Features

Did the Air Vice Marshall miss his flight?

This article responds to Air Vice Marshall (retired) Sosa’s article titled, ‘How did the pearl of the Orient miss the bus?’ which appeared in the Sunday Island of Feb. 28, 2021. This response is made not as a means to ridicule or denigrate his efforts, which appear to have been penned from a patriotic sentiment in asking aloud introspectively, where as a nation, did we go wrong? In arriving at conclusions however, he appears to have been so thoroughly misled into believing certain twisted and deliberately distorted versions of history.

With such flawed understanding he goes on to make historically inaccurate claims. Every second line almost amounts to gross fabrications that I have decided to correct, thus rectifying these utterances, not by unsubstantiated and sweeping statements through authoritative documented evidence.

The Vice Marshall does injustice primarily to himself in accepting certain propositions without bothering about their veracity. In damning national personalities of our country who have in the past, in stark variance to the politicos of today, rendered yeoman service he belittles the value of the precious. This perspective emanating from an ignoramus may be tolerated, but not from one such as the writer.

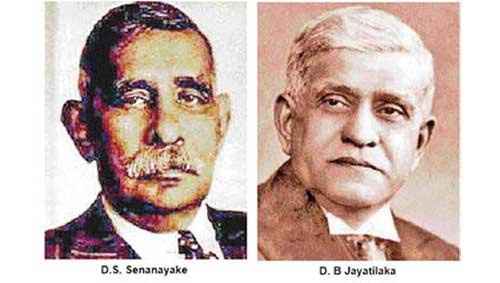

The Temperance Movement in Ceylon is a suitable point from which to begin, for it was from that body that rose the public personalities of D.B. Jayatilaka and D.S. Senanayake. This movement was founded in defiance to the Toddy Act of 1912, which aimed at mushrooming bars and liquor vending outlets throughout Ceylon. The Buddhist and Hindu communities were largely outraged, and saw in it the dangers that could befall the populace. The colonial government however, viewed this opportunity as one which would assist in filling their coffers.

The opposition to the Act, mainly came through Temperance leaders such as the Senanayake brothers ( D.S, F.R, and D.C) and D. B Jayatilaka and others inclusive of W.A .De Silva and the Hewavitharana brothers. This resulted in the boycotting of the taverns by the native populace. Hulugalle wrote in his D.S. Senanayake biography, “The Temperance movement gathered strength and the zest and the driving force which the younger Senanayake brought to it in his home surroundings at Botale. The Whole of Hapitigama Korale with its centre at Mirigama, had not a single tavern…

Thus, when some time later in 1915, a riot broke out between Muslims and Sinhalese, and martial law was used to quell the situation, it seemed incredible that almost all of the leaders of the temperance movement were arrested and incarcerated on little or no evidence as being connected or proximate to the riot. These respected leaders were unduly humiliated and subjected to degrading cruelties. The statements given by each of them is worth reading, and in particular the meticulous record kept by Sir Ponnambalam Ramanathan in his book Riots and Martial Law in Ceylon 1915. In the interests of brevity I shall confine myself to parts of statements given by D.S. Senanayake, F.R. Senanayake and D.B. Jayatilaka

D.S. Senanayake, introducing himself as a proprietary planter and plumbago mine owner, living in Cinnamon Gardens, went on to say, “The Town Guard and the Inspector of Police, then made careful search of the premises, but found no incriminating documents or firearms… A fortnight after this search, in the early morning of the 21st, I was awakened by a Town Guard who informed me I was under arrest, and would not permit me to answer a call of nature.”

“After they had searched me, I was taken inside the jail and locked in a bare cell. For want of a chair or bench I had to stand inside this for some hours… Mr. Allnutt who, after informing me that I was at liberty to make a statement proceeded to question me, obviously for the purpose of getting some statement likely to incriminate myself and others. Since I was aware of nothing to incriminate any respectable person, I was not in a position to help him.”

“Our midday meals were pushed inside the room. The very sight of the dirty food and the vessels in which it was served disgusted me, and naturally I was unable to take that food.…… on the 5th August, after 46 days of incarceration under as unpleasant circumstances as one could imagine, I was let out.”

