of nine young men who had been arrested. They had deposited the two dead bodies at the hospital mortuary. All those under arrest were boys in their teens dressed in blue shorts and shirts. They had all been badly beaten up. I cautioned the airmen not to beat them further and took them into police custody. They had bleeding wounds which were washed and attended to by several policemen as they were all innocent looking children.

On questioning they confessed that they were retreating from the Warakapola area and their destination was the Ritigala jungles in Anuradhapura. They had these instructions from their high command. At this time, as if from nowhere appeared two young foreign journalists, a man and a woman. One was from the Washington Post and the other, the young woman from the Christian Science Monitor. Apart from taking photographs they too asked various questions.

The boys had their mouths and teeth were badly stained. They had been chewing tender leaves to get over their hunger. According to them they had been taught various ways to survive in the jungle. They had been told to eat apart from fruits and berries and tender leaves even creatures such as lizards and snakes; and insects particularly termites and earthworms. The nine young men were provided bathing facilities and a meal of buns and plantains; and locked up with about five more insurgent suspects to be sent to the rehabilitation camp that had been established at the Sri Jayawardenapura University premises. This was to be done on the following day in a hired van under a police escort.

At the police station I received a call from the Wariyapola police to say that six young men with gunshot injuries had got admitted to the Wariyapola hospital. They had told the police that they had been shot by a group of insurgents on the Wariyapola-Kurunegala road and had been able to reach the hospital in the trailer of a hand tractor. I immediately guessed that they could be the insurgents who were shot near the transformer. I explained to the OIC Wariyapola that they were a group of insurgents and to keep them in police custody.

In the evening I received a call from the IGP that he would be arriving in Kurunegala at 8 a.m. accompanied by General Attygalle. He told me that they wanted to have a chat with Leo Perera. I immediately informed Leo and told him to remain in office or at the Police Station in the morning.

By that time I had come to know that several Kurunegala SLFP lawyers had made some serious complaints against the ASP. Leo having received credible information that some of these lawyers were in league with insurgent leaders had not only questioned and cautioned them but even got their houses searched. One special reason for these lawyers to be aggrieved was because three of the insurgents shot dead by Leo when he recaptured the Potuhera Police Station had been local criminals who had been associating closely with them.

When the IGP arrived with the General I met them and brought them to my office. Wing Commander Weeratne, the Co-ordinating officer was also present to meet them. He had made arrangements for an armed escort of airmen to accompany the IGP and the General wherever they went. The undisclosed mission of the two top men was to take Leo back to Colombo with them. The IGP had been pressurized by Minister Felix Dias Bandaranaike to transfer the ASP, but the IGP had decided not to displease and discourage a young officer by making him feel that he had been punished. The IGP was more than conscious of the fact that the ASP had done an excellent job in quelling the insurgency in the Kurunegala District.

Leo was in my office. He was cheerful, calm and collected. The IGP and General Attygalle spoke to him cordially. Over a cup of tea the four of us discussed the happenings in the country. After a few minutes the General turned to Leo and said, “Leo, you have been working very hard. You need some rest and you must come along with us to Colombo”. Leo smiled, looked down and calmly responded, “Sir, thank you for the compliment, but let me say that this is not the time to rest, there’s plenty of work to be done”. He then went on to explain the underhand manner in which three lawyers, mentioning their names, who pretended to be great supporters of the government were acting. He went on to emphasize that he even had proof how they were hand in glove with insurgents and local criminals.

The IGP and Attygalle were conspicuously silent. After a few moments Leo spoke again. He said: ” If I come with you now, all these rascals will think that I was arrested and taken to Colombo. I will come to Police Headquarters on my own. Shall drive down this afternoon”.

Soon after the IGP and General Attygalle had left, at about 11 a.m. a high level team of investigators arrived from Colombo. This team consisted of Kenneth Seveniratne, Director of Public Prosecutions; Francis Pietersz, Director of Establishments and Cyril Herath, Director of Intelligence. Their mission was to carry out a general investigation into the happenings in Kurunegala. They were all my friends; my task was to give them whatever assistance they required. They were billeted with the Airforce and worked mainly from my office. They visited several places including the Kurunegala, Potuhera and Mawathagama police stations; and the Rest House which had been the meeting place and ‘watering hole’ of some of the lawyers during the height of the troubles. Many lawyers and several police officers were also questioned by them. They completed their assignment after about a week and left for Colombo.

