Features

MARRIAGE TO GERTRUDE WICKRAMASINGHE

CHAPTER 7

Gertrude’s brother-in-law and sister strongly opposed the marriage because I was only a clerk. But she was determined and said she would only marry me or remain a spinster.(N.U. Jayawardena, interview by Roshan Pieris, 1987)

Meeting at the Resthouse

While waiting in Tangalle for his letter of appointment to the clerical service, NU was introduced by an uncle to an important member of the Durava clan who had achieved government recognition – Gate Mudaliyar Norman Wickramasinghe of Gorakana, Moratuwa. He and his wife Caroline and daughter Gertrude Mildred (known as Gertie) planned to stop at the Tangalle Resthouse on their way to Kataragama. The main reason for this visit was to see if NU would be a suitable husband for Gertrude. Marriages during this period were arranged by relatives and elders and did not deviate in terms of caste. Norman and Caroline Wickramasinghe had, no doubt, been on the lookout for bachelors who were bright and with good prospects for advancement.

It was not unusual for young women with some wealth and status to marry educated men of the same caste – even if of humbler social origins – as long as they had good prospects. Sometimes a prospective father-in-law would even finance the education of an intelligent young man, of his own caste, who would later become his son-in-law. One famous case of a ‘dowry scholarship,’ as it was popularly known, was that of James Peiris, a leading political figure of the 1920s. His education at Cambridge was paid for by Jacob de Mel, one of the wealthiest landowners and liquor renters of the time, whose daughter Grace married Peiris.

Caste-consciousness was widely prevalent and did not disappear with capitalist development and modernist trends. While the caste system did not apply in public life or government service where merit was the criterion, caste feelings found expression in private life, especially in the arrangement of marriages. In the public domain (except at election time), caste solidarity was overshadowed by class interests, since the local capitalists included members of all castes. Society was also fractured by disputes of a class nature, in the form of employer-employee conflicts. But ethnicity and caste had not been wholly driven out of people’s minds. This would have been true of NU and his relatives who, while trying to move beyond a traditional status, did not forget their caste origins, especially in the choice of marriage partners. At the same time they were conscious of belonging to the Sinhala-Buddhist community of the South – with its regional identity and history based on the ancient southern civilization of Ruhuna and its kings.

Both Norman Wickramasinghe and his daughter took an immediate liking to NU, a bright young man who appeared set for a career in the public service. Horoscopes were compared and were found to match. Gertrude was keen to marry, and her father gave his consent.

However, her elder sister Winifred and her husband Shelton Pieris, a wealthy landowner, felt that Gertrude should marry someone who occupied a better position in society. They were alarmed that the marriage of Gertrude to a ‘lowly clerk’ would diminish the status of the family, and also suspected that NU would benefit financially from this marriage, since Gertrude was her father’s favourite child. Winifred and her husband placed Norman Wickramasinghe under so much pressure that he reluctantly called off the intended marriage. Gertrude, however, was adamant about marrying NU. Since there was no immediate solution to the problem, the matter was left for the time being (de Zoysa manuscript, p.6).