The following accounts of his brother F.R. and of friend and colleague D.B. Jayatilaka are also noteworthy. F.R. introducing self as a graduate of Cambridge University, a Barrister at law, and an elected member of the Colombo Municipal Council said thus. “In the ward in which we were placed there are 150 cells, usually occupied by 150 convicts, but owing to the extraordinary circumstances the jail authorities, seeing the accommodation insufficient, found themselves compelled to shelter during the night over a thousand persons in this building. The temporary sanitary arrangements made for such a multitude, and the overcrowding, naturally made life almost unbearable.”

D.B. Jayathilaka also highlighted that “the fresh air was befouled by the unbearable smells emanating from the lavatories. They were filthy and foul.” He also referred to the manner in which he and his friend D.S. Senanayake whiled away the hours. “I whiled away the time by reciting from memory endless verses which I had learnt from the Pirivena. So did D.S. Senanayake, who sang carters’ songs, miners’ songs and folk songs.”

There was a silver lining in their cloud, for the Senanayake’s, and Jayatilake were subsequently released as heroes of the masses. Unfortunately however, a bright star among them was court martialled and shot dead by firing squad. This was of course the youthful Henry Pedris. Although no appeal existed at the time, a subsequent investigation revealed his innocence. So at this point, I must once again take exception to the Vice Marshall and his sweeping statement that Ceylon’s independence was gained on a platter and with no angry bullet. I doubt the brave young Pedris would have viewed the bullet that shed his innocent youthful blood as a friendly one!

Furthermore he goes on to conjecture rather unfairly and uncharitably that D.S. Senanayake was instrumental in elbowing his lifelong friend Jayatilake out of his seat as vice chairman of the Board of Ministers, only so that he could occupy it. If he had only read (which I know from his conjecture he has not) of the extents the Senanayake brothers went to, for Jayatilaka, including mortgaging the matrimonial home to build ‘Mahanil’ the building on the Y.M.B.A land in furtherance of Jayatilaka’s vision to which they too subscribed, he would understand D.B. and the Senanayake’s were bonded deeply in spirit.

One person who clearly knew and was a close friend of Jayatilaka, as much as of D.S and also of personalities like D.R. Wijewardena, Sir John Kotelawala and even S.W.R.D was the diplomat and the journalist par excellence Herbert Hulugalle. In his writings of them and the times, one actually gets a true glimpse of firsthand accounts and not conjecture inflamed by fantastic conspiracy theories. In Hulugalle’s ‘Selective Journalism’ he explains who Jayatilaka was, and also what he later became, due to age and human frailty and for no other earthly fault.

No one can be fairer to Jayatilaka, as Hulugalle is for this is what he says, “He seemed to reflect in his life all that is best in our culture, in the Buddhist tradition and in oriental philosophy, and possessed in full measure those gifts and graces which characterize a civilized person such as tolerance, fair play and compassion.” But he notes “Although Jayatilaka never lost the mastery of the State Council, when he reached his seventies, he had lost a great deal of his fire. He was easy-going and lenient. He had lost the sureness of his touch, and signed papers which he had not read”

In 1939, Jayatilaka was the vice chairman of the board of Ministers in the Council. He had also become the president of Ceylon’s largest political forum; the Ceylon National Congress. He was at this time 72 years in age. The Ceylon National Congress itself had attracted to its fold many young legal luminaries that in later years were to become prominent in Ceylon’s destiny. J.R. Jayewardene, Edwin Wijeyeratne and R.G. Senanayake were amongst them. S.W.R. D. though not directly a member had affiliated his organization the Sinhala Maha Sabha, to it.

That same year Jayatilaka’s unblemished reputation suffered a serious setback in what became known as the Bracegirdle affair, this situation was ongoing from as far back as 1937. M.A.L. Bracegirdle was an Australian Marxist who found his way to Ceylon and engaged in what the colonial government saw as hostile activity. While the Governor had liaised with the chief of police, a Mr. Banks to deport him from Ceylon, the LSSP had sought a writ of habeas corpus from the Supreme Court, to avoid the very same. The legal position was that the Governor had no right to act in such a manner, unless authorized by the relevant minister who happened to be D.B. Jayatilaka. The police chief in evidence stated that everything was done under the minister’s concurrence, but the minister denied any knowledge.

