Life style

Career choice in the midst of a revolution

Confessions of a Global Gypsy

By Dr. Chandana (Chandi) Jayawardena DPhil Insurgency!

The 5th of April has been a bad day for Ceylon. On that day in 1942, the Japanese bombed Colombo. Exactly 29 years later, on the same day in 1971, an armed revolt was commenced by the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) against the Government of Ceylon. The JVP was successful in recruiting a force of around 10,000 full-time members. Most were students and unemployed youth from rural areas who felt that their economic interests had been neglected by the government. The JVP believed that the local police stations were the government’s key element of power. Therefore, they hoped to remove this presence of power and see the local populace rise up in their support to bring about a revolution.

I was 17-years old at that time, and was a grade 12 student at Ananda College in Colombo 10. For months, we felt the tension building, with police looking suspiciously at youth in their late teens, particularly those with facial hair like me. In the opinion of police, such youth were expressing their solidarity with the JVP and sympathy with the late Che Guevara (killed  by CIA in 1967), who was a key inspiration to the JVP. At dawn on April 5, 1971, the Wellawaya police station came under attack and five police constables were killed by the JVP. With that fatal attack a bloody war commenced. All schools were closed indefinitely, curfews were in force, and a state of emergency was declared. That day my life changed, forever…

by CIA in 1967), who was a key inspiration to the JVP. At dawn on April 5, 1971, the Wellawaya police station came under attack and five police constables were killed by the JVP. With that fatal attack a bloody war commenced. All schools were closed indefinitely, curfews were in force, and a state of emergency was declared. That day my life changed, forever…

Army?

Throughout my 13 years from Kindergarten to grade 12, I was a very bad student at Ananda College. I declined to read any assigned texts, and devoutly ignored homework assignments. Therefore, my teachers were surprised when I passed the grade 10 Ordinary Level government examinations on my first attempt. I was good at sports and showed some leadership qualities. I practiced Judo at the central YMCA, and represented the school in Rugby Football. I was average in track and field events, but was elected by my peers as one of the four Athletic House Captains.

More importantly, I was a cadet and held the rank of Corporal. During my annual cadeting trips to army camps in Diyatalawa, I decided that I would join the Army as an officer cadet for a two-year training program when I turned 18. My career ambition was to then get promoted as a Second Lieutenant at age 20, with a long-term goal of eventually becoming a General in my early-40s. That was my dream, but it was shattered when my parents had a serious meeting with me during the height of the JVP insurgency. They told me that: “a career in the Army is now far too dangerous and we do not want our only son to die at war!”. That was the end of that discussion.

Choices

I was forced to choose another career. As my parents had doubts that I would be successful at grade 12 Advance Level government examinations to enter a university, they gave me three choices and wanted me to pick one. My father provided some pros and cons for all three choices:

Visual Arts – Just like my parents, I was good in drawing, painting, and sculpture. Therefore, one option for me was to do a three-year Diploma at Heywood Art School and build a career in visual arts. My father said: “No doubt that you will enjoy it, but we are not sure if you could make a comfortable living from art in a poor country!”

Trainee in a Company – My father had some good contacts with large companies, and said that: “I can find a junior trainee job for you where you will have to start at the bottom.”

Hospitality and Tourism – My father then said that: “Once the war ends, Tourism has the potential of becoming a key non-traditional industry in Ceylon, and those who earn a recognized qualification and join the industry at an early stage of this industry will have good opportunities to do well. There is a Hotel School in Colombo, run by European faculty, which offers a three-year diploma in Hotel and Catering Operations”.

At that time, I had enjoyed meeting a few foreigners and tourists by the Kinross Swimming & Life Saving Club in Wellawatte, where I used to jog and sea bathe with a few of my buddies from Bambalapitiya Flats, without our parent’s knowledge. Therefore, the opportunity to meet European faculty was interesting to me. Living in a hostel for three years and getting good and “free” food were also encouraging selling points from my father. I said: “OK, I will become a hotelier!”, without fully realizing what that notion, really entailed.

