Midweek Review

The rise of the Bonapartists:

A political history of post-1977 Sri Lanka (Part I)

By Uditha Devapriya

Viewed in retrospect, the yahapalanaya regime seems almost a bad memory now, best forgotten. This is not to underrate its achievements, for the UNP-SLFP Unity Government did achieve certain things, like the Right to Information Act. It soon found out, however, that it couldn’t shield itself from its own reforms; that’s how 2015 led to 2019. Despite its laudable commitment to democratic rule, the yahapalanists reckoned without the popularity of the man they ousted at the ballot box. November 2019, in that sense, was a classic example of a populist resurrection, unparalleled in South Asia, though not in Asia: a government touting a neoliberal line giving way to a centre-right populist-personalist.

What went wrong with the yahapalanist experiment? Its fundamental error was its inability to think straight: the moment Maithripala Sirisena reinforced his power by wresting control of the SLFP from Mahinda Rajapaksa, he ceded space to the Joint Opposition.

Roughly, the same thing happened to the C. P. de Silva faction in 1970: after five years in power, it yielded to the same forces it had overthrown from its own party. The lesson de Silva learnt and the yahapalanists so far haven’t was that no progressive centre-left party can jettison its leftist faction while getting into a coalition with a rightwing monolith without having its credentials questioned at the ballot box. When voters responded by electing the leftist faction in 1970, the leader of the rightwing coalition, the UNP, faced electoral defeat. Dudley Senanayake had to step down, just as Ranil Wickremesinghe had to.

Deceptively conclusive as comparisons between 1970 and 2020 may be, however, there is an important distinction to make. The rightwing ideology the UNP under Dudley Senanayake, adhered to was qualitatively different to the rightwing ideology Senanayake’s successor J. R. Jayewardene embraced. The two Senanayakes, Jayewardene, and John Kotelawala lived and had been brought up in the shadow of the British Empire. Upon coming to power they oversaw a shift in their party ideology from Whitehall to Washington; this process reached its climax in the McCarthyist Kotelawala administration.

Deceptively conclusive as comparisons between 1970 and 2020 may be, however, there is an important distinction to make. The rightwing ideology the UNP under Dudley Senanayake, adhered to was qualitatively different to the rightwing ideology Senanayake’s successor J. R. Jayewardene embraced. The two Senanayakes, Jayewardene, and John Kotelawala lived and had been brought up in the shadow of the British Empire. Upon coming to power they oversaw a shift in their party ideology from Whitehall to Washington; this process reached its climax in the McCarthyist Kotelawala administration.

Jayewardene was the last of the Old Right leaders whose fortunes were tied directly to the plantation economy and whose ideology cohered with the Bretton Woods Keynesian Right of Richard Nixon and Ted Heath. The paradox at the heart of his presidency, and the shift to populism at the hands of his successors, has much to do with the transition from this Old Right to a New Right. I begin my two-part essay with that transition.

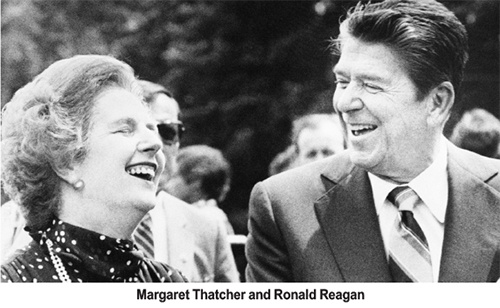

The New Right, or the neoliberal Right, came into prominence via the election of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher on either side of the Atlantic. These two figures eschewed not only the leftist opposition, but also predecessors from their own parties; Ted Heath remained to the Left of Thatcher, for instance, while Gerald Ford criticised certain parts of Reagan’s reform programme (though eventually he extended his support).

In the industrialised economies of the West, to put it succinctly, the Old Right adhered as much to price controls, quantitative easing, and economic stimulus as did their rivals on the Left. By contrast, the New Right preferred low inflation even at the cost of full employment, the elimination of subsidies, and privatisation. Readers’ Digest called David Stockman “David the Budget Killer.” The epithet was not unjustified: at the Office of Management and Budget where he served as President during the first Reagan administration, Stockman oversaw the biggest rollback of the US state since the New Deal. Nixon famously claimed that we were all Keynesians, but Reagan enthroned monetarism. So did Thatcher.