Significantly they had not been able to find evidence of any wrongdoing by ASP Leo Perera. Before long I too was recalled to Colombo and asked to resume duties as the Director of Police Planning & Research. From this position too I was able to make useful contributions to the rehabilitation effort and particularly the fair and equitable distribution of the Terrorist Victim’s Fund.

Features

A 20-year reflection on housing struggles of Tsunami survivors

Revisiting field research in Ampara

by Prof. Amarasiri de Silva

The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, also known as the Boxing Day tsunami, triggered by a magnitude 9.1 earthquake off the coast of Sumatra on 26 Dec., 2004, had a catastrophic impact on Sri Lanka. It is estimated to have released energy equivalent to 23,000 Hiroshima-type atomic bombs, wiping out hundreds of communities in minutes. The tsunami struck Sri Lanka’s eastern and southern coasts approximately two hours after the earthquake. The eastern shores, facing the earthquake’s epicenter, bore the brunt of the waves, affecting settlements on the east coast. The tsunami displaced many families and devastated villages and communities in the affected districts of Sri Lanka. Although Boxing Day is associated with exchanging gifts after Christmas and was a time to give to the less fortunate, it brought havoc in Sri Lanka to many communities. It resulted in approximately 31,229 deaths and 4,093 people missing. In terms of the dead and missing numbers, Sri Lanka’s toll was second only to Indonesia (126,804, missing 93,458, displaced 474,619). Twenty-five beach hotels were severely damaged, and another 6 were completely washed away. More than 240 schools were destroyed or sustained severe damage. Several hospitals, telecommunication networks, coastal railway networks, etc., were also damaged. In addition, one and a half million people were displaced from their homes.

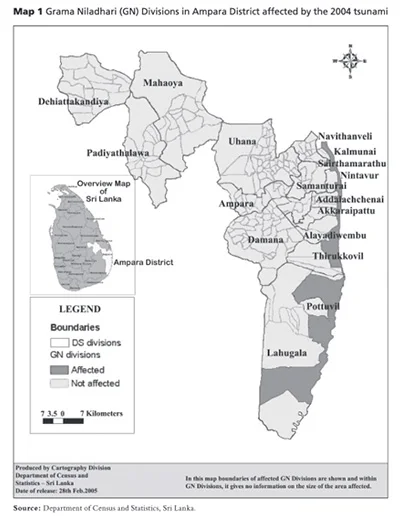

Ampara district was a hard-hit district, where more than 10,000 people died. A Galle bound train from Colombo, carrying about 1,700 passengers visiting their ancestral homes and villages, on the Sunday after the Christmas holidays, was struck by the tsunami near Telwatta; most of them were killed.

About 8,000 people were killed in the northeast region, which the LTTE controlled at the time. The Ampara district was a hard-hit district, with more than 10,000 people dying and many more displaced. In sympathy with the victims, the Saudi Arabian government established a grant to construct houses to assist 500 displaced families in Ampara in 2009. The Saudi Envoy in Colombo presented the house keys to President Mahinda Rajapaksa in 2011 for distribution to tsunami victims in the Ampara district. However, due to the protests by local majoritarian ethnic groups, the government intervened, and a court ruling halted the housing distribution to the victims, mandating that houses be allocated according to the country’s population ratio. The project includes residential units and amenities such as a school, a supermarket complex, a hospital, and a mosque, making it unique for Muslim people. Saudi government ambassador Khalid Hamoud Alkahtani engaged in discussions with the Sri Lankan government to sort out the issues and agreed to give the houses to the respective victims.

Immediate Recovery

The immediate relief work was initiated just after the disaster, and the government had financial and moral support from local people and countries worldwide. As most displaced people were children and women, restoring at least basic education facilities for affected children was a high priority. By mid-year, 85 percent of the children in tsunami-affected areas were back in school, which showed that the relief programme in school education was a success.

Relief efforts for households included the provision of finances to meet immediate needs. Compensation of Rs.15,000 (US$150) was offered for victims towards funeral expenses; livelihood support schemes included Payment of Rs.375 (US$3.75) in cash and rations for each member of a family unit per week, a payment of Rs. 2,500 (US$25) towards kitchen utensils per family. These initial measures were largely successful, though there were some problems with a lack of coordination, as witnessed. (See Map 1)

The most considerable financing needs were in the housing sector. The destruction of private assets was substantial (US$700 million), in addition to public infrastructure and other assets. Loss of current output in the fisheries and tourism sectors—which were severely affected—was estimated at US$200 million and US$130 million, respectively.

