Opinion

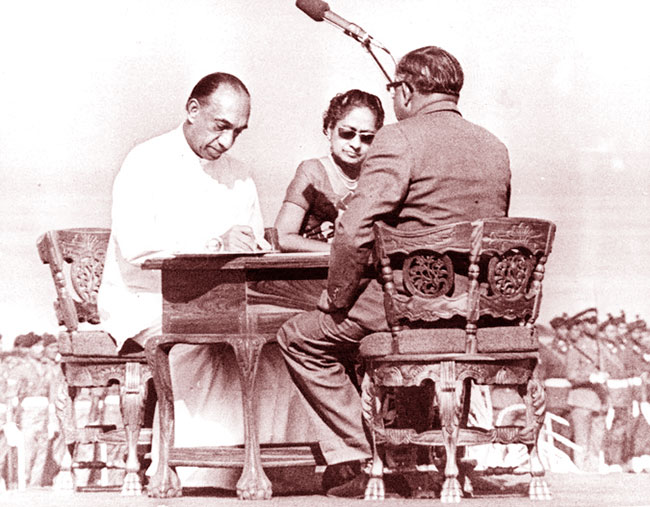

1972: Another in a history of missed opportunities

1972 Construction in Retrospect – II

By Dr. Jayampathy Wickramaratne,

President’s Counsel

In the two earlier parts of this article, the writer dealt with the Constituent Assembly process that led to the First Republican Constitution and how the Constitution led to constitutionalising majoritarianism in multi-cultural Sri Lanka. In a country with a history of missed opportunities, 1972 was another.

Fundamental rights

A noteworthy feature of the 1972 Constitution is the recognition of fundamental rights. Principles of State Policy contained in another chapter were to guide the making of laws and the governance of Sri Lanka. But these Principles did not confer legal rights and were not enforceable in a court of law.

The fundamental rights guaranteed by the 1972 Constitution, however, were mainly civil and political rights: equality and equal protection, freedom from arbitrary deprivation of life, liberty and security of person, freedom of thought, conscience and religion, freedom to enjoy and promote one’s culture, freedoms of assembly, association, speech and expression, movement and residence and freedom from discrimination in appointments in the public sector. But all these rights were subject to such restrictions as the law may prescribe in the interests of national unity and integrity, national security, national economy, public safety, public order, the protection of public health or morals or the protection of rights and freedoms of others or giving effect to the Principles of State Policy.

Thus, even the freedom from arbitrary deprivation of life and the freedom of thought, conscience and religion could be restricted. While Principles of State Policy did not confer legal rights, fundamental rights could be restricted to give effect to such principles. In several cases, the Constitutional Court held that impugned provisions of Bills that were prima facie inconsistent with fundamental rights were nevertheless for the purposes of giving effect to Principles of State Policy. It is hard to see the rationale for permitting fundamental rights, which bind all organs of government, to be restricted in the interests of Principles of State Policy which are only for guidance in law-making and governance and are not enforceable.

Much has been said about the new constitution not having a provision equivalent to section 29 (2) of the Soulbury Constitution. While the fundamental right to equality and equal protection was a safeguard against discrimination, it was subject to wide restrictions, unlike section 29 (2), which was absolute. Also, section 29 (2) was in the nature of a group right. Although it was not as effective as it was expected to be, as was demonstrated by the failure to invoke it to prevent the disenfranchisement of hundreds of thousands of Hill-Country Tamils, numerically smaller ethnic and religious groups nevertheless felt comfortable that it existed, at least on paper. They saw its omission from the 1972 Constitution as a move towards majoritarianism, especially in the context that Sri Lanka was declared a unitary state, Buddhism given the foremost place, and Sinhala declared to be the only official language.

With the ‘Republic pledged to realise the objectives of a socialist democracy’, the non-inclusion of second-generation human rights based on the principles of social justice and public obligation is puzzling. Important examples of such rights that could have been included are the right to just and favourable conditions of work, equal work for equal pay, right to rest and leisure as an employee, right to free elementary education, right to food, clothing, housing, medical care and necessary social services and right to special care and assistance for mothers and children.

