Features

A 20-year reflection on housing struggles of Tsunami survivors

Revisiting field research in Ampara

by Prof. Amarasiri de Silva

The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, also known as the Boxing Day tsunami, triggered by a magnitude 9.1 earthquake off the coast of Sumatra on 26 Dec., 2004, had a catastrophic impact on Sri Lanka. It is estimated to have released energy equivalent to 23,000 Hiroshima-type atomic bombs, wiping out hundreds of communities in minutes. The tsunami struck Sri Lanka’s eastern and southern coasts approximately two hours after the earthquake. The eastern shores, facing the earthquake’s epicenter, bore the brunt of the waves, affecting settlements on the east coast. The tsunami displaced many families and devastated villages and communities in the affected districts of Sri Lanka. Although Boxing Day is associated with exchanging gifts after Christmas and was a time to give to the less fortunate, it brought havoc in Sri Lanka to many communities. It resulted in approximately 31,229 deaths and 4,093 people missing. In terms of the dead and missing numbers, Sri Lanka’s toll was second only to Indonesia (126,804, missing 93,458, displaced 474,619). Twenty-five beach hotels were severely damaged, and another 6 were completely washed away. More than 240 schools were destroyed or sustained severe damage. Several hospitals, telecommunication networks, coastal railway networks, etc., were also damaged. In addition, one and a half million people were displaced from their homes.

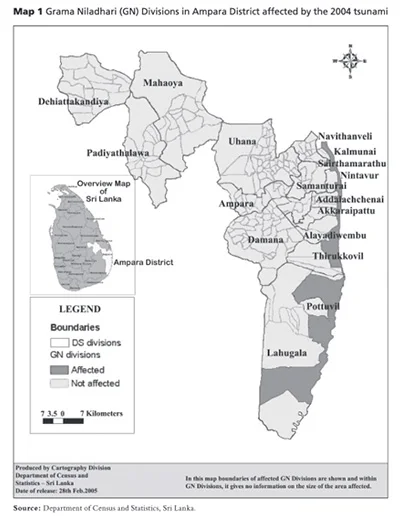

Ampara district was a hard-hit district, where more than 10,000 people died. A Galle bound train from Colombo, carrying about 1,700 passengers visiting their ancestral homes and villages, on the Sunday after the Christmas holidays, was struck by the tsunami near Telwatta; most of them were killed.

About 8,000 people were killed in the northeast region, which the LTTE controlled at the time. The Ampara district was a hard-hit district, with more than 10,000 people dying and many more displaced. In sympathy with the victims, the Saudi Arabian government established a grant to construct houses to assist 500 displaced families in Ampara in 2009. The Saudi Envoy in Colombo presented the house keys to President Mahinda Rajapaksa in 2011 for distribution to tsunami victims in the Ampara district. However, due to the protests by local majoritarian ethnic groups, the government intervened, and a court ruling halted the housing distribution to the victims, mandating that houses be allocated according to the country’s population ratio. The project includes residential units and amenities such as a school, a supermarket complex, a hospital, and a mosque, making it unique for Muslim people. Saudi government ambassador Khalid Hamoud Alkahtani engaged in discussions with the Sri Lankan government to sort out the issues and agreed to give the houses to the respective victims.

Immediate Recovery

The immediate relief work was initiated just after the disaster, and the government had financial and moral support from local people and countries worldwide. As most displaced people were children and women, restoring at least basic education facilities for affected children was a high priority. By mid-year, 85 percent of the children in tsunami-affected areas were back in school, which showed that the relief programme in school education was a success.

Relief efforts for households included the provision of finances to meet immediate needs. Compensation of Rs.15,000 (US$150) was offered for victims towards funeral expenses; livelihood support schemes included Payment of Rs.375 (US$3.75) in cash and rations for each member of a family unit per week, a payment of Rs. 2,500 (US$25) towards kitchen utensils per family. These initial measures were largely successful, though there were some problems with a lack of coordination, as witnessed. (See Map 1)

The most considerable financing needs were in the housing sector. The destruction of private assets was substantial (US$700 million), in addition to public infrastructure and other assets. Loss of current output in the fisheries and tourism sectors—which were severely affected—was estimated at US$200 million and US$130 million, respectively.

2004 tsunami-impacted zone. (Image courtesy Reliefweb)

Strands of Hope: Progress Made for Tsunami-Affected Communities of Sri Lanka

By mid-June 2005, the number of displaced people was down to 516,000 from approximately 800,000 immediately after the tsunami, as people went home—even if the homes in question were destroyed or damaged—and were taken off the books then. At first, an estimated 169,000 people living in schools and tents were mainly transferred to transitional shelters/camps—designed to serve as a stopgap between emergency housing and permanent homes. This transitional shelter was only supplied to affected households in the buffer zone.