2004 tsunami-impacted zone. (Image courtesy Reliefweb)

Strands of Hope: Progress Made for Tsunami-Affected Communities of Sri Lanka

By mid-June 2005, the number of displaced people was down to 516,000 from approximately 800,000 immediately after the tsunami, as people went home—even if the homes in question were destroyed or damaged—and were taken off the books then. At first, an estimated 169,000 people living in schools and tents were mainly transferred to transitional shelters/camps—designed to serve as a stopgap between emergency housing and permanent homes. This transitional shelter was only supplied to affected households in the buffer zone.

By late August 2005, The Task Force for Rebuilding the Nation (TAFREN) estimated that 52,383 transitional shelters, accommodating an estimated 250,000 tsunami-affected people, had been completed since February 2005 at 492 sites. Those transitional housing programme shelters were expected to be completed with 55,000 by the end of September 2005. This goal seems more than achievable. I did not find evidence to show that it has been achieved.

I did my field research in Ampara district with support from UNDP Colombo, the Department for Research Cooperation, and the Swedish International Development Cooperation.

My research shows that the tsunami affected families in Muslim settlements along the East Coast had a severe housing problem for two reasons.

• First, the GoSL has declared that land within 65 meters of the sea is unsafe for living due to possible seismic effects, and people are thus prohibited from engaging in any construction in that beach area. This land strip is the traditional living area of the Muslims, particularly the fisher folk. Families living along the narrow beach strip have not been offered alternative land or adequate compensation to buy land outside the 65-metre zone.

• Second, the LTTE has prohibited Muslims from building houses on land purchased for them by outside agencies on the pretext that it belongs to the Tamils.

The GoSL established several institutions as a response strategy for post-tsunami recovery after the failure of P-TOMS. The Task Force for Rebuilding the Nation (TAFREN), the Task Force for Relief (TAFOR), and the Tsunami Housing Reconstruction Unit (THRU) were the lead agencies created through processes involving private and public sector participation. In November 2005, following the election of President Mahinda Rajapaksa, the Reconstruction and Development Agency (RADA)was set up. This became an authority with executive powers following the parliamentary ratification of the RADA Act in 2006. RADA’s mandate was to accelerate reconstruction and development activities in the affected areas, functionally replacing all the tsunami organizations and a significant part of the former RRR Ministry. According to RADA, the total number of houses built so far (as of May 2006) in Ampara is 629, while the total housing units pledged is 6,169. At the time of the research (March to June 2006), no housing projects were completed in a predominantly Muslim area.

Compensation for damaged houses was not based on a consistent scheme. As a result, some families received large sums, while others did not get any money. In some instances, those who collected compensation were not the affected families. The Auditor General, S.C. Mayadunne, noted that Payment of an excessive amount, even for minor damages, is due to the payments being made without assessing the cost of restoring the houses to normal condition. (For example, Rs. 100,000 had been paid for minor damages of Rs. 10,000) … Payments made without identifying the value of the damaged houses, thus resulting in heavy expenditure by the government (For example, a sum of Rs. 250,000 had been paid for the destruction of a temporary house valued at Rs. 10,000) (Mayadunne, 2005, p. 8). That compensation was not paid according to an acceptable scheme, which led to agitation among the affected people and provided an opportunity for political manipulation. The LTTE and the TRO requested direct aid for reconstruction work in LTTE-controlled areas. The poor response of the GoSL to this demand was interpreted as indifference on its part towards ethnic minorities in Ampara. Meanwhile, the GoSL provided direct support for tsunami-affected communities in southern Sri Lanka, where the majority were Sinhalese, strengthening this allegation.

Land scarcity in tsunami-affected Ampara and disputes over landownership in the area were the main reasons for not completing the housing programmes. The LTTE contended that the land identified for building houses by the GoSL or purchased by civil society organisations for constructing such houses belongs to the Tamils, an ideology based on a myth of their own, a Tamil hereditary Homeland—paarampariyamaana taayakam’ (Peebles, 1990, p. 41). Consequently, housing programmes could not be implemented at that time.