In the fracas that ensued, the Governor had appointed a commission under the supervision of a retired Supreme Court judge to investigate and produce to him a report. The findings of the report entirely exonerated the police chief which had the indirect effect of casting Jayatilaka in unfavourable light. Since the testimonies of the police chief and his immediate boss Minister Jayatilaka were at variance, Jayatilaka went on record, stating many times, including to the Congress that he would rather resign from State Council, than have to work with Banks again. Since the Commission’s report was entirely weighted in favour of Banks, it was then impossible for the Governor to remove him from that position even if he wanted to.

A few skeptics had voiced that perhaps Jayatilaka ought to step down but the board of Ministers led by Senanayake strongly backed Jayatilaka even to the extent of passing a motion of confidence in Jayatilaka and then making scathing attacks on the Commission’s report mainly alleging bias and finally passing a motion of censure upon its findings in the State Council. This is hardly the manner in which a person waiting to elbow out another would act! The Vice Marshall may if he chooses, go through the State Council deliberations and decide for himself.

Jayatilaka’s statements however, to the Congress had not been forgotten, nor allowed to die a natural death. It seemed to the young men of Congress that consequent to the Commission’s report and contrary to what he had said before, Jayatilaka would compromise his dignity and continue to work with Banks. At this Juncture, the youngsters had begun taking control of congress and youthful J.R. Jayewardene was elevated to the position of secretary. Jayewardene demanded his resignation.

I quote from K.M.De Silva’s J.R. Jayewardene of Sri Lanka 1906- 1956 (the first fifty years ) . “When the Congress Committee met on 23rd January they did so in the verandah of Jayatilaka’s house – The Congress had no home of its own, and its committee meetings were held in the residence of the incumbent president, and the principle business of the day was to discuss a resolution moved by E. A. P Wijeyeratne that D.B.Jayatilaka should vindicate his honour by resigning.” (Not from the Congress but the State Council). J.R. fully in support of this view explained, “It was to help Sir Baron to resign, to take a step which he had determined upon doing, which he had promised to do, that a few of us suggested to him. (pages 47-48 of J.R.Jayewardena, the unpublished memoirs contain the full speech)

Further illumination of the events that finally did lead to his resignation a few years later may be found in D.S. A political biography by K.M. De Silva, at chapter 15. “D.S was 17 years younger than D.B. Jayatilaka…….. A second point which is ignored by political observers is that both D.B. Jayatilaka and D.S entered the national legislature for the first time in the same year, 1924.”

” Among D.B. Jayathilaka’s contributions to public life in the country was his role in the establishment of the Sinhala Etymological Dictionary… The work he did in establishing the dictionary naturally attracted attention and in the case of some observers, much praise. He had his critics as well and one of them D C W Abeysekera took legal action against him on the charge that he had accepted payment as editor while being a member of the Legislative Council. Abeysekera claimed Rs23,000 as damages and urged that this should include vacation of his (Jayatilaka’s) seat in the Legislative Council.

In a prolonged legal dispute Abeysekera won the day. It required an Act of Indemnity by the Privy Council in London to save Jayatilaka. When he finally did retire in 1941 he was 73 whereupon he was entrusted with the first Ceylonese diplomatic mission overseas. It was a highly presumptuous and a thoroughly puerile view to take that in 1941, Senanayake saw independence being round the corner and feared that if 73-year old Jayatilaka was around he may have to become Ceylon’s first prime minister instead of him. As it turned out, and if the Vice Marshall could add and subtract as well as he conjectures and imagines, Independence came seven years hence and had Jayathilake lived for that long he would have been an octogenarian. The 40’s decade was neither as medically or scientifically advanced as today, and when Jayatilaka passed away in 1944 at the age of 76 he had more than passed the natural life expectancy of the average Ceylonese. It is not directly relevant but interesting to note that when Senanayake died in March 1952 he was only 68.

Senanayake, was the young pup of the independence movement. He was taken very seriously by the masses upon his wrongful incarceration and relied upon more, after the death of his much respected older brother F.R. He was in the thick of the independence struggle along with all the national leaders, but due to age being on his side, he was the only one still there to see its final result ; an independent Ceylon. He is referred to as the Father of the Nation, because at the time of Independence he was the main negotiator and undisputed leader among them. The unique position he was in was not of his design but a design of nature.

