Features

Using maths to combat COVID-19

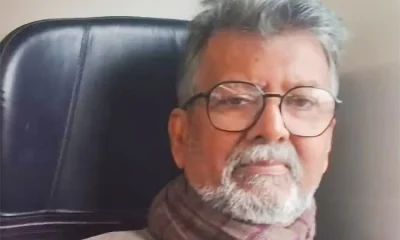

‘The pandemic has now reached a level in which no human can make an optimal decision without the aid of a computer. Therefore, we need to start working on quantitative models to identify optimal decisions, instead of pointing fingers for not making proper decisions, when decision making is literally beyond the capacity of a human.’ – Senior Lecturer, Department of Mathematics, University of Colombo,

Dr. Anuradha Mahasinghe

by Sajitha Prematunge

What has math got to do with a pandemic? At the outset, it might seem the two are completely unrelated. One has only to observe that the number of infected in certain districts is higher than that of others and making informed decisions based on those numbers could mean the difference between stifling a cluster and a full-blown third wave. Senior Lecturer, Department of Mathematics, University of Colombo, Dr. Anuradha Mahasinghe knows only too well how important the numbers are in combating COVID-19. This is why, in June, he and his colleagues proposed an optimization model, aimed at minimizing the damage to the economy, while confining the COVID-19 incidence to a level endurable by the available healthcare capacity in the country, while their compartment model projected COVID-19 transmission. Their study investigated the effectiveness of the control process with the aid of epidemiological models.

Epidemiological models

Mahasinghe explained that an epidemiological model is a model that simulates and describes an epidemic. “Modelling is essential if you want to describe a phenomenon. From the spin of an electron to the rotation of the heavenly bodies, these phenomena are understood with the aid of models. It is the models that help us describe the changes in economies and fall of financial markets,” said Mahasinghe. And pandemics are no exception. He explained that an epidemiological model, based on a reasonable theory and supported by evidence, is a collection of entities and their operations, that when put together simulate and describe an epidemic, which provides important insights into the transmission of the disease.

But how does maths factor comes in when dealing with a pandemic such as COVID-19? Mahasinghe pointed out that math is inevitable whenever dealing with numbers or quantities. “Aren’t we really sensitive to numbers in this COVID era more than ever? Every person is anxious to know the numbers of reported cases and deaths.” One might say the numbers are governing us because decisions are also made based on these numbers. However, these numbers are only the smoke, warns Mahasinghe. “One should be able to make a better decision if he sees the fire. Therefore, to make the best decisions during the pandemic you have to look into a mathematical model that can best describe the phenomenon.”

Numbers may govern us but what governs the numbers? According to Mahasinghe, this can only be uncovered by a model that captures the quantitative aspects of the pandemic. “It’s what we call a mathematical model which provides us with an explanation to the occurrence of these numbers.” Such a model can also forecast how these numbers are going to change in the future.

But how credible are these models? Hopefully, they are nothing like the local weather forecast. “Such models are based upon very fundamental and well-accepted laws in nature such as energy conservation, which cannot be falsified,” reiterated Mahasinghe. “Such models are supported and validated by empirical evidence. People use such models very often to make decisions in industry to make profit. So, why not look into the numbers and the math behind them to make optimal decisions accordingly, in a pandemic scenario?”

Where we went wrong

When asked where Sri Lanka went wrong in attempting to contain the pandemic, Mahasinghe said, “I guess we didn’t see the fire, we only saw the smoke. More precisely, we didn’t pay enough attention to the transmission dynamics or to optimal decision making. We were able to make some good decisions in a qualitative sense, but I seriously doubt we had the insight to make quantitatively sound decisions.” He pointed out that even when the decisions were made, the outcome could not be predicted due to a lack of a mechanism to forecast.

When asked whether the authorities were too quick to lift the lockdown, Mahasinghe answered in the negative. “I don’t think it was too early. Lifting strict lockdowns was essential at that moment. We were struggling to achieve two conflicting goals; containing the disease and sustaining the economy. Stepping down from strict curfew to partial lockdowns is indeed a good decision in such a context.” But was it methodical? Was there a mechanism to decide on the nature of the partial lockdowns? Did we know how to optimally restrict mobility in order to achieve those conflicting goals? Did we know to what extent the lockdown of a district should be optimally eased? Did we estimate the potential increase in positive cases from a district when its lockdown would be relaxed? Did we know the magnitude of the economic loss caused by shutting down a region? These are questions Marasinghe believes that authorities should have paid attention to, when easing the lockdown.

