Opinion

Four generations

Surasena was a scraggy boy with a runny nose, most of the time. He came to school sometimes, when he was well enough. Coughs and colds were a part of him. The entire school had an enrolment of less than 100; attendance varied from about 80 to about 100. Enrolment fell as students dropped out as they grew older: in grade V, there were usually 6 or 7 students, mostly boys. Most students were in Kindergarten, the Lower and the Upper. There were six teachers, one female, who was the principal’s wife, and both came from about 75 km away. They lived in the principal’s quarters with no other suitable house they could rent in the village. There was one English teacher, a man who cycled daily from a considerable distance. He was remarkably regular. He was the class teacher for Grade III and taught English in grades III, IV and V. He had had no special training in teaching English, or any other language and his final year students could hardly write the English alphabet without error. The parents of the children were mostly illiterate and hardly came to school after they had brought their child for admission. Surasena’s illiterate parents saw no function they could serve in the school. Teachers did the teaching.

Although Surasena was irregular in attendance, he picked up what was taught in class without any effort. When the end-of-term tests came, if he were present, he always came first in class. One teacher noticed this and spoke to the principal. The teacher thought that the boy was bright enough to win a scholarship if the gaps in his knowledge of arithmetic could be filled. Because the boy had come to school only when he was well, there were large gaps in his competence, especially in arithmetic. The young teacher took up the challenge, and when the results came, the boy had done well. So began a venture, which few had set out on then. One scholarship after another carried him to the highest centre of learning in his discipline, where he earned the highest degree any university could award.

Then a career: compromising among several objectives and laying aside many objections, Surasena decided to work for the world’s primary intergovernmental organisation. In doing so, he chose to live in the richest city in the world. Rich cities offer citizens many and varied services unavailable in less sophisticated habitats: theatres, concert halls, public libraries, high quality schools, universities, good sanitation and sophisticated architecture. Surasena chose to send their children to a unique school where both students and teachers came from many parts of the world. When the children prepared to go to university, each of them found her/himself in the first percentile of intellectual ability. Each chose to attend the highest quality colleges and universities. Their first jobs were with the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Federal Reserve System, both the highest-level regulatory agencies in that country. They eventually changed their careers and residences. One took up to law in New York City and the other a professorship in a state university.

Two young men in the fourth generation have completed secondary school and are in universities studying engineering.

An illiterate family goes to university. A family that lived in a coconut leaf thatched hut in a remote village lives in good housing in choice parts of cities, large and small. A boy who had only rice ration books in his home dispersed his collection of nearly one thousand books to several universities. A man who had never seen a play on a stage goes to Broadway and Carnegie Hall regularly. A young man in the fourth generation plays the saxophone at the Lincoln Centre. A family in the first generation that had not ventured beyond its native district, in the second generation, travels the world over. With different destinations and varied byways, these paths have been traversed by thousands of individuals and families in our society. A different and much larger cohort of our labour force, young, healthy and literate, has been pushed out of our economy.

I have used a fictional name to avoid embarrassing individuals. The rest of the narrative is factual. These sequences are repeated many thousands of times in this country, a highly mobile society. Neither poverty nor social position or habitat in town nor country bars children of ability from going where they wish. (One last habitat is systematically denied access to the high roads. One expects these roads to open literally and metaphorically, in short order.) We have had several employees in our household who used their earnings to pay for their children’s education at university. A few weeks back, one of those children graduated from a prestigious medical faculty in the country. A child in another family is in university studying mathematics. I reckon that is not an uncommon or infrequent occurrence.

It is one thing to move up the education ladder and another to find mobility within the economy. The space at the top is created in the economy and not in schools. It is an easy and common confusion to think that young men and women cannot find employment because they studied the wrong subjects at school or university. No matter what they learnt at school and university, they will be unemployed so long as there is no demand for labour. And the demand for labour is a function of the structure and the level of activity in the economy, not of the education system. Well into the second half of the 19th century, the founders of Dartmouth College declared, ‘though our great objective was to erect a seminary for educating ministers of the gospel, yet we hope that it will be a means of raising up men that will be useful in other learned professions- ornaments of the state as well as the church.’ And the United States was rushing to be the largest economy in the world. From 1929 to about 1936, there was high unemployment in most capitalist economies because economic activity fell disastrously and not because there was something suddenly wrong with education in those countries. Millions of rural folk in China and India, with no special education or training, marched to factories, when entrepreneurs opened workplaces for them. In both instances, the cause of unemployment is a lack of demand for labour. In China and India, demand arose when enterprises, both national and international, were created to produce goods and services. For markets in rich countries. Workers from Lanka took planes to workplaces overseas, where there was demand for them. Others remain unemployed in this country, because there are no enterprises that can pay competitive wages.

