Life style

A synthesis of native craft and European design

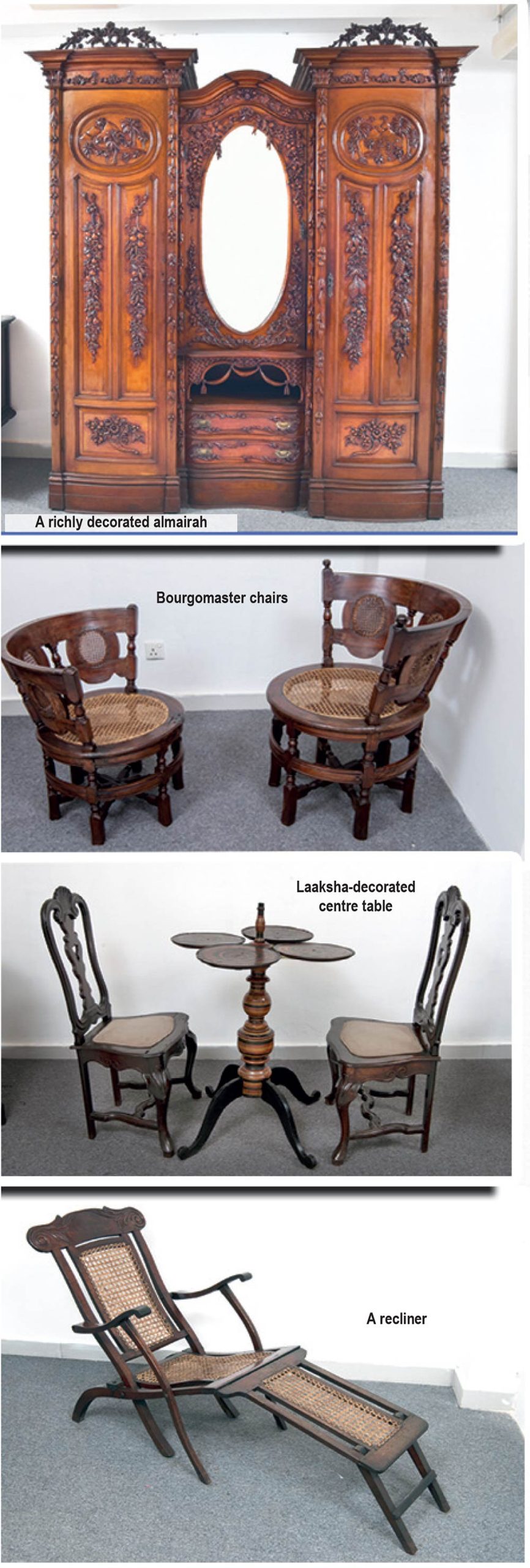

Colombo National Museum’s new Furniture Gallery which displays a fine collection from the Kandyan kingdom and the colonial times, is soon to be opened to the public. We had a sneak-peak at the new gallery’s intricately designed ebony almirahs, four-posters, palanquins from the Kandyan times, cradles and Burgomaster chairs from the Dutch times and much more…

BY RANDIMA ATTYGALLE

The first impression of the Colombo National Museum’s new Furniture Gallery is that it’s a synthesis of the indigenous craft and that of the European genus. The 17th century Dutch grandfather clock which stands tall at the entrance to the gallery is juxtaposed with the traditional Kandyan laaksha-embelished centre tables. The richly ornamented Kandyan palanquins and finely crafted chairs inspired by the Dutch tradition, equally speak for the skills of the Lankan artisan who could navigate different schools of art with ease.

A luxury of the nobility

Until the mid-20th century, the use of furniture in Lankan homes was minimal. Except for small three-legged benches, there were hardly any pieces of furniture found in ordinary households. Even guest seating was arranged by laying a mat on the outside verandah. The use of furniture was accepted as a luxury by the royalty, nobility and the priests. Ananda Coomaraswamy in his work Mediaeval Sinhalese Art notes that, ‘none but the king was allowed to sit upon a chair with a back.’ The chairs that we are familiar with today did not exist here at home in the early 16th century. Coomaraswamy further writes of a beautiful chair dedicated by Kirti Sri Raja Sinha preserved in the Asgiriya pohoya-ge which is painted and inlaid with ivory. Paintings at Degaldoruwa also depict a number of types of stools and chairs. ‘Ordinary tables, were not in general use, though mentioned by Knox (Robert Knox) among the King’s private treasures, most of which he had obtained from wrecks or were gifts brought by ambassadors,’ says Coomaraswamy.