“Lockdowns could have been relaxed with the aid of proper optimization models capable of providing answers to these questions.” He repeated that such models are used very often in industrial decision making and provide promising solutions. “You can’t bring the COVID incidence down to zero even with such models, but at least you know what’s going on and the effectiveness of a decision so the health sector can take relevant measures.

According to Mahasinghe, authorities have overlooked the significance of data. “Even now I don’t think enough attention is paid to data.” According to him, some important data were not gathered. For example, he pointed out that, despite Western Province residents being advised against crossing borders, some invariably did, as there were no strict rules against it. “There is no point in regretting the fact, but we could have counted the number of vehicles that crossed the borders and used it to estimate the impact on transmission.”

He explained that the entire country can be regarded as an epidemiological network, where the nodes are the cities and the interconnections are the roads. “There are elegant models in network theory to gain many insights into transmission through such a network.” He also noted another pertinent issue, that even if data were gathered, they were not used. “Much effort was made to gather and organize COVID related data such as incidence per region etc, and that is really commendable. However, have we used them; what were the insights we gained into transmission from them except for some trivial speculations?” questions Mahasinghe. He reiterated that such insights can only be gained through an extensive study that involves the collaboration between mathematicians, computer scientists, epidemiologists and economists. “The mathematician’s part alone includes exhaustive algorithmic development and computational modelling challenges,” explained Mahasinghe.

Criteria

When asked what factors were taken into consideration in their optimization model, Mahasinghe reminded that a delicate balance must be struck between two conflicting goals. “We need to find the optimal compromise between containing the disease and sustaining the economy. As a developing country, we can’t afford beyond a certain level of the control process, so budgetary constraints must be considered.” It is obvious that COVID-19 is transmitted through human mobility. He pointed out that, consequently, inter-regional travel plays a significant role. “On the other hand, transmission dynamics can be modelled to a certain extent by well-known compartment models. However, human mobility affects the compartments and the relevant model has to be moderated accordingly to reflect that reality.” The optimization model considers all factors, such as medical capacity to deal with the pandemic, economic concerns, transmission dynamics, regional contribution to the economy, and generates a lockdown relaxation strategy that keeps the level of incidence below a desired threshold, while minimizing damage to the economy.

However, Mahasinghe pointed out that this was a prototype and it can be made closer to reality by incorporating more constraints. “For instance, I haven’t considered the fact that most agricultural activities are done in the North Central province. But, if required, that too can be incorporated without difficulty.” According to him epidemiologists and economists can introduce more constraints to the optimization model, and the applied mathematician’s job is to overcome the computational challenges posed by incorporating them.

Relevant?

There is no point in closing the stable doors after the horse has bolted. Months after the lifting of the lockdown are such models even relevant? “The compartment model that captures the transmission of COVID-19 is still applicable, irrespective of any lockdowns, unless it is quite certain that there is absolutely no community transmission. I think we were in such a stage only at the very beginning of the first wave,” said Mahasinghe. According to him, the network-based model that captures human mobility is also applicable irrespective of lockdowns or any other preventive measures. In contrast to these, the optimization model is applicable in its existing form only when lockdowns are in force. “Having said that, this model may still be useful with some changes in the present context where small regions are isolated. For instance, a slightly changed variant of that model can determine which areas should undergo isolation. Moreover, it is possible to modify the optimization model further to be used in the process of making decisions on identifying the persons to be quarantined.”

Human mobility is a critical factor in the spread of a pandemic as well as any models targeted at managing such, how could a mathematical model factor this in? “Not only COVID-19 but even dengue is transmitted mainly due to human mobility. A mosquito doesn’t travel very far during its lifetime. Humans are more responsible for carrying diseases.” Mahasinghe pointed out that COVID-19 is not very different. “If you know the way humans move from place to place, and also know the level of incidence in each place, it is not that difficult to model how the disease is transmitted through humans.” He observed that most preventive measures are also focused on restricting human mobility, which he deemed commendable. “A mathematical model can prescribe the optimal way to restrict mobility.”

What are the implications of mobility? For example are people of certain districts more inclined to travel and therefore may contribute more to the spread of the disease and are such implications reflected in the numbers? “As long as the model is deterministic and you can overcome the computational challenges by necessary algorithm development, closed-form and conclusive solutions can be generated.” Mahasinghe implied that math helps to see the big picture. “Consequences of travel from the Western to other provinces is obvious. However, considering the transport network, Southern and North Western Provinces are also at high risk.” He observed that less attention has been paid to those regions. This begs the question, are the Southern and North Western provinces a time bomb waiting to go kaboom? He reiterated that special attention must be paid to regions that are relatively less danger, such as North Central, which contributes significantly to economic growth, as the Western province is not capable of contributing to the economy in its full capacity. “It is important to keep the incidence at a low level in such places.”