That brings us to the woeful inadequacy of interpleural activity in this country. The provision of health and sanitation and education in this country has been primarily the government’s responsibility. They have been resounding successes. Their success has had expected consequences on population changes. Our governments have systematically invested in peasant agriculture, placing populations from crowded areas in less densely populated areas. During the last 20 years or so, governments have invested, at exorbitant cost, in infrastructure development. The main visible enterprises in the private sector are in finance, construction and the manufacture of garments. Garment manufacturing is a low productivity activity (shoved out of high productivity economies), and there is severe competition for market shares. China (+Taiwan), Malaysia and India have employed millions of people in manufacturing high-wage products for markets in growing markets. To make matters worse, ground conditions in Lanka over a long period have been inimical to foreign enterprises. In the early 1960s, whatever foreign enterprises were inherited from colonial times were nationalized. Since then, the fate of attempts to establish foreign enterprises has not been bright. Every successive government, during the last few decades, has declared itself welcoming foreign investment. There were no takers. Foreign capital that came created disabling debt. In a society notoriously lacking entrepreneurial talent and overrun with corruption, debt inflows will create problems. We must grow enterprises (not wayside kade, which is a common sign of underemployment) and decide to create conditions that truly welcome foreign investment to provide full-time time well-paying jobs.

An education system by itself can do little to create employment, except in teaching.

by An Observer

Opinion

We do not want to be press-ganged

Reference ,the Indian High Commissioner’s recent comments ( The Island, 9th Jan. ) on strong India-Sri Lanka relationship and the assistance granted on recovering from the financial collapse of Sri Lanka and yet again for cyclone recovery., Sri Lankans should express their thanks to India for standing up as a friendly neighbour.

On the Defence Cooperation agreement, the Indian High Commissioner’s assertion was that there was nothing beyond that which had been included in the text. But, dear High Commissioner, we Sri Lankans have burnt our fingers when we signed agreements with the European nations who invaded our country; they took our leaders around the Mulberry bush and made our nation pay a very high price by controlling our destiny for hundreds of years. When the Opposition parties in the Parliament requested the Sri Lankan government to reveal the contents of the Defence agreements signed with India as per the prevalent common practice, the government’s strange response was that India did not want them disclosed.

Even the terms of the one-sided infamous Indo-Sri Lanka agreement, signed in 1987, were disclosed to the public.

Mr. High Commissioner, we are not satisfied with your reply as we are weak, economically, and unable to clearly understand your “India’s Neighbourhood First and Mahasagar policies” . We need the details of the defence agreements signed with our government, early.

RANJITH SOYSA

Opinion

When will we learn?

At every election—general or presidential—we do not truly vote, we simply outvote. We push out the incumbent and bring in another, whether recycled from the past or presented as “fresh.” The last time, we chose a newcomer who had spent years criticising others, conveniently ignoring the centuries of damage they inflicted during successive governments. Only now do we realise that governing is far more difficult than criticising.

There is a saying: “Even with elephants, you cannot bring back the wisdom that has passed.” But are we learning? Among our legislators, there have been individuals accused of murder, fraud, and countless illegal acts. True, the courts did not punish them—but are we so blind as to remain naive in the face of such allegations? These fraudsters and criminals, and any sane citizen living in this decade, cannot deny those realities.

Meanwhile, many of our compatriots abroad, living comfortably with their families, ignore these past crimes with blind devotion and campaign for different parties. For most of us, the wish during an election is not the welfare of the country, but simply to send our personal favourite to the council. The clearest example was the election of a teledrama actress—someone who did not even understand the Constitution—over experienced and honest politicians.

It is time to stop this bogus hero worship. Vote not for personalities, but for the country. Vote for integrity, for competence, and for the future we deserve.

