Features

Emotions, learning, and democracy: Reviving the spirit of education

When a father becomes a gambler and his obligation to his family takes the secondary place in his mind, he is no longer a man, but an automaton led by the power of greed.

(Tagore, Nationalism, 2018)

(Excerpts of the keynote address at Annual Sessions at the Faculty of Education, The Open University of Sri Lanka––Empowering Minds: Education for New Era.)

As I am coming from the Humanities and Social Sciences and Performance Studies disciplines, I have a close affinity with education and education philosophy. I have also been engaged in the current debate on higher education, writing and presenting my ideas with the academia and the public domains. I have been motivated by the like-minded scholars (Senanayake, 2021; Amarakeerthi, 2013; Uyangoda, 2017 & 2023; Rambukwella, 2024; Jayasinghe & Fernando 2023; & Jayasinghe 2024) who have been continually discussing problems related to our education and the role of humanities and aesthetics within this sphere. Some of the recurrent themes I have raised in these writings are burning issues in our current education scenario.

Among them, the indoctrination, decline of the arts and aesthetic education in our education sector, and the importance of creative arts in human development were prominent. Hence, in today’s speech, I will continue this discussion and try to broaden the scope of it. The theme of today’s speech can be categorized in three areas of studies: emotions, education, and democracy. What I am going to present today is the role of emotion in education and how this new paradigm of education could lead to the democratic establishments in society. In this speech, I try to build a connection between these key areas of arts and aesthetic education, its vital ingredient of empathy, and how this empathic education supports democracy in the society. This argument will be further elaborated in the course of my talk.

We, as a nation, are on the verge of a transition. This transition has been gradually taking place in our society through the influences of neo liberal economic and political changes happening throughout the region. The glory of our free education system and the heritage we envisioned have also been challenged by the new developments of private educational institutions. These new trends have distorted the true meanings while diminishing the philosophical and moral values of education.

It is the skill acquisition that has come to the fore of the educational discourse. Skills that can be used in the social milieu, and can support the economic growth of the country have been commissioned for our curricula. This mantra has been circulated and supported by the governments which ruled this country for decades. We, as academics, have also adopted strategies to cater these policies to indoctrinate our children to become future entrepreneurs. All the philosophical and moral values of education have been reduced to produce mere labourers. Education is interpreted as a commodity, which is being sold in the market based on supply and demand. We are advised that if we cannot compete in the market, our survival is at stake.

Now, who are we? And, where are we? Where is our society heading? These simple but vital questions are important for us to rethink how we educate our children and what we gain out of it. What kind of society we have created today, as a whole after implementing those educational policies imposed by the authorities? Over the past few years, the world has gone through a myriad obstacles and difficulties facing a worldwide pandemic and devastating wars. After many centuries, we faced the Covid-19 pandemic which challenged us on how we live as a community. Over two years, we were locked down and were isolated from the world. We were locked down in our own houses and the social distancing was imposed reframing ourselves to be connected with each other.

Pandemic, Aragalaya and emotions

Pandemic introduced different ways of learning and teaching in our education sector. The traditional ways of teaching and learning were replaced by the online modes of learning. We started conducting seminars and lectures through online zoom technology and other modes to connect with our students. Students, somehow or other, connected with us through their mobile phones and other devices. The conception behind all these technological advancements implied that the education can be successfully delivered via online mode, and the cost can also be reduced drastically allowing the government to reduce the cost of education and infrastructure.

However, the vital concepts in the educational business, such as corporeality, subjectivity, intersubjectivity, temporality, and spatiality have been redefined and challenged. The learning and teaching were redefined in the virtual reality, reducing the values of interpersonal and corporeal connections between learners. We tend to believe that it is not important for the learner to be present in front of other learners but is enough for her or his virtual avatar to be present.

Soon after the taming of the pandemic situation, our society was shattered with the economic bankruptcy and social upheavals. The financial hardship experienced by the people of the country, resulted in demand for basic needs, cooking gas, petrol, and other important rations. Vigil and silent protests, followed by the mass movements and occupation, ignited the country’s largest non-party people’s struggle, Aragalaya.

Youth of the country encamped the Galle Face Green, and established alternative communal spaces. Cinema, school, community kitchen and even an alternative people’s university were established. Within a few days, many GotaGoGama encampments were established in major cities of the country demanding the President and the Parliament to resign. The new people’s democracy was established by people, for people. This mass movement not only showed us new ways of governing the country but also new ways of living as a community. Human connection and communal living were established until the military actions uprooted the GotaGoGama encampment.

You must be wondering why I am trying to recall this unpleasant past of our social memory. Why is it important for us to go back and see how we passed this phase of time and have come to this point today? As my key ideas are related to emotional education, empathy, arts, and democracy, it is important for us to revisit such a brutal past and learn lessons from it. The pandemic situation taught us how it is important for us, as human beings, to be connected and live with each other as a society.