The study predicted that easing lockdown in the Western Province would have adverse repercussions. “As long as vehicles cross inter-provincial barriers, the disease is transmitted to those regions. But in what magnitude? We had access to certain transport data, so we knew to a certain extent how people would mobilise within the country. Also the epidemiological data were available. So we had enough inputs to be fed into our algorithm.” The results were appalling. In fact, this computer experimentation was done in the early days when Sri Lanka was hit by the first wave and there were no strict measures to curtail inter-provincial mobility. During the days in question, Mahasinghe ranked the provinces according to their vulnerability to COVID-19, using another model, by adopting some ideas from network theory. Recently, upon perusing a map that indicated the countrywide spread of the disease Mahasinghe came to realize that the ranking has been validated, eventually. “What I don’t understand is why we failed to foresee this.”

Mahasinghe and his team had access to certain transport data, such as the number of buses, trains and bus routes. However, his models were prototypes. To make the prediction more accurate they would need current transport data, such as the number of private vehicles crossing provincial borders. “There are a number of police barriers between borders, so a vehicle count would not be impossible. If health planners are willing to use that type of model, these could be extremely valuable datasets.”

Quantifying the qualitative

In their model they quantify the degree of social distancing. But can criteria so human in nature be quantified? Moreover, how can something as complex as a pandemic, with so many variables, human in nature, be simplified into ones and zeroes? Mahasinghe maintained that it is possible to estimate the degree of social distancing observed, if provided with sufficient data. “I understand that it sounds quite unrealistic. It is because we think of individuals.” Mahasinghe emphasised the importance of noting that they are not modelling an individual, but rather a population. “Though a population consists of individuals, the dynamics of the population is not merely the sum of the dynamics of an individual. When you single out a person, the behaviour of that person is surely very uncertain and unpredictable. Take two persons, they may have certain things in common, so it is not that unpredictable. If you take a thousand people, a lot of commonalities can be extracted and the situation becomes predictable now.” He explained that, therefore, it is possible to assign a value to the degree of distancing with the aid of necessary data.

“Interestingly, it is true that we mathematicians seek certainty in an uncertain world. However, an event that looks uncertain from one point of view looks certain from another.” The toss of a coin is a simple example. “If you toss a coin, the outcome of it being head or tail is widely believed to be uncertain. However, it is the lack of data that makes it uncertain. Suppose the initial speed, the weight, the angle of projection and such were provided, then the outcome may be predictable by basic equations of motion.” Mahasinghe emphasised that math does not guarantee elimination of uncertainty. “That is definitely not the direction the mathematical sciences are moving, specially with the recent developments in quantum physics and unconventional computing. However, where macroscopic events like pandemics or human behaviour are concerned, there are many certainties that we misinterpret under the cover of uncertainty due to our lack of knowledge, eventually missing an opportunity to gain crucial insights into the scenario.”

Mahasinghe pointed out that many decisions are binary in nature. Let alone policy decisions, many behavioural decisions are inherently binary. “For instance, you may decide whether to wear a mask or not. So the one-zero nature of the action is inherent and not artificially imposed by a mathematician.” He further explained that some non-binary decisions can still be quantified. “For instance, if you decide to wear the mask on three days and go unmasked on four days of the week, it can be quantified using numbers and interpreted using probability.” Mahasinghe elaborated that, with recent developments in non deterministic models, applied mathematicians do not hesitate to incorporate uncertainty. “Consequently, uncertainty is no longer immeasurable. It is possible to confine uncertainty of the solution within reasonable limits.

What next

With all the talk on vaccination, Mahasinghe emphasised the importance of developing two mathematical models prior to vaccination. The first is a compartment model that explains the post-vaccination dynamics of the disease. “This is pretty standard in mathematical epidemiology. The second, developing a model to capture the effects of the interactions between individuals and predict the outcomes, is subtler and challenging.” He explained that once a phase of vaccination is over, persons in society can be divided into two categories: vaccinated and unvaccinated. “Take a random encounter between two persons. What type of interaction would it be? Is it a vaccinated encountering another vaccinated, an unvaccinated encountering another unvaccinated or a vaccinated encountering an unvaccinated? Obviously, the consequences of these encounters are essentially different.”

The discipline of mathematics referred to as game theory is a promising tool in modelling this type of scenario and forecasting the outcomes. In addition, once vaccination commences, there will be the issue of free riding. Due to different reasons, some people in the high risk category will also choose to remain unvaccinated, eventually resulting in a significant number of potential free riders. Mahasinghe explained that this has already been addressed in the game theory in particular, under evolutionary games. “As a nation we can’t be content with an elementary formula for herd immunity. Instead, we need to develop and upgrade elegant vaccination strategies using compartment models and game theory.” Mahasinghe is of the view that, in this pre-vaccination phase, these two are the immediate concerns that need to be addressed by applied mathematicians.

