Features

Stop ragging!

Ragging is a social menace that plagues the higher educational institutes of Sri Lanka. The severity of the issue is so gripping that every year several deaths have been reported due to this. Young and vulnerable students who enter educational institutions, due to the lack of awareness, feel that ragging is the only pathway to form supporting friendships – especially those of senior students. But must a student’s mental well-being be compromised in the name of a so-called ‘bond-building culture’?

“Stop The Ragging” Session organised by the Rotaract Clubs of Centennial United, CFPS Law School, NIBM, Rathnapura, Peace City Hatton, Killinochi Town, Nallur Heritage and SLIIT in conjunction with the Break The Chain campaign was aimed at bringing light to this. The significant lack of knowledge amongst the new undergraduates about ragging and legal sanctions that could be pressed against offenders were the main points of focus.

With the pandemic situation all university students are stuck at home for over a year now, providing a perfect timely opportunity to work towards awareness-building on this pressing issue. Since no students physically engage with one another, there is no exposure to university sub-cultures.

These sessions were conducted via zoom and were trilingual – the first session on Tamil was conducted on 1st of August and the second and third were Sinhala and English held on the 14th and 15th of August respectively. An experienced panel of speakers, part of the Break The Chain Campaign, addressed several concerns and educated the audience on their legal rights.

Touching more than 350 students across the country, the discussions highlighted several methods by which first-year students could save themselves and effectively report such incidents in their respective institutions.

Features

Pestalotiopsis leaf disease will accelerate declining rate of natural rubber production

By Emeritus Professor Asoka Nugawela

Former Director, Rubber Research Institute of Sri Lanka and Chair Professor of Plantation Management,

Wayamba University of Sri Lanka

The natural rubber production in the country declined from 89 thousand metric tons in 2015 to 70 thousand metric tons in 2022 according to available statistics. This level of natural rubber production is insufficient to meet the demand for this raw material in the rubber product manufacturing sector of the country. Therefore, annually around 50 thousand metric tons of natural rubber are imported spending around 85 million US$.

Further, non-availability of the raw material in sufficient quantities is a hindrance to further growth of the rubber product manufacturing sector in the country. This is the scenario of the natural rubber industry in the country, which earned more than 1 b US$ per annum a couple of years ago, is facing today.

Why does production decline?

The national productivity of rubber cultivations is currently in the range of 650-700 kilos per hectare per year. Countries like India and Thailand records productivity levels of around 1,400 kgs per hectare per year. The relevant research institutes advocates that the potential productivity is around 2,500 to 3,000 kilos hectare year. So, in Sri Lanka a huge yield gap is evident.

Lower rate of technology adoption is a major reason for the yield gap. Death of plants due to pest and diseases, unproductive trees due to incidence of tapping panel dryness, extreme weather conditions negatively impacting the harvesting process and high cost of agro-chemicals prohibiting their use also contribute to yield gap.

In addition to the above factors causing the yield gap, it is now increasingly becoming evident that the Pestalotiopsis leaf disease, first recorded in Sri Lanka in 2019 is further widening the yield gap accelerating the declining rate of national rubber production in the country.

Impact of Pestalotiopsis on yield

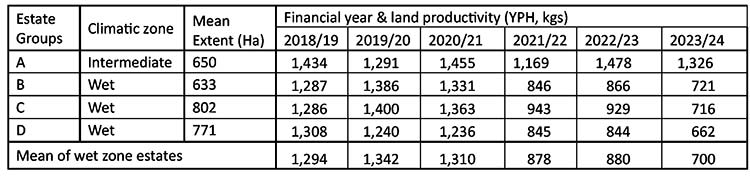

Yield data collected from a Regional Plantation Company having around 3,000 hectares of mature rubber cultivated in both intermediate and wet zones of the country was used to analyse impact of Pestalotiopsis leaf disease on rubber yield/productivity.