How did that spill over to underdeveloped economies, particularly non-industrialised ones such as Sri Lanka’s? In the aftermath of the 1973 oil crisis, much of the Non-Aligned non-West suffered a full decade of unprecedented calamity in the form of famines, shortages, and inefficient, unresponsive bureaucracies. The governments of many of these countries opted for state-led industrialisation, which coupled with stagflation and incomplete land reforms at home failed to deliver on what it pledged and promised.

Indeed, laudable as Sirimavo Bandaranaike’s reforms were, they became mired in their own contradictions: as S. B. D. de Silva observed, they entrenched a class of intermediaries who benefited from the regime’s economic programme. “Nothing came out of [its] attempt to industrialise,” he recounted in his last interview in 2017, “because the industrialisation was really foreign exchange driven.” In other words, embedded in it were the seeds of its own electoral destruction, a fate accelerated by the jettisoning of the Left in 1975.

The transition from the Old to the New Right in the West led to the growth of finance capital, the deindustrialisation of Western economies and the shift to Free Trade Zones in the global periphery, and the enforcement of structural adjustment vis-à-vis the IMF, the latter revolving around four principles: economic stabilisation, liberalisation, deregulation, and privatisation (Thomson, Kentikelenis, and Stubbs 2017).

Between 1970 and 1980, debt levels in Latin America alone rose by over a thousand percent. Structural adjustment, at the time lacking the kind of critique evolved by the likes of Joseph Stiglitz and Thomas Piketty later, promised a way out of indebtedness which would lead to growth, development, low inflation, and free trade. The flip-side to these benefits, which its champions left out of the discussion, was widespread poverty, a widening income gap, high unemployment, and trade practices slanted and tilted heavily to the West.

Not unlike the World Bank prescription that preceded it, structural adjustment favoured the dismantling of local industry. But where the World Bank had prescribed the establishment of small cottage industries and continued emphasis on agriculture, the IMF recommended the privatisation of local industry AND agriculture to multinational corporations. This was in keeping with the new monetarist philosophy: reduce the money supply, lower marginal tax rates, maintain a minimal social safety net, and welcome the robber barons.

The East Asian economies grew against a different backdrop. Multinational companies until then were largely, if at all, limited to Central and Latin America: the United Fruit economies. In essence, the IMF and World Bank repackaged the United Fruit model and introduced it to countries newly embracing neoliberalism. Among these was Sri Lanka.

The East Asian economies grew against a different backdrop. Multinational companies until then were largely, if at all, limited to Central and Latin America: the United Fruit economies. In essence, the IMF and World Bank repackaged the United Fruit model and introduced it to countries newly embracing neoliberalism. Among these was Sri Lanka.

In a critique of Mangala Samaraweera’s maiden Budget Speech in 2017, Dayan Jayatilleka pointed out that inasmuch as the J. R. Jayewardene administration enacted open economic reforms, it did so within the framework of a centralised state. Therein lies a paradox I earlier alluded to of the Jayewardene presidency and, to an extent, of the Premadasa presidency: the dismantling of the economy did not follow from a dismantling of the state.

Yet this differed very little from what was happening in other countries enacting structural adjustment packages: economic liberalisation took place under the watch of a centralised, authoritarian state. Much of the reason for this has to do with the contradiction at the heart of structural adjustment itself: while it freed the economy, it shackled the majority, and to keep them from rising up in protest, it had to shackle dissent too.

It’s no cause for wonder, then, that many of the leaders of countries who would oversee the transition from state-led industrialisation to “export-oriented” MNC driven growth hailed from the Old Right. Jayewardene was no exception: an eloquent, shrewd populist, he made overtures to a virtuous society while entrenching a merchant class of robber barons.

Meanwhile, the rise of a civil society posing as an alternative to the private and the public sectors, but in reality aligned with the private sector, made it no longer possible for radical scholars, educated in the West, to get involved in policy implementation with the state. As Vinod Moonesinghe has noted in a paper on relations between civil society and government (“Civil society – government relations in Sri Lanka”), after 1983 there came about a steep rise in NGO numbers. Susantha Goonetilake (Recolonisation) has argued that the structures and relationships of power within and the activities of these enclaves came to reflect those of a private organisation more than of an institution affiliated to civil society.