The land question in the Eastern Province has a history that dates back to 1951 when the Gal Oya Colonisation scheme was established. According to the minority version of this history, in a report submitted by Dr. Hasbullah and his colleagues, it shows that the colonists were selected overwhelmingly from among the Sinhalese rather than the Muslims and Tamils, who were a majority in Ampara at that time, and, as a result, the ethnic balance of Ampara District was disrupted. However, conversely, B.H. Farmer reported in 1957 that Tamils, especially Jaffna Tamils, were ‘chary’ and did not have a ‘tradition of migration,’ which was the apparent reason for less Tamil representation among the colonists of Gal Oya. According to Farmer, up to December 31, 1953, between five and 16 percent of the colonists were chosen from the Districts of Batticaloa, Jaffna and Trincomalee, predominantly Tamil. Contradictory evidence (with a political coloring following the recent rise of ethnicity in this discourse) reports by Dr. Hasbullah that 100,000 acres of agricultural land in the East have been ‘illegally transferred from Muslims to the Tamils’ since the 1990s. The Tamils, however, believe that the land in the Eastern Province is part and parcel of the Tamil Homeland. This new political ideology of landownership that emerged at that time in the ethnopolitical context of the Eastern Province has intensified land (re)claiming in Ampara by Muslims and Tamils.

According to Tamil discourse, the increase in the value of land in Ampara over the past two decades has led to rich Muslims purchasing land belonging to poor Tamils, resulting in ethnic homogenization in the coastal areas of the District in favor of the Muslims. ‘Violence against Tamils was also used in some areas to push out the numerically small Tamil service caste communities’ as Hasbullah says. In a situation with an ideological history of land disputes, finding new land for the construction of houses for Muslim communities affected by the tsunami posed a challenge at that time.

In the face of this challenge, Muslims in Ampara sought assistance from Muslim politicians and organisations that willingly came forward to assist them. The efforts made by these politicians and civil society organisations to erect houses for tsunami-affected Muslim families were forcibly curtailed by the LTTE. Consequently, a proposed housing program for Muslims in Kinnayady Kiramam in Kaththankudi was abandoned in 2005. Development of the four acres of land bought by the Memon Sangam in Colombo for tsunami victims of Makbooliya in Marathamunai was prohibited in 2005. Similar occurrences have been reported in Marathamunai Medduvedday. Mrs. Ferial Ashraff, at that time Minister of Housing and Common Amenities, wanted to build houses in Marathamunai, Periyaneelavanai DS division (Addaippallam), the Pandirippu Muslim area, and in Oluvil–Palamunai, but the LTTE proscribed all such initiatives.

In the face of this challenge, Muslims in Ampara sought assistance from Muslim politicians and organisations that willingly came forward to assist them. The efforts made by these politicians and civil society organisations to erect houses for tsunami-affected Muslim families were forcibly curtailed by the LTTE. Consequently, a proposed housing program for Muslims in Kinnayady Kiramam in Kaththankudi was abandoned in 2005. Development of the four acres of land bought by the Memon Sangam in Colombo for tsunami victims of Makbooliya in Marathamunai was prohibited in 2005. Similar occurrences have been reported in Marathamunai Medduvedday. Mrs. Ferial Ashraff, at that time Minister of Housing and Common Amenities, wanted to build houses in Marathamunai, Periyaneelavanai DS division (Addaippallam), the Pandirippu Muslim area, and in Oluvil–Palamunai, but the LTTE proscribed all such initiatives.

The Islamabad housing scheme in Kalmunai Muslim DS division and the construction of houses by Muslim individuals in Karaithivu were banned, and threats were issued by the LTTE and a Tamil military organisation called Ellai Padai (Boundary Forces). Because the GoSL and the intervening agencies could not resolve the housing problem, the affected communities became disillusioned and lost confidence in the GoSL departments, aid agencies, and international NGOs. Much effort and resources were wasted in finding land and designing housing programmes that have not materialised. Some funds pledged by external agencies failed to materialise, causing harm to low-income families. Efforts to provide housing for tsunami-affected people in the Ampara District at that time highlighted their vulnerability to LTTE threats and the power politics of participating agencies. Regarding housing and land issues, the Muslim people of Ampara adopted two approaches to address their challenges. First, in some cases, they reached a compromise with the LTTE, agreeing that upon completion of a housing project, a portion of the houses would be allocated to the Tamil community under LTTE supervision.

For instance, this approach proved successful in the Islamabad housing programme, which was halfway complete as of the time of the research (March–June 2006). Similarly, a housing scheme in Ninthavur followed a comparable compromise with the LTTE. According to Mohamed Mansoor, the then President of the Centre for East Lanka Social Service, 22 of the 100 houses were to be allocated to the Tamil community upon completion. This allocation was deemed reasonable because Muslims owned 80 percent of the land in the area, while Tamils owned 20 percent. At the time of the author’s fieldwork, approximately 30 houses had been completed at this site. I don’t know what happened afterward.