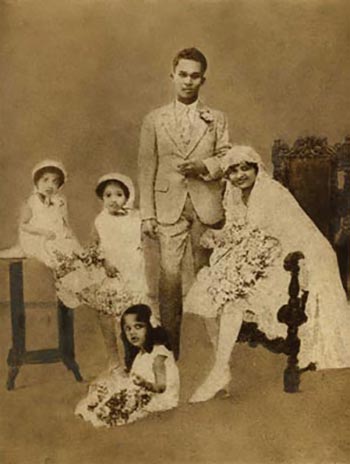

- Wedding photograph of NU and Gertrude

- Gertrude as a young woman

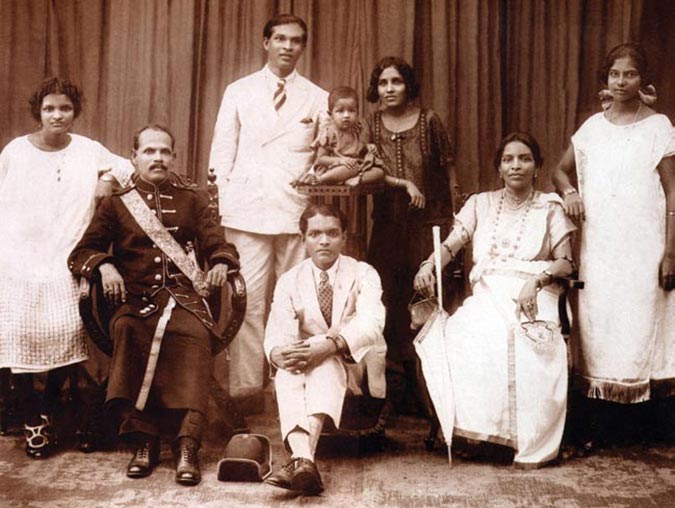

- Gate Mudaliyar Norman and Caroline Wickramasinghe

- Steps to the verandah of the Tangalle Rest house

- The Tangalle Rest house

The Wickramasinghe Clan

Norman Wickramasinghe was from a family of landowners in Matara, who had educated their sons at St. Thomas’ College, Matara. Many of the family were in government service – with several in the next generation going into academia and research. Wickramasinghe joined the government service in July 1894 as fifth clerk at the Fiscal’s Office, Colombo. He made progress and, by 1902, was the Head Clerk of that office. By 1913, as a Class I, Grade II clerk, he had a salary of Rs. 1,980 a year, and ten years later, he was promoted to the Special Class with Rs. 4,500 a year, rising to Rs. 5,500 in 1928. He was promoted to Deputy Fiscal, Colombo and upon his retirement in 1931 the title of Gate Mudaliyar was bestowed on him. (The title “Gate Mudaliyar” was originally given to local officials who were interpreters and translators to the Governor. In later years it was one of the ‘native’ titles awarded for services to government departments. The “symbols of power” attached to the post included a distinctive uniform. (See Patrick Peebles, Social Change in Nineteenth Century Ceylon, 1995, New Delhi, Navrang). Wickramasinghe married Caroline Gunaratne whose father was a well-known surveyor, and no doubt received a good dowry. They had two daughters and a son. Wickramasinghe’s property included a house in Gorakana and two rubber estates of 25 and 50 acres in Avissawella. He gave his daughter Gertrude, the 25-acre estate and his son, the 50-acre estate. Wickramasinghe’s “Wasala Walauwa” was a few miles from Moratuwa, a town that had prospered in the 19th century, renowned for the enterprise of its liquor traders. These traders – mainly from Moratuwa and Panadura – had accumulated large amounts of capital, which they invested in the plantation and graphite sectors, and in education abroad for their sons.

Norman Wickramasinghe’s first cousin was Dionysius Lionel Wickramasinghe (1909-2005) of Panadura, whose sons were the brothers R.H. (Hugh) and P.H. (Percival) Wickramasinghe, both Cambridge graduates in the 1930s. Hugh became a civil servant; and Percival, who was briefly in the Indian Civil Service, upon returning to Sri Lanka became the first non-British Chief Government Valuer. Percival’s son Chandra Wickramasinghe, is an internationally renowned astronomer and Director of the Cardiff Centre of Astro- biology in Britain. Another of Norman Wickramasinghe’s cousins, Wilmot Wickramasinghe, was the father of Dr. Sirima Kiribamune, a former Professor of History at the University of Peradeniya. According to NU’s daughter, Neiliya:

There was always an argument as to whose brains we had inherited – my mother said it was the Jayawardena brains and my father said it was the Wickramasinghe brains. My mother’s second cousins Hugh and Percy

Wickramasinghe were Cambridge Wranglers (with degrees in Mathematics) and my father was very proud of this. (Neiliya Perera, 2006)

This may have made NU all the more determined to obtain a foreign degree himself, and he had the full support of Gertrude in this ambitious venture.

Norman Wickramasinghe’s eldest daughter Winifred’s wedding to Shelton Pieris reflected the elevated status of the Wickramasinghes. It was an era of grand weddings held in the western tradition, but the wedding included a local poruwa ceremony. The national newspapers covered the event, reporting that the civil registration was attested by W.D. Battershill, who was a Deputy Fiscal, and by Abraham de Alwis. One paper reported that:

The cake occupying a room by itself was cut with the bride’s father’s sword and served with champagne… The Eastern Jazz Band… played during the afternoon. Lavish hospitality was dispensed till late in the evening.

The bride was dressed in western attire, popular during the 1920s among young women of notable Sri Lankan families. A newspaper described the bridal wear:

A simple frock of palace silk trimmed with pearls and a large rosette of heather at the waist… with a flowing white georgette veil… Her ornaments were brilliants and pearls, the gifts of her parents, and she carried a butterfly bouquet of May Queen roses. Her going-away dress was of biscuit crepe-de-chine richly trimmed with silk lace, and a hat to match.

Gertrude Wickramasinghe

The Wickramasinghe’s younger daughter Gertrude Mildred, born in Gorakana on 29 May 1905, was educated at the leading girls’ school in Moratuwa, Princess of Wales’ College – the sister school of Prince of Wales’ College, Moratuwa. The schools served children of the prosperous merchants and their relatives from the Moratuwa-Panadura region. Although a Christian school, many pupils like Gertrude Wickramasinghe were from Buddhist families who were keen on educating their daughters.

Both schools had been endowed in 1876 by the famous businessman- cum-philanthropist, Charles de Soysa of Moratuwa who, in 1870, had given a banquet at his home in Colombo for two sons ofQueen Victoria who were visiting the island. Charles de Soysa was one of the richest men in the island, with wealth derived mainly from coconut, rubber and tea plantations – the original accumulation being by his father, Jeronis Soysa, in liquor retailing in the Central Province. Charles de Soysa’s wife, Lindamulage Catherine de Silva was an heiress – the daughter of Chevalier Jusey de Silva, another wealthy liquor merchant of Moratuwa.

When Gertrude Wickramasinghe joined the Princess of Wales’ College around 1911, the principal was Priscilla Marshall, a Sri Lankan Eurasian who held this post from 1909 to 1938. She was a graduate of Madras University and was keen to promote female education, encouraging pupils of the school to sit for the Cambridge Junior and Senior examinations, as well as introducing new subjects, including Science, Botany and Latin, into the curriculum. The Marshall family were educationists, and Priscilla Marshall’s sister, Ruth ran St. Clare’s School in Kollupitiya.

Princess of Wales’ College, started in the era of local capitalist expansion, was developed with the intention to promote female education and also cater to the demand by rich, educated men for wives with an English education. Like other Christian schools, Princess of Wales’ College not only aimed at providing educated Christian wives for Christian men of the same class, but also produced English-educated Buddhist women – as suitable wives for Buddhist men.

Girls’ Education

From the late 19th century onwards, Sri Lankan women had advanced in literacy, educational achievements and access to paid employment. It was an era when middle-class girls were encouraged by their parents to become ‘properly educated,’ thereby erasing any image of backwardness and illiteracy. Girls’ high schools on the British model attracted the attention of the new-rich and those aspiring to economic and social advancement. Colonial education in English for girls was academically oriented and geared to the Cambridge Junior and Senior examinations. In 1881, the first local girl took the Senior, and five sat for the Junior examinations. By 1900 the figures were 15 and 77, respectively. But girls’ schools also emphasized the ‘good wife and mother’ aspects of education – sewing, music, painting and other ‘ladylike’ accomplishments – the accepted hallmarks of the ‘respectable’ bourgeois woman. Some women sought further qualifications, and by the 1890s there were female doctors, nurses and teachers in Sri Lanka (Brohier, 1994).