Colonial influence

Most of the furniture we are familiar with today such as chairs, tables, bedsteads and wardrobes were first introduced to the island by the Portuguese in the 16th century. The native words putuwa and almariya (derived from the Portuguese word armario) are of Portuguese origin. Later, the Dutch colonization of the coastal areas of the island gave birth to a rich furniture-making legacy.

In the article, ‘Colonial Dutch Furniture’ by E. Reimers published in the Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society (RAS) of 1937 (Vol XXXIV), the writer states that the ‘Dutch with their characteristic caution and attention to details should have provided for their domestic needs in their Eastern colonies’ and have probably brought some of their master carpenters to the island. Local carpenters probably became their understudies.

R . L Brohier in his book, Furniture of the Dutch Period in Ceylon documents: ‘Large number of Porto-Sinhalese and others from the Sinhala community whose ancient trade was carpentering found employment in the Dutch winkels or workshops in Ceylon. It was from the Dutch that the ‘Moratuwa Carpenter’ and the Low country Sinhalese generally learnt the art of furniture-making and even up to the British period of occupation in Ceylon duplicated the genuine Dutch models and preserved many of the Dutch patterns.’

Superior Ceylonese furniture

Brohier further notes that, ‘the period which the Dutch were in Ceylon synchronized with this golden age of furniture development in Europe-claimed by authorities to have been a period of artistic activity never equaled before or since in the history of furniture.’ The assortment of chairs, settees, book cases and wardrobes found in the Colombo Museum’s new gallery is a testimony to this legacy the Dutch.

The Burgomaster chair type which was first made in the Netherlands in about 1650 and the subsequent Queen Anne Style type and those of the rococo style (which are found in the Wolvendaal Church in Colombo) are among the interesting chairs found in the gallery. Jan Veenendaal in his book, Furniture from Indonesia, Sri Lanka and India during the Dutch Period, observes the distinction between the chairs from Sri Lanka and Indonesia in the 1740s. ‘The difference between chairs from Sri Lanka and Indonesia is very marked during this period. In Sri Lanka, the Dutch style was followed more assiduously, Chinese and of course Indonesian influences on methods of ornamentation are completely absent.’ Dr. Joseph Pearson in his writing in RAS (Ceylon) Vol XXXI, 1938 makes a distinction between old Javanese and Ceylonese furniture: ‘Generally speaking, the types of old furniture in Java has characters of its own…. The furniture is frequently overloaded with rough carving and as a rule is inferior to Ceylon furniture which is dignified in style and restrained in motif.’

Clock of the last Dutch Governor

The grandfather clock in the gallery is indeed a show-stealer. Brohier in his work provides an extensive account of it. Dating back to 1710, the clock it claimed to have been the property of the last Dutch Governor of Ceylon, John Gerard van Angelbeek. Subsequently, it passed into the possession of Leslie de Saram who was a connoisseur of antiques in 1936. He then gifted it to the University of Ceylon in memory of his mother. Brohier recalls having seen this iconic article on a visit to the university in 1963 when the clock was still intoning ‘tick-tock’. This valuable antique was ‘indecorously destroyed beyond repair together with other articles of furniture in the student riots of December 1965,’ records the historian.

Local timber and art

The laaksha or traditional Sri Lankan lacquer work has a deep-rooted history. Matale is the best-known region in the island for this art. The legend has it that this art was introduced to the island with the arrival of Theri Sangamitta who brought the sapling of the sacred ‘Sri Maha Bodhi’ tree, accompanied by numerous artisans who introduced their respective traditions to the island. Ananda Coomaraswamy describes the Sinhalase lac-work to be of ‘great brilliancy and gaiety of colouring.’ He also notes that most of the work is from a decorative point of view. The laaksha-adorned centre tables found in the gallery mirror this brilliance and add colour to the place.