Benefits

When asked what are the drawbacks of not using a mathematical model are and the benefits of using one, Mahasinghe pointed out that in a scenario of conflicting goals and monetary restrictions, it is impossible to make decisions without seeing where the optimal compromise is. “It is easy to put the blame on politicians and other policy makers for not making the right decisions, but how can a human make an optimal decision in this entangled web of parameters, conflicting goals and constraints? Plainly speaking, we need computers to generate the best decisions for us.” That’s indeed what the computers are intended to do primarily, according to Mahasinghe, although they are more frequently used to watch YouTube videos and log into Facebook!

But to perform the intended task using a computer, models and algorithms that can be read by the computer must be created. “That’s why you need to look into optimization, mathematical programming, computational modelling and game theory. This way, you may be able to keep the numbers within certain limits. Also, you can pre-assess a decision quantitatively. Our health workers and armed forces have already committed much and continue to do so and to receive the full benefit of their commitments, the willingness to switch from qualitative to quantitative methods, is essential.

When asked if such models are used successfully in other countries to counter the pandemic, Mahasinghe answered in the affirmative. Since the very beginning, an extensive mathematical modelling process has been done and that’s how the predictions were made. In fact, vaccination models had long been applied to control epidemics even in African countries. In Sri Lanka, there are many misconceptions about mathematical models.” Mahasinghe has observed certain non-mathematicians presenting elementary regressions, numerical approximations and statistical tests, erroneously referring to them as mathematical models.

“Perhaps that’s why some policy makers have lost faith in math. As mentioned earlier, a mathematical model is based on an unfalsifiable conservation law. It cannot be compared to a trivial curve fitting cakewalk. Our people get easily carried away by exotic words. People tend to admire words like machine learning, artificial intelligence and such, but how many are aware of the maths behind these words?” He observed that a closer examination of news reports on machine learning or AI being used in some country to counter the pandemic, would reveal that they are mathematical models and machine learning techniques are used due to the toughness of generating a closed-form solution. “Even to apply computational heuristics, the problem has to be formulated mathematically. Correct problem formulation is a major component of a so-called AI-powered decision.

Mahasinghe explained that the subject of operations research emerged in the new industrial era to enable industrial decision making using computers, as the number of industrial parameters exceeded human ability to process. “The pandemic has now reached this level so that no human can make an optimal decision without the aid of a computer. Therefore, we need to start working on quantitative models to identify optimal decisions, instead of pointing fingers for not making proper decisions, when decision making is literally beyond the capacity of a human.”

Features

A wage for housework? India’s sweeping experiment in paying women

In a village in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh, a woman receives a small but steady sum each month – not wages, for she has no formal job, but an unconditional cash transfer from the government.

Premila Bhalavi says the money covers medicines, vegetables and her son’s school fees. The sum, 1,500 rupees ($16: £12), may be small, but its effect – predictable income, a sense of control and a taste of independence – is anything but.

Her story is increasingly common. Across India, 118 million adult women in 12 states now receive unconditional cash transfers from their governments, making India the site of one of the world’s largest and least-studied social-policy experiments.

Long accustomed to subsidising grain, fuel and rural jobs, India has stumbled into something more radical: paying adult women simply because they keep households running, bear the burden of unpaid care and form an electorate too large to ignore.

Eligibility filters vary – age thresholds, income caps and exclusions for families with government employees, taxpayers or owners of cars or large plots of land.

“The unconditional cash transfers signal a significant expansion of Indian states’ welfare regimes in favour of women,” Prabha Kotiswaran, a professor of law and social justice at King’s College London, told the BBC.

The transfers range from 1,000-2,500 rupees ($12-$30) a month – meagre sums, worth roughly 5-12% of household income, but regular. With 300 million women now holding bank accounts, transfers have become administratively simple.

Women typically spend the money on household and family needs – children’s education, groceries, cooking gas, medical and emergency expenses, retiring small debts and occasional personal items like gold or small comforts.

What sets India apart from Mexico, Brazil or Indonesia – countries with large conditional cash-transfer schemes – is the absence of conditions: the money arrives whether or not a child attends school or a household falls below the poverty line.

Goa was the first state to launch an unconditional cash transfer scheme to women in 2013. The phenomenon picked up just before the pandemic in 2020, when north-eastern Assam rolled out a scheme for vulnerable women. Since then these transfers have turned into a political juggernaut.