By the early 20th century, there were many good schools for girls including the missionary schools. They included Bishop’s College, Methodist College, Holy Family Convent, Ladies’ College and St. Bridget’s Convent (all in Colombo), as well as Girls’ High School and Hillwood in Kandy, Vincent School in Batticaloa, Ferguson’s High School in Ratnapura, Southlands in Galle, Newstead School in Negombo, and Princess of Wales’ in Moratuwa. Although there were several Buddhist girls’ schools – Sanghamitta (Galle), Mahamaya (Kandy), Sri Sumangala (Panadura), as well as Ananda Balika, Musaeus College and Visakha Vidyalaya in Colombo – many Bud73 dhist parents, anxious for academic qualifications combined with strict discipline, continued to send their daughters to Christian missionary schools. Both NU’s father and Gertrude Wickramasinghe’s father were no exceptions. The increase in the number of schools geared to providing, from among their co-religionists, suitably educated wives for educated males benefited both the upper and middle classes. There was often a fusion of the old and new rich. Those ‘long on status and short on cash’ bought their way into families who were ‘long on cash and short on status.’ An educated daughter was also an asset. Neloufer de Mel has noted that, among the “ingredients that comprised Sri Lanka bourgeois respectability” was an education in English for girls, which “had to be modern, i.e. Western-oriented.”

Clearly there was value placed on an English education, a knowledge of modern subjects and qualities of discipline and industry instilled by the missionaries that would make their daughters not only good wives but also assets to their husbands. (de Mel, 2001, pp.106-7)

NU, who no doubt preferred to have a wife with an English-medium education, was thus keen on marriage to Gertrude, in spite of the opposition to the marriage in sections of the Wickramasinghe family, especially Gertrude’s brother-in-law and sister. But Gertrude was defiant and insisted on the marriage. Finally, several years after they had first met, the wedding took place in 1929 at the Wickramasinghe home, in Gorakana, Moratuwa. NU, who was 21 years of age, received a cash dowry of Rs. 10,000 and a 25-acre rubber estate in Avissawella. Norman Wickramasinghe found a house for the couple in Lunava, a fashionable suburb of Moratuwa, for which he paid the rent, and also gave his daughter an allowance equal to NU’s monthly salary at that time, which was Rs. 112 (de Zoysa manuscript, p.7). To NU, the money, the rubber estate and house were tremendous incentives, giving him the economic security to further his driving ambition to study. He worked hard at his job, continued to give tuition, and most of all, never gave up studying to improve his own position in life, and perhaps to prove to the Wickramasinghes that he could succeed.

(N.U. JAYAWARDENA The First Five Decades Chapter 5 can read online on https://island.lk/early-employment-and-the-move-to-colombo/

(Excerpted from N.U. JAYAWARDENA The first five decades)

By Kumari Jayawardena and Jennifer Moragoda ✍️

Features

Trump’s Delinquent War Game: No Early End in Sight

It is fruitless analyzing US President Trump’s reasons for going to war with Iran or the conflicting outcomes he says he is looking to have in the end. It is quite possible that he may have made the decision to attack Iran after being cajoled by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. It is a good time to attack because Iran is at its weakest moment yet posing an imminent threat warranting a pre-emptive attack. Strange and circular reasoning is needed to justify unnecessary wars.

True to form, Trump did not consult any of his western allies the way his predecessors did in similar situations. He ignored NATO as much as he ignored the UN. Nor did Trump go through the internally established broad consultation and focused decision making processes that US presidents usually undertake before committing American forces abroad. The Congress, the institution under Article I of the American Constitution, was also habitually ignored .

It is likely that Trump secured tacit support from other Middle East governments, especially the Gulf states of Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, UAE and Oman that are Iran’s neighbours. The latter may seem to have been hoping to have it both ways – letting US and Israel take out Iran’s reprehensible regime while appearing to stay neutral in the fight. That calculation or miscalculation explosively backfired when Iran started firing drones and missiles not only into Israel but practically into every Arabian (Persian) Gulf country, hitting not only American bases but also civilian centres. The welcoming reputation of the Gulf countries as secure oases for foreign investment, tourism, sports and entertainment has been seriously shattered.

Escalating War

In addition to the six Gulf states, Iranian missiles have reached Iraq, Jordan and far away Cyprus. Even Turkey and Azerbaijan have been targeted. Israel has been hit and has suffered casualties far more in the few days of fighting than it has in all the past aerial skirmishes. The US outposts are under attack as well. The Embassy in Kuwait was hit on Monday. The next day two drones fell on the US Embassy in Riyad, Saudi Arbia, apparently the most fortified American outpost abroad. This was followed by drone attacks on the US Consulate in Dubai and on the American military base in Qatar, the largest in the region. Six American servicemen have been killed and 18 injured in the first four days of the war.

The Trump Administration that has been notorious for picking countries to deny US visas, is now asking Americans to return home from 14 Middle East countries for the sake of their own safety. Washington has closed its embassies in Riyadh and in Kuwait and has ordered non-emergency staff and families to depart from its other embassies in the region. But leaving the embattled region is not easy with flights cancelled and air space closed. Belatedly, the State Department is scrambling to make arrangements to help stranded Americans find their way out by air or by land to neighbouring countries. It is the same story with governments of other countries whose citizens are living and working in large numbers in the Middle East. The monarchs of Middle East depend on migrants of many hues to do their blue collar and white collar labour while keeping their citizens in cocoons of comfort. That equilibrium is now under threat.

Iran’s losses are of course significantly higher, already hit by over 2,000 Israeli and US missiles reaching multiple targets in 26 of Iran’s 31 provinces. Over a thousand people have been killed including 180 students in a girls’ school in the south. Buildings and infrastructure and installations are being devastated. Israel has opened a full second front in Lebanon using the thoughtless Hezbollah’s aerial provocation as excuse for once again badgering Beirut and its suburbs. A week into the war there is no early end in sight. Only escalation.