The pandemic taught us the importance of revisiting communal life, which has sustained and enriched our lives for centuries. Aragalaya further emphasised the importance of communal struggle and co-living in order for us to establish a democratic society. Democracy cannot be sustained without human engagement. It is not something that the ruling government or an alien authority donates to us. It is something that is generated through human connections and collective will. If we clearly scrutinise those two phenomena we experienced in the recent past, it is evident that in the first phenomenon, the pandemic challenged our emotional engagement with others. In the second phenomenon, Aragalaya, we witnessed how important emotions are to reconnect with people and demand for democracy.

Anxiety of our time

Today, as educators, we are on the verge of resolving complex issues related to education. Information technology and AI have invaded the traditional teaching and leaning approaches. The role of the teacher is being challenged and also being shifted by artificial intelligence. The question arises, whether we have a key role to play in the lecture theatre or in the classroom when AI invades our positions. With technological advancement and artificial intelligence, our role as teachers and also what we teach are being challenged. Now, the question is what educational philosophy or theory is suitable for us to guide our next generation of learners’ what methods are appropriate for this new generation to learn and become valuable citizens for the country.

The argument that I want to bring forward is that in our education, we lost the key ingredient, which is the affective development in learning. In other words, we have not focused on how our learners should be equipped with emotional educational principles. Affective components of our education were marginalised or forgotten in favour of promoting skill development or manual learning. One of the reasons behind this lack is the way we conceptualised our educational policies, defining education in dichotomous ways.

For instance, as philosopher john Dewey says, ‘theory and practice, individual and group, public and private, method and subject matter, mind and behaviour, means and ends, and culture and vocation’ (Palmer et al., 2002, p. 197) are the ways that we defined our educational principles. Dewey’s educational philosophy is based on the key principle that the children should learn in the classroom where they learn the society through ‘miniature community and or embryonic society’ (Palmer et al., 2002, p. 196). It is vital for the students to learn this communal living, because in the larger canvas, they learn to live in the democratic society as elders. Communal empathy is thus a vital component in developing a healthy, democratic and caring society where each person has a place and respect.

Today, we focus on education, but the truth is we are living in a paradoxical era. Bruzzone (2024) argues that with this pandemic situation, the ongoing conflict between developed nations, and also the advancement of television and online technology, our young generation is in a conundrum. Living in these complex social terrains, our young generation is experiencing complex inner upheavals. He argues that,

The rhetoric of happiness and the entertainment industry keep children and adolescents in a state of intermittent distraction that prevents them from exploring their inner self, including its less appealing, grey areas. Cinema, TV, and video games elicit strong emotions, helping the young to evade the desert of boredom and apathy (Bruzzone, 2024, p.2).

Even though our young people are equipped with devices throughout their livelihood, more or less they are isolated. The media always exaggerates that with mobile technology and other online devices, we are connected to the world and are not isolated.

We also tend to think that we are a part of global citizenship. However, the truth is that most of us are becoming isolated though we are connected with others through technology. Hence, Bruzzone argues that in order to overcome such isolation, existential vacuum and indifference, people tend to experience adrenaline rushes through various risk behaviours, speeding, loud music, and psychotropic substances (Bruzzone, 2024).

Affective life

What I argue here is not to give up our engagements with the new technology or devices but to find ways of reawakening our emotional life within us. This affective life is still hidden in our life that our learners do not know how to find it; or rather, we have not taught them to unlock this emotional life within. Our education, as I argued earlier, does not have such intention or components where the learners can be equipped with emotional intelligence.

We have thrown away all the important aspects of such components in our educational system in favour of developing manual learners. These manual learners do not have such empathic life, affection, or emotional intelligence to deal with their own emotional lives, or they do not have knowledge to deal with others in the society. The result is what we have today: the merciless society where people are competing with each other to accumulate material wealth. Citing Galimberti (2007), Bruzzone further argues how this can create a societal issue when the individual cannot cope with his/her emotional life:

This inability to express and share emotions can sometimes explode, taking the form of uncontrolled aggression and impulsive and maladaptive ways of acting out: when this occurs, unacknowledged emotional experiences (of anger, frustration, a sense of inadequacy, fear, and so on) turn into words or acts of hatred and violence—usually towards vulnerable individuals–,flagging a growing dis-connect between acting, reasoning, and feeling: the heart is not in tune with thought nor thought with action (Bruzzone, 2024, p. 2).

Thus, our education has created this person who is struggling to connect with the heart; heart with the thought and thought with action. This dislocation of the heart with thought and action has resulted in developing antipathy towards the society. This antipathy also destabilizes the democratic social value systems. If we really need to re-establish a democratic society, we should first focus on our existing education system.

