Features

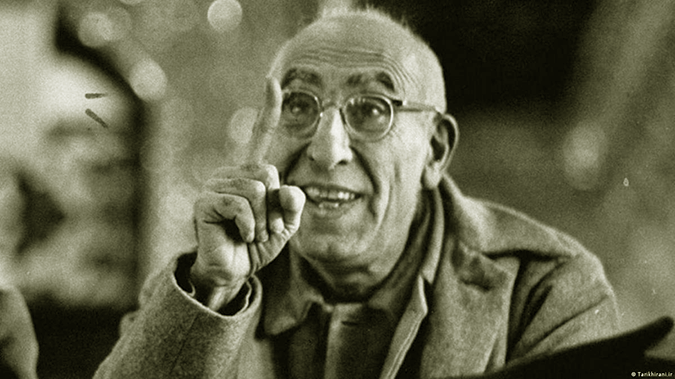

1953 ouster of PM Mosaddegh of Iran

By C.A.Chandraprema

The joint clandestine operation launched by the USA and Britain to oust Prime Minister Mohamed Mosaddegh of Iran in 1953 was a turning point in world history. (The CIA was established in 1947. Years later, misgivings among the American public resulted in the institution of Congressional inquiries into the secret operations of this organization. As a result of these inquiries, documents pertaining to the CIA’s clandestine operations were made public albeit in a heavily redacted form. This article is based entirely on the internal documents of the CIA which have thus been released into the public domain by the American government.)

When Iran entered the 1950s, the country had democratic institutions and political organisations that had evolved on the basis of the 1906 Constitution of Iran. Executive power was exercised in the name of the Shah of Iran by a cabinet of ministers headed by a Prime Minister. Legislative power was exercised by a Parliament (Majlis) of 136 elected MPs. The Parliament was vested with the power to nominate the Prime Minister while the Shah could either approve or disapprove of that choice. On 29 April 1951, Mosaddegh was appointed Prime Minister in accordance with that procedure. Within 72 hours of his assumption of office, the Iranian Parliament passed a resolution nationalising the British owned Iranian oil industry. That turned Britain against the new Prime Minister.

The cold war between Soviet Russia and the West was then at its height and the USA had been observing with great trepidation, the relationship that had been building up between Iran and Soviet Russia over a long period of time. From its very inception Soviet Russia had taken a very friendly attitude towards Iran. Iranian debts to Russia had been written off. Russian interests in several major Iranian infrastructure projects had been voluntarily relinquished. Since 1921, there was an understanding on security issues between the two countries. After the Second World War, three members of the Iranian Communist Party were accommodated in the Iranian cabinet as well. This was the backdrop in which the joint Anglo-American joint operation was launched to oust Premier Mosaddegh from power and to replace him with a Pro-Western Prime Minister.

Regime change money

On 4 April 1953 The CIA Director allocated a sum of one million US Dollars for the project to oust Premier Mosaddegh. These funds were to be used at the discretion of the US Ambassador and CIA station chief in Iran. In 1953, this was a colossal sum of money.

The main elements of the conspiracy were firstly to prevail upon the Shah to agree to aid the Western powers by dismissing Mosaddegh and appointing the joint US/British nominee General Fazlollah Zahedi as PM and secondly, to ensure that this change actually took palace. If by some chance the Shah had not agreed to dismiss the incumbent PM and replace him with a pro-Western nominee, plan B would be to seize power directly through a military coup. After having brought pressure on the Shah through various means to agree to the change of Prime Ministers – a risky affair because the people of Iran had got used to the existing political system over time – the conspirators had to ensure that this change actually took place. For this they needed support within Parliament, within the religious establishment, within the military and also among the public.

The conspirators were assisted in this ground level operation by the three Rashidyan brothers – a leading business family in Iran and two leading clerics who had fallen out with Mosaddegh. They had extensive contacts among all strata of Iranian society mentioned above and also in the Teheran Bazar and among street gangs as well.