The second approach adopted by the people was to build houses in the areas they had lived in before the tsunami, despite construction being prohibited within 65 meters of the sea. Muslims in Marathamunai knew they would not be allocated any land for housing and sought funds from organisations such as the Eastern Human Economic Development to construct homes on their original plots. The affected individuals have made efforts to urge their leaders to engage with the TRO and the LTTE to reclaim the funds borrowed by Muslim people and organisations to purchase land. The four-acre plot that the Memon Society had acquired for housing development was sold to a Tamil organisation for Rs. 1,000,000 (roughly USD 10,000) and was one such land in question.

The national political forces operating in Ampara have deprived the poor (Muslim) fisher folk of their right to land and build houses in their villages. These communities have resorted to non-violent strategies involving accepting the status quo without questioning it and fighting for their rights. The passivity among the poor affected families is a result of them not having representation in the civil society organisations in the area. These bodies are run by elites who do not wish to contest the GoSL rule of a 65-metre buffer zone or LTTE land claims. The tsunami not only washed away the houses and took the land of the poor communities that lived by the sea, but it also made them even poorer, more marginalised, and more ethnically segregated.

Here, 20 years later, it is time that justice was done to the Muslim families in the Ampara district who were severely hit by the tsunami. It is also a significant and timely commitment made by President Dissanayake to offer 500 houses to the Muslim tsunami victims. Such a promise is overdue and essential, as these marginalised communities have desperately needed a voice and action in their favour for over 20 years. Delivery of such homes to the victims would be an important step in restoring social harmony and the dignity and livelihoods of those affected by the tragic incident.

Features

Worthless corporations, boards and authorities

Prof. O. A. Ileperuma

The Cabinet has recently decided to review the state-owned, non-commercial institutions, many of which are redundant or are of no use. The government manages 86 departments, 25 District Secretariats, 339 Divisional Secretariats, 340 state-owned enterprises and 115 non-commercial state statutory institutions. The national budget allocates Rs. 140 billion to manage these institutions.

We have inherited a large number of redundant Corporations, Boards and Authorities causing a huge drain on our financial resources. These institutions were basically created by previous governments to give jobs to defeated candidates and friends of government politicians. For instance, we have the State Pharmaceutical corporation and the State Pharmaceutical Manufacturing corporation. They can be merged. Then, we have the Coconut Development authority and the Coconut Cultivation Board, which is redundant. Decades ago, coconut cultivation came under the coconut research institute (CRI). An extension section of the CRI can easily undertake the functions of these two institutions. Another example is the still existing Ceylon Cement corporation which earlier ran two cement mills at Puttalam and Kankesanthurai. Now, the Kankasenthurai factory does not exist and the Puttalam factory is under the private sector. Still this Ceylon Cement Corporation exists and the only activity they are doing is to lease the lands for mining which earlier belonged to them. There is a chairman appointed by the minister in charge based on political connections and a general manager and a skeleton staff of about ten workers. This corporation can be easily dissolved and the Ministry Secretary can take up any functions of this corporation.

In the field of sciences, the National Science Foundation was created in 1968 to promote science and technology and to provide funding for researchers. Then a former president created two other institutions, National Science and Technology Commission (NASTEC) and National research Council (NRC). While NASTEC is tasked with science policy and NRC provides research grants; both these tasks were earlier carried out by the National Science Foundation. In the field of education, curriculum revisions, etc., were carried out earlier by the Department of Education, and later the National Institute of Education was created, and for educational policy, the National Education Commission was created. The latter was created to provide a top position for an academic who supported the then government in power.

There is a Water Supply and Drainage Board and also a separate Water Resources Board, and they can easily be amalgamated. There is also the Cashew corporation serving no useful purpose and its duties can be taken over by an institution such as the Department of Minor Crops. There is also the State Development & Construction Corporation and the State Engineering Corporation of Sri Lanka which appear to be doing similar jobs.

We still have Paranthan Chemicals Ltd., which is the successor to the Paranthan Chemicals Corporation involved in manufacturing caustic soda and chlorine. Their factory was destroyed during the war nearly 20 years ago, but it exists and its only function is to import chlorine and sell it to the Water Board for the water purification process. Why can’t the Water Board import chlorine directly?

I am aware that my views on this subject are likely to draw criticism but such redundancies are a severe drain on the Treasury, which faces the difficult task of allocating funds.