It is not all about how we integrate new technology and equipment to facilitate our learners but it is about how we allow our learners to first unlock their emotional life, and secondly think how they reconnect with the society. A new educational approach should be tailored to facilitate this vital objective. Hence, let me briefly discuss how creative arts and aesthetics can be useful for developing such individuals who will be empathic as well as critical towards the social changes taking place in this millennium.

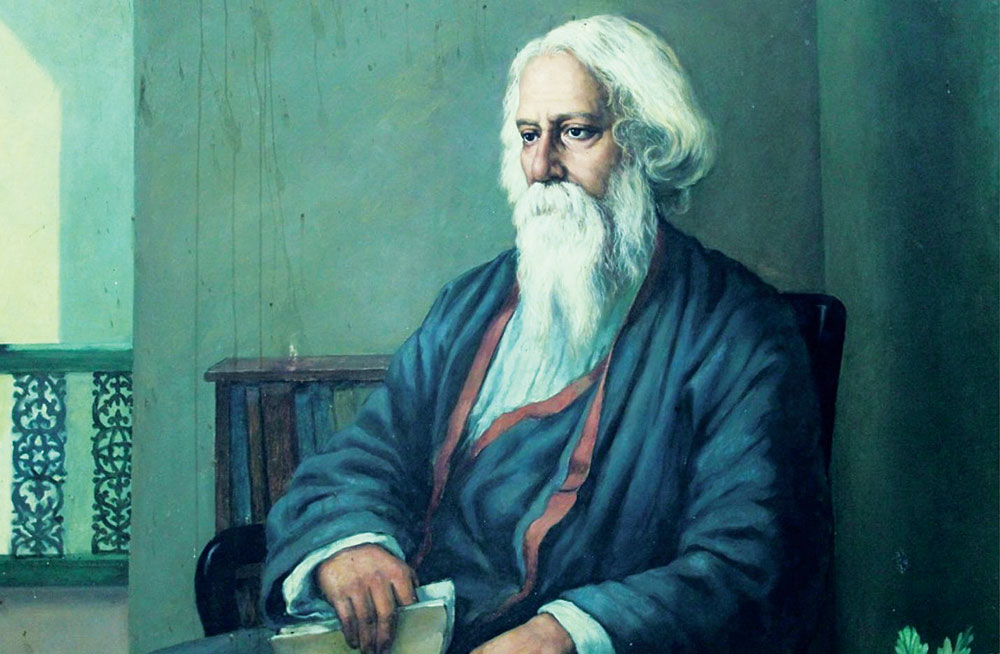

At this juncture, it is important to revisit one of the key thinkers and an educational philosopher, Rabindranath Tagore. Tagore is one of the few philosophers who have been thinking and developing an alternative learning approach through his Vishva Bharathi concept. He established Shanti Niketan where this new approach was primarily being tested. Encapsulating his philosophy of learning, he argued,

For us, the highest purpose of this world is not merely living in it, knowing it and making use of it, but realizing ourselves through expansion of sympathy and not dominating it, but comprehending and uniting it with ourselves in perfect union (Bhattacharya, 2014, p. 60).

As this statement clearly indicates, Tagore’s vision of education is developed for cultivating sympathy towards other humans and the environment alike. This education does not persuade the learner to think about his/her environment as something that can be commodified and utilized as material. The environment where the individual is living is also a living entity that is intertwined with human beings. Therefore, the individual should think in a different way to converge with the environment and find a place for co-living. In order to establish such an empathic educational approach, we need a different mode of educating young people. This Tagorean approach to education clearly emphasizes the value of the affective nature of education. It is the emotional life of the individual which is focused and cultivated through various means of teaching and learning.

Emotion and democracy

As of today, we lack this vital emotional component in our education. One of the fallacies behind this situation is that we tend to believe that emotions reside within ourselves, and they are private and personal. This is a misconception that is being sustained through our existing systems of education. However, on the contrary, emotions do not only provide richness to our own personal lives but they are also the primal tool that connects us with the outer world. In other words, we connect with other human beings in the society through our emotional arc. If the individual disconnects the communal engagement, this can result in destructive mannerism.

‘This disintegration of reciprocity, which weakens the social fabric, effectively leaves the individual isolated in a state of loneliness and uncertainty’ (Bruzzone, 2024, p. 13). This isolation and uncertainties of individuals can also have a negative impact on the healthy relationship with communities and, largely, on the democratic institutions. As scholars argue, this can be resulted in sustaining endogamous, xenophobic and violent neo-tribal grouping that have mushroomed in our society. This is what we have seen in the form of various nationalist upheavals in our society for the last few decades.