In the estates located in wet zone of the country, the Pestalotiopsis disease had been prevalent since 2019. Further, since the first reporting of the disease in 2019, its severity has increased. Each year apart from the normal natural leaf fall which take place in January/February, two other abnormal leaf falls occurred subsequent to both SW and NE monsoonal rains.

Therefore, three rounds of complete leaf fall have occurred in a year in rubber cultivations located in the wetter areas of the country since 2019. This scenario is despite the adoption all recommended good agricultural practices and also adopting recommended Pestalotiopsis management programs. However, the estates in the intermediate zone have not been affected by this disease. But even in the intermediate zone, in the year 2023 a mild incidence of Pestalotiopsis was evident in an area, which receives a relatively high level of rainfall.

Yield data gathered reveals that in estates located in the Pestalotiopsis disease prone wet zone a declining trend in land productivity/yield is apparent from financial year 2021/22 (Table 1). It should be mentioned that the yield decline in 2021/22 financial year is a combination of both Pestalotiopsis disease and a management decision not to undertake yield stimulation in fields tapped under low intensity tapping systems. This has caused a yield decline in the non Pestalotiopsis disease prone intermediate zone as well in 2021/22 (Table 1).

The mean land productivity/yield in the Pestalotiopsis prone wet zone reveals that the declining trend in yield increases year by year and in financial year 2023/24 the decline is more than 45% relative to the pre Pestalotiopsis period, i.e., 1,294 to 700 kgs/ha/year. The rubber growers expect the yield decline to be even higher in the coming years if no effective system is available to control this disease. It is very clearly evident that in the intermediate zone where Pestalotiopsis disease severity is marginal there is no such decline in land productivity/yield during this period (Table 1).

Sustainability

With the drop in yield likely to increase from the present 45% whilst the costs are continuously escalating, the rubber cultivations in the wetter region of the country will no longer be economically viable. It should also be emphasised that the young rubber clearings are also severely affected by this disease. The growth rates of young rubber plants have reduced which will lead to longer immature/uneconomical periods resulting in high capital costs.

Under such economic situations rubber growers will find it hard to invest on replanting, soil and moisture conservation, nutrient management and also to offer work to the workers threatening the sustainability of the industry under climatic conditions conducive to severe incidence of Pestalotiopsis. The income levels of the rubber harvesters too have dropped due to lower productivity affecting their livelihood and quality of life.

Way forward

Attempts are being made globally to find an effective chemical control method to combat this disease but without succes. Other options being looked at are breeding and selection for resistance and nutrient management. Finding solutions other than chemical control is going to be a mid/long term strategy. Further, there is no guarantee that a solution would be found.

In the light of this situation, the authorities should consider other possible interventions to resolve this issue, which is seriously threatening the viability of rubber cultivations in the wetter areas of traditional rubber growing regions. One such intervention to be considered seriously by relevant authorities/policy makers is to promote and support the cultivation of rubber in the intermediate zone of the country in order to escape from the disease.

Features

Kevum,Krida , and Kade : Avurudu in Colombo

By Uditha Devapriya and Pasindu Nimsara

No Avurudu would be complete without an Avurudu Ulela. It has become part of our national social calendar, an event that must be organised, a tradition that must be kept. Practically every institution, from nurseries to universities to companies to Rotaract Societies, has a shot at holding one. The result is that somehow or the other, an Avurudu Ulela unfolds somewhere every other day until the end of April.

In Colombo, and most major cities, Avurudu Ulela, or Festivals, serve a decorative function. They are designed, structured, and “ordered” to represent the ideal of Avurudu. This is hardly a radical suggestion, but it underlies an important point: in a typical Avurudu Festival, or at least the best among them, spectators are made to imagine what Avurudu means, or rather is supposed to mean. Our contention here is that such festivals focus on the basic elements of Avurudu, a trinity of sorts: kevum (food), krida (games), and kade (shops, stalls, and kiosks). This is rather simplistic, but it reinforces the point.