Challenges

I soon realized that I had a major challenge in joining the Ceylon Hotel School (CHS). At that time, we rarely spoke English at Ananda College. Therefore, I became very nervous when my father told me that the education at CHS would be conducted in English with French and German as mandatory subjects. Another challenge was that at 17-years, I was underage to join CHS. Once again, I thought about other options. After two weeks of fighting with JVP, the government regained control of all but a few remote areas of the island and the war ended in June of 1971. At that point, I attempted to convince my parents that my proposed Army career would be less dangerous than what they had predicted. I was unsuccessful in convincing them.

I eventually applied to CHS. As I was not sure if I would do well at my first-ever interview, my father did a series of mock interviews in English, at home. I learned English words such as “cutlery”, “crockery”, and “wine” for the first time during my interview preparation. Despite this, I did terribly at the interview. There were hundreds of applicants for 28 vacancies, and I doubted that I would be chosen. During that time in Ceylon, many things happened based on “political pull” rather than the true merits of applicants. Most of the applicants to CHS were from influential families. Therefore, I was surprised when I received a letter confirming that I had been accepted to CHS. We did not talk about it, but I was convinced that my father “did the needful” to get me chosen!

I eventually applied to CHS. As I was not sure if I would do well at my first-ever interview, my father did a series of mock interviews in English, at home. I learned English words such as “cutlery”, “crockery”, and “wine” for the first time during my interview preparation. Despite this, I did terribly at the interview. There were hundreds of applicants for 28 vacancies, and I doubted that I would be chosen. During that time in Ceylon, many things happened based on “political pull” rather than the true merits of applicants. Most of the applicants to CHS were from influential families. Therefore, I was surprised when I received a letter confirming that I had been accepted to CHS. We did not talk about it, but I was convinced that my father “did the needful” to get me chosen!

Shock!

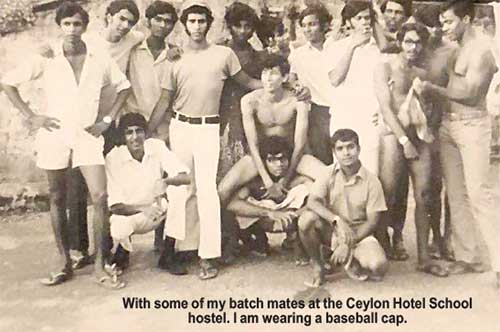

I was still not out of the woods. I had to practice a lot and improve my English before the first day at CHS. When my father finally accompanied me to the CHS hostel in Steuart Place, Colombo 3 (where SLTDA and SLITHM are located, now) on Sunday, October 10, 1971, I was in for a rude shock. Instead of a warm welcome by the second-year and third-year students, a horrible week-long ragging (initiation ritual or hazing) was awaiting the batch of 28 new students. Soon after the parents left, the ragging began.

The freshers were told that they could not address senior students by their names unless they added the words “Lord Veteran” to their names, as a mark of respect. Similarly, freshers were strictly prohibited from mentioning their own names without adding the words “Fresher F***er”. For an example, I had to introduce myself, repeatedly throughout the first week, as: “Fresher F***er Chandana Jayawardena”.

(The writer is President – Chandi J. Associates Inc. Consulting, Canada

Founder & Administrator – Global Hospitality Forum

chandij@sympatico.ca )

Some more challenges followed over my memorable and eventful three years at CHS. More, next week…

Life style

SOS Wonder Village at One Galle Face Mall

SOS Children’s Villages Sri Lanka, in partnership with One Galle Face Mall Colombo, presented the SOS Wonder Village event, an initiative aimed at raising funds and awareness for the well-being of children in need.

The SOS Wonder Village took place at the Level 4 Playscape at One Galle Face Mall Colombo, recently

The SOS Wonder Village event at One Galle Face promises a day of fun, learning, and philanthropy. By participating, attendees will not only enjoy exciting activities but also contribute to the betterment of children’s lives.