Section 18 (3) of the 1972 Constitution provided that all existing laws shall operate notwithstanding any inconsistency with fundamental rights. This was in sharp contrast to the Constitution of India, which provides in Article 13 (1) that all laws in force before the commencement of the Constitution, in so far as they are inconsistent with fundamental rights, shall, to the extent of such inconsistency, be void. The 1972 Constitution did not provide for a special jurisdiction of a court for the enforcement of fundamental rights against the executive arm of the State. Theoretically, fundamental rights could have been enforced through writs in public law as well as through actions for damages, declaratory actions and injunctions in civil courts. There is only one known fundamental rights case under the 1972 Constitution, Gunaratne v People’s Bank, a declaratory action arising out of the famous bank strike of the 1970s.

Constitutionality of legislation

A significant feature of the 1972 Constitution was that, unlike under the Independence Constitution, a law could not be challenged for constitutionality. Post-enactment judicial review of legislation was thus taken away. Chapter X provided for pre-enactment judicial review. A Bill could be challenged in the Constitutional Court within a week of it being placed on the agenda of the National State Assembly (NSA).

A Bill which is, in the view of the Cabinet of Ministers, urgent in the national interest shall be referred to the Constitutional Court which shall communicate its advice to the Speaker as expeditiously as possible and in any case within twenty-four hours of the assembling of the Court.

An argument against post-enactment judicial review is that there should be certainty as regards the constitutionality of legislation. However, no serious problems have arisen in jurisdictions where post-enactment judicial review is permitted. To mitigate hardships that may be caused by legal provisions being struck down years later, the Indian Supreme Court has used the tool of ‘prospective over-ruling,’ limiting the retrospective effect of a declaration of invalidity in appropriate cases. Section 172 of the South African Constitution expressly permits such limitation.

Post-enactment judicial review is an essential tool to prevent infringement of constitutional provisions by legislative action. The effect of most legislative provisions is felt only when they are being enforced. Another argument in favour of post-enactment judicial review is that the people are able to get the benefit of the latest judicial interpretation of a constitutional provision. There have been many instances of obviously unconstitutional provisions going unchallenged. Provisions relating to urgent Bills have been abused by successive administrations. An urgent Bill is referred directly to the Supreme Court by the President even without a Gazette notification. Such a Bill is not tabled in Parliament before such reference and even Members of Parliament would not know the contents of such a Bill.

Judiciary

Under the Independence Constitution, the Chief Justice, the Judges of the Supreme Court and Commissioners of Assize were appointed by the Head of State, on the advice of the Prime Minister. The 1972 Constitution made no change in that regard.

In relation to other judicial officers, however, the provisions of the new constitution were very unsatisfactory.

Since 1946, the appointment, transfer, dismissal and disciplinary control of judicial officers had been vested in a Judicial Service Commission consisting of the Chief Justice, a Judge of the Supreme Court and another person who is or has been a Judge of the Supreme Court.

The 1972 Constitution provided for a five-member Judicial Services Advisory Board (JSAB) and a three-member Judicial Services Disciplinary Board (JSDB), both headed by the Chief Justice. A list of persons recommended for appointment as judicial officers and state officers exercising judicial functions would be forwarded by the JSAB to the Cabinet of Ministers, which was the appointing authority. The Cabinet reserved for itself the right to appoint a person not recommended by the JSAB, subject to the proviso that the full list of JSAB-recommended names and the reasons for non-acceptance of anyone so recommended were tabled in the NSA. Dismissal and disciplinary control were exercised by the JSDB, which was required to forward a report to the Cabinet through the Minister of Justice and a copy transmitted to the Speaker. A judicial officer could also be removed for misconduct by the President on an address by the NSA. J.A.L. Cooray considered the changes effected by the 1972 Constitution to be hardly compatible with the independence of the judicial function. (Constitutional and Administrative Law of Sri Lanka, 2nd edn, 69).

Public service

Under the Independence Constitution, the Permanent Secretary of each ministry was subject to the general direction and control of the Minister in exercising supervision over the departments coming under the ministry. The 1972 Constitution made no change to this position except to include institutions, such as corporations, within the ambit of the relevant provision.