When considering some of the other national heroes of the independence movement chronologically we notice the following. Henry Pedris was murdered by the British in 1915. F.R.Senanayake on his way back from Buddha Gaya passed away in India of appendicitis in 1926. Ponambalam Ramanathan died on pilgrimage in 1930. Sir James Pieris too in 1930, W.A. De Silva passed away in 1942, and Sir D.B. Jayatilaka in 1944.

All these personalities mentioned in the previous paragraph contributed much to the well-being of their nation through selfless sacrifice. Some of them particularly D.B. Jayatilaka, D.S.Senanayake and Sir John Kotalawala bequeathed personal wealth and property to the State. The edifices of Thurban House, D.S.Senanayake school in Colombo 7 and the Kotalawala Defence University, all attest to the memory of men that put the nation before themselves.

Features

Rebuilding the country requires consultation

A positive feature of the government that is emerging is its responsiveness to public opinion. The manner in which it has been responding to the furore over the Grade 6 English Reader, in which a weblink to a gay dating site was inserted, has been constructive. Government leaders have taken pains to explain the mishap and reassure everyone concerned that it was not meant to be there and would be removed. They have been meeting religious prelates, educationists and community leaders. In a context where public trust in institutions has been badly eroded over many years, such responsiveness matters. It signals that the government sees itself as accountable to society, including to parents, teachers, and those concerned about the values transmitted through the school system.

This incident also appears to have strengthened unity within the government. The attempt by some opposition politicians and gender misogynists to pin responsibility for this lapse on Prime Minister Dr Harini Amarasuriya, who is also the Minister of Education, has prompted other senior members of the government to come to her defence. This is contrary to speculation that the powerful JVP component of the government is unhappy with the prime minister. More importantly, it demonstrates an understanding within the government that individual ministers should not be scapegoated for systemic shortcomings. Effective governance depends on collective responsibility and solidarity within the leadership, especially during moments of public controversy.

The continuing important role of the prime minister in the government is evident in her meetings with international dignitaries and also in addressing the general public. Last week she chaired the inaugural meeting of the Presidential Task Force to Rebuild Sri Lanka in the aftermath of Cyclone Ditwah. The composition of the task force once again reflects the responsiveness of the government to public opinion. Unlike previous mechanisms set up by governments, which were either all male or without ethnic minority representation, this one includes both, and also includes civil society representation. Decision-making bodies in which there is diversity are more likely to command public legitimacy.

Task Force

The Presidential Task Force to Rebuild Sri Lanka overlooks eight committees to manage different aspects of the recovery, each headed by a sector minister. These committees will focus on Needs Assessment, Restoration of Public Infrastructure, Housing, Local Economies and Livelihoods, Social Infrastructure, Finance and Funding, Data and Information Systems, and Public Communication. This structure appears comprehensive and well designed. However, experience from post-disaster reconstruction in countries such as Indonesia and Sri Lanka after the 2004 tsunami suggests that institutional design alone does not guarantee success. What matters equally is how far these committees engage with those on the ground and remain open to feedback that may complicate, slow down, or even challenge initial plans.

An option that the task force might wish to consider is to develop a linkage with civil society groups with expertise in the areas that the task force is expected to work. The CSO Collective for Emergency Relief has set up several committees that could be linked to the committees supervised by the task force. Such linkages would not weaken the government’s authority but strengthen it by grounding policy in lived realities. Recent findings emphasise the idea of “co-production”, where state and society jointly shape solutions in which sustainable outcomes often emerge when communities are treated not as passive beneficiaries but as partners in problem-solving.

Cyclone Ditwah destroyed more than physical infrastructure. It also destroyed communities. Some were swallowed by landslides and floods, while many others will need to be moved from their homes as they live in areas vulnerable to future disasters. The trauma of displacement is not merely material but social and psychological. Moving communities to new locations requires careful planning. It is not simply a matter of providing people with houses. They need to be relocated to locations and in a manner that permits communities to live together and to have livelihoods. This will require consultation with those who are displaced. Post-disaster evaluations have acknowledged that relocation schemes imposed without community consent often fail, leading to abandonment of new settlements or the emergence of new forms of marginalisation. Even today, abandoned tsunami housing is to be seen in various places that were affected by the 2004 tsunami.