The recent wave of unconditional cash transfers targets adult women, with some states acknowledging their unpaid domestic and care work. Tamil Nadu frames its payments as a “rights grant” while West Bengal’s scheme similarly recognises women’s unpaid contributions.

In other states, the recognition is implicit: policymakers expect women to use the transfers for household and family welfare, say experts.

This focus on women’s economic role has also shaped politics: in 2021, Tamil actor-turned-politician Kamal Haasan promised “salaries for housewives”. (His fledgling party lost.) By 2024, pledges of women-focused cash transfers helped deliver victories to political parties in Maharashtra, Jharkhand, Odisha, Haryana and Andhra Pradesh.

In the recent elections in Bihar, the political power of cash transfers was on stark display. In the weeks before polling in the country’s poorest state, the government transferred 10,000 rupees ($112; £85) to 7.5 million female bank accounts under a livelihood-generation scheme. Women voted in larger numbers than men, decisively shaping the outcome.

Critics called it blatant vote-buying, but the result was clear: women helped the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led coalition secure a landslide victory. Many believe this cash infusion was a reminder of how financial support can be used as political leverage.

Yet Bihar is only one piece of a much larger picture. Across India, unconditional cash transfers are reaching tens of millions of women on a regular basis.

Maharashtra alone promises benefits for 25 million women; Odisha’s scheme reaches 71% of its female voters.

In some policy circles, the schemes are derided as vote-buying freebies. They also put pressure on state finances: 12 states are set to spend around $18bn on such payouts this fiscal year. A report by think-tank PRS Legislative Research notes that half of these states face revenue deficits – this happens when a state borrows to pay regular expenses without creating assets.

But many argue they also reflect a slow recognition of something India’s feminists have argued for decades: the economic value of unpaid domestic and care work.

Women in India spent nearly five hours a day on such work in 2024 – more than three times the time spent by men, according to the latest Time Use Survey. This lopsided burden helps explain India’s stubbornly low female labour-force participation. The cash transfers, at least, acknowledge the imbalance, experts say.

Do they work?

Evidence is still thin but instructive. A 2025 study in Maharashtra found that 30% of eligible women did not register – sometimes because of documentation problems, sometimes out of a sense of self-sufficiency. But among those who did, nearly all controlled their own bank accounts.

A 2023 survey in West Bengal found that 90% operated their accounts themselves and 86% decided how to spend the money. Most used it for food, education and medical costs; hardly transformative, but the regularity offered security and a sense of agency.

More detailed work by Prof Kotiswaran and colleagues shows mixed outcomes.

In Assam, most women spent the money on essentials; many appreciated the dignity it afforded, but few linked it to recognition of unpaid work, and most would still prefer paid jobs.

In Tamil Nadu, women getting the money spoke of peace of mind, reduced marital conflict and newfound confidence – a rare social dividend. In Karnataka, beneficiaries reported eating better, gaining more say in household decisions and wanting higher payments.

Yet only a sliver understood the scheme as compensation for unpaid care work; messaging had not travelled. Even so, women said the money allowed them to question politicians and manage emergencies. Across studies, the majority of women had full control of the cash.

“The evidence shows that the cash transfers are tremendously useful for women to meet their own immediate needs and those of their households. They also restore dignity to women who are otherwise financially dependent on their husbands for every minor expense,” Prof Kotiswaran says.

Importantly, none of the surveys finds evidence that the money discourages women from seeking paid work or entrench gender roles – the two big feminist fears, according to a report by Prof Kotiswaran along with Gale Andrew and Madhusree Jana.

Nor have they reduced women’s unpaid workload, the researchers find. They do, however, strengthen financial autonomy and modestly strengthen bargaining power. They are neither panacea nor poison: they are useful but limited tools, operating in a patriarchal society where cash alone cannot undo structural inequities.

What next?

The emerging research offers clear hints.

Eligibility rules should be simplified, especially for women doing heavy unpaid care work. Transfers should remain unconditional and independent of marital status.

But messaging should emphasise women’s rights and the value of unpaid work, and financial-literacy efforts must deepen, researchers say. And cash transfers cannot substitute for employment opportunities; many women say what they really want is work that pays and respect that endures.

“If the transfers are coupled with messaging on the recognition of women’s unpaid work, they could potentially disrupt the gendered division of labour when paid employment opportunities become available,” says Prof Kotiswaran.

India’s quiet cash transfers revolution is still in its early chapters. But it already shows that small, regular sums – paid directly to women – can shift power in subtle, significant ways.

Whether this becomes a path to empowerment or merely a new form of political patronage will depend on what India chooses to build around the money.