Before 1972, the appointment, transfer, dismissal and disciplinary control of public officers were vested in a Public Service Commission appointed by the Governor-General. This position was changed, and the powers were taken over by the Cabinet of Ministers. Appointments were made after receiving recommendations from a State Services Advisory Board. The power of appointment could be delegated to the Minister concerned or by the Minister, in turn, to any state officer. The power of disciplinary control and dismissal was exercised after receiving a recommendation from the State Services Disciplinary Board.

The UF no doubt considered the bureaucracy to be obstructionist and wished the public service to be available to the government to accelerate socio-economic development. This is understandable. As Radhika Coomaraswamy has argued in Sri Lanka, The Crisis of the Anglo-American Constitutional Traditions in a Developing Society, the framers of the 1972 Constitution considered the checks and balances contained in the 1947 Constitution appearing to obstruct decision-making, perpetuating a status quo of privilege and domination. But rather than including appropriate constitutional provisions to ensure that political decisions were carried out by the bureaucracy, the entire public service was placed under the control of the political executive, eroding the independence that it enjoyed.

Legality and legitimacy of the Constitution

1972 was undoubtedly a legal revolution. According to L. J. M. Cooray, the question of the legality of the process followed does not arise. ‘One might just as well ask: Was the American War of Independence legal? The Constituent Assembly of Sri Lanka was part of a revolution, which aimed at overthrowing the existing constitution.’ As to the ‘legality’ of the new Constitution, Cooray stated: ‘It could be answered by posing the question: Does the stigma of illegality apply to the United States Constitution or to the Bill of Rights and the Acts of Settlement which followed the 1699 Revolution [of Britain]?’ A constitution becomes legal in the course of time if it is accepted by the people, the courts and the administration. This requirement was fulfilled in respect of the 1972 Constitution, Cooray opines. Constitutional Government in Sri Lanka, 1796-1977 (Lake House 1984) 246-247.

Legality apart, did the 1972 Constitution have the necessary legitimacy? With all political parties agreeing on the Constituent Assembly process, it was a unique opportunity to adopt a constitution that had the support of the people at large. But, instead, the United Front imposed upon the country a constitution of its choice.

Rather than impose its will on the Constituent Assembly, the UF should have accommodated the views of the various parties that answered its call to take the Constituent Assembly route. Such accommodation would have given greater legitimacy to the 1972 Constitution. That ‘legitimacy deficit’ of the 1972 Constitution no doubt helped J. R. Jayewardene, who succeeded the liberal-minded Dudley Senanayake as the leader of the UNP, to impose his own will in turn in the form of the 1978 Constitution with which the country is still straddled.

Concluding remarks

While the complete break from the British Crown, retention of the parliamentary form of government, the introduction of a fundamental rights chapter and declaration of principles of state policy were undoubtedly laudable, the 1972 Constitution also paved the way for majoritarianism and undermining of the concepts of the rule of law and the supremacy of the constitution.

1972 was also a historic opportunity to accommodate the diversity and pluralism of the people of Sri Lanka in state power and resolve the language question, an opportunity that tragically was missed. If the United Front had met the Federal Party halfway, the history of this country might have been significantly different.

Opinion

Thoughts for Unduvap Poya

Unduvap Poya, which falls today, has great historical significance for Sri Lanka, as several important events occurred on that day but before looking into these, as the occasion demands, our first thought should be about impermanence. One of the cornerstones of Buddha’s teachings is impermanence and there is no better time to ponder over it than now, as the unfolding events of the unprecedented natural disaster exemplify it. Who would have imagined, even a few days ago, the scenes of total devastation we are witnessing now; vast swathes of the country under floodwaters due to torrential rain, multitudes of earth slips burying alive entire families with their hard-built properties and closing multiple trunk roads bringing the country to a virtual standstill. The best of human kindness is also amply demonstrated as many risk their own lives to help those in distress.

In the struggle of life, we are attached and accumulate many things, wanted and unwanted, including wealth overlooking the fact that all this could disappear in a flash, as happened to an unfortunate few during this calamitous time. Even the survivors, though they are happy that they survived, are left with anxiety, apprehension, and sorrow, all of which is due to attachment. We are attached to things because we fail to realise the importance of impermanence. If we do, we would be less attached and less affected. Realisation of the impermanent nature of everything is the first step towards ultimate detachment.