Malaiyaha Tamils

The large-scale reconstruction that needs to take place in parts of the country most severely affected by Cyclone Ditwah also brings an opportunity to deal with the special problems of the Malaiyaha Tamil population. These are people of recent Indian origin who were unjustly treated at the time of Independence and denied rights of citizenship such as land ownership and the vote. This has been a festering problem and a blot on the conscience of the country. The need to resettle people living in those parts of the hill country which are vulnerable to landslides is an opportunity to do justice by the Malaiyaha Tamil community. Technocratic solutions such as high-rise apartments or English-style townhouses that have or are being contemplated may be cost-effective, but may also be culturally inappropriate and socially disruptive. The task is not simply to build houses but to rebuild communities.

The resettlement of people who have lost their homes and communities requires consultation with them. In the same manner, the education reform programme, of which the textbook controversy is only a small part, too needs to be discussed with concerned stakeholders including school teachers and university faculty. Opening up for discussion does not mean giving up one’s own position or values. Rather, it means recognising that better solutions emerge when different perspectives are heard and negotiated. Consultation takes time and can be frustrating, particularly in contexts of crisis where pressure for quick results is intense. However, solutions developed with stakeholder participation are more resilient and less costly in the long run.

Rebuilding after Cyclone Ditwah, addressing historical injustices faced by the Malaiyaha Tamil community, advancing education reform, changing the electoral system to hold provincial elections without further delay and other challenges facing the government, including national reconciliation, all require dialogue across differences and patience with disagreement. Opening up for discussion is not to give up on one’s own position or values, but to listen, to learn, and to arrive at solutions that have wider acceptance. Consultation needs to be treated as an investment in sustainability and legitimacy and not as an obstacle to rapid decisionmaking. Addressing the problems together, especially engagement with affected parties and those who work with them, offers the best chance of rebuilding not only physical infrastructure but also trust between the government and people in the year ahead.

by Jehan Perera

Features

PSTA: Terrorism without terror continues

When the government appointed a committee, led by Rienzie Arsekularatne, Senior President’s Counsel, to draft a new law to replace the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA), as promised by the ruling NPP, the writer, in an article published in this journal in July 2025, expressed optimism that, given Arsekularatne’s experience in criminal justice, he would be able to address issues from the perspectives of the State, criminal justice, human rights, suspects, accused, activists, and victims. The draft Protection of the State from Terrorism Act (PSTA), produced by the Committee, has been sharply criticised by individuals and organisations who expected a better outcome that aligns with modern criminal justice and human rights principles.

When the government appointed a committee, led by Rienzie Arsekularatne, Senior President’s Counsel, to draft a new law to replace the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA), as promised by the ruling NPP, the writer, in an article published in this journal in July 2025, expressed optimism that, given Arsekularatne’s experience in criminal justice, he would be able to address issues from the perspectives of the State, criminal justice, human rights, suspects, accused, activists, and victims. The draft Protection of the State from Terrorism Act (PSTA), produced by the Committee, has been sharply criticised by individuals and organisations who expected a better outcome that aligns with modern criminal justice and human rights principles.

This article is limited to a discussion of the definition of terrorism. As the writer explained previously, the dangers of an overly broad definition go beyond conviction and increased punishment. Special laws on terrorism allow deviations from standard laws in areas such as preventive detention, arrest, administrative detention, restrictions on judicial decisions regarding bail, lengthy pre-trial detention, the use of confessions, superadded punishments, such as confiscation of property and cancellation of professional licences, banning organisations, and restrictions on publications, among others. The misuse of such laws is not uncommon. Drastic legislation, such as the PTA and emergency regulations, although intended to be used to curb intense violence and deal with emergencies, has been exploited to suppress political opposition.

International Standards

The writer’s basic premise is that, for an act to come within the definition of terrorism, it must either involve “terror” or a “state of intense or overwhelming fear” or be committed to achieve an objective of an individual or organisation that uses “terror” or a “state of intense or overwhelming fear” to realise its aims. The UN General Assembly has accepted that the threshold for a possible general offence of terrorism is the provocation of “a state of terror” (Resolution 60/43). The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe has taken a similar view, using the phrase “to create a climate of terror.”