The SOS Wonder Village event features an array of engaging activities for attendees of all ages. Visitors can enjoy free painting sessions for children, youth, and adults, and a variety of indoor games. Exciting prizes await competition winners. Participants will also be able to sponsor a child under the care of SOS Childrens’ Village by pledging a monthly or yearly donation which would be utilized for the child’s educational and living expenses. Additionally, attendees will have the opportunity to learn about child safeguarding and enjoy children’s videos, cartoons, and songs.

Commenting on the project, Mr.Divakar Ratnadurai, National Director, SOS Children’s Villages Sri Lanka said, “At SOS Children’s Villages Sri Lanka, our mission is to provide a loving family environment for children without parental care or at risk of losing it. Through the SOS Wonder Village event, we hope to not only raise funds but also increase awareness about the importance of child safeguarding and the support needed for these vulnerable children.”

SOS Children’s Villages Sri Lanka has been actively engaged in providing a stable, family-like environment for children for 42 years, operating 06 Children’s Villages and caring for over 800 children. The organization is dedicated to extending assistance to more than 3700 children at risk of losing their parents through the Direct Family Empowerment Programme.

Sharing his thoughts on this partnership, Mr. Sid Solanki, Centre Director, One Galle Face stated, “We are delighted to partner with SOS Children’s Villages Sri Lanka for this fun-filled yet meaningful event. One Galle Face and the Shangri-La Group is committed to our belief of “Do Good” and we look to support – initiatives that positively impact our community, through advocacy and positive action. We believe the SOS Wonder Village is uniquely positioned to enhance the quality of life and provide much needed access to education and other opportunities to many children in need.”

SOS Village Sri Lanka invites everyone to participate in the SOS Wonder Village and contribute in making a meaningful impact, spreading joy to those who need it most, creating a brighter future for every child.

Life style

Nyne Hotels: Redefining Hospitality with an All-Encompassing Sensory Experience

by Zanita Careem

Nayantara Fonseka, a successful entrepreneur, designer and interior decorator, affectionately known as Taru, has unveiled Nyne Hotels, creating a benchmark in hospitality. Having a keen eye for design and detailing,

she has turned her hotels into spaces where guests indulged in an experience, luxury and comfort throughout their stay. Her collection of luxury boutique hotels, has sophisticated interiors, decorative themes and immaculate service. An art collector, design afficionado and a creative power house, no doubt she claimed that she in the pioneer of boutique hotels in Sri Lanka that are architecturally unique.

Nayantara has introduced a fresh perspective to the world of hospitality. This visionary entrepreneur have re-define luxury, weaving her unique stories and experiences into the fabric of her properties. Why the change of name? She replied, it is now time to move on Nyne hotels is my new passion, she told the Sunday Island at the launch of Nyne. . With plans to open three more properties in Bentota 2024. Nyne hotels will be a brand that focuses on providing a holistic sensory experience for guests.

Nayantara Fonseka (Taru), launches Nyne Hotels, marking a new chapter in hospitality excellence and creativity. This transition isn’t merely a name change; it signifies the brand’s commitment to providing unparalleled experiences that engage with all nine senses (vision, hearing, smell, taste, touch, balance, intuition, time, and presence).

The significance of the number nine is rooted in completeness and culmination: at Nyne Hotels, it represents the pinnacle of our dedication to crafting extraordinary moments for our guests, where senses are indulged and experiences are transformative. “Our journey with Nyne Hotels is a testament to our passion for excellence and innovation in hospitality,” said Nayantara Fonseka , the founder and chairperson of Nyne Hotels. “We believe in going beyond the ordinary to create experiences that leave a lasting impression on our guests.”

Nyne Hotels isn’t just about accommodation; it’s about curating sensory journeys that revitalise the soul. From visually captivating designs to the aroma of exotic scents, from the melody of nature’s symphony to the tantalising flavours of culinary delights, Nyne Hotels invites guests on a voyage of discovery. “Our goal is to engage not just the traditional senses, but all nine senses,”. “We want our guests to experience their holiday in a way they’ve never imagined, to be fully present and immersed in the moment.”