Not only Iran but even the US is extending the waves of war. A US submarine torpedoed without warning and sank the IRIS Dena, a Moudge-class Iranian frigate, in the Indian Ocean not far from Galle. The frigate had about 130 sailors on board and was sailing home after participating in the International Fleet Review (IFR) and multilateral exercise, MILAN-2026, organized by the Indian Navy at Visakhapatnam. The frigate was reportedly not carrying weapons in keeping with the protocol for international naval exercises. Also, according to reports, Americans were in the know of the Fleet Review in India and its participants. Yet the US Secretary of War, Pete Hegseth, went on public television to say: “An American submarine sunk an Iranian warship that thought it was safe in international waters,. Instead, it was sunk by a torpedo. Quiet death.” How tragically surreal!

It fell to little Sri Lanka to respond to the distress call of the sinking sailors. Sri Lanka’s navy and emergency services have done an admirable job in fulfilling their humanitarian responsibilities. The Sri Lankan government has also handled a difficult situation, complicated by a second Iranian ship, with poise and purpose. On the other hand, unless I missed it, I have not seen any official reaction by the Indian government to the reckless sinking of one of its guest ships. An opposition parliamentarian of the Congress Party, Pawan Khera, has been cited as asking on X, “Does India have no influence left in its own neighbourhood? Or has that space also been quietly ceded to Washington and Tel Aviv?”

India is not the only one that has ceded space and time to the bullying whims of Donald Trump. With the exception of Spain, the entire West is literally genuflecting for fear of getting hit by tariffs. Notwithstanding the US Supreme Court ruling much of Trump’s tariffs to be illegal, and a Federal Court now ordering that the collected monies should be paid back to those who had paid them. The situation is a far cry from the European reaction and the public lampooning of Bush and Blair when they went to war in Iraq two decades ago.

The Missile Math

Two factors may objectively determine the course and the duration of Trump’s war: weapons stockpiles and the oil and natural gas markets. Higher prices of oil and natural gas will increase domestic pressure on Washington to find an offramp to the war sooner than later. Other countries may have to suffer not only higher prices but also shortages of fuel. The weapons are a different matter.

The ongoing aerial warfare involves the use of drones and missiles to attack as well using defensive missiles to detect and destroy incoming projectiles before they hit their targets. After the beating it took last year and this week, Iran has no missile defense system to speak of, but it has both a stockpile of drones and missiles and capacity for rapidly producing them. The military question is whether Iran’s stockpile of offensive drones and missiles can outlast the combined defensive missile stockpile of the US, Israel and the Middle Eastern countries. There is no clear answer, only speculations about Iran and US concerns over its own stockpile.

The “troubling missile math,” as it has been called is underscored by the concern expressed by US Secretary of State Marco Rubio, that Iran has the capacity for “producing, by some estimates, over 100 of these missiles a month. Compare that to the six or seven interceptors that can be built a month.” The worry is also about the depleting impact that the extended use of interceptors against Iran will have on American stockpiles elsewhere in the world, especially in areas involving China. That is part of the standard military calculation. What is bizarre now is that after starting the war on a whim last Saturday, Trump is convening a meeting within a week on Friday with weapon manufacturers to urge them to produce more.

Secretary Rubio also added that destroying Iran’s missile capacity is the goal of the US campaign. Iran’s missile capacity involves different missiles with different flight ranges. The shorter the range the larger the stock. Iran does not have the standard two-way intercontinental ballistic missile, and it is nowhere near developing them. The current Administration has recklessly claimed that Iran is capable of launching missiles to hit America and has unfairly named and blamed all previous presidents for not doing anything about it.

Trump’s predecessors were fully aware of America’s unmatched military superiority and Iran’s utter limitations. They were also aware that going to war with Iran to destroy its drones and limited range missiles will create more problems without solving any. The Obama Administration in consort with China, UK, France, Germany and Russia produced the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) committing Iran to have nuclear programs for peaceful uses only. Trump tore up the Obama plan and instead of using the opportunity this year to create a new and stronger program, chose to start a war instead.

As things are, unless the US-Israel axis succeeds in literally obliterating all drones and missile production resources in Iran, Iran will retain the capacity to produce drones and short-range missiles with which it could torment its neighbours for long after Trump and Netanyahu declare the war to be over. It may never be a long-range menace – in fact, it never was – but it could become an even greater short-range nuisance.

The US is no longer indicating a time limit for the war to end. For Netanyahu, it is not going to be an endless war. Of the two, Israel might be having some clear objectives to be achieved before ending the war. For Trump and his Administration, on the other hand, the objectives of the war are chaotically evolving on a daily basis, and the world will have to wait till the man of the deal finds some outcome or outcomes that can be shown as success and call it quits.

Regime Change: Insult after Injury

Iran’s Supreme Leader and forty or so other top Iranian leaders were taken out in the first minute of the fight by “pinpoint bombing”, as Trump boasted in his auto-poetic truth social post. But the Iranian regime has not collapsed. It has shown remarkable structure and durability despite the death of its Supreme Leader. It is America that is showing its inability to contain its Supreme Leader from going berserk on the world through tariff and bombing terror – in spite of all the checks and balances that Americans thought they have constitutionally practised and honed over 250 years. It is also poetic comeuppance for the Iranian regime that, after 47 years, it should now face its undoing by an unhinged American hegemon for theocratically subverting the 1979 revolution from realizing any of its secular possibilities.