This tendency, therefore, leads us to further think about the value of emotional education and also its role in communal living. Further, emotions and emotional competency lead us to engage with other subjects, and also emphasizes that it is a bridge that is built between you and me and the world. When this bridge is broken, our connections between myself, you, and the world could be destabilized and shattered.

That is why scholars such as Bruzzone argue that ‘affectivity is also an ethical and political issue’ (Bruzzone, 2024, p. 12). It is ethical in the sense that my engagement or disengagement with the social beings are formed and developed through the emotional desires that I have inherited. Further, it is political, because, when the individual assumes that his/her existence relies on the communal existence, this assumption leads to political action of individuals. Hence, emotional education is vital for the healthy existence of a society. Cusinato, therefore, states that ‘emotional education is at the core of democracy’ (Cusinato Cited by Bruzzone, 2024, p, 13).

Finally, I would like to highlight one of the brilliant minds of our time, Prof Martha C. Nussbaum and her ideas on why arts education is vital for a continuation of democracy, and also how emotional education is important to achieve this (Helsinki Collegium, 2024). Today, as a civilization, we are confronting various and complex issues threatening the continuation of the human race. These key issues are not limited to countries or nations. They are applicable to all human beings currently living in the world.

Environmental crisis, global warming, food security, poverty, and war are some of the recurrent issues we face today. In order to focus on these larger humanitarian crises, how could we equip our students to think in broader ways to tackle these complex issues? Nussbaum provides us some important points to think on how we could design our education system where the individual can be more empathetic and passionately engage with worldly phenomena. According to her, we need citizens who have the capacity to think and see the world as other people see the world; need to develop the capacity for genuine concern of others, near and distant; teach real things about other groups in the society and learn to reject stereotypes; and promote accountability and critical thinking, ‘the skill and courage it requires to raise a dissenting voice’ (Nussbaum, 2016, p. 45-46).

Conclusion

Nussbaum’s recent works largely focus on how human emotions are connected to the establishment of democratic societies in the world. Arts, culture, and humanities play significant role in promoting positive emotions amongst participants. It also promotes wellbeing and happiness which are vital for a healthy society. Today, we have a new government. This government often emphasizes the importance of investing in education, from primary levels to higher education. They have shown the commitment to change the existing stale education systems which need drastic and constructive criticisms to change for a better system. Thus, we, as educators, thoroughly believe that it is time for us to revisit what we have taught and how we have taught our younger generation for decades. It is time for us to rethink new ways of tailoring our education system where we could promote empathy and develop empathetic citizens who care about others and the environment we live in.

Thank you.

References

Bhattacharya, Kumkum. 2014. Rabindranath Tagore: Adventure of Ideas and Innovative Practices in Education. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Bruzzone, Daniele. 2024. Emotional Life: Phenomenology, Education and Care. Springer Nature.

Harshana Rambukwella. 2024. “The Cultural Life of Democracy: Notes on Popular Sovereignty, Culture and Arts in Sri Lanka’s Aragalaya.” South Asian Review, July, 1–16.https://doi.org/10.1080/02759527.2024.2380179 .

Helsinki Collegium. 2024. “Democracy and Emotions– a Dialogue with Philosopher Martha C. Nussbaum.” YouTube. June 6, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p3xdcfbE3KA.

Jayasinghe, Saroj. 2024. “Arts and Humanities in Medical Education: Current and Future.” Jaffna Medical Journal 36 (1): 3–6. https://doi.org/10.4038/jmj.v36i1.202.

Jayasinghe, Saroj, and Santhushya Fernando. 2023. “Developments in Medical Humanities in Sri Lanka: A Call for Regional and Global Action.” The Asia Pacific Scholar 8 (4): 1–4.https://doi.org/10.29060/taps.2023-8-4/gp2878.

Karunanayake, Panduka. 2021. Ruptures in Sri Lanka’s Education: Genesis, Present Status and Reflections. Nugegoda: Sarasavi Publishers.

Nussbaum, Martha C. 2016. Not for Profit Why Democracy Needs the Humanities. Princeton University Press.

Palmer, Joy, David Cooper, and Liora Bresler, eds. 2002. Fifty Major Thinkers on Education. Routledge.

Uyangoda, Jayadeva, ed. 2023. Democracy and Democratisation in Sri Lanka: Paths, Trends and Imaginations. 1st ed. Vol. 1 and 2. Colombo: Bandaranaike Centre for International Studies.

Short bio of the speaker

Saumya Liyanage (PhD) is an actor both in theatre and film and also working as a professor in Drama and Theatre at the Department of Theatre Ballet and Modern Dance, Faculty of Dance and Drama, University of the Visual and Performing Arts (UVPA), Colombo, Sri Lanka. Professor Liyanage was the former Dean of the Faculty of Graduate Studies, UVPA Colombo and currently holds the position of the Director of the Social Reconciliation Centre, UVPA Colombo.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Himansi Dehigama for proofreading the final manuscript of this keynote speech.