The Nyne Hotels website www.nynehotels.com serves as a portal to this sensory world, inviting guests to explore our unique offerings and tailor their experiences to their preferences. From tranquil retreats to vibrant cultural hubs, each Nyne Hotels property offers a distinct ambience that celebrates local heritage and artistry.

Lake Lodge in Colombo is a contemporary green oasis, offering guests a quiet neighbourhood escape from the bustling city streets. Meanwhile, Rock Villa in Bentota embodies understated luxury, with its tropical bungalow architecture and sprawling gardens. The Muse, also in Bentota, exudes timeless style, while Leela Walauwwa in Induruwa evokes the charm of a bygone era. Landesi, which means ‘of Dutch origin’ in Sinhala, is a manor house set in the 17th-century Galle Fort, which is now a UNESCO World Heritage site. Mayur Lodge – Yala is a hidden gem nestled amidst the ‘Chena’ farming community, and offers a contemporary villa in a jungle environment, on the outskirts of the famed safari destination, Yala National Park.

“Our properties are more than just hotels; they are reflections of their destination,”. “Each property tells a story, weaving together elements of local history, culture, and art to create an authentic experience for our guests. We are proud to say that we will be adding further properties to our portfolio by the end of 2024, including three in Bentota.”

At Nyne Hotels, art is more than decoration; it’s an integral part of the guest experience. From paintings and sculptures to installations and performances, art is woven into the fabric of each property, inviting guests to engage with their surroundings in new and unexpected ways. “Being passinate about creating, I understand the power of art to evoke emotion and inspire imagination,”. “That’s why we’re committed to showcasing local talent and supporting the arts in all its forms.”

In addition to its commitment to sensory indulgence and artistic expression, Nyne Hotels is dedicated to sustainability and social responsibility. From eco-friendly practices to community engagement initiatives, Nyne Hotels strives to make a positive impact on the world around it. “As stewards of the environment and champions of local communities, we believe in leaving a legacy that extends beyond our boundries,”. “By embracing sustainability and social responsibility, we can create a brighter future for generations to come.”

As Nyne Hotels continues to expand its portfolio, with new properties set to open in the coming year, the brand remains committed to its core values of excellence, creativity, and authenticity. From secluded retreats to vibrant urban escapes, Nyne Hotels welcomes guests on a journey of discovery, teaming with opportunities to engage their senses and nourish their souls. For more information and bookings, visit www.nynehotels.com.

Lake Lodge – Colombo: A Contemporary Retreat in the City

Secluded from the buzzing streets of Colombo, Lake Lodge is imbued with a heritage tracing back to 1967, the country’s first registered and officially recognised ‘Guest House’, the words used back then to describe this genre. . Lake Lodge is a welcome respite from the bustling city with ten attentively composed rooms. Expect top-tier service and privacy at all times. Dining at Table by Nyne promises a unique culinary journey, with a marriage of Sri Lankan and international cuisine that attracts a loyal local and cosmopolitan fanbase of diners.

Meanwhile, the discreet gallery of public and private spaces within the Lake Lodge property offers a feast for the eyes, showcasing over 50 works of art by renowned artists, including Priyantha Udagedara and Kingsley Gunatillake.

Rock Villa– Bentota: Tropical Bungalow by the Sea Surrounded by three acres of frangipani and meticulous rows of coconut trees, Rock Villa’s serene sanctuary encompasses a 180-year-old Walauwwa, the name given to ancestral heritage homes. The oft-imitated welcome popsicle, our blend of fresh mint and tangy passionfruit, sets the tone for an indulgent stay where every detail matters.