By 20 May 1953, the CIA station chief had received authorisation to spend up to one million Riyals a week to buy support among Iranian parliamentarians. One owner of a media organisation was given a huge bribe of 45,000 to carry out anti-Mosaddegh propaganda. The conspirators set up a separate office to coordinate contacts with members of the Iranian armed forces and a sum of USD 75,000 was allocated for this purpose. By mutual agreement between the British and the Americans, buying support within the Iranian armed forces was assigned to the CIA. The operation to purchase support within the Iranian parliament was entrusted to the Rashidyan Brothers who were close to the British. Parliamentarians who would not yield were issued death threats with a view to neutralising them, by an extremist terrorist organization which was under the influence of one of the two clerics who had joined the conspiracy.

The plan to overthrow Mosaddegh was set in motion on the 15th of August 1953. Within the first 72 hours it appeared as if Premier Mosaddegh had been able to defeat the conspirators and retain control over Iran. The Shah fled to Baghdad in Iraq. Key figures in the conspiracy like General Zahedi and the Rashidyan brothers took refuge in safe houses maintained by the American Embassy. By the morning of the 19th August it appeared as if the conspiracy had been completely defeated. However due to a demonstration organised by the Rashidyan Brothers and the two clerics in the conspiracy on the 19th August, the situation underwent a complete change within a few hours.

Snatching victory from the jaws of defeat

The organisers of this demonstration had a keen understanding of the psyche of the Iranian people. They began attracting crowds onto the street by starting a procession of performers made up of Iran’s most popular wrestlers, body builders, acrobats and the like who were the equivalent of the cricket stars in India and Sri Lanka. A large crowd assembled within minutes to watch the procession. The security personnel on the streets had not done anything to disperse the crowd because this was seen as public entertainment and not as a political demonstration. Once they had drawn a large crowd onto the streets, on a cue, Iran’s most popular wrestling champion and the other entertainers had begun chanting pro-Shah and anti-Mosaddegh slogans.

In order to ensure maximum public participation at this demonstration the CIA had hand delivered on the morning of the 19th August, USD 10,000 to one of the two clerics involved in the conspiracy. It was later revealed that the participants sent to the demonstration by this cleric had been paid the equivalent of USD 27 in Iranian currency. The other cleric in the conspiracy had spent so much money to bring crowds to this demonstration that the payments he had doled out to participants had been known for years afterwards as ‘Behbahani Dollars’. According to a former CIA operative involved in this conspiracy, the extent to which US currency had been thrown around during the operation to oust Mosaddegh was such that the exchange rate in the Teheran black market had declined from about 100 Riyal to the Dollar to less than 50 during this period.

After the crowd assembled in this manner had been turned into a political mob by paid agents, they had attacked a pro-Mosaddegh newspaper office and other buildings belonging to pro-Mosaddegh elements and then marched on to surround Premier Mosaddegh’s house. At this point units of the army that had joined the conspiracy exchanged fire with Mosaddegh’s security detail. The latter tried to disperse the civilian crowd by firing over their heads but failed. After a nine-hour standoff interspersed with skirmishes, Mosaddegh’s security personnel were forced to surrender to the conspirators. By midnight on the 19th August Mosaddegh had been arrested and his tenure as Prime Minister had come to an end. General Zahedi became the new Prime Minister of Iran. After the ouster of Premier Mosaddegh, the operations of the Iranian oil industry was divided up as follows – 40% to the USA, 40% for the British, 14% for the Netherlands and 6% for the French.

As a result of this conspiracy, Iran came under a pro-Western dictatorship from 1953 to 1979. The great Iranian Islamic revolution which swept through Iran in 1979 in opposition to this dictatorship changed not only Iran but the entire Islamic world. Crown Prince Mohamed Bin Salman has explained to the world on many occasions how Saudi Arabia itself was forced to change due to the Islamic revolution in Iran. To this date there is intense mistrust, dislike and even hatred towards the USA among the Iranian people which all stems from the cynical and unprincipled coup carried out 70 years ago by the USA and Britain to oust a constitutionally appointed democratic Iranian leader. To this date many Iranians see the USA as the ‘Great Satan’. All of us are still living within the aftershocks of this conspiracy of 1953.