Trump now wants to add insult to injury by forcing himself into the succession process for selecting a successor to Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Iran has a well-established succession process, almost akin to the conclave in the Vatican, in which a body of 88 elder clerics, the Assembly of Experts, are convened to elect through a secret vote the new Supreme Leader. Over the last few days, it has been widely reported that the late Khamenei’s 56 year old son Mojtaba Khamenei has emerged as the leading candidate to succeed his father as the next Supreme Leader. His political strength and leadership claim are reportedly based on his close connections to the powerful Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

Mojtaba is said to have been the shadow Supreme Leader in recent years making decisions in place of his ageing father. For that reason, he is reviled by Iranians who are opposed to the regime and who have been oppressed by the regime. There are also allegations and rumours about his amassing wealth and investing in properties and opening bank accounts in London and Geneva. At the same time, there could also be sympathy for him in the ruling circles because it was not only his father and his mother who were killed in the first minute bombing but also his wife and his son. While ideologically he has been a hawk, Mojtaba is also described as a “pragmatist.” Being pragmatic in the current context, according an unnamed Tehran academic, would imply that Mojtaba Khamenei will be seeking revenge for the US-Israeli attacks on his family and his country – not through victory in war but by ensuring “the survival of the Islamic Republic.”

President Trump is not bothered about the dynamics and nuances of Iranian leadership politics and has no hesitation in inserting himself into the succession process. In an interview with the American news website Axios, Trump has declared that he wants to be personally involved in the Iranian succession process, and that the selection of the younger Khamenei would be “unacceptable” to him, because “Khamenei’s son is a lightweight.” “I have to be involved in the appointment, like with Delcy [Rodríguez] in Venezuela,” Trump went on, because “we want someone that will bring harmony and peace to Iran.”

Comparing Venezuela and Iran is no less preposterous than the Bush Administration’s decision to invade Iraq in addition to Afghanistan in order to punish Al Quaeda for 9/11. Trump now appears to be seeking not a wholesale regime change but a retail leadership change in the old regime. This is only the latest addition to his lengthening wish list for the war with no method or plan to achieve any of them. Add to the growing list the news that the CIA is putting together a Kurdish insurgent force to foment “a popular uprising” within Iran.

That would be back to the future and the return of the CIA, but in a totally different situation from what it was 73 years ago when the CIA, in partnership with Britain’s MI6, staged the 1953 coup that ousted the government of then Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh and reinforced the monarchical rule of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the Shah of Iran. The purported plan now is to arm and organize Kurdish forces in Iran and Iraq to engage the Iranian security forces and thereby to create internal spaces for Iranian civilians to come out to the streets and take over their country. Those who are entertaining this plan are also aware of its inherent dangers and cross-border and pan-ethnic implications for Iraq and even Turkey and Syria. Trump is reportedly aware of the plan but may not be bothered about its unintended consequences.

by Rajan Philips

Features

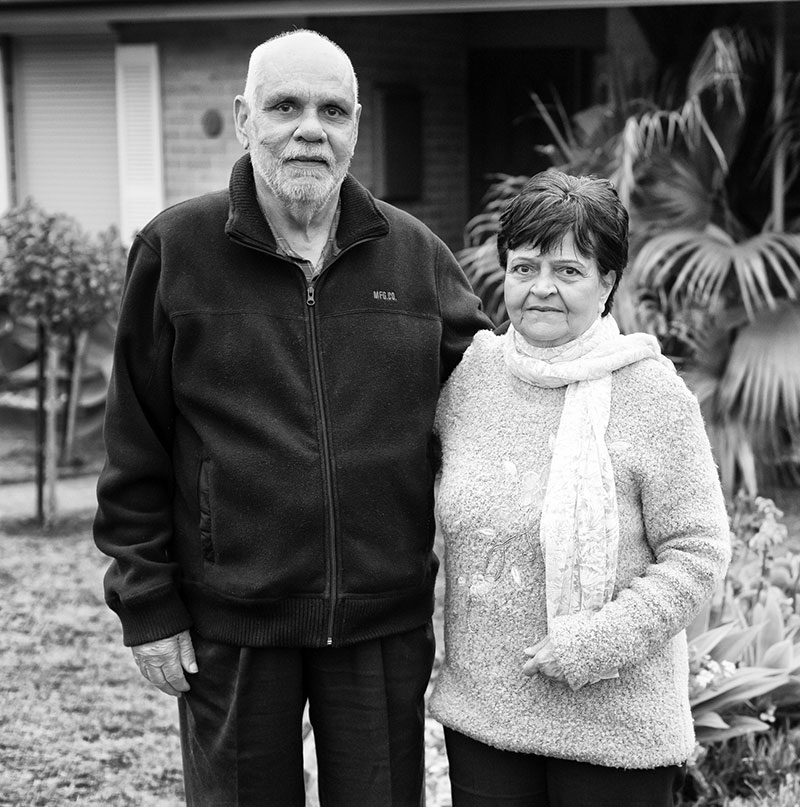

ARRIVING DOWN UNDER

We (my wife Esther, two children, Frances (two yrs six months) and Richard (six months), and myself left Katunayake airport for Australia at 4.30 pm on March 12, 1968, flying UTA French airlines.

The final day in Sri Lanka was quite a busy one, receiving our foreign exchange allocation only at 11.00 am that morning, then rushing back home for the trip to the airport. Having long worked as an engine driver for the CGR, it was my intention that our final trip in then Ceylon would be by train; as such we took the 12.45 pm train from Maradana and detrained at Katunayake station.

I had pre-arranged with the Station Master at Katunayake to have a fleet of taxis stand by to convey us (friends, relatives and ourselves) to the airport. The plane departed on schedule and from the moment it took off I was air sick all the way.

At Singapore there was a break of a few hours and I managed to get off into the transit lounge for a breath of fresh air which seemed to revive me. Esther and the children however, stayed on board the aircraft. Once the plane took off, I was again a victim to air sickness. Fortunately the seats behind had fallen vacant and I was able to bed down for the night. It was Esther who had a torrid journey, minding the two kids all the way.