This keynote is delivered at the annual sessions of the Faculty of Education, Open University of Sri Lanka on the 6th of February 2025.

by Professor Saumya Liyanage

(BA Kelaniya, MCA Flinders, Australia, PhD La Trobe, Australia)

Department of Theatre Ballet and Modern Dance

Faculty of Dance and Drama

University of Visual and Performing Arts, Colombo, Sri Lanka

Features

Inescapable need to deal with the past

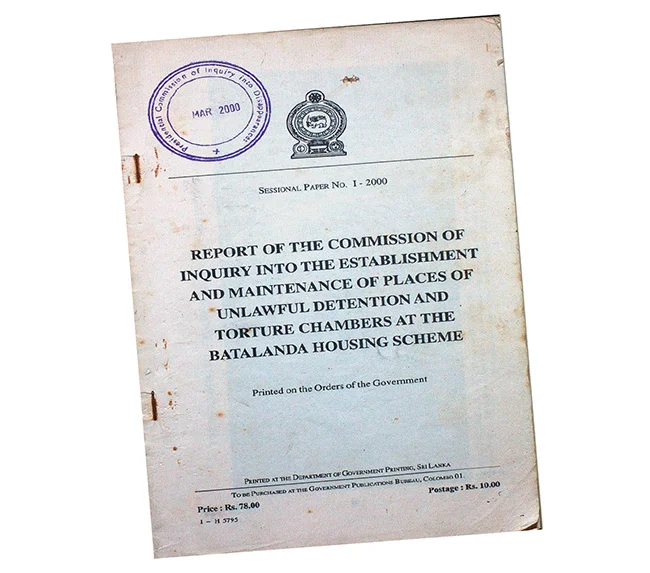

The sudden reemergence of two major incidents from the past, that had become peripheral to the concerns of people today, has jolted the national polity and come to its centre stage. These are the interview by former president Ranil Wickremesinghe with the Al Jazeera television station that elicited the Batalanda issue and now the sanctioning of three former military commanders of the Sri Lankan armed forces and an LTTE commander, who switched sides and joined the government. The key lesson that these two incidents give is that allegations of mass crimes, whether they arise nationally or internationally, have to be dealt with at some time or the other. If they are not, they continue to fester beneath the surface until they rise again in a most unexpected way and when they may be more difficult to deal with.

In the case of the Batalanda interrogation site, the sudden reemergence of issues that seemed buried in the past has given rise to conjecture. The Batalanda issue, which goes back 37 years, was never totally off the radar. But after the last of the commission reports of the JVP period had been published over two decades ago, this matter was no longer at the forefront of public consciousness. Most of those in the younger generations who were too young to know what happened at that time, or born afterwards, would scarcely have any idea of what happened at Batalanda. But once the issue of human rights violations surfaced on Al Jazeera television they have come to occupy centre stage. From the day the former president gave his fateful interview there are commentaries on it both in the mainstream media and on social media.

There seems to be a sustained effort to keep the issue alive. The issues of Batalanda provide good fodder to politicians who are campaigning for election at the forthcoming Local Government elections on May 6. It is notable that the publicity on what transpired at Batalanda provides a way in which the outcome of the forthcoming local government elections in the worst affected parts of the country may be swayed. The problem is that the main contesting political parties are liable to be accused of participation in the JVP insurrection or its suppression or both. This may account for the widening of the scope of the allegations to include other sites such as Matale.

POLITICAL IMPERATIVES

The emergence at this time of the human rights violations and war crimes that took place during the LTTE war have their own political reasons, though these are external. The pursuit of truth and accountability must be universal and free from political motivations. Justice cannot be applied selectively. While human rights violations and war crimes call for universal standards that are applicable to all including those being committed at this time in Gaza and Ukraine, political imperatives influence what is surfaced. The sanctioning of the four military commanders by the UK government has been justified by the UK government minister concerned as being the fulfilment of an election pledge that he had made to his constituents. It is notable that the countries at the forefront of justice for Sri Lanka have large Tamil Diasporas that act as vote banks. It usually takes long time to prosecute human rights violations internationally whether it be in South America or East Timor and diasporas have the staying power and resources to keep going on.

In its response to the sanctions placed on the military commanders, the government’s position is that such unilateral decisions by foreign government are not helpful and complicate the task of national reconciliation. It has faced criticism for its restrained response, with some expecting a more forceful rebuttal against the international community. However, the NPP government is not the first to have had to face such problems. The sanctioning of military commanders and even of former presidents has taken place during the periods of previous governments. One of the former commanders who has been sanctioned by the UK government at this time was also sanctioned by the US government in 2020. This was followed by the Canadian government which sanctioned two former presidents in 2023. Neither of the two governments in power at that time took visibly stronger stands.