In the selection of material for their earliest 17th century furniture, the Dutch appear to have shown a marked preference for dark or coloured woods, mainly ebony, records E. Reimers in his contribution to RAS (Ceylon) of 1937 (Vol XXXIV). ‘We may imagine that the Hollander’s imagination ran riot when he first came out to the East and saw rich varieties of woods which the virgin forests of Ceylon and Mauritius afforded.’ Among the other local timbers sought after by the Dutch were Calamander, (which was found in the wet forests of the Southern provinces and in the wilderness of Sri Pada, recklessly felled by the Dutch and the British and is almost extinct today), Nedun, Satinwood, Tamarind, Kumbuk, Jak, Halmilla, Suriya, Kohomba and Mara.

Public participation

The soon to be opened new Furniture Gallery at the Colombo National Museum is a fine representation of the cultural intersection of Sri Lanka, says the Director General of the Department of National Museums, Sanuja Kasthuriarachchi. “The fine collection of furniture we have as exhibits ranging from the Kandyan era to the British period in the island reflects not merely the colonial influence on the furniture-making in the island but also the fact that our traditional carpenters and artisans were naturally endowed with the skill, given their long-standing association with wood crafts.

“The Kandyan Kingdom in particular is associated with an architecture and crafts dominated by wood. This inherent skill would have probably driven our carpenters of the colonial times to ably grasp the European styles,” remarks Kasthuriarachchi who invites history-lovers to enjoy the exhibits and revisit a rich tradition. “We also welcome unique articles of furniture as gifts from the public to the gallery as means of enabling a richer experience to museum visitors,” she added.

(Pic credit: Department of National Museums)

Life style

Celebration of taste, culture and elegance

Italian Cuisine Week

This year’s edition of Italian Cuisine Week in Sri Lanka unfolded with unmistakable charm, elegance and flavour as the Italian Embassy introduced a theme that captured the very soul of Italian social life ‘Apertivo and’ Stuzzichini’ This year’s celebration brought together diplomats, food lovers, chefs and Colombo’s society crowd for an evening filled with authenticity, refinement and the unmistakable charm of Italian hospitality.

Hosted at the Italian ambassador’s Residence in Colombo, the evening brought Italy’s golden hour ritual to life, embracing the warmth of Mediterranean hospitality and sophistication of Colombo social scene.

The ambience at the residence of the Italian Ambassador, effortlessly refined, evoked the timeless elegance of Milanese evening culture where ‘Apertivo’ is not just a drink , but a moment of pause, connection and pleasure. Guests were greeted with the aromas of apertivo classics and artisanal stuzzichini,curated specially for this edition. From rustic regional flavours to contemporary interpretations the embassy ‘s tables paid homage to Italy’s diverse culinary landscape.

, Italy’s small bites meant to tempt the palate before meal. Visiting Italian chefs worked alongside Colombo’s leading culinary teams to curate a menu that showcased regional authenticity though elegant bite sized creations. The Italian Ambassador of Italy in Sri Damiano Francovigh welcomed guests with heartfelt remarks on the significant of the theme, highlighting how “Apertivo”embodies the essence of Italy’s culinary identity, simple, social and rooted in tradition.

Sri Lanka’s participation in Italian Cuisine Week for ten consecutive years stands as a testament to the friendship between the two countries. This year focus on ‘Apertivo’ and ‘Stuzzichini’ added a fresh, dimension to that relationship, one that emphasised not only flavours, but shaped cultural values of hospitality, family and warmth. This year’s ‘Apertivo’ and “Stuzzichini’ theme brought a refreshing twist to Italian Cuisine Week. It reminded Sri Lankan guests t hat sometimes the most memorable culinary experiences come not from elaborate feasts but from the simplicity of serving small plates with good company.

Italian Cuisine Week 2025 in Sri Lanka may have showcased flavours, but more importantly it showcased connection and in the warm glow of Colombo’s evening Apertivo came alive not just as an Italian tradition.