In stark contrast to its earlier position of engagement with the public sector, civil society stood apart and aloof from the latter, inadvertently breaking away from its historical task of getting involved at the grassroots level in policy formulation and implementation. Ironically this served to speed up the government’s delinking from civil society: enmeshed in the private sector, NGOs ended up spouting postmodernist and post-Marxist rhetoric, offering no viable alternative to the UNP’s development paradigm.

Even more ironically, what that led to was a situation where, at the height of the second JVP insurrection, their most ubiquitous representatives took the side of the government over the rebels while taking the side of Tamil separatists over the government: a paradox, given that both groups were fighting the state over class as much as over ethnicity. The NGOs’ selective treatment of the JVP and the LTTE justifies the view that in the 1980s, ethnicity replaced class as the dominant topic of discussion by social scientists.

All this undoubtedly contributed to the separation of the state from the public sphere: a prerequisite of structural adjustment and economic liberalisation. Yet paradoxically, while that process of separation went ahead, it required as a lever an autocrat who could, and would, crack down on trade unions, appease a growing petty bourgeoisie and middle class, and in contradiction to the principles of nonalignment, ally with the West. This meant couching everything domestic in Cold War terms and slanting it to an anti-Marxist position: not for no reason, after all, did Jayewardene refer to the LTTE as a group of rebels fighting to establish a Marxist state in a BBC interview. Appeasing the middle-class with these methods was easy because the middle-class faced a dilemma: while it bemoaned the government’s authoritarianism, it was in no mood to revert to the autarkyism of the Bandaranaike era. It wanted more representation, while keeping the economy open.

At the heart of middle-class support for the Jayewardene presidencies, however, lay a fatal time bomb: its Buddhist constituency. When Jayewardene, in 1982, authorised the writing of a continuation of the Mahavamsa, he reaffirmed his regime’s commitment to a Buddhist polity. In an essay on the Jathika Chintanaya, Nirmal Ranjith Dewasiri argued that while in one way 1977 appeared to be “a symbolic marker of a new epoch”, in another it betrayed “a loss of something that is Sinhala Buddhist.” Supplementing this was the rift at the heart of J. R.’s reforms: political authoritarianism versus economic liberalisation. Both were viewed as betrayals of Buddhism, quoting Stanley Tambiah’s book; dharmista samajayak, after all, was as much the winning promise of Jayewardene’s campaign as it was the title of Ediriweera Sarachchandra’s critique of his regime’s breach of that promise.

The suburban Sinhala middle bourgeoisie of artists, artisans, and professionals responded lukewarmly to Jayewardene. The results of the 1989 election confirmed the scepticism with which they viewed the achievements and failures of his administration: more than 46% of the UNP’s votes came from a third of the country’s electorate, none of which comprised Colombo’s suburbs (except for the city and the Catholic belt to the north of Colombo), while 38% of the SLFP’s votes came from, inter alia, those suburbs. The new UNP candidate they viewed cynically; “they were not convinced that Premadasa represented adequate change” (Samarasinghe 1989). The SLFP’s popularity among state employees, in particular, showed when it won 49.5% of the postal vote. A crucial litmus test for Premadasa would therefore be how his presidency would be viewed by the Sinhala Buddhist middle-class.

To be continued next week…

(The writer can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com)

Midweek Review

Rajiva on Batalanda controversy, govt.’s failure in Geneva and other matters

Former President Ranil Wickremesinghe’s recent interview with Mehdi Hasan on Al Jazeera’s ‘Head-to-Head’ series has caused controversy, both in and outside Parliament, over the role played by Wickremesinghe in the counter-insurgency campaign in the late’80s.

The National People’s Power (NPP) seeking to exploit the developing story to its advantage has ended up with egg on its face as the ruling party couldn’t disassociate from the violent past of the JVP. The debate on the damning Presidential Commission report on Batalanda, on April 10, will remind the country of the atrocities perpetrated not only by the UNP, but as well as by the JVP.

The Island sought the views of former outspoken parliamentarian and one-time head of the Government Secretariat for Coordinating the Peace Process (SCOPP) Prof. Rajiva Wijesinha on a range of issues, with the focus on Batalanda and the failure on the part of the war-winning country to counter unsubstantiated war crimes accusations.