By late August 2005, The Task Force for Rebuilding the Nation (TAFREN) estimated that 52,383 transitional shelters, accommodating an estimated 250,000 tsunami-affected people, had been completed since February 2005 at 492 sites. Those transitional housing programme shelters were expected to be completed with 55,000 by the end of September 2005. This goal seems more than achievable. I did not find evidence to show that it has been achieved.

I did my field research in Ampara district with support from UNDP Colombo, the Department for Research Cooperation, and the Swedish International Development Cooperation.

My research shows that the tsunami affected families in Muslim settlements along the East Coast had a severe housing problem for two reasons.

• First, the GoSL has declared that land within 65 meters of the sea is unsafe for living due to possible seismic effects, and people are thus prohibited from engaging in any construction in that beach area. This land strip is the traditional living area of the Muslims, particularly the fisher folk. Families living along the narrow beach strip have not been offered alternative land or adequate compensation to buy land outside the 65-metre zone.

• Second, the LTTE has prohibited Muslims from building houses on land purchased for them by outside agencies on the pretext that it belongs to the Tamils.

The GoSL established several institutions as a response strategy for post-tsunami recovery after the failure of P-TOMS. The Task Force for Rebuilding the Nation (TAFREN), the Task Force for Relief (TAFOR), and the Tsunami Housing Reconstruction Unit (THRU) were the lead agencies created through processes involving private and public sector participation. In November 2005, following the election of President Mahinda Rajapaksa, the Reconstruction and Development Agency (RADA)was set up. This became an authority with executive powers following the parliamentary ratification of the RADA Act in 2006. RADA’s mandate was to accelerate reconstruction and development activities in the affected areas, functionally replacing all the tsunami organizations and a significant part of the former RRR Ministry. According to RADA, the total number of houses built so far (as of May 2006) in Ampara is 629, while the total housing units pledged is 6,169. At the time of the research (March to June 2006), no housing projects were completed in a predominantly Muslim area.

Compensation for damaged houses was not based on a consistent scheme. As a result, some families received large sums, while others did not get any money. In some instances, those who collected compensation were not the affected families. The Auditor General, S.C. Mayadunne, noted that Payment of an excessive amount, even for minor damages, is due to the payments being made without assessing the cost of restoring the houses to normal condition. (For example, Rs. 100,000 had been paid for minor damages of Rs. 10,000) … Payments made without identifying the value of the damaged houses, thus resulting in heavy expenditure by the government (For example, a sum of Rs. 250,000 had been paid for the destruction of a temporary house valued at Rs. 10,000) (Mayadunne, 2005, p. 8). That compensation was not paid according to an acceptable scheme, which led to agitation among the affected people and provided an opportunity for political manipulation. The LTTE and the TRO requested direct aid for reconstruction work in LTTE-controlled areas. The poor response of the GoSL to this demand was interpreted as indifference on its part towards ethnic minorities in Ampara. Meanwhile, the GoSL provided direct support for tsunami-affected communities in southern Sri Lanka, where the majority were Sinhalese, strengthening this allegation.

Land scarcity in tsunami-affected Ampara and disputes over landownership in the area were the main reasons for not completing the housing programmes. The LTTE contended that the land identified for building houses by the GoSL or purchased by civil society organisations for constructing such houses belongs to the Tamils, an ideology based on a myth of their own, a Tamil hereditary Homeland—paarampariyamaana taayakam’ (Peebles, 1990, p. 41). Consequently, housing programmes could not be implemented at that time.

The land question in the Eastern Province has a history that dates back to 1951 when the Gal Oya Colonisation scheme was established. According to the minority version of this history, in a report submitted by Dr. Hasbullah and his colleagues, it shows that the colonists were selected overwhelmingly from among the Sinhalese rather than the Muslims and Tamils, who were a majority in Ampara at that time, and, as a result, the ethnic balance of Ampara District was disrupted. However, conversely, B.H. Farmer reported in 1957 that Tamils, especially Jaffna Tamils, were ‘chary’ and did not have a ‘tradition of migration,’ which was the apparent reason for less Tamil representation among the colonists of Gal Oya. According to Farmer, up to December 31, 1953, between five and 16 percent of the colonists were chosen from the Districts of Batticaloa, Jaffna and Trincomalee, predominantly Tamil. Contradictory evidence (with a political coloring following the recent rise of ethnicity in this discourse) reports by Dr. Hasbullah that 100,000 acres of agricultural land in the East have been ‘illegally transferred from Muslims to the Tamils’ since the 1990s. The Tamils, however, believe that the land in the Eastern Province is part and parcel of the Tamil Homeland. This new political ideology of landownership that emerged at that time in the ethnopolitical context of the Eastern Province has intensified land (re)claiming in Ampara by Muslims and Tamils.