[BBC]

Features

People set example for politicians to follow

Some opposition political parties have striven hard to turn the disaster of Cyclone Ditwah to their advantage. A calamity of such unanticipated proportions ought to have enabled all political parties to come together to deal with this tragedy. Failure to do so would indicate both political and moral bankruptcy. The main issue they have forcefully brought up is the government’s failure to take early action on the Meteorological Department’s warnings. The Opposition even convened a meeting of their own with former President Ranil Wickremesinghe and other senior politicians who shared their experience of dealing with natural and man-made disasters of the past, and the present government’s failures to match them.

The difficulty to anticipate the havoc caused by the cyclone was compounded by the neglect of the disaster management system, which includes previous governments that failed to utilise the allocated funds in an open, transparent and corruption free manner. Land designated as “Red Zones” by the National Building Research Organisation (NBRO), a government research and development institute, were built upon by people and ignored by successive governments, civil society and the media alike. NBRO was established in 1984. According to NBRO records, the decision to launch a formal “Landslide Hazard Zonation Mapping Project (LHMP)” dates from 1986. The institutional process of identifying landslide-prone slopes, classifying zones (including what we today call “Red Zones”), and producing hazard maps, started roughly 35 to 40 years ago.

Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines which were lashed by cyclones at around the same time as Sri Lanka experienced Cyclone Ditwah were also unprepared and also suffered enormously. The devastation caused by cyclones in the larger southeast Asian region is due to global climate change. During Cyclone Ditwah some parts of the central highlands received more than 500 mm of rainfall. Official climatological data cite the average annual rainfall for Sri Lanka as roughly 1850 mm though this varies widely by region: from around 900 mm in the dry zones up to 5,000 mm in wet zones. The torrential rains triggered by Ditwah were so heavy that for some communities they represented a rainfall surge comparable to a major part of their typical annual rainfall.

Inclusive Approach

Climate change now joins the pantheon of Sri Lanka’s challenges that are beyond the ability of a single political party or government to resolve. It is like the economic bankruptcy, ethnic conflict and corruption in governance that requires an inclusive approach in which the Opposition, civil society, religious society and the business community need to join rather than merely criticise the government. It will be in their self-interest to do so. A younger generation (Gen Z), with more energy and familiarity with digital technologies filled, the gaps that the government was unable to fill and, in a sense, made both the Opposition and traditional civil society redundant.

Within hours of news coming in that floods and landslides were causing havoc to hundreds of thousands of people, a people’s movement for relief measures was underway. There was no one organiser or leader. There were hundreds who catalysed volunteers to mobilise to collect resources and to cook meals for the victims in community kitchens they set up. These community kitchens sprang up in schools, temples, mosques, garages and even roadside stalls. Volunteers used social media to crowdsource supplies, match donors with delivery vehicles, and coordinate routes that had become impassable due to fallen trees or mudslides. It was a level of commitment and coordination rarely achieved by formal institutions.

The spontaneous outpouring of support was not only a youth phenomenon. The larger population, too, contributed to the relief effort. The Galle District Secretariat sent 23 tons of rice to the cyclone affected areas from donations brought by the people. The Matara District Secretariat made arrangements to send teams of volunteers to the worst affected areas. Just as in the Aragalaya protest movement of 2022, those who joined the relief effort were from all ethnic and religious communities. They gave their assistance to anyone in need, regardless of community. This showed that in times of crisis, Sri Lankans treat others without discrimination as human beings, not as members of specific communities.

Turning Point

The challenge to the government will be to ensure that the unity among the people that the cyclone disaster has brought will outlive the immediate relief phase and continue into the longer term task of national reconstruction. There will be a need to rethink the course of economic development to ensure human security. President Anura Kumara Dissanayake has spoken about the need to resettle all people who live above 5000 feet and to reforest those areas. This will require finding land for resettlement elsewhere. The resettlement of people in the hill country will require that the government address the issue of land rights for the Malaiyaha Tamils.

Since independence the Malaiyaha Tamils have been collectively denied ownership to land due first to citizenship issues and now due to poverty and unwillingness of plantation managements to deal with these issues in a just and humanitarian manner beneficial to the workers. Their resettlement raises complex social, economic and political questions. It demands careful planning to avoid repeating past mistakes where displaced communities were moved to areas lacking water, infrastructure or livelihoods. It also requires political consensus, as land is one of the most contentious issues in Sri Lanka, tied closely to identity, ethnicity and historical grievances. Any sustainable solution must go beyond temporary relocation and confront the historical exclusion of the Malaiyaha Tamil community, whose labour sustains the plantation economy but who remain among the poorest groups in the country.