In his 2023 report on the implementation of the UN Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy, the Secretary-General warned that vague and overly broad definitions of terrorism in domestic law, often lacking adequate safeguards, violate the principle of legality under international human rights law. He noted that such laws lead to heavy-handed, ineffective, and counterproductive counter-terrorism practices and are frequently misused to target civil society actors and human rights defenders by labelling them as terrorists to obstruct their work.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) has stressed in its Handbook on Criminal Justice Responses to Terrorism that definitions of terrorist acts must use precise and unambiguous language, narrowly define punishable conduct and clearly distinguish it from non-punishable behaviour or offences subject to other penalties. The handbook was developed over several months by a team of international experts, including the writer, and was finalised at a workshop in Vienna.

Anti-Terrorism Bill, 2023

A five-member Bench of the Supreme Court that examined the Anti-Terrorism Bill, 2023, agreed with the petitioners that the definition of terrorism in the Bill was too broad and infringed Article 12(1) of the Constitution, and recommended that an exemption (“carve out”) similar to that used in New Zealand under which “the fact that a person engages in any protest, advocacy, or dissent, or engages in any strike, lockout, or other industrial action, is not, by itself, a sufficient basis for inferring that the person” committed the wrongful acts that would otherwise constitute terrorism.

While recognising the Court’s finding that the definition was too broad, the writer argued, in his previous article, that the political, administrative, and law enforcement cultures of the country concerned are crucial factors to consider. Countries such as New Zealand are well ahead of developing nations, where the risk of misuse is higher, and, therefore, definitions should be narrower, with broader and more precise exemptions. How such a “carve out” would play out in practice is uncertain.

In the Supreme Court, it was submitted that for an act to constitute an offence, under a special law on terrorism, there must be terror unleashed in the commission of the act, or it must be carried out in pursuance of the object of an organisation that uses terror to achieve its objectives. In general, only acts that aim at creating “terror” or a “state of intense or overwhelming fear” should come under the definition of terrorism. There can be terrorism-related acts without violence, for example, when a member of an extremist organisation remotely sabotages an electronic, automated or computerised system in pursuance of the organisation’s goal. But when the same act is committed by, say, a whizz-kid without such a connection, that would be illegal and should be punished, but not under a special law on terrorism. In its determination of the Bill, the Court did not address this submission.

PSTA Proposal

Proposed section 3(1) of the PSTA reads:

Any person who, intentionally or knowingly, commits any act which causes a consequence specified in subsection (2), for the purpose of-

(a) provoking a state of terror;

(b) intimidating the public or any section of the public;

(c) compelling the Government of Sri Lanka, or any other Government, or an international organisation, to do or to abstain from doing any act; or

(d) propagating war, or violating territorial integrity or infringing the sovereignty of Sri Lanka or any other sovereign country, commits the offence of terrorism.

The consequences listed in sub-section (2) include: death; hurt; hostage-taking; abduction or kidnapping; serious damage to any place of public use, any public property, any public or private transportation system or any infrastructure facility or environment; robbery, extortion or theft of public or private property; serious risk to the health and safety of the public or a section of the public; serious obstruction or damage to, or interference with, any electronic or automated or computerised system or network or cyber environment of domains assigned to, or websites registered with such domains assigned to Sri Lanka; destruction of, or serious damage to, religious or cultural property; serious obstruction or damage to, or interference with any electronic, analogue, digital or other wire-linked or wireless transmission system, including signal transmission and any other frequency-based transmission system; without lawful authority, importing, exporting, manufacturing, collecting, obtaining, supplying, trafficking, possessing or using firearms, offensive weapons, ammunition, explosives, articles or things used in the manufacture of explosives or combustible or corrosive substances and biological, chemical, electric, electronic or nuclear weapons, other nuclear explosive devices, nuclear material, radioactive substances, or radiation-emitting devices.

Under section 3(5), “any person who commits an act which constitutes an offence under the nine international treaties on terrorism, ratified by Sri Lanka, also commits the offence of terrorism.” No one would contest that.