In addition, resolutions on Sri Lanka have been a regular occurrence and have been passed over the Sri Lankan government’s opposition since 2012. Apart from the very first vote that took place in 2009 when the government promised to take necessary action to deal with the human rights violations of the past, and won that vote, the government has lost every succeeding vote with the margins of defeat becoming bigger and bigger. This process has now culminated in an evidence gathering unit being set up in Geneva to collect evidence of human rights violations in Sri Lanka that is on offer to international governments to use. This is not a safe situation for Sri Lankan leaders to be in as they can be taken before international courts in foreign countries. It is important for Sri Lanka’s sovereignty and dignity as a country that this trend comes to an end.

COMPREHENSIVE SOLUTION

A peaceful future for Sri Lanka requires a multi-dimensional approach that addresses the root causes of conflict while fostering reconciliation, justice, and inclusive development. So far the government’s response to the international pressures is to indicate that it will strengthen the internal mechanisms already in place like the Office on Missing Persons and in addition to set up a truth and reconciliation commission. The difficulty that the government will face is to obtain a national consensus behind this truth and reconciliation commission. Tamil parties and victims’ groups in particular have voiced scepticism about the value of this mechanism. They have seen commissions come and commissions go. Sinhalese nationalist parties are also highly critical of the need for such commissions. As the Nawaz Commission appointed to identify the recommendations of previous commissions observed, “Our island nation has had a surfeit of commissions. Many witnesses who testified before this commission narrated their disappointment of going before previous commissions and achieving nothing in return.”

Former minister Prof G L Peiris has written a detailed critique of the proposed truth and reconciliation law that the previous government prepared but did not present to parliament.

In his critique, Prof Peiris had drawn from the South African truth and reconciliation commission which is the best known and most thoroughly implemented one in the world. He points out that the South African commission had a mandate to cover the entire country and not only some parts of it like the Sri Lankan law proposes. The need for a Sri Lankan truth and reconciliation commission to cover the entire country and not only the north and east is clear in the reemergence of the Batalanda issue. Serious human rights violations have occurred in all parts of the country, and to those from all ethnic and religious communities, and not only in the north and east.

Dealing with the past can only be successful in the context of a “system change” in which there is mutual agreement about the future. The longer this is delayed, the more scepticism will grow among victims and the broader public about the government’s commitment to a solution. The important feature of the South African commission was that it was part of a larger political process aimed to build national consensus through a long and strenuous process of consultations. The ultimate goal of the South African reconciliation process was a comprehensive political settlement that included power-sharing between racial groups and accountability measures that facilitated healing for all sides. If Sri Lanka is to achieve genuine reconciliation, it is necessary to learn from these experiences and take decisive steps to address past injustices in a manner that fosters lasting national unity. A peaceful Sri Lanka is possible if the government, opposition and people commit to truth, justice and inclusivity.

by Jehan Perera

Features

Unleashing Minds: From oppression to liberation

Education should be genuinely ‘free’—not just in the sense of being free from privatisation, but also in a way that empowers students by freeing them from oppressive structures. It should provide them with the knowledge and tools necessary to think critically, question the status quo, and ultimately liberate themselves from oppressive systems.

Education should be genuinely ‘free’—not just in the sense of being free from privatisation, but also in a way that empowers students by freeing them from oppressive structures. It should provide them with the knowledge and tools necessary to think critically, question the status quo, and ultimately liberate themselves from oppressive systems.

Education as an oppressive structure

Education should empower students to think critically, challenge oppression, and envision a more just and equal world. However, in its current state, education often operates as a mechanism of oppression rather than liberation. Instead of fostering independent thinking and change, the education system tends to reinforce the existing power dynamics and social hierarchies. It often upholds the status quo by teaching conformity and compliance rather than critical inquiry and transformation. This results in the reproduction of various inequalities, including economic, racial, and social disparities, further entrenching divisions within society. As a result, instead of being a force for personal and societal empowerment, education inadvertently perpetuates the very systems that contribute to injustice and inequality.