Christmas is often touted as a time for family. Avurudu, by contrast, is a communal affair, even if consumerism, urbanisation, and the mass media have made it more individualistic and family oriented. In line with this, Avurudu Festivals strive to be as communal as they can, promoting shared experiences. And yet, the idea of communalism – in the positive sense, not negative – has undergone a transformation over the years, particularly in the cities. Today you “take time off” for an Avurudu Ulela: you take the bus or your vehicle, travel all the way from somewhere or the other to the location. The event itself becomes a highly atomised affair, resembling a function rather than a festival.

Such transformations are only to be expected in a society that is becoming more specialised and specialist every day. These transformations did not begin yesterday. They are part of a broader cultural change. Over the last 25 or so years, there has been a radical shift in the social composition in cities like Colombo, including suburbs. In light of these developments, the very character of Avurudu Festivals has undergone a transition.

This is true not just of the events we take part at these festivals, or the food we eat, but even what we wear. Ever since batiks took off and became a “cultural industry” here, lungis and baniyans have become highly exoticised things. We wear them and then take them off: they enable us to become “locals”, or more specifically, “villagers.” They are as decorative and ornamental as the masks and sculptures at Laksala and Barefoot. Like anthropologists, we descend on these practices every year, turning the very idea of a communal gathering into a function, an event, or for the lack of a still better word, a spectacle.

At first glance, this seems a radical way of looking at Avurudu – specifically, the way it is celebrated and viewed in Colombo. But there is nothing really radical here. In Colombo – and in cities and even in villages which are fast being swamped by the “civilising” forces of “modernity” – the most traditional events get “routinised.” We no longer “have” fun, we “experience” it.

The most rudimentary element, including music, gets “scheduled” and forms part of an agenda. Avurudu songs become as predictable as baila at a Big Match: they are there to bring out the joie de vivre of the event, but organisers ensure they are in line with a set pattern. In a culture where work and leisure have become atomised, these events and festivals offer a form of leisure that sits in well with their sensibilities.

Without idealising or fetishising what life in a typical Sinhala village would have been like hundreds of years ago, it’s evident that work and leisure were never compartmentalised as they are today. Rituals were not something to be kept at a distance: they formed a part of everyday, ordinary life. Avurudu marked the end of a harvest season and the beginning of another. The festivals were incidental to this transition: they did not lie away from them. Most of the Avurudu songs that are performed today celebrate this. But in celebrating it, we have externalised it, or as the purists would have it, commercialised it.

Avurudu is not the only festival that has been ruptured this way: Christmas, even Vesak and Poson, have been radically transformed, sometimes beyond recognition. Like Christmas, Avurudu is a “pagan” ritual: it incorporates a mishmash of pre-Buddhist rites that have since been absorbed into Sri Lanka’s unique Buddhist ethos. And like every such festival that has been “modernised” and brought up to date, it has also become a highly exotic affair. Yet unlike Christmas, Vesak, and Poson – which have been transformed to such an extent that it is difficult to imagine what they looked or felt like before the “forces of modernity” crept in – Avurudu gives us a chance to imagine the concept of the village, or gama.

Every year, hundreds of Avurudu Festivals crop up in Colombo and other cities. In almost all of them, there is an almost subconscious attempt to replicate the gama, mainly through that trinity of rites we mentioned earlier: kema, krida, and kade. By replicating it, the organisers try to reimagine that village, though not always accurately. More so than Christmas, and certainly more so than Vesak and Poson, in an Avurudu Festival one discerns a fixation with the Sinhala village which has permeated and continues to permeate our thinking.

Our conception of that village may be at odds with the historical reality. And more often than not, it is. Yet Avurudu Festivals in Colombo, though following a certain pattern, offer a window to that ideal, a chance to relive and embody it.