According to Tamil discourse, the increase in the value of land in Ampara over the past two decades has led to rich Muslims purchasing land belonging to poor Tamils, resulting in ethnic homogenization in the coastal areas of the District in favor of the Muslims. ‘Violence against Tamils was also used in some areas to push out the numerically small Tamil service caste communities’ as Hasbullah says. In a situation with an ideological history of land disputes, finding new land for the construction of houses for Muslim communities affected by the tsunami posed a challenge at that time.

In the face of this challenge, Muslims in Ampara sought assistance from Muslim politicians and organisations that willingly came forward to assist them. The efforts made by these politicians and civil society organisations to erect houses for tsunami-affected Muslim families were forcibly curtailed by the LTTE. Consequently, a proposed housing program for Muslims in Kinnayady Kiramam in Kaththankudi was abandoned in 2005. Development of the four acres of land bought by the Memon Sangam in Colombo for tsunami victims of Makbooliya in Marathamunai was prohibited in 2005. Similar occurrences have been reported in Marathamunai Medduvedday. Mrs. Ferial Ashraff, at that time Minister of Housing and Common Amenities, wanted to build houses in Marathamunai, Periyaneelavanai DS division (Addaippallam), the Pandirippu Muslim area, and in Oluvil–Palamunai, but the LTTE proscribed all such initiatives.

In the face of this challenge, Muslims in Ampara sought assistance from Muslim politicians and organisations that willingly came forward to assist them. The efforts made by these politicians and civil society organisations to erect houses for tsunami-affected Muslim families were forcibly curtailed by the LTTE. Consequently, a proposed housing program for Muslims in Kinnayady Kiramam in Kaththankudi was abandoned in 2005. Development of the four acres of land bought by the Memon Sangam in Colombo for tsunami victims of Makbooliya in Marathamunai was prohibited in 2005. Similar occurrences have been reported in Marathamunai Medduvedday. Mrs. Ferial Ashraff, at that time Minister of Housing and Common Amenities, wanted to build houses in Marathamunai, Periyaneelavanai DS division (Addaippallam), the Pandirippu Muslim area, and in Oluvil–Palamunai, but the LTTE proscribed all such initiatives.

The Islamabad housing scheme in Kalmunai Muslim DS division and the construction of houses by Muslim individuals in Karaithivu were banned, and threats were issued by the LTTE and a Tamil military organisation called Ellai Padai (Boundary Forces). Because the GoSL and the intervening agencies could not resolve the housing problem, the affected communities became disillusioned and lost confidence in the GoSL departments, aid agencies, and international NGOs. Much effort and resources were wasted in finding land and designing housing programmes that have not materialised. Some funds pledged by external agencies failed to materialise, causing harm to low-income families. Efforts to provide housing for tsunami-affected people in the Ampara District at that time highlighted their vulnerability to LTTE threats and the power politics of participating agencies. Regarding housing and land issues, the Muslim people of Ampara adopted two approaches to address their challenges. First, in some cases, they reached a compromise with the LTTE, agreeing that upon completion of a housing project, a portion of the houses would be allocated to the Tamil community under LTTE supervision.

For instance, this approach proved successful in the Islamabad housing programme, which was halfway complete as of the time of the research (March–June 2006). Similarly, a housing scheme in Ninthavur followed a comparable compromise with the LTTE. According to Mohamed Mansoor, the then President of the Centre for East Lanka Social Service, 22 of the 100 houses were to be allocated to the Tamil community upon completion. This allocation was deemed reasonable because Muslims owned 80 percent of the land in the area, while Tamils owned 20 percent. At the time of the author’s fieldwork, approximately 30 houses had been completed at this site. I don’t know what happened afterward.

The second approach adopted by the people was to build houses in the areas they had lived in before the tsunami, despite construction being prohibited within 65 meters of the sea. Muslims in Marathamunai knew they would not be allocated any land for housing and sought funds from organisations such as the Eastern Human Economic Development to construct homes on their original plots. The affected individuals have made efforts to urge their leaders to engage with the TRO and the LTTE to reclaim the funds borrowed by Muslim people and organisations to purchase land. The four-acre plot that the Memon Society had acquired for housing development was sold to a Tamil organisation for Rs. 1,000,000 (roughly USD 10,000) and was one such land in question.