Education sustaining the class structure

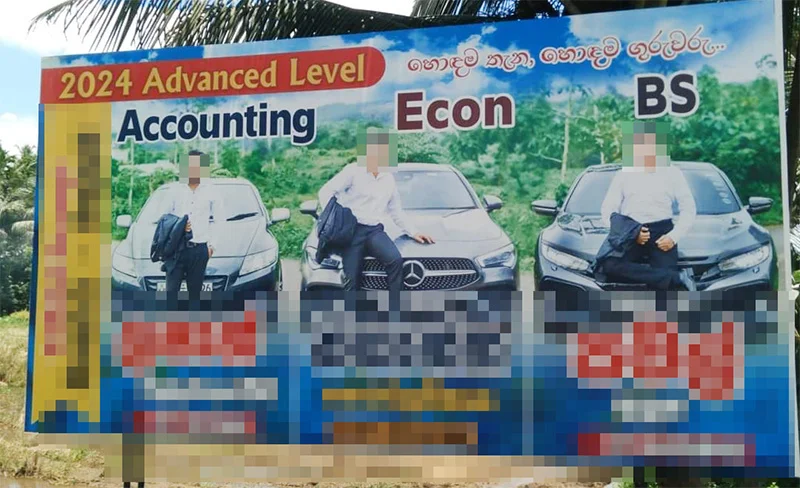

Due to the widespread privatisation of education, the system continues to reinforce and sustain existing class structures. Private tuition centres, private schools, and institutions offering degree programmes for a fee all play a significant role in deepening the disparities between different social classes. These private entities often cater to the more affluent segments of society, granting them access to superior education and resources. In contrast, students from less privileged backgrounds are left with fewer opportunities and limited access to quality education, exacerbating the divide between the wealthy and the underprivileged. This growing gap in educational access not only limits social mobility but also perpetuates a cycle where the privileged continue to secure better opportunities while the less fortunate struggle to break free from the constraints of their socio-economic status.

Gender Oppression

Education subtly perpetuates gender oppression in society by reinforcing stereotypes, promoting gender insensitivity, and failing to create a gender-sensitive education system. And some of the policymakers do perpetuate this gender insensitive education by misinforming people. In a recent press conference, one of the former members of Parliament, Wimal Weerawansa, accused gender studies of spreading a ‘disease’ among students. In the year 2025, we are still hearing such absurdities discouraging gender studies. It is troubling and perplexing to hear such outdated and regressive views being voiced by public figures, particularly at a time when societies, worldwide, are increasingly embracing diversity and inclusion. These comments not only undermine the importance of gender studies as an academic field but also reinforce harmful stereotypes that marginalise individuals who do not fit into traditional gender roles. As we move forward in an era of greater social progress, such antiquated views only serve to hinder the ongoing work of fostering equality and understanding for all people, regardless of gender identity.

Students, whether in schools or universities, are often immersed in an educational discourse where gender is treated as something external, rather than an essential aspect of their everyday lives. In this framework, gender is framed as a concern primarily for “non-males,” which marginalises the broader societal impact of gender issues. This perspective fails to recognise that gender dynamics affect everyone, regardless of their gender identity, and that understanding and addressing gender inequality is crucial for all individuals in society.

A poignant example of this issue can be seen in the recent troubling case of sexual abuse involving a medical doctor. The public discussion surrounding the incident, particularly the media’s decision to disclose the victim’s confidential statement, is deeply concerning. This lack of respect for privacy and sensitivity highlights the pervasive disregard for gender issues in society.

What makes this situation even more alarming is that such media behaviour is not an isolated incident, but rather reflects a broader pattern in a society where gender sensitivity is often dismissed or ignored. In many circles, advocating for gender equality and sensitivity is stigmatised, and is even seen as a ‘disease’ or a disruptive force to the status quo. This attitude contributes to a culture where harmful gender stereotypes persist, and where important conversations about gender equity are sidelined or distorted. Ultimately, this reflects the deeper societal need for an education system that is more attuned to gender sensitivity, recognising its critical role in shaping the world students will inherit and navigate.

To break free from these gender hierarchies there should be, among other things, a gender sensitive education system, which does not limit gender studies to a semester or a mere subject.

Ragging

The inequality that persists in class and regional power structures (Colombo and non-Colombo division) creeps into universities. While ragging is popularly seen as an act of integrating freshers into the system, its roots lie in the deeply divided class and ethno-religious divisions within society.

In certain faculties, senior students may ask junior female students to wear certain fabrics typically worn at home (cheetta dresses) and braid their hair into two plaits, while male students are required to wear white, long-sleeved shirts without belts. Both men and women must wear bathroom slippers. These actions are framed as efforts to make everyone equal, free from class divisions. However, these gendered and ethicised practices stem from unequal and oppressive class structures in society and are gradually infiltrating university culture as mechanisms of oppression.The inequality that persists in gradually makes its way into academic institutions, particularly universities.

These practices are ostensibly intended to create a sense of uniformity and equality among students, removing visible markers of class distinction. However, what is overlooked is that these actions stem from deeply ingrained and unequal social structures that are inherently oppressive. Instead of fostering equality, they reinforce a system where hierarchical power dynamics in the society—rooted in class, gender, and region—are confronted with oppression and violence which is embedded in ragging, creating another system of oppression.