Cyclone Ditwah has thus become a turning point. It has highlighted the need to strengthen governance and disaster preparedness, but it has also revealed a different possibility for Sri Lanka, one in which the people lead with humanity and aspire for the wellbeing of all, and the political leadership emulates their example. The people have shown through their collective response to Cyclone Ditwah that unity and compassion remain strong, which a sincere, moral and hardworking government can tap into. The challenge to the government will be to ensure that the unity among the people that the cyclone disaster has brought will outlive the immediate relief phase and continue into the longer term task of national reconstruction with political reconciliation.

by Jehan Perera

Features

An awakening: Revisiting education policy after Cyclone Ditwah

In the short span of two or three days, Cyclone Ditwah, has caused a disaster of unprecedented proportions in our midst. Lashing away at almost the entirety of the country, it has broken through the ramparts of centuries old structures and eroded into areas, once considered safe and secure.

In the short span of two or three days, Cyclone Ditwah, has caused a disaster of unprecedented proportions in our midst. Lashing away at almost the entirety of the country, it has broken through the ramparts of centuries old structures and eroded into areas, once considered safe and secure.

The rains may have passed us by. The waters will recede, shops will reopen, water will be in our taps, and we can resume the daily grind of life. But it will not be the same anymore; it should not be. It should not be business as usual for any of us, nor for the government. Within the past few years, Sri Lankan communities have found themselves in the middle of a crisis after crisis, both natural and man-made, but always made acute by the myopic policies of successive governments, and fuelled by the deeply hierarchical, gendered and ethnicised divides that exist within our societies. The need of the hour for the government today is to reassess its policies and rethink the directions the country, as a whole, has been pushed into.

Neoliberal disaster

In the aftermath of the devastation caused by the natural disaster, fundamental questions have been raised about our existence. Our disaster is, in whole or in part, the result of a badly and cruelly managed environment of the planet. Questions have been raised about the nature of our economy. We need to rethink the way land is used. Livelihoods may have to be built anew, promoting people’s welfare, and by deveoloping a policy on climate change. Mega construction projects is a major culprit as commentators have noted. Landslides in the upcountry are not merely a result of Ditwah lashing at our shores and hills, but are far more structural and points to centuries of mismanagement of land. (https://island.lk/weather-disasters-sri-lanka-flooded-by-policy-blunders-weak-enforcement-and-environmental-crime-climate-expert/). It is also about the way people have been shunted into lands, voluntarily or involuntarily, that are precarious, in their pursuit of a viable livelihood, within the limited opportunities available to them.

Neo liberal policies that demand unfettered land appropriation and built on the premise of economic growth at any expense, leading to growing rural-urban divides, need to be scrutinised for their short and long term consequences. And it is not that any of these economic drives have brought any measure of relief and rejuvenation of the economy. We have been under the tyrannical hold of the IMF, camouflaged as aid and recovery, but sinking us deeper into the debt trap. In October 2025, Ahilan Kadirgamar writes, that the IMF programme by the end of 2027, “will set up Sri Lanka for the next crisis.” He also lambasts the Central Bank and the government’s fiscal policy for their punishing interest rates in the context of disinflation and rising poverty levels. We have had to devalue the rupee last month, and continue to rely on the workforce of domestic workers in West Asia as the major source of foreign exchange. The government’s negotiations with the IMF have focused largely on relief and infrastructure rebuilding, despite calls from civil society, demanding debt justice.

The government has unabashedly repledged its support for the big business class. The cruelest cut of them all is the appointment of a set of high level corporate personalities to the post-disaster recovery committee, with the grand name, “Rebuilding Sri Lanka.” The message is loud and clear, and is clearly a slap in the face of the working people of the country, whose needs run counter to the excessive greed of extractive corporate freeloaders. Economic growth has to be understood in terms that are radically different from what we have been forced to think of it as, till now. For instance, instead of investment for high profits, and the business of buy and sell in the market, rechannel investment and labour into overall welfare. Even catch phrases like sustainable development have missed their mark. We need to think of the economy more holistically and see it as the sustainability of life, livelihood and the wellbeing of the planet.

The disaster has brought on an urgency for rethinking our policies. One of the areas where this is critical is education. There are two fundamental challenges facing education: Budget allocation and priorities. In an address at a gathering of the Chamber of Commerce, on 02 December, speaking on rebuilding efforts, the Prime Minister and Minister of Education Dr. Harini Amarasuriya restated her commitment to the budget that has been passed, a budget that has a meagre 2.4% of the GDP allocated for education. This allocation for education comes in a year that educational reforms are being rolled out, when heavy expenses will likely be incurred. In the aftermath of the disaster, this has become more urgent than ever.