The national political forces operating in Ampara have deprived the poor (Muslim) fisher folk of their right to land and build houses in their villages. These communities have resorted to non-violent strategies involving accepting the status quo without questioning it and fighting for their rights. The passivity among the poor affected families is a result of them not having representation in the civil society organisations in the area. These bodies are run by elites who do not wish to contest the GoSL rule of a 65-metre buffer zone or LTTE land claims. The tsunami not only washed away the houses and took the land of the poor communities that lived by the sea, but it also made them even poorer, more marginalised, and more ethnically segregated.

Here, 20 years later, it is time that justice was done to the Muslim families in the Ampara district who were severely hit by the tsunami. It is also a significant and timely commitment made by President Dissanayake to offer 500 houses to the Muslim tsunami victims. Such a promise is overdue and essential, as these marginalised communities have desperately needed a voice and action in their favour for over 20 years. Delivery of such homes to the victims would be an important step in restoring social harmony and the dignity and livelihoods of those affected by the tragic incident.

Features

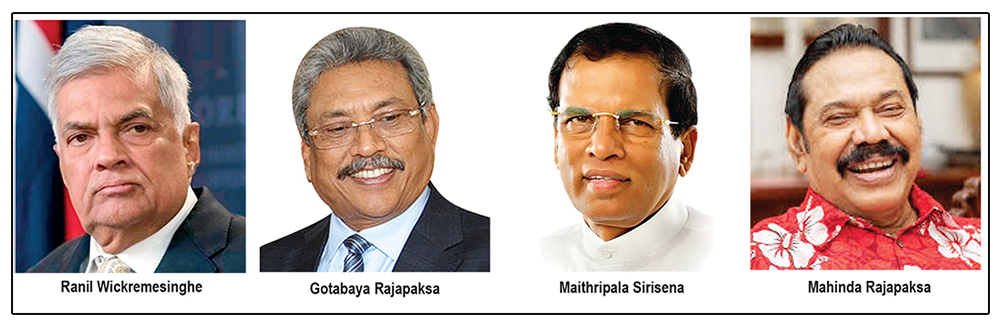

Reconciliation, Mood of the Nation and the NPP Government

From the time the search for reconciliation began after the end of the war in 2009 and before the NPP’s victories at the presidential election and the parliamentary election in 2024, there have been four presidents and four governments who variously engaged with the task of reconciliation. From last to first, they were Ranil Wickremesinghe, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, Maithripala Sirisena and Mahinda Rajapaksa. They had nothing in common between them except they were all different from President Anura Kumara Dissanayake and his approach to reconciliation.

The four former presidents approached the problem in the top-down direction, whereas AKD is championing the building-up approach – starting from the grassroots and spreading the message and the marches more laterally across communities. Mahinda Rajapaksa had his ‘agents’ among the Tamils and other minorities. Gotabaya Rajapaksa was the dummy agent for busybodies among the Sinhalese. Maithripala Sirisena and Ranil Wickremesinghe operated through the so called accredited representatives of the Tamils, the Muslims and the Malaiayaka (Indian) Tamils. But their operations did nothing for the strengthening of institutions at the provincial and the local levels. No did they bother about reaching out to the people.

As I recounted last week, the first and the only Northern Provincial Council election was held during the Mahinda Rajapaksa presidency. That nothing worthwhile came out of that Council was not mainly the fault of Mahinda Rajapaksa. His successors, Maithripala Sirisena and Ranil Wickremesinghe as Prime Minister, with the TNA acceding as a partner of their government, cancelled not only the NPC but also all PC elections and indefinitely suspended the functioning of the country’s nine elected provincial councils. Now there are no elected councils, only colonial-style governors and their secretaries.

Hold PC Elections Now

And the PC election can, like so many other inherited rotten cans, is before the NPP government. Is the NPP government going to play footsie with these elections or call them and be done with it? That is the question. Here are the cons and pros as I see them.

By delaying or postponing the PC elections President AKD and the NPP government are setting themselves up to be justifiably seen as following the cynical playbook of the former interim President Ranil Wickremesinghe. What is the point, it will be asked, in subjecting Ranil Wickremesinghe to police harassment over travel expenses while following his playbook in postponing elections?

Come to think of it, no VVIP anywhere can now whine of unfair police arrest after what happened to the disgraced former prince Andrew Mountbatten Windsor in England on Thursday. Good for the land where habeas corpus and due process were born. The King did not know what was happening to his kid brother, and he was wise enough to pronounce that “the law must take its course.” There is no course for the law in Trump’s America where Epstein spun his webs around rich and famous men and helpless teenage girls. Only cover up. Thanks to his Supreme Court, Trump can claim covering up to be a core function of his presidency, and therefore absolutely immune from prosecution. That is by the way.