(Pix by Dharmasena Wellipitiya)

By Zanita Careem

The Week of Italian Cuisine in the World is one of the longest-running thematic reviews promoted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation. Founded in 2016 to carry forward the themes of Expo Milano 2015—quality, sustainability, food

safety, territory, biodiversity, identity, and education—the event annually showcases the excellence and global reach of Italy’s food and wine sector.

Since its inauguration, the Week has been celebrated with over 10,000 events in more than 100 countries, ranging from tastings, show cooking and masterclasses to seminars, conferences, exhibitions and business events, with a major inaugural event hosted annually in Rome at the Farnesina, the HQ of the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation.

The 10th edition of the Italian Cuisine Week in the World.

In 2025, the Italian Cuisine Week in the World reaches its tenth edition.

The theme chosen for this anniversary is “Italian cuisine between culture, health and innovation.”

This edition highlights Italian cuisine as a mosaic of knowledge and values, where each tile reflects a story about the relationship with food.

The initiatives of the 10th Edition aim to:

promote understanding of Italian cuisine, also in the context of its candidacy for UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage;

demonstrate how Italian cuisine represents a healthy, balanced, and sustainable food model, supporting the prevention of non-communicable diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases and diabetes;

emphasize the innovation and research that characterize every stage of the Italian food chain, from production to processing, packaging, distribution, consumption, reuse, and recycling

The following leading hotels in Colombo Amari Colombo, Cinnamon Life, ITC Ratnadipa and The Kingsbury join in the celebration by hosting Italian chefs throughout the Week.

- Jesudas, chef Collavini,Travis Casather and Mahinda Wijeratne

- Barbara Troila and Italian Ambassador Damiano F rancovigh

- Janaka Fonseka and Rasika Fonseka

- Mayor Balthazar and Ambassador of Vietnam,Trinh Thi Tam

- Anika Williamson

- Alberto Arcidiacono and Amber Dhabalia

- Thrilakshi Gaveesha

- Dasantha Fonseka and Kumari Fonseka

Life style

Ethical beauty takes centre stage

The Body Shop marked a radiant new chapter in Sri Lanka with the opening of its boutique at One Galle Face Mall, an event that blended conscious beauty, festive sparkle and lifestyle elegance. British born and globally loved beauty brand celebrates ten successful years in Sri lanka with the launch of its new store at the One Galle Face Mall. The event carried an added touch of prestige as the British High Commissioner Andrew Patrick to Sri Lanka attended as the Guest of honour.

His participation elevated the event highlighting the brand’s global influence and underscored the strong UK- Sri Lanka connection behind the Body Shop’s global heritage and ethical values.

Celebrating ten years of the Brand’s presence in the country, the launch became a true milestone in Colombo’s evolving beauty landscape.

Also present were the Body Shop Sri Lanka Director, Kosala Rohana Wickramasinghe, Shriti malhotra, Executive chairperson,Quest Retail.The Body shop South Asia and Vishal Chaturvedi , Chief Revenue Officer-The Body South Asia The boutique showcased the brand’s

complete range from refreshing Tea Tree skin care to the iconic body butters to hair care essentials each product enhancing the Body Shop’s values of cruelty ,fair trade formulation, fair trade ingredients and environmentally mindful packaging.

The store opening also unveiled the much anticipated festive season collection.

With its elegant atmosphere, engaging product experiences and the distinguished present of the British High Commissioner, it was an evening that blended glamour with conscience With its fresh inviting space at Colombo’ premier mall, the Body Shop begins a a new decade of inspiring Sri Lankan consumers to choose greener beauty.

Life style

Ladies’ Night lights up Riyadh

The Cultural Forum of Sri Lanka in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia brought back Ladies’ Night 2025 on November 7 at the Holiday Inn Al Qasr Hotel. After a hiatus of thirteen years, Riyadh shimmered once again as Ladies’ Night returned – an elegant celebration revived under the chairperson Manel Gamage and her team. The chief guest for the occasion was Azmiya Ameer Ajwad, spouse of the Ambassador of Sri Lanka to K. S. A. There were other dignitaries too.