I was woken up whilst the plane was flying over Central Australia and did see the morning glow light up the land. We arrived at Sydney in the morning and I was amused to see that as soon as the plane landed a man entered the plane carrying an aerosol can, the contents of which he sprayed around the interior of the plane. He was, I am told, the Quarantine Officer, carrying out his duties to ensure no ‘nasties’ entered the country.

Before we disembarked a pleasant surprise awaited us – a telegram from a pen friend of mine in Queensland welcoming us to Australia, was delivered to us. We had a two hour break at Sydney Airport before we caught our connecting flight to Melbourne (Essendon Airport).

It was a hot sunny day, the children were tired and grumpy and I called over at a food outlet to buy some drinks. All I had with me was a British pound sterling note. I gave them that and was given the change in Australian currency, which I had never seen before. I kept looking at it for a while, when the lady at the counter wanted to know what was wrong.

I told her I was migrating to Australia with my family and had never seen Australian currency before and was looking at it. She said, ‘please give it all back to me’, which I did. She then gave me back the pound note and said, “Welcome to Australia. I came here from Poland 10 years ago, I hope you settle in happily”. An auspicious start indeed to our life ‘Down Under’.

The family (my parents, brothers and sisters) were all gathered to meet us as I was the last member to migrate. The drive home was fascinating to say the least, the roads, bridges, lack of people on the roads, quiet traffic (with no cacophony of horns) made it all the more pleasant.

We were seeing television for the first time, and I thought to myself, how wonderful to ‘see the cinema come home’ as the day unfolded and we began to discover more delightful Australian customs and way of life. The following day, accompanied by a brother, I visited the local factories and businesses – Yakka, Ericsson’s, Nabisco Biscuits, Ford Motor Company – in search of employment.

I was flabbergasted to hear each one of them say I was too qualified for them and as such they could not employ me. This was indeed a new one for me. My brother explained, that they knew I was a new migrant and was looking for any type of employment to get settled, and then later on would obtain better employment commensurate with my qualifications. Thus all their training would have been in vain, not to mention the costs involved.

The following day I went to the City, accompanied by another brother. The train journey there and back, the ‘big smoke’ had me enthralled. We called at the recruitment office for both the Federal and State Public Services where forms were filled in and an application for employment lodged. Both agencies stated that it would be some months before I heard from them.

We next called in at the Australia Post recruitment centre as they were recruiting mail sorting officers and signed up with them to begin work the following Monday. The three months at the Postal Training School was interesting; one had to familiarize oneself with the various postal towns in districts and learn speed sorting. At the end of the three months I was given a bundle of 25 letters and had to sort it in a minute into postal districts, with only three errors allowed.

I was smart enough to work on the names in districts, in line with railway stations in various areas of the CGR – Matara, Badulla, Trinco, Batticaloa, KKS lines, thus being able to acquaint myself with the names quicker, and in the final test had only two mistakes.

As son as I had passed out from Postal School, I had a letter from the State Public Service offering me a clerical position (the choice was mine) at any of the following – the Department of Agriculture, Department of Health, Motor Registration Board, Grain Elevators Board and Fisheries & Wildlife Department. The last seemed very interesting and I picked it.

The postal authorities were unhappy to say the least when I resigned my position immediately after three months training (I now understood why I was earlier told that I was too qualified for employment). And so began a 25 year carrier with the State Public Service, which saw me serve in the same ministry, but various divisions – Fisheries & Wildlife, Conservation, Environment Protection Authority, Conservation & Natural Resources, Forest Commission, National Parks and Conservation & Environment.

Due to needs of supplementing my income, I obtained part time employment as an office cleaner with Brown’s Office Cleaning Services and worked for them for 15 years. They had contracts for cleaning offices in the City of Melbourne. A number of Sri Lankan immigrants worked for them supplementing their income. Thus began an extra stint of duty, leaving one’s day job, which ended t 4.30 pm.

Whilst the work was not too arduous the long hours were very demanding. I worked three hours each weekday evening, beginning at 5.00pm. By the time I reached home on public transport, it was well past 9.00pm and I was completely exhausted, especially during the summer months. Fortunately although it was part time work, I was also entitled to sick leave and annual leave.

Esther always wanted to remain at home and look after the kids. This was indeed a most demanding role for her, in that at one time we had the five kids attend five different Catholic schools in the area, which were graded senior, junior, high school (college) and then also segregated between boys and girls. She spent some 15 years driving them to the various schools and back.

One of the first things my father got me to do on arrival in Australia, was to fill in an application form with the Housing Commission of Victoria for a home of our own. This they told us would take anything up to three years before we were allocated one.

After an initial stay of four months with my parents at Broadmeadows, we decided to look for our own accommodation (a flat or house), but found that no one was keen to rent houses to people with children or pets. Finally we were able to locate a large flat (over a small shopping centre) in East Thornbury, where my parents lived when they moved to Australia.

The Estate Agent amazed me when I told them we had children saying, “we love children, yours are welcome.” When I said I had no Australian references, which everyone wanted, they said “If you were good enough for the Australian Government, you are good enough for us”. They were truly amazing and people with a heart.

We lived at East Thornbury for three years before we were given a choice of selecting a house from one of six being built at Broadmeadows West. This we did and this has been our home for the past 38 years. Initially it was difficult as it was a new area, with no street lighting and away from most shopping amenities, but over the years much development has taken place in and around the area.

At the early stages, we had most services delivered to the door – bread, milk, dry cleaning, fruit & vegetables, newspapers, the onion & potato man, mail etc. Over the years the services have dwindled (with progress) and today only the mail and newspapers are delivered.