Back to Sri Lanka, meddling with elections timing and process was the method of operations of previous governments. The NPP is supposed to change from the old ways and project a new way towards a Clean Sri Lanka built on social and ethical pillars. How does postponing elections square with the project of Clean Sri Lanka? That is the question that the government must be asking itself. The decision to hold PC elections should not be influenced by whether India is not asking for it or if Canada is requesting it.

Apart from it is the right thing do, it is also politically the smart thing to do.

The pros are aplenty for holding PC elections as soon it is practically possible for the Election Commission to hold them. Parliament can and must act to fill any legal loophole. The NPP’s political mojo is in the hustle and bustle of campaigning rather than in the sedentary business of governing. An election campaign will motivate the government to re-energize itself and reconnect with the people to regain momentum for the remainder of its term.

While it will not be possible to repeat the landslide miracle of the 2024 parliamentary election, the government can certainly hope and strive to either maintain or improve on its performance in the local government elections. The government is in a better position to test its chances now, before reaching the halfway mark of its first term in office than where it might be once past that mark.

The NPP can and must draw electoral confidence from the latest (February 2026) results of the Mood of the Nation poll conducted by Verité Research. The government should rate its chances higher than what any and all of the opposition parties would do with theirs. The Mood of the Nation is very positive not only for the NPP government but also about the way the people are thinking about the state of the country and its economy. The government’s approval rating is impressively high at 65% – up from 62% in February 2025 and way up from the lowly 24% that people thought of the Ranil-Rajapaksa government in July 2024. People’s mood is also encouragingly positive about the State of the Economy (57%, up from 35% and 28%); Economic Outlook (64%, up from 55% and 30%); the level of Satisfaction with the direction of the country( 59%, up from 46% and 17%).

These are positively encouraging numbers. Anyone familiar with North America will know that the general level of satisfaction has been abysmally low since the Iraq war and the great economic recession. The sour mood that invariably led to the election of Trump. Now the mood is sourer because of Trump and people in ever increasing numbers are looking for the light at the end of the Trump tunnel. As for Sri Lanka, the country has just come out of the 20-year long Rajapaksa-Ranil tunnel. The NPP represents the post Rajapaksa-Ranil era, and the people seem to be feeling damn good about it.

Of course, the pundits have pooh-poohed the opinion poll results. What else would you expect? You can imagine which twisted way the editorial keypads would have been pounded if the government’s approval rating had come under 50%, even 49.5%. There may have even been calls for the government to step down and get out. But the government has its approval rating at 65% – a level any government anywhere in the Trump-twisted world would be happy to exchange without tariffs. The political mood of the people is not unpalpable. Skeptical pundits and elites will have to only ask their drivers, gardeners and their retinue of domestics as to what they think of AKD, Sajith or Namal. Or they can ride a bus or take the train and check out the mood of fellow passengers. They will find Verité’s numbers are not at all far-fetched.

Confab Threats

The government’s plausible popularity and the opposition’s obvious weaknesses should be good enough reason for the government to have the PC elections sooner than later. A new election campaign will also provide the opportunity not only for the government but also for the opposition parties to push back on the looming threat of bad old communalism making a comeback. As reported last week, a “massive Sangha confab” is to be held at 2:00 PM on Friday, February 20th, at the All Ceylon Buddhist Congress Headquarters in Colombo, purportedly “to address alleged injustices among monks.”

According to a warning quote attributed to one of the organizers, Dambara Amila Thero, “never in the history of Sri Lanka has there been a government—elected by our own votes and the votes of the people—that has targeted and launched such systematic attacks against the entire Sasana as this one.” That is quite a mouthful and worthier practitioners of Buddhism have already criticized this unconvincing claim and its being the premise for a gathering of spuriously disaffected monks. It is not difficult to see the political impetus behind this confab.

The impetus obviously comes from washed up politicians who have tried every slogan from – L-board-economists, to constitutional dictatorship, to save-our children from sex-education fear mongering – to attack the NPP government and its credibility. They have not been able to stick any of that mud on the government. So, the old bandicoots are now trying to bring back the even older bogey of communalism on the pretext that the NPP government has somewhere, somehow, “targeted and launched such systematic attacks against the entire Sasana …”

By using a new election campaign to take on this threat, the government can turn the campaign into a positively educational outreach. That would be consistent with the President’s and the government’s commitment to “rebuild Sri Lanka” on the strength of national unity without allowing “division, racism, or extremism” to undermine unity. A potential election campaign that takes on the confab of extremists will also provide a forum and an opportunity for the opposition parties to let their positions known. There will of course be supporters of the confab monks, but hopefully they will be underwhelming and not overwhelming.