It was on a day like this that Arahant Bhikkhuni Sanghamitta arrived in Lanka Deepa bringing with her a sapling of the Sri Maha Bodhi tree under which Prince Siddhartha attained Enlightenment. She was sent by her father Emperor Ashoka, at the request of Arahant Mahinda who had arrived earlier and established Buddhism formally under the royal patronage of King Devanampiyatissa. With the very successful establishment of Bhikkhu Sasana, as there was a strong clamour for the establishment of Bhikkhuni Sasana as well, Arahant Mahinda requested his father to send his sister which was agreed to by Emperor Ashoka, though reluctantly as he would be losing two of his children. In fact, both served Lanka Deepa till their death, never returning to the country of their birth. Though Arahant Sanghamitta’s main mission was otherwise, her bringing a sapling of the Bo tree has left an indelible imprint in the annals of our history.

According to chronicles, King Devanampiyatissa planted the Bo sapling in Mahamevnawa Park in Anuradhapura in 288 BCE, which continues to thrive, making it the oldest living human planted tree in the world with a known planting date. It is a treasure that needs to be respected and protected at all costs. However, not so long ago it was nearly destroyed by the idiocy of worshippers who poured milk on the roots. Devotion clouding reality, they overlooked the fact that a tree needs water, not milk!

A monk developed a new practice of Bodhi Puja, which even today attracts droves of devotees and has become a ritual. This would have been the last thing the Buddha wanted! He expressed gratitude by gazing at the tree, which gave him shelter during the most crucial of times, for a week but did not want his followers to go around worshipping similar trees growing all over. Instead of following the path the Buddha laid for us, we seem keen on inventing new rituals to indulge in!

Arahant Sanghamitta achieved her prime objective by establishing the Bhikkhuni Sasana which thrived for nearly 1200 years till it fell into decline with the fall of the Anuradhapura kingdom. Unfortunately, during the Polonnaruwa period that followed the influence of Hinduism over Buddhism increased and some of the Buddhist values like equality of sexes and anti-casteism were lost. Subsequently, even the Bhikkhu Sasana went into decline. Higher ordination for Bhikkhus was re-established in 1753 CE with the visit of Upali Maha Thera from Siam which formed the basis of Siam Maha Nikaya. Upali Maha Thero is also credited with reorganising Kandy Esala Perahera to be the annual Procession of the Temple of Tooth, which was previously centred around the worship of deities, by getting a royal decree: “Henceforth Gods and men are to follow the Buddha”

In 1764 CE, Siyam Nikaya imposed a ‘Govigama and Radala’ exclusivity, disregarding a fundamental tenet of the Buddha, apparently in response to an order from the King! Fortunately, Buddhism was saved from the idiocy of Siyam Nikaya by the formation of Amarapura Nikaya in 1800 CE and Ramanna Nikaya in 1864 CE, higher ordination for both obtained from Burma. None of these Niakya’s showed any interest in the re-establishment of Bhikkhuni Sasana which was left to a band of interested and determined ladies.

My thoughts and admiration, on the day Bhikkhuni Sasana was originally established, go to these pioneers whose determination knew no bounds. They overcame enormous difficulties and obtained higher ordination from South Korea initially. Fortunately, Ven. Inamaluwe Sri Sumangala Thero, Maha Nayaka of Rangiri Dambulla Chapter of Siyam Maha Nikaya started offering higher ordination to Bhikkhunis in 1998 but state recognition became a sore point. When Venerable Welimada Dhammadinna Bhikkhuni was denied official recognition as a Bhikkhuni on her national identity card she filed action, with the support of Ven. Inamaluwe Sri Sumangala Thero. In a landmark majority judgement delivered on 16 June, the Supreme Court ruled that the fundamental rights of Ven. Dhammadinna were breached and also Bhikkhuni Sasana was re-established in Sri Lanka. As this judgement did not receive wide publicity, I wrote a piece titled “Buddhism, Bhikkhus and Bhikkhunis” (The Island, 10 July 2025) and my wish for this Unduvap Poya is what I stated therein:

“The landmark legal battle won by Bhikkhunis is a victory for common sense more than anything else. I hope it will help Bhikkhuni Sasana flourish in Sri Lanka. The number of devotees inviting Bhikkhunis to religious functions is increasing. May Bhikkhunis receive the recognition they richly deserve.” May there be a rapid return to normalcy from the current tragic situation.”

by Dr Upul Wijayawardhana

Opinion

Royal Over Eighties

The gathering was actually of ‘Over Seventies’ but those of my generation present were mostly of the late eighties.