Q:

The former President and UNP leader Ranil Wickremesinghe’s interview with Al Jazeera exposed the pathetic failure on the part of Sri Lanka to address war crimes accusations and accountability issues. In the face of aggressive interviewer Mehdi Hasan on ‘Head-to-Head,’ Wickremesinghe struggled pathetically to counter unsubstantiated accusations. Six-time Premier Wickremesinghe who also served as President (July 2022-Sept. 2024) seemed incapable of defending the war-winning armed forces. However, the situation wouldn’t have deteriorated to such an extent if President Mahinda Rajapaksa, who gave resolute political leadership during that war, ensured a proper defence of our armed forces in its aftermath as well-choreographed LTTE supporters were well in place, with Western backing, to distort and tarnish that victory completely. As wartime Secretary General of the Government’s Secretariat for Coordinating the Peace Process (since June 2007 till the successful conclusion of the war) and Secretary to the Ministry of Disaster Management and Human Rights (since Jun 2008) what do you think of Wickremesinghe’s performance?

A:

It made him look very foolish, but this is not surprising since he has no proper answers for most of the questions put to him. Least surprising was his performance with regard to the forces, since for years he was part of the assault forces on the successful Army, and expecting him to defend them is like asking a fox to stand guard on chickens.

Q:

In spite of trying to overwhelm Wickremesinghe before a definitely pro-LTTE audience at London’s Conway Hall, Hasan further exposed the hatchet job he was doing by never referring to the fact that the UNP leader, in his capacity as the Yahapalana Premier, co-sponsored the treacherous Geneva Resolution in Oc., 2015, against one’s own victorious armed forces. Hasan, Wickremesinghe and three panelists, namely Frances Harrison, former BBC-Sri Lanka correspondent, Director of International Truth and Justice Project and author of ‘Still Counting the Dead: Survivors of Sri Lanka’s Hidden War,’ Dr. Madura Rasaratnam, Executive Director of PEARL (People for Equality and Relief in Lanka) and former UK and EU MP and Wickremesinghe’s presidential envoy, Niranjan Joseph de Silva Deva Aditya, never even once referred to India’s accountability during the programme recorded in late February but released in March. As a UPFA MP (2010-2015) in addition to have served as Peace Secretariat Chief and Secretary to the Disaster Management and Human Rights Ministry, could we discuss the issues at hand leaving India out?

A:

I would not call the interview a hatchet job since Hasan was basically concerned about Wickremesinghe’s woeful record with regard to human rights. In raising his despicable conduct under Jayewardene, Hasan clearly saw continuity, and Wickremesinghe laid himself open to this in that he nailed his colours to the Rajapaksa mast in order to become President, thus making it impossible for him to revert to his previous stance. Sadly, given how incompetent both Wickremesinghe and Rajapaksa were about defending the forces, one cannot expect foreigners to distinguish between them.

Q:

You are one of the many UPFA MPs who backed Maithripala Sirisena’s candidature at the 2015 presidential election. The Sirisena-Wickremesinghe duo perpetrated the despicable act of backing the Geneva Resolution against our armed forces and they should be held responsible for that. Having thrown your weight behind the campaign to defeat Mahinda Rajapaksa’s bid to secure a third term, did you feel betrayed by the Geneva Resolution? And if so, what should have the Yahapalana administration done?

A:

By 2014, given the total failure of the Rajapaksas to deal firmly with critiques of our forces, resolutions against us had started and were getting stronger every year. Mahinda Rajapaksa laid us open by sacking Dayan Jayatilleke who had built up a large majority to support our victory against the Tigers, and appointed someone who intrigued with the Americans. He failed to fulfil his commitments with regard to reforms and reconciliation, and allowed for wholesale plundering, so that I have no regrets about working against him at the 2015 election. But I did not expect Wickremesinghe and his cohorts to plunder, too, and ignore the Sirisena manifesto, which is why I parted company with the Yahapalanaya administration, within a couple of months.

I had expected a Sirisena administration to pursue some of the policies associated with the SLFP, but he was a fool and his mentor Chandrika was concerned only with revenge on the Rajapaksas. You cannot talk about betrayal when there was no faith in the first place. But I also blame the Rajapaksas for messing up the August election by attacking Sirisena and driving him further into Ranil’s arms, so that he was a pawn in his hands.