The New Zealand “carve-out” is found in sub-section (4): “The fact that a person engages in any protest, advocacy or dissent or engages in any strike, lockout or other industrial action, is not by itself a sufficient basis for inferring that such person (a) commits or attempts, abets, conspires, or prepares to commit the act with the intention or knowledge specified in subsection (1); or (b) is intending to cause or knowingly causes an outcome specified in subsection (2).”

While the Arsekularatne Committee has proposed, including the New Zealand “carve out”, it has ignored a crucial qualification in section 5(2) of that country’s Terrorism Suppression Act, that for an act to be considered a terrorist act, it must be carried out for one or more purposes that are or include advancing “an ideological, political, or religious cause”, with the intention of either intimidating a population or coercing or forcing a government or an international organisation to do or abstain from doing any act.

When the Committee was appointed, the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka opined that any new offence with respect to “terrorism” should contain a specific and narrow definition of terrorism, such as the following: “Any person who by the use of force or violence unlawfully targets the civilian population or a segment of the civilian population with the intent to spread fear among such population or segment thereof in furtherance of a political, ideological, or religious cause commits the offence of terrorism”.

The writer submits that, rather than bringing in the requirement of “a political, ideological, or religious cause”, it would be prudent to qualify proposed section 3(1) by the requirement that only acts that aim at creating “terror” or a “state of intense or overwhelming fear” or are carried out to achieve a goal of an individual or organisation that employs “terror” or a “state of intense or overwhelming fear” to attain its objectives should come under the definition of terrorism. Such a threshold is recognised internationally; no “carve out” is then needed, and the concerns of the Human Rights Commission would also be addressed.

by Dr. Jayampathy Wickramaratne

President’s Counsel

Features

ROCK meets REGGAE 2026

We generally have in our midst the famous JAYASRI twins, Rohitha and Rohan, who are based in Austria but make it a point to entertain their fans in Sri Lanka on a regular basis.

We generally have in our midst the famous JAYASRI twins, Rohitha and Rohan, who are based in Austria but make it a point to entertain their fans in Sri Lanka on a regular basis.

Well, rock and reggae fans get ready for a major happening on 28th February (Oops, a special day where I’m concerned!) as the much-awaited ROCK meets REGGAE event booms into action at the Nelum Pokuna outdoor theatre.

It was seven years ago, in 2019, that the last ROCK meets REGGAE concert was held in Colombo, and then the Covid scene cropped up.

Chitral Somapala with BLACK MAJESTY

This year’s event will feature our rock star Chitral Somapala with the Australian Rock+Metal band BLACK MAJESTY, and the reggae twins Rohitha and Rohan Jayalath with the original JAYASRI – the full band, with seven members from Vienna, Austria.

According to Rohitha, the JAYASRI outfit is enthusiastically looking forward to entertaining music lovers here with their brand of music.

Their playlist for 28th February will consist of the songs they do at festivals in Europe, as well as originals, and also English and Sinhala hits, and selected covers.

Says Rohitha: “We have put up a great team, here in Sri Lanka, to give this event an international setting and maintain high standards, and this will be a great experience for our Sri Lankan music lovers … not only for Rock and Reggae fans. Yes, there will be some opening acts, and many surprises, as well.”

Rohitha, Chitral and Rohan: Big scene at ROCK meets REGGAE

Rohitha and Rohan also conveyed their love and festive blessings to everyone in Sri Lanka, stating “This Christmas was different as our country faced a catastrophic situation and, indeed, it’s a great time to help and share the real love of Jesus Christ by helping the poor, the needy and the homeless people. Let’s RISE UP as a great nation in 2026.”

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoSajith: Ashoka Chakra replaces Dharmachakra in Buddhism textbook

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoDialog and UnionPay International Join Forces to Elevate Sri Lanka’s Digital Payment Landscape

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoThe Paradox of Trump Power: Contested Authoritarian at Home, Uncontested Bully Abroad

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoSubject:Whatever happened to (my) three million dollars?

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoLevel I landslide early warnings issued to the Districts of Badulla, Kandy, Matale and Nuwara-Eliya extended

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoNational Communication Programme for Child Health Promotion (SBCC) has been launched. – PM

-

News2 days ago

News2 days ago65 withdrawn cases re-filed by Govt, PM tells Parliament

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoThe minstrel monk and Rafiki, the old mandrill in The Lion King – II