For all their shortcomings, Sajith Premadasa and Namal Rajapaksa belong to the same younger generation as Anura Kumara Dissanayake and they are unlikely to follow the footsteps of their fathers and fan the flames of communalism and extremism all over again. Campaigning against extremism need not and should not take the form of disparaging and deriding those who might be harbouring extremist views. Instead, the fight against extremism should be inclusive and not exclusive, should be positively educational and appeal to the broadest cross-section of people. That is the only sustainable way to fight extremism and weaken its impacts.

Provincial Councils and Reconciliation

In the framework of grand hopes and simple steps of reconciliation, provincial councils fall somewhere in between. They are part of the grand structure of the constitution but they are also usable instruments for achieving simple and practical goals. Obviously, the Northern Provincial Council assumes special significance in undertaking tasks associated with reconciliation. It is the only jurisdiction in the country where the Sri Lankan Tamils are able to mind their own business through their own representatives. All within an indivisibly united island country.

But people in the north will not be able to do anything unless there is a provincial council election and a newly elected council is established. If the NPP were to win a majority of seats in the next Northern Provincial Council that would be a historic achievement and a validation of its approach to national reconciliation. On the other hand, if the NPP fails to win a majority in the north, it will have the opportunity to demonstrate that it has the maturity to positively collaborate from the centre with a different provincial government in the north.

The Eastern Province is now home to all three ethnic groups and almost in equal proportions. Managing the Eastern Province will an experiential microcosm for managing the rest of the country. The NPP will have the opportunity to prove its mettle here – either as a governing party or as a responsible opposition party. The Central Province and the Badulla District in the Uva Province are where Malaiyaka Tamils have been able to reconstitute their citizenship credentials and exercise their voting rights with some meaningful consequence. For decades, the Malaiyaka Tamils were without voting rights. Now they can vote but there is no Council to vote for in the only province and district they predominantly leave. Is that fair?

In all the other six provinces, with the exception of the Greater Colombo Area in the Western Province and pockets of Muslim concentrations in the South, the Sinhalese predominate, and national politics is seamless with provincial politics. The overlap often leads to questions about the duplication in the PC system. Political duplication between national and provincial party organizations is real but can be avoided. But what is more important to avoid is the functional duplication between the central government in Colombo and the provincial councils. The NPP governments needs to develop a different a toolbox for dealing with the six provincial councils.

Indeed, each province regardless of the ethnic composition, has its own unique characteristics. They have long been ignored and smothered by the central bureaucracy. The provincial council system provides the framework for fostering the unique local characteristics and synthesizing them for national development. There is another dimension that could be of special relevance to the purpose of reconciliation.

And that is in the fostering of institutional partnerships and people to-people contacts between those in the North and East and those in the other Provinces. Linkages could be between schools, and between people in specific activities – such as farming, fishing and factory work. Such connections could be materialized through periodical visits, sharing of occupational challenges and experiences, and sports tournaments and ‘educational modules’ between schools. These interactions could become two-way secular pilgrimages supplementing the age old religious pilgrimages.

Historically, as Benedict Anderson discovered, secular pilgrimages have been an important part of nation building in many societies across the world. Read nation building as reconciliation in Sri Lanka. The NPP government with its grassroots prowess is well positioned to facilitate impactful secular pilgrimages. But for all that, there must be provincial councils elections first.

by Rajan Philips

Features

Barking up the wrong tree

The idiom “Barking up the wrong tree” means pursuing a mistaken line of thought, accusing the wrong person, or looking for solutions in the wrong place. It refers to hounds barking at a tree that their prey has already escaped from. This aptly describes the current misplaced blame for young people’s declining interest in religion, especially Buddhism.

It is a global phenomenon that young people are increasingly disengaged from organized religion, but this shift does not equate to total abandonment, many Gen Z and Millennials opt for individual, non-institutional spirituality over traditional structures. However, the circumstances surrounding Buddhism in Sri Lanka is an oddity compared to what goes on with religions in other countries. For example, the interest in Buddha Dhamma in the Western countries is growing, especially among the educated young. The outpouring of emotions along the 3,700 Km Peace March done by 16 Buddhist monks in USA is only one example.

There are good reasons for Gen Z and Millennials in Sri Lanka to be disinterested in Buddhism, but it is not an easy task for Baby Boomer or Baby Bust generations, those born before 1980, to grasp these bitter truths that cast doubt on tradition. The two most important reasons are: a) Sri Lankan Buddhism has drifted away from what the Buddha taught, and b) The Gen Z and Millennials tend to be more informed and better rational thinkers compared to older generations.