Uncritical Students

In Sri Lanka, and in many other countries across the region, it is common for university students to address their lecturers as ‘Sir’ and ‘Madam.’ This practice is not just a matter of politeness, but rather a reflection of deeply ingrained societal norms that date back to the feudal and colonial eras. The use of these titles reinforces a hierarchical structure within the educational system, where authority is unquestioned, and students are expected to show deference to their professors.

Historically, during colonial rule, the education system was structured around European models, which often emphasised rigid social distinctions and the authority of those in power. The titles ‘Sir’ and ‘Madam’ served to uphold this structure, positioning lecturers as figures of authority who were to be respected and rarely challenged. Even after the end of colonial rule, these practices continued to permeate the education system, becoming normalised as part of the culture.

This practice perpetuates a culture of obedience and respect for authority that discourages critical thinking and active questioning. In this context, students are conditioned to see their lecturers as figures of unquestionable authority, discouraging dialogue, dissent, or challenging the status quo. This hierarchical dynamic can limit intellectual growth and discourage students from engaging in open, critical discussions that could lead to progressive change within both academia and society at large.

Unleashing minds

The transformation of these structures lies in the hands of multiple parties, including academics, students, society, and policymakers. Policymakers must create and enforce policies that discourage the privatisation of education, ensure equal access for all students, regardless of class dynamics, gender, etc. Education should be regarded as a fundamental right, not a privilege available only to a select few. Such policies should also actively promote gender equality and inclusivity, addressing the barriers that prevent women, LGBTQ+ individuals, and other marginalised genders from accessing and succeeding in education. Practices that perpetuate gender inequality, such as sexism, discrimination, or gender-based violence, need to be addressed head-on. Institutions must prioritise gender studies and sensitivity training to cultivate an environment of respect and understanding, where all students, regardless of gender, feel safe and valued.

At the same time, the micro-ecosystems of hierarchy within institutions—such as maintaining outdated power structures and social divisions—must be thoroughly examined and challenged. Universities must foster environments where critical thinking, mutual respect, and inclusivity—across both class and gender—are prioritised. By creating spaces where all minds can flourish, free from the constraints of entrenched hierarchies, we can build a more equitable and intellectually vibrant educational system—one that truly unleashes the potential of all students, regardless of their social background.

(Anushka Kahandagamage is the General Secretary of the Colombo Institute for Human Sciences)

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.

By Anushka Kahandagamage

Features

New vision for bassist Benjy

It’s a known fact that whenever bassist Benjy Ranabahu booms into action he literally lights up the stage, and the exciting news I have for music lovers, this week, is that Benjy is coming up with a new vision.

One thought that this exciting bassist may give the music scene a layoff, after his return from the Seychelles early this year.

At that point in time, he indicated to us that he hasn’t quit the music scene, but that he would like to take a break from the showbiz setup.

“I’m taking things easy at the moment…just need to relax and then decide what my future plans would be,” he said.

However, the good news is that Benjy’s future plans would materialise sooner than one thought.

Yes, Benjy is putting together his own band, with a vision to give music lovers something different, something dynamic.

He has already got the lineup to do the needful, he says, and the guys are now working on their repertoire.

The five-piece lineup will include lead, rhythm, bass, keyboards and drums and the plus factor, said Benjy, is that they all sing.

A female vocalist has also been added to this setup, said Benjy.

“She is relatively new to the scene, but with a trained voice, and that means we have something new to offer music lovers.”

The setup met last week and had a frank discussion on how they intend taking on the music scene and everyone seems excited to get on stage and do the needful, Benjy added.

Benjy went on to say that they are now spending their time rehearsing as they are very keen to gel as a team, because their skills and personalities fit together well.

“The guys I’ve got are all extremely talented and skillful in their profession and they have been around for quite a while, performing as professionals, both here and abroad.”

Benjy himself has performed with several top bands in the past and also had his own band – Aquarius.

Aquarius had quite a few foreign contracts, as well, performing in Europe and in the Middle East, and Benjy is now ready to do it again!

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoSri Lanka’s eternal search for the elusive all-rounder

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoCelebrating 25 Years of Excellence: The Silver Jubilee of SLIIT – PART I

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoGnanasara Thera urged to reveal masterminds behind Easter Sunday terror attacks

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoCEB calls for proposals to develop two 50MW wind farm facilities in Mullikulam

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoAIA Higher Education Scholarships Programme celebrating 30-year journey

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoNotes from AKD’s Textbook

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoBid to include genocide allegation against Sri Lanka in Canada’s school curriculum thwarted

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoComBank crowned Global Finance Best SME Bank in Sri Lanka for 3rd successive year