After 25 years service with the State Public Service, I took the opportunity of ‘early retirement’ being offered by the public service and retired in April 1993.

by Victor Melder

Features

How Helmut Kohl braved the tsunami, P-TOMs and Kadirgamar assassination

This is the place to introduce the episode of ex-Chancellor Helmut Kohl of Germany. “This legendary unifier of post war Germany was at a small hotel in Hikkaduwa undergoing Ayurveda treatment when the Tsunami struck. A German Minister who owned a house in Hikkaduwa and visited Lanka regularly had recommended Ayurveda treatment to The Chancellor and head of her party- the Christian Democrats.

The German Embassy was at its wits end because Kohl had disappeared without a trace. They contacted us and we activated our Grama Sevaka network to find that Kohl had been taken to the safety of his home by a hotel employee. When we offered to send a helicopter to bring him to Colombo the Chancellor had replied that it was not necessary as he was well looked after by his host. He came by car the following day in order to thank CBK for her help.

I went to President’s House with Kohl who seemed quite relaxed in his coloured shirt, crumpled pants, a grey seersucker coat and rough boots. He was full of praise for the Sri Lankan people who had helped him and all the tourists in distress due to the Tsunami. Kohl said that he wanted to help in the rehabilitation of the south in his personal capacity. When he got back to Germany he set up a group of rich friends called “Friends of Helmut Kohl” who sent money to build a hospital in Mahamodera, Galle.

The money was lodged in the German Embassy. But the usually lethargic Health department dragged its feet on the construction work on the guise that the money was not sufficient for their grandiose hospital plans ignoring the value of the superb gesture by Kohl. Unfortunately he died before the completion of the project and therefore could not keep his pledge to come to Galle for its opening.

Later in time I was a member of a Parliamentary delegation led by Speaker Karu Jayasuriya which included Sampanthan, Rauf Hakeem, Anura Dissanayake and several others. I suggested to our group that we pay a belated tribute to Helmut Kohl who had died a few months previously. This was immediately welcomed by the parliamentarians and the organizers of the tour and we jointly paid our heartfelt tribute to a great friend of Sri Lanka who was an eye witness to the success of our rehabilitation effort.

Post Tsunami Operational Management Structure (P-TOMS)

The Tsunami was particularly harsh on the eastern and northern coastline because it was directly in the way of the giant waves created in Indonesia and deflected to our shores. It also created a transformation of the political scene and the nature of the war. The LTTE had invested considerable resources in building up its “Sea Tigers”. They wanted control of the northern seas in order to increase their supply of weapons and ammunition. The Sea Tigers established a presence in east Thailand so that arms could be purchased from Cambodia, Vietnam and Thailand. The fighting in the Indo-China theatre was over and the cut rate weapons market was flourishing.

Our embassy in Bangkok had an army officer who was monitoring terrorist activities but he was helpless because Thai officials in the lower echelons were in the pay of the LTTE. In addition to that problem, the mediocre officials of our Foreign Ministry were no match for the determined LTTEers one of whom had married an influential Thai lady. With money coming in from expatriates they had even set up a shipping line which was so well run that they could finance weapons buying for the LTTE with its profits.

We had received intelligence that the LTTE was preparing for a major “Sea Tiger” operation from their base in Mullaitivu. This base area concept shows the advanced thinking of the LTTE which was attempting – then unsuccessfully – to even manufacture a low cost submarine. Fortunately for us the Tsunami wiped out the base of the “Sea Tigers” together with many of their assets such as boats, proto-type submarines and diving gear.

True to form they sent signals for talks which they had earlier broken. Their diaspora had mounted a campaign to collect funds for rehabilitation. At this stage the UN got into the act and with the World Bank and IMF persuaded the CBK government to consider a power sharing arrangement principally for the rehabilitation of the North and East. It was to be called P-TOMS. CBK appointed Jayantha Dhanapala as the head of SCOPP – a secretariat to coordinate the relief effort in the North and East. The World Bank appointed Peter Harrold, its representative in Colombo, to coordinate the P-TOMS effort with SCOPP.

Estimates were made by SCOPP regarding the amount necessary for the rehabilitation of the North and East. This budget became the talking point of several successive regimes who promised to allocate such funds in exchange for Tamil votes in the North. Mahinda Rajapaksa’s agents held this figure as a bait to promote a boycott of the Presidential poll in 2005 which threw the election which was in Ranil’s pocket to MR thereby changing the destiny of the LTTE as well of the country. [MR cleared the 50 percent hurdle by only 25,000 votes].

Perhaps to strengthen the push for P-TOMS, Kofi Annan the Secretary General of the UN arrived with a large contingent of staffers and I was asked to meet and greet him in Katunayake. We gave Annan a grand welcome but he seemed distracted and was only interested in getting his Swedish wife who was hanging back, into the spotlight. CBK had several discussions with him but we ran into a snag in that he wanted to visit the North and meet Prabhakaran.

Perhaps some of the big powers had got to him as he was in the midst of a scandal about his son from his first marriage who was facing charges of corruption. The scandal was rocking UN headquarters. Annan who was elevated from his earlier status as a UN functionary to satisfy African members, was according to several biographers, indebted to the west and could not end his tenure to the satisfaction of the majority of the UN membership.

CBK, already under pressure for mishandling the P-TOMS campaign, was adamant that Annan should not meet the LTTE which would have given the terrorists parity of status with the SL state. Since such an interpretation was circulated by virtually all political parties in the South she was pushed to a very difficult position. After much discussion Annan settled for a helicopter tour of the North. I found that he was a weak leader who was led by his nose by Mark Mallock Brown – his chief of staff, who had been in charge of UN operations even during its disastrous forays in the Congo.

Mallock Brown was later identified as a camp follower of the West who compromised the credibility of the UN. I have memories of Mallock Brown holding forth on their next step here while Annan and Dhanapala were mere passive listeners. This Western initiative of P-TOMS did not finally see the light of day. But it split the ruling coalition of the PA and JVP irrevocably and Mahinda Rajapaksa burnished his credentials as an opponent of the project. He became popular with the PA and its allied parties over and above CBK.