Even of them I shall mention only those whom I know at least by name. But, first, to those few of my years and older with whom speech was possible.

First among them, in more sense than one, was Nihal Seneviratne, at ninety-one probably the oldest present. There is no truth to the story that his state of crisp well-being is attributable to the consumption of gul-bunis in his school days. It is traceable rather to a life well lived. His practice of regular walks around the house and along the lane on which he lives may have contributed to his erect posture. As also to the total absence of a walking stick, a helper, or any other form of assistance as he walked into the Janaki hotel where this gathering took place.

Referencing the published accounts of his several decades-long service in Parliament as head of its administration, it would be moot to recall that his close friend and fellow lawyer, J E D Gooneratne, teased him in the following terms: “You will be a bloody clerk all your life”. He did join service as Second Assistant to the Clerk to the House and moved up, but the Clerk became the Secretary General. Regardless of such matters of nomenclature, it could be said that Nihal Seneviratne ran the show.

Others present included Dr. Ranjith de Silva, Surgeon, who was our cricket Captain and, to the best of my knowledge, has the distinction of never engaging in private practice.

The range of Dr. K L (Lochana) Gunaratne’s interests and his accomplishments within each are indeed remarkable. I would think that somebody who’d received his initial training at the AA School of Architecture in London would continue to have architecture as the foundation of his likes /dislikes. Such would also provide a road map to other pursuits whether immediately related to that field or not. That is evident in the leadership roles he has played in the National Academy of Sciences and the Institute of Town Planners among others. As I recall he has also addressed issues related to the Panadura Vadaya.

My memories of D L Seneviratne at school were associated with tennis. As happens, D L had launched his gift for writing over three decades ago with a history of tennis in Sri Lanka (1991). That is a game with which my acquaintance is limited to sending a couple of serves past his ear (not ‘tossing the ball across’ as he asked me to) while Jothilingam, long much missed, waited for his team mates to come for practices. It is a game at which my father spent much time both at the Railway sports club and at our home-town club. (By some kind of chance, I recovered just a week ago the ‘Fred de Saram Challenge Cup’ which, on his winning the Singles for the third time, Koo de Saram came over to the Kandana Club to hand over to him for keeps. They played an exhibition match which father won). D L would know whether or not, as I have heard, in an exhibition match in Colombo, Koo defeated Frank Sedgman, who was on his triumphant return home to Oz after he had won the Wimbledon tournament in London.

I had no idea that D L has written any books till my son brought home the one on the early history of Royal under Marsh and Boake, (both long-bearded young men in their twenties).

It includes a rich assortment of photographs of great value to those who are interested in the history of the Anglican segment of Christian missionary activity here in the context of its contribution to secondary school education. Among them is one of the school as it appeared on moving to Thurstan road from Mutwal. It has been extracted from the History of Royal, 1931, done by students (among whom a relative, Palitha Weeraman, had played a significant role).

As D L shows, (in contra-distinction to the Catholic schools) the CMS had engaged in a largely secular practice. Royal remained so through our time – when one could walk into the examination room and answer questions framed to test one’s knowledge of Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism and Islam; a knowledge derived mostly from the lectures delivered by an Old Boy at general assembly on Friday plus readings from the Dhammapada, the Bhagavad Gita, the St. John’s version of the Bible or the Koran recited by a student at senior assembly on Tuesday / Thursday.

D L’s history of Royal College had followed in 2006.

His writing is so rich in detail, so precise in formulation, that I would consider this brief note a simple prompt towards a publisher bringing out new editions at different levels of cost.

It was also a pleasure to meet Senaka Amarasinghe, as yet flaunting his Emperor profile, and among the principal organisers of this event.

The encounter with I S de Silva, distinguished attorney, who was on Galle road close to Janaki lane, where I lived then was indeed welcome. As was that with Upali Mendis, who carried out cataract surgery on my mother oh so long ago when he was head of the Eye Hospital. His older brother, L P, was probably the most gifted student in chemistry in our time.