In that sense, the most interesting Avurudu Festivals in Colombo would be those organised by villagers. Such festivals would reveal not just how those in the city reconceive the Sinhala gama, but also, crucially, how Sinhala villagers reconceive the city and refract Colombo’s reimagining of the gama. While this looks like an oddity, something that simply does not happen, there is one such festival that unfolds every year at the heart of Colombo which is organised by “villagers” – and intriguingly, is open to a large crowd.

This is the Avurudu Ulela organised by the Hostellers of Royal College Colombo. Home to over 300 students, the Hostel has today transformed into what can best be called a nexus between the city and the village. Most of the localities its students hail from lie more than 50 kilometres from Colombo. This has enabled a transmission of cultural values, but more importantly, a two-way exchange of cultural values: from the rural to the urban, and as crucially, from the urban to the rural. Such transmissions and exchanges are evident in the many events and festivals that these students organise.

The Hostel Avurudu is no exception. Unlike most school Avurudu Festivals, the parents don’t get involved in the organising: the students do. This enables them to structure the event in line with their conceptions of village and city. It unfolds in a set pattern, beginning with a customary milk boiling ceremony, moving on to a satirical skit, transitioning to breakfast, games, lunch, and still more games, well into the night. At the centre of it all is a telling titled gama gedara, which represents the household of an influential villager: a reflection of the social class to which most of the students – many of whom are sons of teachers, bus owners, public health inspectors, and the like – themselves belong.

What is interesting is how culturally dualistic the Festival becomes, which puts it a cut above most other festivals organised in Colombo. The rural seeps into the urban, but the urban seeps into the rural as well. To give just one example, the satirical skit which unfolds in the morning at the gama gedara is dominated by an arachchi, one of the most recognisable Sinhala rural archetypes.

In popular culture, including teledramas, the arachchi invariably has a wayward son and a pretty daughter, not to mention a group of servile acolytes. This is reflected in the skit itself. Yet, interestingly enough, and no doubt because of the rural origins of the organisers, there is an authenticity in the way the actors playing these parts deliver their lines and act out various situations.

The Hostel Avurudu is, in that sense, an exception. The function of an Avurudu Festival, at the end of the day, is to bring people together. In Colombo, it has acquired a logic and a character of its own, helping us reimagine the Sinhala gama in the most creative, exotic, yet “orientalist” ways possible. The Hostel Avurudu strays from this tendency, and presents a view of the gama that is at once urbanised, refined, and also much more authentic. We have been to many Festivals, in the village and city. The Hostel Avurudu represents something of a synthesis of them. At one level, it is an interesting study for scholars.

Uditha Devapriya is a writer, researcher, and analyst based in Sri Lanka who contributes to a number of publications on topics such as history, art and culture, politics, and foreign policy. He can be reached at .

Pasindu Nimsara was the Deputy Head Prefect of the Royal College Hostel in 2022. He is now preparing for his higher studies. An ardent reader of anthropology, he hopes to study and pursue the subject. He can be reached at .

Features

BETWEEN ABSTRACTION & EMPATHY IN SARATH CHANDRAJEEWA’S VISUAL PARAPHRASES – PART II

by Dr. Santhushya Fernando,

Dr. Laleen Jayamanne and Professor Sumathy Sivamohan

We, three academics, coming from three different intellectual disciplines (Medicine, English Literature, Theatre and Film Studies) worked alongside each other here so as to understand this mysterious process of a ‘will to abstraction’ or non-objective art, evident in Sarath’s work. None of us are art historians but are learning on the run its diverse histories and theories relevant to our topic. Of the three of us, Santhushya and Sumathy have seen the exhibition, while Laleen has seen it telescopically, only on her computer and in the paper Catalogue to the exhibition, from Sydney.

So, she believes that the other two friends and colleagues are her microscopic eyes. All of us know Sarath’s work (artistic and scholarly) to some degree, and have worked with him but Santhushya has known him intimately since childhood as well. Sumathy contributed a poem and a photograph of and a poem by her sister Rajani to the Jaffna Doors and Windows book, a collective multi-ethnic project conceived and produced by Sarath. Laleen however, though she has written on Sarath’s work, has never met him nor spoken with him or seen his work with her own eyes.