Reforms in Education

The Government has announced a set of amendments to educational policy and implementation, with little warning and almost no consultation with the public, found in the document, Transforming General Education in Sri Lanka 2025 published by the Ministry of Education. Though hailed as transformative by the Prime Minister (https://www.news.lk/current-affairs/in-the-prevailing-situation-it-is-necessary-to-act-strategically-while-creating-the-proper-investments-ensuring-that-actions-are-discharged-on-proper-policies-pm), the policy is no more than a regurgitation of what is already there, made worse. There are a few welcome moves, like the importance placed on vocational training. Here, I want to raise three points relating to vital areas of the curriculum that are of concern: 1) streamlining at an early age; relatedly 2) prioritising and privileging what is seen as STEM education; and 3) introducing a credit-based modular education.

1. A study of the policy document will demonstrate very clearly that streamlining begins with Junior Secondary Education via a career interest test, that encourages students to pursue a particular stream in higher studies. Further Learning Modules at both “Junior Secondary Education” and “Senior Secondary Education Phase I,” entrench this tendency. Psychometric testing, that furthers this goal, as already written about in our column (https://kuppicollective.lk/psychometrics-and-the-curriculum-for-general-education/) points to the bizarre.

2. The kernel of the curriculum of the qualifying examination of Senior Secondary Education Phase I, has five mandatory subjects, including First Language, Math, and Science. There is no mandatory social science or humanities related subject. One can choose two subjects from a set of electives that has history and geography as separate subjects, but a Humanities/Social Science subject is not in the list of mandatory subjects. .

3. A credit-based, modular education: Even in universities, at the level of an advanced study of a discipline, many of us are struggling with module-based education. The credit system promotes a fragmented learning process, where, depth is sacrificed for quick learning, evaluated numerically, in credit values.

Units of learning, assessed, piece meal, are emphasised over fundamentals and the detailing of fundamentals. Introducing a module based curriculum in secondary education can have an adverse impact on developing the capacity of a student to learn a subject in a sustained manner at deeper levels.

Education wise, and pedagogically, we need to be concerned about rigidly compartmentalising science oriented, including technological subjects, separately from Humanities and Social Studies. This cleavage is what has led to the idea of calling science related subjects, STEM, automatically devaluing humanities and social sciences. Ironically, universities, today, have attempted, in some instances, to mix both streams in their curriculums, but with little success; for the overall paradigm of education has been less about educational goals and pedagogical imperatives, than about technocratic priorities, namely, compartmentalisation, fragmentation, and piecemeal consumerism. A holistic response to development needs to rethink such priorities, categorisations and specialisations. A social and sociological approach has to be built into all our educational and development programmes.

National Disasters and Rebuilding Community

In the aftermath of the disaster, the role of education has to be rethought radically. We need a curriculum that is not trapped in the dichotomy of STEM and Humanities, and be overly streamlined and fragmented. The introduction of climate change as a discipline, or attention to environmental destruction cannot be a STEM subject, a Social Science/Humanities subject or even a blend of the two. It is about the vision of an economic-cum-educational policy that sees the environment and the economy as a function of the welfare of the people. Educational reforms must be built on those fundamentals and not on real or imagined short term goals, promoted at the economic end by neo liberal policies and the profiteering capitalist class.

As I write this, the sky brightens with its first streaks of light, after days of incessant rain and gloom, bringing hope into our hearts, and some cheer into the hearts of those hundreds of thousands of massively affected people, anxiously waiting for a change in the weather every second of their lives. The sense of hope that allows us to forge ahead is collective and social. The response by Lankan communities, to the disaster, has been tremendously heartwarming, infusing hope into what still is a situation without hope for many. This spirit of collective endeavour holds the promise for what should be the foundation for recovery. People’s demands and needs should shape the re-envisioning of policy, particularly in the vital areas of education and economy.

(Sivamohan Sumathy was formerly attached to the Department of English, University of Peradeniya)

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.

By Sivamohan Sumathy

-

News6 days ago

Lunuwila tragedy not caused by those videoing Bell 212: SLAF

-

News1 day ago

News1 day agoOver 35,000 drug offenders nabbed in 36 days

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoLevel III landslide early warning continue to be in force in the districts of Kandy, Kegalle, Kurunegala and Matale

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoLOLC Finance Factoring powers business growth

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoCPC delegation meets JVP for talks on disaster response

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoA 6th Year Accolade: The Eternal Opulence of My Fair Lady

-

News1 day ago

News1 day agoRising water level in Malwathu Oya triggers alert in Thanthirimale

-

Midweek Review6 days ago

Midweek Review6 days agoHouse erupts over Met Chief’s 12 Nov unheeded warning about cyclone Ditwah