The successful coup in Iran later served as a model to oust democratic governments in other countries as well in the decades that followed.

Features

Rebuilding the country requires consultation

A positive feature of the government that is emerging is its responsiveness to public opinion. The manner in which it has been responding to the furore over the Grade 6 English Reader, in which a weblink to a gay dating site was inserted, has been constructive. Government leaders have taken pains to explain the mishap and reassure everyone concerned that it was not meant to be there and would be removed. They have been meeting religious prelates, educationists and community leaders. In a context where public trust in institutions has been badly eroded over many years, such responsiveness matters. It signals that the government sees itself as accountable to society, including to parents, teachers, and those concerned about the values transmitted through the school system.

This incident also appears to have strengthened unity within the government. The attempt by some opposition politicians and gender misogynists to pin responsibility for this lapse on Prime Minister Dr Harini Amarasuriya, who is also the Minister of Education, has prompted other senior members of the government to come to her defence. This is contrary to speculation that the powerful JVP component of the government is unhappy with the prime minister. More importantly, it demonstrates an understanding within the government that individual ministers should not be scapegoated for systemic shortcomings. Effective governance depends on collective responsibility and solidarity within the leadership, especially during moments of public controversy.

The continuing important role of the prime minister in the government is evident in her meetings with international dignitaries and also in addressing the general public. Last week she chaired the inaugural meeting of the Presidential Task Force to Rebuild Sri Lanka in the aftermath of Cyclone Ditwah. The composition of the task force once again reflects the responsiveness of the government to public opinion. Unlike previous mechanisms set up by governments, which were either all male or without ethnic minority representation, this one includes both, and also includes civil society representation. Decision-making bodies in which there is diversity are more likely to command public legitimacy.

Task Force

The Presidential Task Force to Rebuild Sri Lanka overlooks eight committees to manage different aspects of the recovery, each headed by a sector minister. These committees will focus on Needs Assessment, Restoration of Public Infrastructure, Housing, Local Economies and Livelihoods, Social Infrastructure, Finance and Funding, Data and Information Systems, and Public Communication. This structure appears comprehensive and well designed. However, experience from post-disaster reconstruction in countries such as Indonesia and Sri Lanka after the 2004 tsunami suggests that institutional design alone does not guarantee success. What matters equally is how far these committees engage with those on the ground and remain open to feedback that may complicate, slow down, or even challenge initial plans.

An option that the task force might wish to consider is to develop a linkage with civil society groups with expertise in the areas that the task force is expected to work. The CSO Collective for Emergency Relief has set up several committees that could be linked to the committees supervised by the task force. Such linkages would not weaken the government’s authority but strengthen it by grounding policy in lived realities. Recent findings emphasise the idea of “co-production”, where state and society jointly shape solutions in which sustainable outcomes often emerge when communities are treated not as passive beneficiaries but as partners in problem-solving.

Cyclone Ditwah destroyed more than physical infrastructure. It also destroyed communities. Some were swallowed by landslides and floods, while many others will need to be moved from their homes as they live in areas vulnerable to future disasters. The trauma of displacement is not merely material but social and psychological. Moving communities to new locations requires careful planning. It is not simply a matter of providing people with houses. They need to be relocated to locations and in a manner that permits communities to live together and to have livelihoods. This will require consultation with those who are displaced. Post-disaster evaluations have acknowledged that relocation schemes imposed without community consent often fail, leading to abandonment of new settlements or the emergence of new forms of marginalisation. Even today, abandoned tsunami housing is to be seen in various places that were affected by the 2004 tsunami.

Malaiyaha Tamils

The large-scale reconstruction that needs to take place in parts of the country most severely affected by Cyclone Ditwah also brings an opportunity to deal with the special problems of the Malaiyaha Tamil population. These are people of recent Indian origin who were unjustly treated at the time of Independence and denied rights of citizenship such as land ownership and the vote. This has been a festering problem and a blot on the conscience of the country. The need to resettle people living in those parts of the hill country which are vulnerable to landslides is an opportunity to do justice by the Malaiyaha Tamil community. Technocratic solutions such as high-rise apartments or English-style townhouses that have or are being contemplated may be cost-effective, but may also be culturally inappropriate and socially disruptive. The task is not simply to build houses but to rebuild communities.