But before the angel of death calls, she hopes to visit the Sri Lankan High Commission in Canberra to see his large figurative clay mural of folk traditions, celebrating our multi-ethnic Island home. It is a contribution to Australian culture too which has nourished several distinguished Lankan artists (Dharmasena and Milinda Pathiraja), and scholars (Michael Roberts, Neville Weerarathne, Anoma Pieris), and provided some with a hospitable home in an expansive multi-cultural ethos.

German Art History and Theory

Wilhelm Worringer’s Abstraction and Empathy: A Contribution to the Psychology of Style (1908), is a very popular art history book from which we have borrowed our title. A slim doctoral dissertation, it’s still read and commented on by scholars in its many editions and translations. We find the way Worringer conceptualised the history of art and its genesis useful and cite it here to structure our argument as it has a similar understanding of pre-historical art as Leroi-Gourhan.

As well, coming from a training in the rigorous German philosophically grounded, philological tradition of aesthetics, he is not shy to speculate on the basis of empirical work, albeit done in the metropolitan ethnographic museums of Imperial Europe enriched by the looted patrimony of faraway colonised countries and peoples. The following summary explains briefly the derivation of the two key ideas structuring this piece.

“What proved to be so timely in Abstraction and Empathy was Worringer’s further claim that this will to abstraction was to be understood to be one of the two fundamental aesthetic impulses known to human culture – the other, of course, being the urge to empathy which manifests itself in the naturalistic depiction of the observable world.

Basing his studies on diverse cultures, styles, and periods, Worringer found “the need for empathy and the need for abstraction to be the two poles of human artistic experience …. They are antitheses which, in principle, are mutually exclusive. In actual fact, however, the history of art represents an unceasing disputation between the two tendencies.” Hilton Kramer, Introduction to Abstraction and Empathy.

We frame our piece with these two interdisciplinary ideas of abstraction and empathy, formulated by Leroi-Ghouran and Worringer. Sarath’s paintings shuttle between these two impulses, the purely abstract pole of mark making and colour and also a mixed figurative mode or semi-abstraction. Thinker in Front of The Empty Doorway and The Ascetic are among the latter.

His pure colour fields appear not to be ‘abstract’ so much as the place where our brain encountering colour might experience a ‘pure affect’; the emergence of some new quality, which we critics have to struggle to name. There is no possible ‘empathetic’ response here because colour in such a field derails habitual mechanisms of recognition of a familiar object. There is nothing there to empathise with through recognition of the familiar. The statement by Cezanne which frames this piece makes sense in this specific context; ‘Colour is the place where our brain and the universe meet’. Colour makes one vibrate with intensity if one yields to it.

Marx’s work on the economy is abstract; and his abtract is the most concrete too; about matter, wages, exchange, capital. Laleen, you trace art through the materiality of human evolution, of the body, the brain and cognition as social evolution. I am so much in the here and now. I can only see the hand that works, with its material, and the artist in a relationship with the world around her, in her surroundings and in her place as an artisan.

So, the artist is an artisan after all. This shuttling back and forth between the artist and artisan, without rest and without the dichotomy and distinction ever resolved, is what we embrace I think, not as art, not as artisanal craft, but as a reflective, intimate space, in which we can reside and reflect. Not to freeze material, the labour of the craftsperson and the artist to reverberate through the meanings they can generate at that moment. The classic distinction between the abstract and the realist may have to be dissolved here as well.

All art has to be abstract at one level, for it is not immediately palpable, real or intimate. It is a form of writing after all. So, the question of abstract and realist art as distinct forms troubles me. Working in film, like Laleen, I am also very profoundly aware how a verisimilitude, animates realist art, undone by what we see in abstraction. Laleen says that she is drawn to the stature of the Thinker that Sarath has.