Q:

Have you advised President Mahinda Rajapaksa’s government how to counter unsubstantiated war crimes allegations propagated by various interested parties, particularly the UN, on the basis of the Panel of Experts (PoE) report released in March 2011? Did the government accept your suggestions/recommendations?

A:

Prof. Rajiva Wijesinha

I kept trying, but Mahinda was not interested at all, and had no idea about how to conduct international relations. Sadly, his Foreign Minister was hanging around behind Namal, and proved incapable of independent thought, in his anxiety to gain further promotion. And given that I was about the only person the international community, that was not prejudiced, took seriously – I refer to the ICRC and the Japanese with whom I continued to work, and, indeed, the Americans, until the Ambassador was bullied by her doctrinaire political affairs officer into active undermining of the Rajapaksas – there was much jealousy, so I was shut out from any influence.

But even the admirable effort, headed by Godfrey Gunatilleke, was not properly used. Mahinda Rajapaksa seemed to me more concerned with providing joy rides for people rather than serious counter measures, and representation in Geneva turned into a joke, with him even undermining Tamara Kunanayagam, who, when he supported her, scored a significant victory against the Americans, in September 2011. The Ambassador, who had been intriguing with her predecessor, then told her they would get us in March, and with a little help from their friends here, they succeeded.

Q:

As the writer pointed out in his comment on Wickremesinghe’s controversial Al Jazeera interview, the former Commander-in-Chief failed to mention critically important matters that could have countered Hasan’ s line of questioning meant to humiliate Sri Lanka?

A:

How could you have expected that, since his primary concern has always been himself, not the country, let alone the armed forces?

Q:

Do you agree that Western powers and an influential section of the international media cannot stomach Sri Lanka’s triumph over separatist Tamil terrorism?

A:

There was opposition to our victory from the start, but this was strengthened by the failure to move on reconciliation, creating the impression that the victory against the Tigers was seen by the government as a victory against Tamils. The failure of the Foreign Ministry to work with journalists was lamentable, and the few exceptions – for instance the admirable Vadivel Krishnamoorthy in Chennai or Sashikala Premawardhane in Canberra – received no support at all from the Ministry establishment.

Q:

A couple of months after the 2019 presidential election, Gotabaya Rajapaksa declared his intention to withdraw from the Geneva process. On behalf of Sri Lanka that announcement was made in Geneva by the then Foreign Minister Dinesh Gunawardena, who became the Premier during Wickremesinghe’s tenure as the President. That declaration was meant to hoodwink the Sinhala community and didn’t alter the Geneva process and even today the project is continuing. As a person who had been closely involved in the overall government response to terrorism and related matters, how do you view the measures taken during Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s short presidency to counter Geneva?

A:

What measures? I am reminded of the idiocy of the responses to the Darusman report by Basil and Gotabaya Rajapaksa, who went on ego trips and produced unreadable volumes trying to get credit for themselves as to issues of little interest to the world. They were planned in response to Darusman, but when I told Gotabaya that his effort was just a narrative of action, he said that responding to Darusman was not his intention. When I said that was necessary, he told me he had asked Chief-of-Staff Roshan Goonetilleke to do that, but Roshan said he had not been asked and had not been given any resources.

My own two short booklets which took the Darusman allegations to pieces were completely ignored by the Foreign Ministry.

Q:

Against the backdrop of the Geneva betrayal in 2015 that involved the late Minister Mangala Samaraweera, how do you view President Wickremesinghe’s response to the Geneva threat?

A: Wickremesinghe did not see Geneva as a threat at all. Who exactly is to blame for the hardening of the resolution, after our Ambassador’s efforts to moderate it, will require a straightforward narrative from the Ambassador, Ravinatha Ariyasinha, who felt badly let down by his superiors. Geneva should not be seen as a threat, since as we have seen follow through is minimal, but we should rather see it as an opportunity to put our own house in order.

Q:

President Anura Kumara Dissanayake recently questioned both the loyalty and professionalism of our armed forces credited with defeating Northern and Southern terrorism. There hadn’t been a previous occasion, a President or a Premier, under any circumstances, questioned the armed forces’ loyalty or professionalism. We cannot also forget the fact that President Dissanayake is the leader of the once proscribed JVP responsible for death and destruction during 1971 and 1987-1990 terror campaigns. Let us know of your opinion on President Dissanayake’s contentious comments on the armed forces?