The resettlement of people who have lost their homes and communities requires consultation with them. In the same manner, the education reform programme, of which the textbook controversy is only a small part, too needs to be discussed with concerned stakeholders including school teachers and university faculty. Opening up for discussion does not mean giving up one’s own position or values. Rather, it means recognising that better solutions emerge when different perspectives are heard and negotiated. Consultation takes time and can be frustrating, particularly in contexts of crisis where pressure for quick results is intense. However, solutions developed with stakeholder participation are more resilient and less costly in the long run.

Rebuilding after Cyclone Ditwah, addressing historical injustices faced by the Malaiyaha Tamil community, advancing education reform, changing the electoral system to hold provincial elections without further delay and other challenges facing the government, including national reconciliation, all require dialogue across differences and patience with disagreement. Opening up for discussion is not to give up on one’s own position or values, but to listen, to learn, and to arrive at solutions that have wider acceptance. Consultation needs to be treated as an investment in sustainability and legitimacy and not as an obstacle to rapid decisionmaking. Addressing the problems together, especially engagement with affected parties and those who work with them, offers the best chance of rebuilding not only physical infrastructure but also trust between the government and people in the year ahead.

by Jehan Perera

Features

PSTA: Terrorism without terror continues

When the government appointed a committee, led by Rienzie Arsekularatne, Senior President’s Counsel, to draft a new law to replace the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA), as promised by the ruling NPP, the writer, in an article published in this journal in July 2025, expressed optimism that, given Arsekularatne’s experience in criminal justice, he would be able to address issues from the perspectives of the State, criminal justice, human rights, suspects, accused, activists, and victims. The draft Protection of the State from Terrorism Act (PSTA), produced by the Committee, has been sharply criticised by individuals and organisations who expected a better outcome that aligns with modern criminal justice and human rights principles.

When the government appointed a committee, led by Rienzie Arsekularatne, Senior President’s Counsel, to draft a new law to replace the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA), as promised by the ruling NPP, the writer, in an article published in this journal in July 2025, expressed optimism that, given Arsekularatne’s experience in criminal justice, he would be able to address issues from the perspectives of the State, criminal justice, human rights, suspects, accused, activists, and victims. The draft Protection of the State from Terrorism Act (PSTA), produced by the Committee, has been sharply criticised by individuals and organisations who expected a better outcome that aligns with modern criminal justice and human rights principles.

This article is limited to a discussion of the definition of terrorism. As the writer explained previously, the dangers of an overly broad definition go beyond conviction and increased punishment. Special laws on terrorism allow deviations from standard laws in areas such as preventive detention, arrest, administrative detention, restrictions on judicial decisions regarding bail, lengthy pre-trial detention, the use of confessions, superadded punishments, such as confiscation of property and cancellation of professional licences, banning organisations, and restrictions on publications, among others. The misuse of such laws is not uncommon. Drastic legislation, such as the PTA and emergency regulations, although intended to be used to curb intense violence and deal with emergencies, has been exploited to suppress political opposition.

International Standards

The writer’s basic premise is that, for an act to come within the definition of terrorism, it must either involve “terror” or a “state of intense or overwhelming fear” or be committed to achieve an objective of an individual or organisation that uses “terror” or a “state of intense or overwhelming fear” to realise its aims. The UN General Assembly has accepted that the threshold for a possible general offence of terrorism is the provocation of “a state of terror” (Resolution 60/43). The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe has taken a similar view, using the phrase “to create a climate of terror.”