Deshapriya Rajapaksha

Opinion

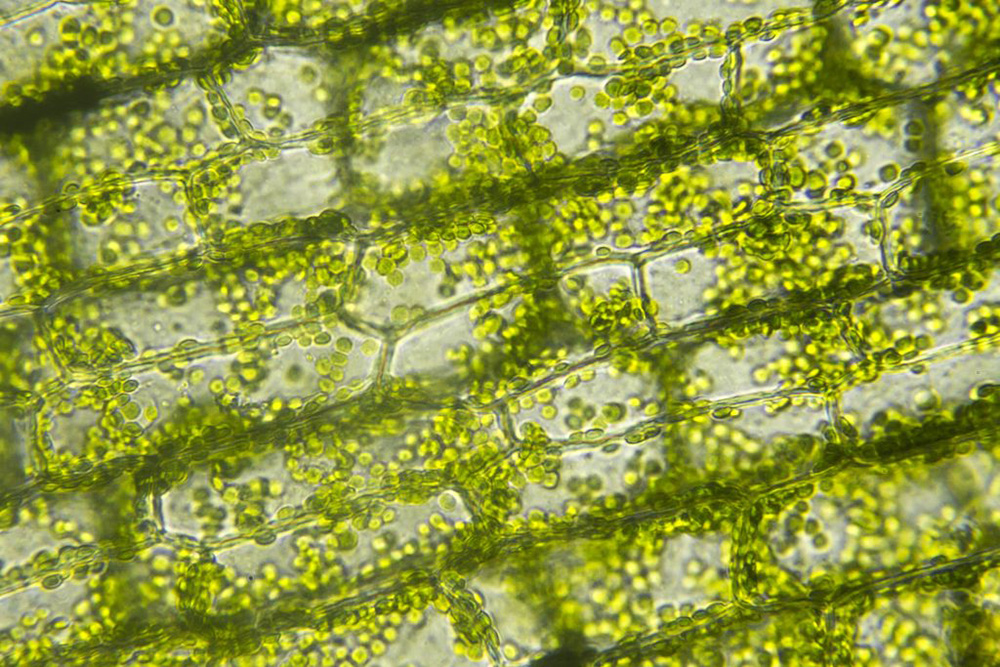

Chlorophyll –The Life-giver is in peril

Chlorophyll is the green pigment found in plants, algae, and cyanobacteria. It is essential for photosynthesis, the process by which light energy is converted into chemical energy to sustain life on Earth. As it is green it reflects Green of the sunlight spectrum and absorbs its Red and Blue ranges. The energy in these rays are used to produce carbohydrates utilising water and carbon dioxide and releasing oxygen in the process. Thus, it performs, in this reaction, three functions essential for life on earth; it produces food and oxygen and removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to maintain equilibrium in our environment. It is one of the wonders of nature that are in peril today. It is essential for life on earth, at least for the present, as there are no suitable alternatives. While chlorophyll can be produced in a lab, it cannot be produced using simple, everyday chemicals in a straightforward process. The total synthesis of chlorophyll is an extremely complex multi-step organic chemistry process that requires specialized knowledge, advanced laboratory equipment, and numerous complex intermediary compounds and catalysts.

Chlorophyll probably evolved inside bacteria in water and migrated to land with plants that preceded animals who also evolved in water. Plants had to come on land first to oxygenate the atmosphere and make it possible for animals to follow. There was very little oxygen in the ocean or on the surface before chlorophyll carrying bacteria and algae started photosynthesis. Now 70% of our atmospheric oxygen is produced by sea phytoplankton and algae, hence the importance of the sea as a source of oxygen.

Chemically, chlorophyll is a porphyrin compound with a central magnesium (Mg²⁺) ion. Factors that affect its production and function are light intensity, availability of nutrients, especially nitrogen and magnesium, water supply and temperature. Availability of nutrients and temperature could be adversely affected due to sea pollution and global warming respectively.

Temperature range for optimum chlorophyll function is 25 – 35 C depending on the types of plants. Plants in temperate climates are adopted to function at lower temperatures and those in tropical regions prefer higher temperatures. Chlorophyll in most plants work most efficiently at 30 C. At lower temperatures it could slow down and become dormant. At temperatures above 40 C chlorophyll enzymes begin to denature and protein complexes can be damaged. Photosynthesis would decline sharply at these high temperatures.

Global warming therefore could affect chlorophyll function and threaten its very existence. Already there is a qualitative as well as quantitative decline of chlorophyll particularly in the sea. The last decade has been the hottest ten years and 2024 the hottest year since recording had started. The ocean absorbs 90% of the excess heat that reaches the Earth due to the greenhouse effect. Global warming has caused sea surface temperatures to rise significantly, leading to record-breaking temperatures in recent years (like 2023-2024), a faster warming rate (four times faster than 40 years ago), and more frequent, intense marine heatwaves, disrupting marine life and weather patterns. The ocean’s surface is heating up much faster, about four times quicker than in the late 1980s, with the last decade being the warmest on record. 2023 and 2024 saw unprecedented high sea surface temperatures, with some periods exceeding previous records by large margins, potentially becoming the new normal.