A: I do not see them as contentious, I think what is seen as generalizations was critiques of elements in the forces. There have been problems, as we saw from the very different approach of Sarath Fonseka and Daya Ratnayake, with regard to civilian casualties, the latter having planned a campaign in the East which led to hardly any civilian deaths. But having monitored every day, while I headed the Peace Secretariat, all allegations, and obtained explanations of what happened from the forces, I could have proved that they were more disciplined than other forces in similar circumstances.

The violence of the JVP and the LTTE and other such groups was met with violence, but the forces observed some rules which I believe the police, much more ruthlessly politicized by Jayewardene, failed to do. The difference in behaviour between the squads led for instance by Gamini Hettiarachchi and Ronnie Goonesinghe makes this clear.

Q:

Mehdi Hasan also strenuously questioned Wickremesinghe on his role in the UNP’s counter-terror campaign during the 1987-1990 period. The British-American journalists of Indian origins attacked Wickremesinghe over the Batalanda Commission report that had dealt with extra-judicial operations carried out by police, acting on the political leadership given by Wickremesinghe. What is your position?

A:

Wickremesinghe’s use of thugs’ right through his political career is well known. I still recall my disappointment, having thought better of him, when a senior member of the UNP, who disapproved thoroughly of what Jayewardene had done to his party, told me that Wickremesinghe was not honest because he used thugs. In ‘My Fair Lady,’ the heroine talks about someone to whom gin was mother’s milk, and for Wickremesinghe violence is mother’s milk, as can be seen by the horrors he associated with.

The latest revelations about Deshabandu Tennakoon, whom he appointed IGP despite his record, makes clear his approval for extra-judicial operations.

Q:

Finally, will you explain how to counter war crimes accusations as well as allegations with regard to the counter-terror campaign in the’80s?

A:

I do not think it is possible to counter allegations about the counter-terror campaign of the eighties, since many of those allegations, starting with the Welikada Prison massacre, which Wickremesinghe’s father admitted to me the government had engendered, are quite accurate. And I should stress that the worst excesses, such as the torture and murder of Wijeyedasa Liyanaarachchi, happened under Jayewardene, since there is a tendency amongst the elite to blame Premadasa. He, to give him his due, was genuine about a ceasefire, which the JVP ignored, foolishly in my view though they may have had doubts about Ranjan Wijeratne’s bona fides.

With regard to war crimes accusations, I have shown how, in my ‘Hard Talk’ interview, which you failed to mention in describing Wickeremesinghe’s failure to respond coherently to Hasan. The speeches Dayan Jayatilleke and I made in Geneva make clear what needed and still needs to be done, but clear sighted arguments based on a moral perspective that is more focused than the meanderings, and the frequent hypocrisy, of critics will not now be easy for the country to furnish.

By Shamindra Ferdinando

Midweek Review

Research: Understanding the basics and getting started – Part I

Introduction

No human civilization—whether large or small, modern or traditional—has ever survived without collectively engaging in three fundamental processes: the production and distribution of goods and services, the generation and dissemination of knowledge and culture, and the reproduction and sustenance of human life. These interconnected functions form the backbone of collective existence, ensuring material survival, intellectual continuity, and biological renewal. While the ways in which these functions are organised vary according to technological conditions, politico-economic structures and geo-climatic contexts, their indispensability remains unchanged. In the modern era, research has become the institutionalized authority in knowledge production. It serves as the primary mechanism through which knowledge is generated, rooted in systematic inquiry, methodological rigor, and empirical validation. This article examines the key aspects of knowledge formation through research, highlighting its epistemological foundations and the systematic steps involved.

What is knowledge?

Knowledge, at its core, emerged from humanity’s attempt to understand itself and its surroundings. The word “knowledge” is a noun derived from the verb “knows.” When we seek to know something, the result is knowledge—an ongoing, continuous process. However, those who seek to monopolise knowledge as a tool of authority often attribute exclusivity or even divinity to it. When the process of knowing becomes entangled with power structures and political authority, the construction of knowledge risks distortion. It is a different story.