When the P-TOMS project was to be placed before Parliament Mahinda as Prime Minister refused to present it on the floor of the House. CBK was too weak to dismiss him partly because Lakshman Kadirgamar also was a strong opponent of P-TOMS. Instead she got Maithripala Sirisena to present the proposal. But the Opposition which was joined by the JVP including its functioning Ministers, took to the streets. The JVP members demonstrated and disturbed the proceedings from the well of the House and then resigned “en masse” from the government putting its majority in jeopardy. Mahinda’s anti-P-TOMS stand endeared him to the JVP, which had earlier preferred Kadirgamar to him, and helped him to garner votes which went a long way in ensuring his ultimate victory. He had become so powerful that CBK had no option but to accommodate him.

Assassination of Lakshman Kadirgamar

Another blow was struck at CBK and the government by the I TTE when they assassinated Lakshman Kadirgamar near the swimming pool of his house. He had a successful kidney transplant in India – with a Buddhist monk from Balangoda donating a kidney – and was asked to swim regularly as exercise by his doctors. I knew of this arrangement because when we travelled together he always asked the Foreign Office to put him tip in a hotel with a heated swimming pool.

He was about to enter the water in the swimming pool when a LTTE sniper shot him through a window in a neighbourhood flat. This dastardly crime wits condemned unanimously by the international community. India sent her Foreign Minister to attend the funeral. Ksdirgamar’s death brought CBK’s Government to the brink of collapse. The JVP though leaving the Government respected LK and paid a tribute to him by arranging for their leaders to follow his hearse on foot to Kanatte.

It must be mentioned here that LK nearly pipped Mahinda for the post of PM in 2004. He had the backing of the JVP who wanted CBK to appoint LK and in the alternative appoint Maithripala Sirisena as PM. He was also supported by India but CBK was afraid that Mahinda will break up the party if he was deprived of the Premiership. After LK’s demise she undertook a mini reshuffle and Anura Bandaranaike had his ambition of being Foreign Minister realized.

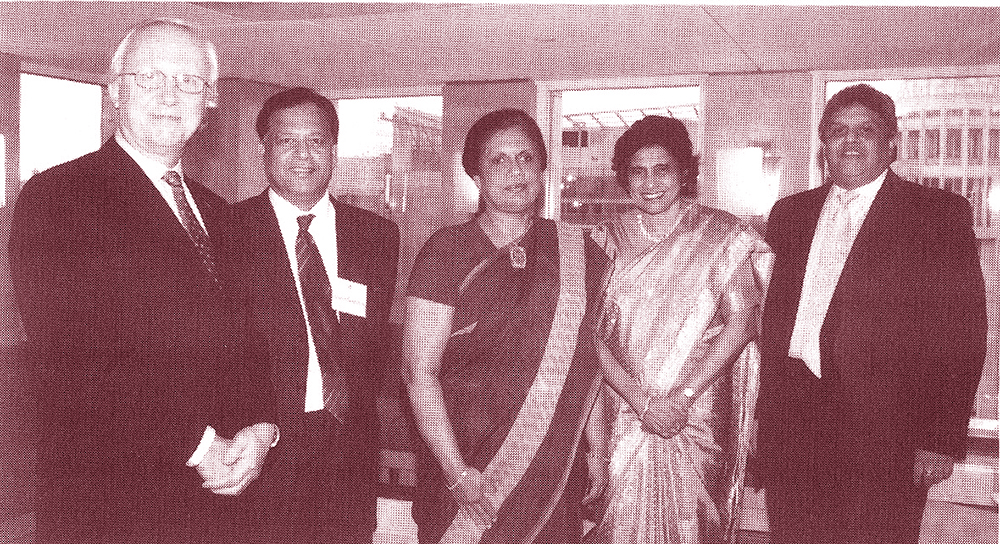

To succeed him as Minister of Industries and Foreign Investment she appointed me in addition to my portfolio of Minister of Finance. Arjuna Ranatunga was the Deputy Minister of Industries and I left most of the administrative work to him. When we had an investment promotion meeting in Delhi I invited Arjuna and Aravinda de Silva to be our delegates and they stole the show among the cricket mad Indian investors. All the tables at dinners hosted by us were taken and we had many friends appealing to us to get them reservations even at the last minute.

We had such good relations that I was invited to take part in popular TV talk shows. I remember that Shekhar Gupta invited me for a discussion on our health services with Kajol – the top Hindi film actress who was brand ambassador for Narendra Modis “clean Bharat” campaign. She was a charming young lady who recounted her enjoyable stay in Sri Lanka when she accompanied her mother Tanuja who was shooting a film in Colombo with Vijaya Kumaratunga as her co-star.

After LKs murder the fear of the LTTE was so strong that CBK could not even attend the funeral ceremony. PM Mahinda Rajapaksa represented her. This death was a bitter blow to me because as an old Trinitian friend he would always consult me on party matters. I still have a letter he wrote to me about a coffee t able book on the art of Stanley Kirinde which he sponsored in honour of our mutual college friend.

(This book is available at the Vijitha Yapa bookshops)

(Excerpted from vol. 3 of the Sarath Amunugama autobiography)

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoBrilliant Navy officer no more

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoUniversity of Wolverhampton confirms Ranil was officially invited

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoSri Lanka – world’s worst facilities for cricket fans

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoLegal experts decry move to demolish STC dining hall

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoA life in colour and song: Rajika Gamage’s new bird guide captures Sri Lanka’s avian soul

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoFemale lawyer given 12 years RI for preparing forged deeds for Borella land

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoCabinet nod for the removal of Cess tax imposed on imported good

-

News1 day ago

News1 day agoWife raises alarm over Sallay’s detention under PTA