This is truly a tragic situation: what the Buddha taught is an advanced view of reality that is supremely suited for rational analyses, but historical circumstances have deprived the younger generations over centuries from knowing that truth. Those who are concerned about the future of Buddhism must endeavor to understand how we got here and take measures to bridge that information gap instead of trying to find fault with others. Both laity and clergy are victims of historical circumstances; but they have the power to shape the future.

First, it pays to understand how what the Buddha taught, or Dhamma, transformed into 13 plus schools of Buddhism found today. Based on eternal truths he discovered, the Buddha initiated a profound ethical and intellectual movement that fundamentally challenged the established religious, intellectual, and social structures of sixth-century BCE India. His movement represented a shift away from ritualistic, dogmatic, and hierarchical systems (Brahmanism) toward an empirical, self-reliant path focused on ethics, compassion, and liberation from suffering. When Buddhism spread to other countries, it transformed into different forms by absorbing and adopting the beliefs, rituals, and customs indigenous to such land; Buddha did not teach different truths, he taught one truth.

Sri Lankan Buddhism is not any different. There was resistance to the Buddha’s movement from Brahmins during his lifetime, but it intensified after his passing, which was responsible in part for the disappearance of Buddhism from its birthplace. Brahminism existed in Sri Lanka before the arrival of Buddhism, and the transformation of Buddhism under Brahminic influences is undeniable and it continues to date.

This transformation was additionally enabled by the significant challenges encountered by Buddhism during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (Wachissara 1961, Mirando 1985). It is sad and difficult to accept, but Buddhism nearly disappeared from the land that committed the Teaching into writing for the first time. During these tough times, with no senior monks to perform ‘upasampada,’ quasi monks who had not been admitted to the order – Ganninanses, maintained the temples. Lacking any understanding of the doctrinal aspects of Buddha’s teaching, they started performing various rituals that Buddha himself rejected (Rahula 1956, Marasinghe 1974, Gombrich 1988, 1997, Obeyesekere 2018).

The agrarian population had no way of knowing or understanding the teachings of the Buddha to realize the difference. They wanted an easy path to salvation, some power to help overcome an illness, protect crops from pests or elements; as a result, the rituals including praying and giving offerings to various deities and spirits, a Brahminic practice that Buddha rejected in no uncertain terms, became established as part of Buddhism.

This incorporation of Brahminic practices was further strengthened by the ascent of Nayakkar princes to the throne of Kandy (1739–1815) who came from the Madurai Nayak dynasty in South India. Even though they converted to Buddhism, they did not have any understanding of the Teaching; they were educated and groomed by Brahminic gurus who opposed Buddhism. However, they had no trouble promoting the beliefs and rituals that were of Brahminic origin and supporting the institution that performed them. By the time British took over, nobody had any doubts that the beliefs, myths, and rituals of the Sinhala people were genuine aspects of Buddha’s teaching. The result is that today, Sri Lankan Buddhists dare doubt the status quo.

The inclusion of Buddhist literary work as historical facts in public education during the late nineteenth century Buddhist revival did not help either. Officially compelling generations of students to believe poetic embellishments as facts gave the impression that Buddhism is a ritualistic practice based on beliefs.

This did not create any conflict in the minds of 19th agrarian society; to them, having any doubts about the tradition was an unthinkable, unforgiving act. However, modernization of society, increased access to information, and promotion of rational thinking changed things. Younger generations have begun to see the futility of current practices and distance themselves from the traditional institution. In fact, they may have never heard of it, but they are following Buddha’s advice to Kalamas, instinctively. They cannot be blamed, instead, their rational thinking must be appreciated and promoted. It is the way the Buddha’s teaching, the eternal truth, is taught and practiced that needs adjustment.

The truths that Buddha discovered are eternal, but they have been interpreted in different ways over two and a half millennia to suit the prevailing status of the society. In this age, when science is considered the standard, the truth must be viewed from that angle. There is nothing wrong or to be afraid of about it for what the Buddha taught is not only highly scientific, but it is also ahead of science in dealing with human mind. It is time to think out of the box, instead of regurgitating exegesis meant for a bygone era.

For example, the Buddhist model of human cognition presented in the formula of Five Aggregates (pancakkhanda) provides solutions to the puzzles that modern neuroscience and philosophers are grappling with. It must be recognized that this formula deals with the way in which human mind gathers and analyzes information, which is the foundation of AI revolution. If the Gen Z and Millennial were introduced to these empirical aspects of Dhamma, they would develop a genuine interest in it. They thrive in that environment. Furthermore, knowing Buddha’s teaching this way has other benefits; they would find solutions to many problems they face today.