In his 2023 report on the implementation of the UN Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy, the Secretary-General warned that vague and overly broad definitions of terrorism in domestic law, often lacking adequate safeguards, violate the principle of legality under international human rights law. He noted that such laws lead to heavy-handed, ineffective, and counterproductive counter-terrorism practices and are frequently misused to target civil society actors and human rights defenders by labelling them as terrorists to obstruct their work.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) has stressed in its Handbook on Criminal Justice Responses to Terrorism that definitions of terrorist acts must use precise and unambiguous language, narrowly define punishable conduct and clearly distinguish it from non-punishable behaviour or offences subject to other penalties. The handbook was developed over several months by a team of international experts, including the writer, and was finalised at a workshop in Vienna.

Anti-Terrorism Bill, 2023

A five-member Bench of the Supreme Court that examined the Anti-Terrorism Bill, 2023, agreed with the petitioners that the definition of terrorism in the Bill was too broad and infringed Article 12(1) of the Constitution, and recommended that an exemption (“carve out”) similar to that used in New Zealand under which “the fact that a person engages in any protest, advocacy, or dissent, or engages in any strike, lockout, or other industrial action, is not, by itself, a sufficient basis for inferring that the person” committed the wrongful acts that would otherwise constitute terrorism.

While recognising the Court’s finding that the definition was too broad, the writer argued, in his previous article, that the political, administrative, and law enforcement cultures of the country concerned are crucial factors to consider. Countries such as New Zealand are well ahead of developing nations, where the risk of misuse is higher, and, therefore, definitions should be narrower, with broader and more precise exemptions. How such a “carve out” would play out in practice is uncertain.

In the Supreme Court, it was submitted that for an act to constitute an offence, under a special law on terrorism, there must be terror unleashed in the commission of the act, or it must be carried out in pursuance of the object of an organisation that uses terror to achieve its objectives. In general, only acts that aim at creating “terror” or a “state of intense or overwhelming fear” should come under the definition of terrorism. There can be terrorism-related acts without violence, for example, when a member of an extremist organisation remotely sabotages an electronic, automated or computerised system in pursuance of the organisation’s goal. But when the same act is committed by, say, a whizz-kid without such a connection, that would be illegal and should be punished, but not under a special law on terrorism. In its determination of the Bill, the Court did not address this submission.

PSTA Proposal

Proposed section 3(1) of the PSTA reads:

Any person who, intentionally or knowingly, commits any act which causes a consequence specified in subsection (2), for the purpose of-

(a) provoking a state of terror;

(b) intimidating the public or any section of the public;

(c) compelling the Government of Sri Lanka, or any other Government, or an international organisation, to do or to abstain from doing any act; or

(d) propagating war, or violating territorial integrity or infringing the sovereignty of Sri Lanka or any other sovereign country, commits the offence of terrorism.

The consequences listed in sub-section (2) include: death; hurt; hostage-taking; abduction or kidnapping; serious damage to any place of public use, any public property, any public or private transportation system or any infrastructure facility or environment; robbery, extortion or theft of public or private property; serious risk to the health and safety of the public or a section of the public; serious obstruction or damage to, or interference with, any electronic or automated or computerised system or network or cyber environment of domains assigned to, or websites registered with such domains assigned to Sri Lanka; destruction of, or serious damage to, religious or cultural property; serious obstruction or damage to, or interference with any electronic, analogue, digital or other wire-linked or wireless transmission system, including signal transmission and any other frequency-based transmission system; without lawful authority, importing, exporting, manufacturing, collecting, obtaining, supplying, trafficking, possessing or using firearms, offensive weapons, ammunition, explosives, articles or things used in the manufacture of explosives or combustible or corrosive substances and biological, chemical, electric, electronic or nuclear weapons, other nuclear explosive devices, nuclear material, radioactive substances, or radiation-emitting devices.

Under section 3(5), “any person who commits an act which constitutes an offence under the nine international treaties on terrorism, ratified by Sri Lanka, also commits the offence of terrorism.” No one would contest that.

The New Zealand “carve-out” is found in sub-section (4): “The fact that a person engages in any protest, advocacy or dissent or engages in any strike, lockout or other industrial action, is not by itself a sufficient basis for inferring that such person (a) commits or attempts, abets, conspires, or prepares to commit the act with the intention or knowledge specified in subsection (1); or (b) is intending to cause or knowingly causes an outcome specified in subsection (2).”