Half of the global sea surface has gradually changed in colour indicating chlorophyll decline (Frankie Adkins, 2024, Z Hong, 2025). Sea is blue in colour due to the absorption of Red of the sunlight spectrum by water and reflecting Blue. When the green chlorophyll of the phytoplankton is decreased the sea becomes bluer. Researchers from MIT and Georgia Tech found these color changes are global, affecting over half the ocean’s surface in the last two decades, and are consistent with climate model predictions. Sea phytoplankton and algae produce more than 70% of the atmospheric oxygen, replenishing what is consumed by animals. Danger to the life of these animals including humans due to decline of sea chlorophyll is obvious. Unless this trend is reversed there would be irreparable damage and irreversible changes in the ecosystems that involve chlorophyll function as a vital component.

The balance 30% of oxygen is supplied mainly by terrestrial plants which are lost due mainly to human action, either by felling and clearing or due to global warming. Since 2000, approximately 100 million hectares of forest area was lost globally by 2018 due to permanent deforestation. More recent estimates from the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) indicate that an estimated 420 million hectares of forest have been lost through deforestation since 1990, with a net loss of approximately 4.7 million hectares per year between 2010 and 2020 (accounting for forest gains by reforestation). From 2001 to 2024, there had been a total of 520 million hectares of tree cover loss globally. This figure includes both temporary loss (e.g., due to fires or logging where forests regrow) and permanent deforestation. Roughly 37% of tree cover loss since 2000 was likely permanent deforestation, resulting in conversion to non-forest land uses such as agriculture, mining, or urban development. Tropical forests account for the vast majority (nearly 94%) of permanent deforestation, largely driven by agricultural expansion. Limiting warming to 1.5°C significantly reduces risks, but without strong action, widespread plant loss and biodiversity decline are projected, making climate change a dominant threat to nature, notes the World Economic Forum. Tropical trees are Earth’s climate regulators—they cool the planet, store massive amounts of carbon, control rainfall, and stabilize global climate systems. Losing them would make climate change faster, hotter, and harder to reverse.

Another vital function of chlorophyll is carbon fixing. Carbon fixation by plants is crucial because it converts atmospheric carbon dioxide into organic compounds, forming the base of the food web, providing energy/building blocks for life, regulating Earth’s climate by removing greenhouse gases, and driving the global carbon cycle, making life as we know it possible. Plants use carbon fixation (photosynthesis) to create their own food (sugars), providing energy and organic matter that sustains all other life forms. By absorbing vast amounts of CO2 (a greenhouse gas) from the atmosphere, plants help control its concentration, mitigating global warming. Chlorophyll drives the Carbon Cycle, it’s the primary natural mechanism for moving inorganic carbon into the biosphere, making it available for all living organisms.

In essence, carbon fixation turns the air we breathe out (carbon dioxide) into the food we eat and the air we breathe in (oxygen), sustaining ecosystems and regulating our planet’s climate.

While land plants store much more total carbon in their biomass, marine plants (like phytoplankton) and algae fix nearly the same amount of carbon annually as all terrestrial plants combined, making the ocean a massive and highly efficient carbon sink, especially coastal ecosystems that sequester carbon far faster than forests. Coastal marine plants (mangroves, salt marshes, seagrasses) are extremely efficient carbon sequesters, absorbing carbon at rates up to 50 times faster than terrestrial forests.

If Chlorophyll decline, which is mainly due to human action driven by uncontrolled greed, is not arrested as soon as possible life on Earth would not be possible.

(Some information was obtained from Wikipedia)

by N. A. de S. Amaratunga ✍️

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoSajith: Ashoka Chakra replaces Dharmachakra in Buddhism textbook

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoDialog and UnionPay International Join Forces to Elevate Sri Lanka’s Digital Payment Landscape

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoThe Paradox of Trump Power: Contested Authoritarian at Home, Uncontested Bully Abroad

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoSubject:Whatever happened to (my) three million dollars?

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoLevel I landslide early warnings issued to the Districts of Badulla, Kandy, Matale and Nuwara-Eliya extended

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoNational Communication Programme for Child Health Promotion (SBCC) has been launched. – PM

-

News3 days ago

News3 days ago65 withdrawn cases re-filed by Govt, PM tells Parliament

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoThe minstrel monk and Rafiki, the old mandrill in The Lion King – II