We already have the figure of the Thinker in Rodin. Do we immediately know to make those connections, and therefore think of the Thinker? Or is it a MAN holding himself in a ‘thoughtful’ pose which kindles that idea? Sarath’s art is abstract – but they build on the ideas of palpable forms of the real – images of the war that have come to be both tactile material, like the wood, and have come to stand for the dislocation of war.

At the exhibition, there are several paintings of Doors and Windows, in splatters of dark and bright colours, flying in opposite directions but kept together and formed through the materiality of paint and canvas, – this is what makes the abstraction of that painting, so severe and demanding on one to be an insider, in the know, to be let in on a secret. I am neither a painter or an art critic. But I felt that Sarath had quick brush strokes.

They capture the flight of the doors and windows, through the broken roofs and the open roofs of the sky. But they are contained. They can never fly away. We are constrained by our thoughts, and our bodies, compelled to reflect on the here and now. Why am I here, now at this exhibition. Why am here in the middle of an exhibit?

Bronze Statues and Body-Counts

Sumathy, you mentioned that you came down to Colombo that evening, after teaching at Peradeniya, and arrived straight from the station lugging your bags, to attend the special viewing for invitees, a collective celebration. It was important for you to be there. You mention Sarath’s recent commemorative statue of Sir Ivor Jennings and pose a generative question. What did he see as he strode forward, in planning a visionary public University for independent Lanka on that magnificent location?

But, because Sarath made a statue of former president Premadasa, he has been permanently blacklisted by the gate keepers of important art institutions, both locally and internationally, thereby erasing him from the Lankan art historical record. I have attempted to talk about his work with a few Lankan critics and curators and have been repeatedly rebuffed, straining cherished friendships. If we were to do an approximate body-count of just the young intelligentsia killed by our rulers since April 1971, then several other statues now standing proudly, would also have to be toppled.

Is it only the ‘working-class man/thug’ from Maradana become president, who is guilty of mass murder? When Ivor Jennings gazed out with his bronze eyes, at that vista of Paradise which is the Peradeniya campus, he could not have imagined that just within two decades of its founding, bombs would go off in a hall of residence and young men and women’s wounded bodies would be floating down that majestic Mahawali river flowing though the campus.

Fallen Monument

Then I landed on one painting and gazed at it. It is once again of broken forms, but arranged in such a way, that pointed to a space, that I can formulate as home, as Jaffna. But this is Jaffna returned to me, in blacks, whites and punctured colours. I did not know whether I read any of it correctly. So, I kept quiet there. And carefully conveyed that idea to Laleen, who pounced on it as a seminal thought. The shape of Jaffna is distinctive, for those who gaze upon maps of Sri Lanka and have been made to gaze upon it for the last 30-odd years.

The muted colours of this picture are quite different from the fiery ones of doors and windows that threaten to fly into a nowhere, and forever tied to the present. This is the abstraction perhaps I can speak of. The abstraction of generative readings, that take us elsewhere, in the bond between artist and subject as I have noted above, but also in the bond between the body of the viewer stretched within the spaces of the painting, as she tried to take it all in, in one fell scoop, but cannot. For one has to reflect, think, and formulate.

(To be concluded)

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoSinhala and Tamil New Year auspicious times

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoSOEs seen as failing SL’s ordinary citizens

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoSay no to NEPF! Say no to abolishing free education!

-

News6 days ago

News6 days ago123rd Birth anniversary of Dr S A Wickramasinghe commemorated

-

Business16 hours ago

Business16 hours agoSLFEA appoints JAT as a Facilitation Partner for training painters to provide overseas employment opportunities

-

Midweek Review3 days ago

Midweek Review3 days agoBetween abstraction and empathy in Sarath Chandrajeewa’s visual paraphrases

-

Latest News3 days ago

Latest News3 days agoFormer Member of Parliament Palitha Thewarapperuma passes away

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoSri Lanka Tourism concludes another round of Roadshows in Australia