Most serendipitous perhaps was meeting a son of one of our most popular teachers from the 1950s, – Connor Rajaratnam. His cons were a caution.

by Gamini Seneviratne

Opinion

“Regulatory Impact Assessment – Not a bureaucratic formality but essentially an advocacy tool for smarter governance”: A response

Having meticulously read and re-read the above article published in the opinion page of The Island on the 27 Nov, I hasten to make a critical review on the far-reaching proposal made by the co-authors, namely Professor Theekshana Suraweera, Chairman of the Sri Lanka Standards Institution and Dr. Prabath.C.Abeysiriwardana, Director of Ministry of Science and Technology

The aforesaid article provides a timely and compelling critique of Sri Lanka’s long-standing gaps in evidence-based policymaking and argues persuasively for the institutional adoption of Regulatory Impact Assessment (RIA). In a context where policy missteps have led to severe economic and social consequences, the article functions as an essential wake-up call—highlighting RIA not as a bureaucratic formality but as a foundational tool for smarter governance.

One of the article’s strongest contributions is its clear explanation of how regulatory processes currently function in Sri Lanka: legislation is drafted with narrow legal scrutiny focused mainly on constitutional compliance, with little or no structured assessment of economic, social, cultural, or environmental impacts. The author strengthens this argument with well-chosen examples—the sudden ban on chemical fertilizer imports and the consequences of the 1956 Official Language Act—demonstrating how untested regulation can have far-reaching negative outcomes. These cases effectively illustrate the dangers of ad hoc policymaking and underscore the need for a formal review mechanism.

The article also succeeds in demystifying RIA by outlining its core steps—problem definition, option analysis, impact assessment, stakeholder consultation, and post-implementation review. This breakdown makes it clear that RIA is not merely a Western ideal but a practical, structured, and replicable process that could greatly improve policymaking in Sri Lanka. The references to international best practices (such as the role of OIRA in the United States) lend credibility and global context, showing that RIA is not experimental but an established standard in advanced governance systems.

However, the article could have further strengthened its critique by addressing the political economy of reform: the structural incentives, institutional resistance, and political culture that have historically obstructed such tools in Sri Lanka. While the challenges of data availability, quantification, and political pressure are briefly mentioned, a deeper analysis of why evidence-based policymaking has not taken root—and how to overcome these systemic barriers—would have offered greater practical value.

Another potential enhancement would be the inclusion of local micro-level examples where smaller-scale regulations backfired due to insufficient appraisal. This would help illustrate that the problem is not limited to headline-making policy failures but affects governance at every level.

Despite these minor limitations, the article is highly effective as an advocacy piece. It makes a strong case that RIA could transform Sri Lanka’s regulatory landscape by institutionalizing foresight, transparency, and accountability. Its emphasis on aligning RIA with ongoing national initiatives—particularly the strengthening of the National Quality Infrastructure—demonstrates both pragmatism and strategic vision.

At a time, when Chairmen of statutory bodies appointed by the NPP government play a passive voice, the candid opinion expressed by the CEO of SLSI on the necessity of a Regulatory Impact Assessment is an important and insightful contribution. It highlights a critical missing link in Sri Lanka’s policy environment and provides a clear call to action. If widely circulated and taken seriously by policymakers, academics, and civil society, it could indeed become the eye-opener needed to push Sri Lanka toward more rational, responsible, and future-ready governance.

J. A. A. S. Ranasinghe,

Productivity Specialty and Management Consultant

(rathula49@gmail.com)

-

News5 days ago

Lunuwila tragedy not caused by those videoing Bell 212: SLAF

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoLevel III landslide early warning continue to be in force in the districts of Kandy, Kegalle, Kurunegala and Matale

-

Latest News6 days ago

Latest News6 days agoLevel III landslide early warnings issued to the districts of Badulla, Kandy, Kegalle, Kurunegala, Matale and Nuwara-Eliya

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoDitwah: An unusual cyclone

-

Latest News7 days ago

Latest News7 days agoUpdated Payment Instructions for Disaster Relief Contributions

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoCPC delegation meets JVP for talks on disaster response

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoLOLC Finance Factoring powers business growth

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoA 6th Year Accolade: The Eternal Opulence of My Fair Lady