Filled with Sri Lankan collectables and a palette of white, beige and pops of turquoise, Rock Villa’s sprawling property is a laid-back tropical indulgence. Laze in an unspoiled beach beyond the single-track railway line, dip in one of the azure-blue pools, meander through the cooling mangroves, enter bliss in the spa or retreat into one of nine varied, well-appointed rooms.

Artfully-plated gastronomy and antique hand-carved wooden trellises for discretion elevate your stay from start to finish. An astounding display of over 90 pieces of work by celebrated local artists grace the walls of this silent art exposition.

The Muse – Bentota:Tranquil Seclusion with Artistic Flair

Tranquil and captivating, The Muse is where generous Sri Lankan hospitality enters absolute contentment. With nine divinely comfortable rooms and breezy open-plan living, it promises picture-postcard corners for an unforgettable family staycation or a quiet hideaway for two.

In this one-of-a-kind escape, step over the single gauge railway track and stroll across the powder-soft sea sand, feel quietness amongst mangroves, dip in the aquamarine pool or deep-dive into tantalising food.

Leela Walauwwa– Induruwa: A Heritage Haven of Serenity

Narrow winding roads snake through dense foliage to transport you to this rural manor house dating back two centuries. Its charming heritage promises to entice with colonial architecture, secret gardens and a gazebo made for meditation or reflection. Antique four poster beds in four supremely comfortable rooms and intricately-carved furniture give you more than a hint of the splendour of its past, immaculately restored to modern comfort.

Do take the opportunity of an art class led by the Villa Guardian, a well-known artist, to release the creativity in you. You’ll find it effortless, with the numerous works of art and sculpture surrounding you.

.Mayur Lodge – Yala: A Hidden Gem Within Nature

Off the beaten track, hidden away in the rural hinterlands on the outskirts of Yala National Park, Mayur Lodge is a four-acre retreat surrounded by nature. You will enjoy frequent sightings of the abundant birdlife and foraging peacocks and peahens after whom this lodge is aptly named: Mayur means peacock in Sanskrit.

. Landesi – Galle:A Stately Retreat Steeped in History

Landesi is Sinhala for ‘of Dutch origin’. Fitting, as this manor house graces the vicinity of a fort fortified by the Dutch in the 17th century, now a UNESCO World Heritage site. This stately house was designed and built by renowned architect Ashley de Vos, a conservationist of the Galle Fort who expertly retained the classic features of the period.

Inside, art by famous local artists including Laki Senanayake and several lithographs by Donald Friend enhance this house’s unique and special character. All around outside, are the feats of the mastery of culture and history to engage with.

Life style

When The Clock Strikes And The Wolf Howls”: Unveiled by Soul Sounds Players

In a fusion of creativity and passion, the Soul Sounds Players, under the guidance of renowned theater specialist Jerome L. De Silva, proudly present their latest theatrical endeavor, “When The Clock Strikes And The Wolf Howls.” What began as a humble course in musical theater has blossomed into an extraordinary creation that promises to captivate audiences with its depth, drama, and sheer originality.

The journey of the Soul Sounds Players commenced in October 2022 with a simple three-month course, but it soon evolved into a transformative two-year exploration of the possibilities inherent in the world of theater. Drawing from their collective imagination and ingenuity, the Players have crafted an exquisite production that defies convention and invites audiences into a world of family intrigue, mystery, and the complexities of war.

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCEAT Kelani launches 3 new radial tyre variants in ‘Orion Brawo’ range

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoSOEs seen as failing SL’s ordinary citizens

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoSay no to NEPF! Say no to abolishing free education!

-

Midweek Review4 days ago

Midweek Review4 days agoBetween abstraction and empathy in Sarath Chandrajeewa’s visual paraphrases

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoDialog-Airtel Lanka merger comes centre stage

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoSLFEA appoints JAT as a Facilitation Partner for training painters to provide overseas employment opportunities

-

Latest News4 days ago

Latest News4 days agoFormer Member of Parliament Palitha Thewarapperuma passes away

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoSri Lanka Tourism concludes another round of Roadshows in Australia