Buddha’s teaching is a way to understand nature and the humans place in it. One who understands this can lead a happy and prosperous life. As the Dhammapada verse number 160 states – “One, indeed, is one’s own refuge. Who else could be one’s own refuge?” – such a person does not depend on praying or offering to idols or unknown higher powers for salvation, the Brahminic practice. Therefore, it is time that all involved, clergy and laity, look inwards, and have the crucial discussion on how to educate the next generation if they wish to avoid Sri Lankan Buddhism suffer the same fate it did in India.

by Geewananda Gunawardana, Ph.D.

Features

Why does the state threaten Its people with yet another anti-terror law?

The Feminist Collective for Economic Justice (FCEJ) is outraged at the scheme of law proposed by the government titled “Protection of the State from Terrorism Act” (PSTA). The draft law seeks to replace the existing repressive provisions of the Prevention of Terrorism Act 1979 (PTA) with another law of extraordinary powers. We oppose the PSTA for the reason that we stand against repressive laws, normalization of extraordinary executive power and continued militarization. Ruling by fear destroys our societies. It drives inequality, marginalization and corruption.

Our analysis of the draft PSTA is that it is worse than the PTA. It fails to justify why it is necessary in today’s context. The PSTA continues the broad and vague definition of acts of terrorism. It also dangerously expands as threatening activities of ‘encouragement’, ‘publication’ and ‘training’. The draft law proposes broad powers of arrest for the police, introduces powers of arrest to the armed forces and coast guards, and continues to recognize administrative detention. Extremely disappointing is the unjustifiable empowering of the President to make curfew order and to proscribe organizations for indefinite periods of time, the power of the Secretary to the Ministry of Defence to declare prohibited places and police officers in the rank of Deputy Inspector Generals are given the power to secure restriction orders affecting movement of citizens. The draft also introduces, knowing full well the context of laws delays, the legal perversion of empowering the Attorney General to suspend prosecution for 20 years on the condition that a suspect agrees to a form of punishment such as public apology, payment of compensation, community service, and rehabilitation. Sri Lanka does not need a law normalizing extraordinary power.

We take this moment to remind our country of the devastation caused to minoritized populations under laws such as the PTA and the continued militarization, surveillance and oppression aided by rapidly growing security legislation. There is very limited space for recovery and reconciliation post war and also barely space for low income working people to aspire to physical, emotional and financial security. The threat posed by even proposing such an oppressive law as the PSTA is an affront to feminist conceptions of human security. Security must be recognized at an individual and community level to have any meaning.

The urgent human security needs in Sri Lanka are undeniable – over 50% of households in the country are in debt, a quarter of the population are living in poverty, over 30% of households experience moderate/severe food insecurity issues, the police receive over 100,000 complaints of domestic violence each year. We are experiencing deepening inequality, growing poverty, assaults on the education and health systems of the country, tightening of the noose of austerity, the continued failure to breathe confidence and trust towards reconciliation, recovery, restitution post war, and a failure to recognize and respond to structural discrimination based on gender, race and class, religion. State security cannot be conceived or discussed without people first being safe, secure, and can hope for paths towards developing their lives without threat, violence and discrimination. One year into power and there has been no significant legislative or policy moves on addressing austerity, rolling back of repressive laws, addressing domestic and other forms of violence against women, violence associated with household debt, equality in the family, equality of representation at all levels, and the continued discrimination of the Malaiyah people.

The draft PSTA tells us that no lessons have been learnt. It tells us that this government intends to continue state tools of repression and maintain militarization. It is hard to lose hope within just a year of a new government coming into power with a significant mandate from the people to change the system, and yet we are here. For women, young people, children and working class citizens in this country everyday is a struggle, everyday is a minefield of threats and discrimination. We do not need another threat in the form of the PSTA. Withdraw the PSTA now!

The Feminist Collective for Economic Justice is a collective of feminist economists, scholars, feminist activists, university students and lawyers that came together in April 2022 to understand, analyze and give voice to policy recommendations based on lived realities in the current economic crisis in Sri Lanka.

Please send your comments to – feministcollectiveforjustice@gmail.com

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoMinistry of Brands to launch Sri Lanka’s first off-price retail destination

-

Features11 hours ago

Features11 hours agoWhy does the state threaten Its people with yet another anti-terror law?

-

Latest News2 days ago

Latest News2 days agoNew Zealand meet familiar opponents Pakistan at spin-friendly Premadasa

-

Latest News2 days ago

Latest News2 days agoTariffs ruling is major blow to Trump’s second-term agenda

-

Latest News2 days ago

Latest News2 days agoECB push back at Pakistan ‘shadow-ban’ reports ahead of Hundred auction

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoGiants in our backyard: Why Sri Lanka’s Blue Whales matter to the world

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoOld and new at the SSC, just like Pakistan

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoConstruction begins on country’s largest solar power project in Hambantota