While the Arsekularatne Committee has proposed, including the New Zealand “carve out”, it has ignored a crucial qualification in section 5(2) of that country’s Terrorism Suppression Act, that for an act to be considered a terrorist act, it must be carried out for one or more purposes that are or include advancing “an ideological, political, or religious cause”, with the intention of either intimidating a population or coercing or forcing a government or an international organisation to do or abstain from doing any act.

When the Committee was appointed, the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka opined that any new offence with respect to “terrorism” should contain a specific and narrow definition of terrorism, such as the following: “Any person who by the use of force or violence unlawfully targets the civilian population or a segment of the civilian population with the intent to spread fear among such population or segment thereof in furtherance of a political, ideological, or religious cause commits the offence of terrorism”.

The writer submits that, rather than bringing in the requirement of “a political, ideological, or religious cause”, it would be prudent to qualify proposed section 3(1) by the requirement that only acts that aim at creating “terror” or a “state of intense or overwhelming fear” or are carried out to achieve a goal of an individual or organisation that employs “terror” or a “state of intense or overwhelming fear” to attain its objectives should come under the definition of terrorism. Such a threshold is recognised internationally; no “carve out” is then needed, and the concerns of the Human Rights Commission would also be addressed.

by Dr. Jayampathy Wickramaratne

President’s Counsel

Features

ROCK meets REGGAE 2026

We generally have in our midst the famous JAYASRI twins, Rohitha and Rohan, who are based in Austria but make it a point to entertain their fans in Sri Lanka on a regular basis.

We generally have in our midst the famous JAYASRI twins, Rohitha and Rohan, who are based in Austria but make it a point to entertain their fans in Sri Lanka on a regular basis.

Well, rock and reggae fans get ready for a major happening on 28th February (Oops, a special day where I’m concerned!) as the much-awaited ROCK meets REGGAE event booms into action at the Nelum Pokuna outdoor theatre.

It was seven years ago, in 2019, that the last ROCK meets REGGAE concert was held in Colombo, and then the Covid scene cropped up.

Chitral Somapala with BLACK MAJESTY

This year’s event will feature our rock star Chitral Somapala with the Australian Rock+Metal band BLACK MAJESTY, and the reggae twins Rohitha and Rohan Jayalath with the original JAYASRI – the full band, with seven members from Vienna, Austria.

According to Rohitha, the JAYASRI outfit is enthusiastically looking forward to entertaining music lovers here with their brand of music.

Their playlist for 28th February will consist of the songs they do at festivals in Europe, as well as originals, and also English and Sinhala hits, and selected covers.

Says Rohitha: “We have put up a great team, here in Sri Lanka, to give this event an international setting and maintain high standards, and this will be a great experience for our Sri Lankan music lovers … not only for Rock and Reggae fans. Yes, there will be some opening acts, and many surprises, as well.”

Rohitha, Chitral and Rohan: Big scene at ROCK meets REGGAE

Rohitha and Rohan also conveyed their love and festive blessings to everyone in Sri Lanka, stating “This Christmas was different as our country faced a catastrophic situation and, indeed, it’s a great time to help and share the real love of Jesus Christ by helping the poor, the needy and the homeless people. Let’s RISE UP as a great nation in 2026.”

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoSajith: Ashoka Chakra replaces Dharmachakra in Buddhism textbook

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoDialog and UnionPay International Join Forces to Elevate Sri Lanka’s Digital Payment Landscape

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoThe Paradox of Trump Power: Contested Authoritarian at Home, Uncontested Bully Abroad

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoSubject:Whatever happened to (my) three million dollars?

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoLevel I landslide early warnings issued to the Districts of Badulla, Kandy, Matale and Nuwara-Eliya extended

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoNational Communication Programme for Child Health Promotion (SBCC) has been launched. – PM

-

News2 days ago

News2 days ago65 withdrawn cases re-filed by Govt, PM tells Parliament

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoThe minstrel monk and Rafiki, the old mandrill in The Lion King – II