Features

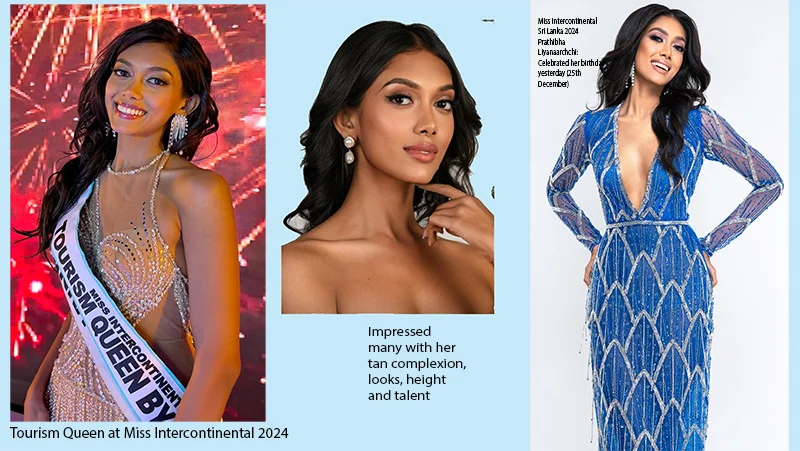

Head-turner in Egypt…

Prathibha Liyanaarchchi, Miss Intercontinental Sri Lanka 2024, is back in town after participating in the 52nd edition of Miss Intercontinental held at the Sunrise Remal Resort, Sharm El-Sheik, in Egypt.

Prathibha Liyanaarchchi, Miss Intercontinental Sri Lanka 2024, is back in town after participating in the 52nd edition of Miss Intercontinental held at the Sunrise Remal Resort, Sharm El-Sheik, in Egypt.

There were nearly two weeks of activities, connected with this event, and Prathibha says she enjoyed every minute of it.

“It was wonderful being in the company of over 52 beautiful girls from around the world and we became great friends.

“My roommate was Miss Greece. She was simply awesome and I even taught her a few Sinhala words.

“Most of the contestants were familiar with Ceylon Tea but didn’t quite know much about Sri Lanka.”

However, having won a special award at Miss Intercontinental 2024 – Queen of Tourism – Prathibha says she is seriously thinking of working on a campaign to show the world that Sri Lanka is a paradise island and that tourists would love to experience our scene.

Although our queen was not in the final list, she made it into the Top 22 and was quite a drawcard wherever she went.

“I guess it was my tan complexion and my height 5 ft. 10 inches.”

She even impressed an international audience with her singing voice; the organisers were keen to have a contestant from the Asia Oceania group showcase her talent, as a singer, and Prathibha was selected.

She sang Madonna’s ‘La Isla Bonita’ and was roundly applauded.

Even in the traditional costume section, her Batik Osariya and the traditional seven-piece necklace impressed many.

With her new buddies…at the beauty pageant

The grand finale was held on 6th December with Miss Puerto Rico being crowned Miss Intercontinental 2024.

“I would like to say a big thank you to everyone who supported me throughout this journey. I’m honoured to have been named a Top 22 Finalist at Miss Intercontinental 2024 and awarded the Special title of Miss Tourism Queen. It was a challenging yet unforgettable experience competing in Egypt. Preparing, in just three weeks, and performing, was no easy feat, but I’m so proud of what I accomplished.”

For the record, Prathibha, who celebrated her birthday on Christmas Day (25), is a technical designer at MAS holdings, visiting lecturer, model, and a graduate from the University of Moratuwa.

Unlike most beauty queens who return after an international event and hardly think of getting involved in any community work, Prathibha says she plans to continue serving her community by expanding her brand – Hoop The Label – and using it as a platform to create a positive change for the underprivileged community.

“At the same time, I am committed to furthering my education in fashion design and technology, aiming to combine creativity with innovation to contribute to the evolving fashion industry. By blending these passions, I hope to make a lasting impact, both in my community, and in the world of fashion.”

-

Sports7 days ago

Sports7 days agoSri Lanka to mend fences with veterans

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoPathirana set to sling his way into Kiwi hearts

-

Opinion7 days ago

Opinion7 days agoIs AKD following LKY?

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoOffice of CDS likely to be scrapped; top defence changes on the cards

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoSL issues USD 10.4 bn macro-linked bonds

-

Opinion7 days ago

Opinion7 days ago‘A degree is not a title’ – a response

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoRanil’s advice

-

Editorial7 days ago

Editorial7 days agoLest watchdogs should become lapdogs