Why do we seek to understand human beings and our environment? At its core, this pursuit arises from the reality that everything is in a state of change. People observe change in their surroundings, in society, and within themselves. Yet, the reasons behind these transformations are not always clear. Modern science explains change through the concept of motion, governed by specific laws, while Buddhism conceptualises it as impermanence (Anicca)—a fundamental characteristic of existence. Thus, knowledge evolves from humanity’s pursuit to understand the many dimensions of change

It is observed that Change is neither random nor entirely haphazard; it follows an underlying rhythm and order over time. Just as nature’s cycles, social evolution, and personal growth unfold in patterns, they can be observed and understood. Through inquiry and observation, humans can recognise these rhythms, allowing them to adapt, innovate, and find meaning in an ever-changing world. By exploring change—both scientifically and philosophically—we not only expand our knowledge but also cultivate the wisdom to navigate life with awareness and purpose.

How is Knowledge Created?

The creation of knowledge has long been regarded as a structured and methodical process, deeply rooted in philosophical traditions and intellectual inquiry. From ancient civilizations to modern epistemology, knowledge generation has evolved through systematic approaches, critical analysis, and logical reasoning.

All early civilizations, including the Chinese, Arab, and Greek traditions, placed significant emphasis on logic and structured methodologies for acquiring and expanding knowledge. Each of these civilizations contributed unique perspectives and techniques that have shaped contemporary understanding. Chinese tradition emphasised balance, harmony, and dialectical reasoning, particularly through Confucian and Taoist frameworks of knowledge formation. The Arab tradition, rooted in empirical observation and logical deduction, played a pivotal role in shaping scientific methods during the Islamic Golden Age. Meanwhile, the Greek tradition advanced structured reasoning through Socratic dialogue, Aristotelian logic, and Platonic idealism, forming the foundation of Western epistemology.

Ancient Indian philosophical traditions employed four primary strategies for the systematic creation of knowledge: Contemplation (Deep reflection and meditation to attain insights and wisdom); Retrospection (Examination of past experiences, historical events, and prior knowledge to derive lessons and patterns); Debate (Intellectual discourse and dialectical reasoning to test and refine ideas) and; Logical Reasoning (Systematic analysis and structured argumentation to establish coherence and validity).The pursuit of knowledge has always been a dynamic and evolving process. The philosophical traditions of ancient civilizations demonstrate that knowledge is not merely acquired but constructed.

Research and Knowledge

In the modern era, research gradually became the dominant mode of knowledge acquisition, shaping intellectual discourse and scientific progress. The structured framework of rules, methods, and approaches governing research ensures reliability, validity, and objectivity. This methodological rigor evolved alongside modern science, which institutionalized research as the primary mechanism for generating new knowledge.

The rise of modern science established the authority and legitimacy of research by emphasizing empirical evidence, systematic inquiry, and critical analysis. The scientific revolution and subsequent advancements across various disciplines reinforced the notion that knowledge must be verifiable and reproducible. As a result, research became not just a tool for discovery, but also a benchmark for evaluating truth claims across diverse fields. Today, research remains the cornerstone of intellectual progress, continually expanding human understanding and serving as a primary tool for the formation of new knowledge.

Research is a systematic inquiry aimed at acquiring new knowledge or enhancing existing knowledge. It involves specific methodologies tailored to the discipline and context, as there is no single approach applicable across all fields. Research is not limited to academia—everyday life often involves informal research as individuals seek to solve problems or make informed decisions.It’s important to distinguish between two related but distinct activities: search and research. Both involve seeking information, but a search is about retrieving a known answer, while research is the process of exploring a problem without predefined answers. Research aims to expand knowledge and generate new insights, whereas search simply locates existing information.

Western Genealogy

The evolution of Modern Science, as we understand it today, and the establishment of the Scientific Research Method as the primary mode of knowledge construction, is deeply rooted in historical transformations across multiple spheres in Europe.

A critical historical catalyst for the emergence of modern science and scientific research methods was the decline of the medieval political order and the rise of modern nation-states in Europe. The new political entities not only redefined governance but also fostered environments where scientific inquiry could thrive, liberated from the previously dominant influence of religious institutions. Establishment of new universities and allocation of funding for scientific research by ‘new monarchs’ should be noted. These shifting power dynamics created space for scientific research more systematically. The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge was founded in 1662, while the French Academy of Sciences (Académie des Sciences) was established in 1666 under royal patronage to promote scientific research.