The Cultural Forum of Sri Lanka in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia brought back Ladies’ Night 2025 on November 7 at the Holiday Inn Al Qasr Hotel. After a hiatus of thirteen years, Riyadh shimmered once again as Ladies’ Night returned – an elegant celebration revived under the chairperson Manel Gamage and her team. The chief guest for the occasion was Azmiya Ameer Ajwad, spouse of the Ambassador of Sri Lanka to K. S. A. There were other dignitaries too.

The show stopper was Lisara Fernando finalist from the voice Sri Lankan Seasons, wowed the crowd with her stunning performances. The excitement continued with a lively beauty pageant, where Ilham Shamara Azhar was crowned the beauty queen of the night. Thanks to a thrilling raffle draw, many lucky guests walked away with fabulous prizes, courtesy of generous sponsors.

The evening unfolded with a sense of renewal, empowerment and refined glamour drawing together the women for a night that was both historic and beautifully intimate. From dazzling couture to modern abayas, from soft light installation to curated entertainment, the night carried the unmistakable energy.

Once a cherished annual tradition, Ladies’ Night had long held a special space in Riyadh’s cultural calendar. But due to Covid this event was not held until this year in November. This year it started with a bang. After years Ladies’ Night returned bringing with a burst of colour, confidence and long-awaited camaraderie.

It became a symbol of renewal. This year began with a vibrant surge of energy. The decor blended soft elegance with modern modernity cascading its warm ambient lighting and shimmering accents that turned the venue into a chic, feminine oasis, curated by Shamila Abusally, Praveen Jayasinghe and Hasani Weerarathne setting the perfect atmosphere while compères Rashmi Fernando and Gayan Wijeratne kept the energy high and kept the guests on their toes making the night feel intimate yet grand.

Conversations flowed as freely as laughter. Women from different backgrounds, nationalities and professions came together united by an unspoken bond of joy and renewal. Ladies’ Night reflected a broader narrative of change. Riyadh today is confidently evolving and culturally dynamic.

The event celebrated was honouring traditions while empowering international flair.

As the night drew to a close, there was a shared sense that this event was only the beginning. The applause, the smiles, the sparkles in the air, all hinted at an event that is set to redeem its annual place with renewed purpose in the future. Manel Gamage and her team’s Ladies’ Night in Riyadh became more than a social occasion. It became an emblem of elegance, and reflected a vibrant new chapter of Saudi Arabia’s capital.

Thanks to Nihal Gamage and Nirone Disanayake, too, Ladies’ night proved to be more than event,it was a triumphant celebration of community, culture and an unstoppable spirit of Sr Lankan women in Riyadh

In every smile shared every dance step taken and every moment owned unapologetically Sr Lankan women in Riyadh continue to show unstoppable. Ladies’ Night is simply the spotlight that will shine forever .This night proved to be more than an event, it was a triumphant celebration of community, culture and the unstoppable spirit of Sri Lankan women in Riyadh.

In every smile shared, every dance steps taken and every moment owned unapologetically Sri Lankan women in Riyadh continue to show that their spirit is unstoppable. Ladies’ Night was simply the spotlight and the night closed on a note of pride!

- Evening glamour

- Different backgrounds, one unforgettable evening

- Shamila lighting traditional oil lamp while chief guest Azmiya looks on

- Unity in diversity

- capturing the spirit of the evening

- Radiant smiles stole the spotlight

- Every nationality added its own colour and charm

- Elegance personified

- Crowning the beauty queen

- Chairperson Manel Gamage welcoming guests

- Captivating performances

- Royal moment of poise and power

- Elegance and style in every form

-

News6 days ago

Lunuwila tragedy not caused by those videoing Bell 212: SLAF

-

News13 hours ago

News13 hours agoOver 35,000 drug offenders nabbed in 36 days

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoLevel III landslide early warning continue to be in force in the districts of Kandy, Kegalle, Kurunegala and Matale

-

Latest News7 days ago

Latest News7 days agoLevel III landslide early warnings issued to the districts of Badulla, Kandy, Kegalle, Kurunegala, Matale and Nuwara-Eliya

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoDitwah: An unusual cyclone

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoLOLC Finance Factoring powers business growth

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoCPC delegation meets JVP for talks on disaster response

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoA 6th Year Accolade: The Eternal Opulence of My Fair Lady