Alongside this political evolution, the feudal economic order declined, paving the way for modern capitalism. This transformation progressed through distinct stages, from early commercial capitalism to industrial capitalism. The rise of commercial capitalism created a new economic foundation that supported the funding and patronage of scientific research. With the advent of industrial capitalism, the expansion of factories, technological advancements, and the emphasis on mass production further accelerated innovation in scientific methods and applications, particularly in physics, engineering, and chemistry.

For centuries, the Catholic Church was the dominant ideological force in Europe, but its hegemony gradually declined. The Renaissance played a crucial role in challenging the Church’s authority over knowledge. This intellectual revival, along with the religious Reformation, fostered an environment conducive to alternative modes of thought. Scholars increasingly emphasised direct observation, experimentation, and logical reasoning—principles that became the foundation of modern science.

Research from Natural Science to Social Science

During this period, a new generation of scientists emerged, paving the way for groundbreaking discoveries that reshaped humanity’s understanding of the natural world. Among them, Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543), Johannes Kepler (1571–1630), Galileo Galilei (1564–1642), and Isaac Newton (1642–1726) made remarkable contributions, expanding the boundaries of human knowledge to an unprecedented level.

Like early scientists who sought to apply systematic methods to the natural world, several scholars aimed to bring similar principles of scientific inquiry to the study of human society and behavior. Among them, Francis Bacon (1561–1626) championed the empirical method, emphasising observation and inductive reasoning as the basis for knowledge. René Descartes (1596–1650) introduced a rationalist approach, advocating systematic doubt and logical deduction to establish fundamental truths. David Hume (1711–1776) further advanced the study of human nature by emphasizing empirical skepticism, arguing that knowledge should be derived from experience and sensory perception rather than pure reason alone.

Fundamentals of Modern Scientific Approach

The foundation of modern scientific research lies in the intricate relationship between perception, cognition, and structured reasoning.

Sensation, derived from our senses, serves as the primary gateway to understanding the world. It is through sensory experience that we acquire raw data, forming the fundamental basis of knowledge.

Cognition, in its essence, is a structured reflection of these sensory inputs. It does not exist in isolation but emerges as an organised interpretation of stimuli processed by the mind. The transition from mere sensory perception to structured thought is facilitated by the formation of concepts—complex cognitive structures that synthesize and categorize sensory experiences.

Concepts, once established, serve as the building blocks of higher-order thinking. They enable the formulation of judgments—assessments that compare, contrast, or evaluate information. These judgments, in turn, contribute to the development of conclusions, allowing for deeper reasoning and critical analysis.

A coherent set of judgments forms more sophisticated modes of thought, leading to structured arguments, hypotheses, and theoretical models. This continuous process of refining thought through judgment and reasoning is the driving force behind scientific inquiry, where knowledge is not only acquired but also systematically validated and expanded.

Modern scientific research, therefore, is a structured exploration of reality, rooted in sensory perception, refined through conceptualisation, and advanced through logical reasoning. This cyclical process ensures that scientific knowledge remains dynamic, evolving with each new discovery and theoretical advancement.

( Gamini Keerawella taught Historical Method, and Historiography at the University of Peradeniya, where he served as Head of the Department and Senior Professor of History. He is currently a Professor Emeritus at the same university)

by Gamini Keerawella

Midweek Review

Guardians of the Sanctuary

The glowing, tranquil oceans of green,

That deliver the legendary cup that cheers,

Running to the distant, silent mountains,

Are surely a sanctuary for the restive spirit,

But there’s pained labour in every leaf,

That until late was not bestowed the ballot,

But which kept the Isle’s economy intact,

And those of conscience are bound to hope,

That the small people in the success story,

Wouldn’t be ignored by those big folk,

Helming the struggling land’s marketing frenzy.

By Lynn Ockersz

-

Foreign News4 days ago

Foreign News4 days agoSearch continues in Dominican Republic for missing student Sudiksha Konanki

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoRichard de Zoysa at 67

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoThe Royal-Thomian and its Timeless Charm

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoDPMC unveils brand-new Bajaj three-wheeler

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days ago‘Thomia’: Richard Simon’s Masterpiece

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoSri Lanka to compete against USA, Jamaica in relay finals

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoSL Navy helping save kidneys

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoWomen’s struggles and men’s unions